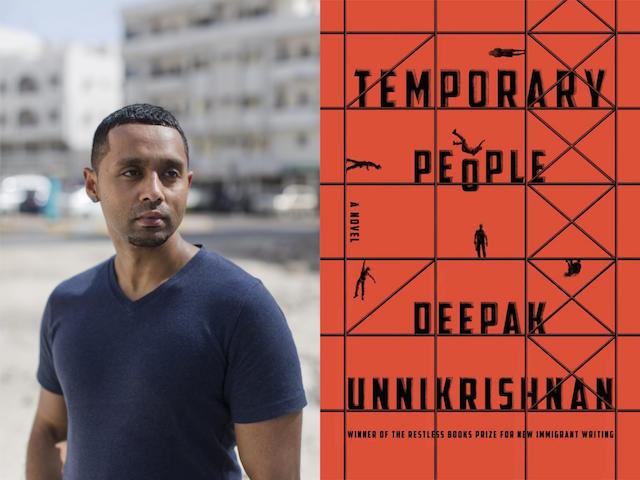

“When people ask me how much of the book is autobiographical, I often tell them, ‘Well, you know the story where the man turns into a suitcase? That’s my uncle.'”

October 31, 2018

Deepak Unnikrishnan’s novel Temporary People, winner of the inaugural Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing in 2016 and most recently longlisted for this year’s DSC Prize in South Asian Literature, is by turns fabulist and lyrical, crackling with the voices of migrant workers in the UAE who represent more than 80 percent of the population yet are eventually required to leave. How this temporary status affects the psyche, the memories and language of the pravasi—Malayalam for someone who lives away from their homeland—beats at the heart of Unnikrishnan’s wildly inventive stories where workers fall from construction site towers and are repaired with tape; siblings in the Gulf bicker over what to do with an unwanted dog left guarding their dead mother’s empty house in Kerala; an overzealous TSA agent conducting a cavity search ends up lodged in a passenger’s ass.

In The Migrant as Writer, Ha Jin writes, “Just as a creative writer should aspire to be not a broker but a creator of culture, a great novel does not only present a culture but also makes culture.” This is the thrill one gets from reading Unnikrishnan—of feeling in the hands of a writer who is making culture with all its joy and brutality. His writing gives me courage. This interview took place by phone last year and has been condensed for length.

—Lisa Chen

Lisa Chen: Temporary People has been described as a kaleidoscopic, polyphonic, a “bottom-up vernacular history of the modern Gulf oil state.” An enormous part of its power comes from its mongrel, kinetic form. Can you say more about its evolution?

Deepak Unnikrishnan: I wish I could tell you it was all intuition and something quite profound, but here’s the truth: I left Abu Dhabi in 2001 and I landed in Jersey. The timing was two weeks before 9/11. I wasn’t missing home at all simply because I didn’t know what that would feel like. But a couple years into it, I couldn’t go home because I couldn’t afford the ticket. So I spent five years away from home, not seeing family. I guess it hit me harder than I thought it would. For the first time in my life, I really understood what my parents had to deal with—they left their own families to raise us. I started thinking what it meant to be from the Gulf or Al Khaleej, as we call it in Arabic. I wanted to find out what type of narrative about the place was out there, but I didn’t find much in English. That was disconcerting because I thought I wasn’t looking hard enough, or I wasn’t sure where to look. So I started penning down these “vignettes of angst.”

Around this time, I stumbled across a piece, “The Dark Side of the Dubai” by Johann Hari in The Independent. I remember, going, “Ah ha, this is right.” I had been away from home so long that I was thankful and grateful that someone had written about Dubai. But when I returned to the piece two to three months later, I thought the gentleman was just mad! He didn’t document anything I knew. Over time, I’ve seen other things in reports that represented the Gulf as something that [the authors] could absolutely “get”: they knew exactly what it was—the glitz and the glamour, the fast cars, the oil money. Around 2010, Dubai became a brand that stood for everything else—Abu Dhabi, Doha; it basically stood for opulence. I couldn’t figure out why when folks were writing about people who look like my parents, they were getting written about in a certain way, almost like they were caricatures. I wanted to try to fix that.

I started reading and returning to people I admired like Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee. I realized I was trying to do something, but I didn’t know what that something was. Probably in 2012, I realized what I really want to do: I wanted to play with language. When I say “language,” I don’t mean English, I’m talking about everything—how language gets used in this city. I wanted someone to read the book and not know what to make of it. Because when a book comes from a place like UAE, there are expectations that the reader has, especially if they haven’t been here. Expectations of what the place and the city are like. What doesn’t get talked about as much, and it’s a shame, is the kind of artist that gets produced in a city like Abu Dhabi.

To be honest, I didn’t even know what “form” meant. Beth Nugent, one of my teachers, said, “Why are you playing with form?” I said, “I’m sorry, you might have to define what ‘form’ means because I don’t know what you’re talking about.” She said that I was toying with narrative structure. I never thought that was the case, because to me it felt normal. I’m from Abu Dhabi but I’m also attached to cities like New York and Chicago. That was freeing, too, simply because I realized I’m just going to write this for me, as a document for my family so I can understand what I’ve become.

Apart from language, what were important influences or building blocks as you were constructing the book?

When you think about how stories get told, I did think of my own family. When my great-grandma recited stories to me, I thought, “How do I put it on the page?” I started thinking about rhythm. The text needed musicality. At the same time, I wanted readers to understand that the stories needed each other—they needed to talk with each other. I could make the case for a piece to be in the book that was technically flawed but that would be of value to the book if the others pieces propped it up. I started seeing and envisioning the book that way.

When I’m asked, “Who are your influences?” I often mention standup. People like George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Mitch Hedberg. People are sometimes surprised by that. But If you look at Carlin, it’s about language; if you follow Pryor it’s about rhythm. Mitch Hedberg, he could give most surrealists nightmares because of what he can do with imagery—I wanted all of that. I wanted the work to sort of dance. Have you seen Wim Wender’s Pina? It’s a documentary about Pina Bausch. You know the opening sequence when a woman comes out and plays an accordion and lists the seasons—spring, winter—and her entire body tells you what each season is supposed to look like? I remember seeing that and thinking, I want my work to do that.

Colson Whitehead once wrote a tongue-in-cheek essay about avoiding certain tropes in fiction, i.e., the “Southern Novel of Black Misery.” When I read Underground Railroad I found myself thinking of the book he was writing against as much as the one he wrote. I’m curious whether when you set out to write Temporary People, if there was a shadow book or certain conventions that you were conscious not to engage?

One thing I didn’t want was for people to look at the book, and go, “Finally someone has written a manual about Abu Dhabi.” Or “I need a book about Dubai,” and have someone respond, “You should read Unnikrishnan.” In his New Yorker piece Peter Baker mentions he was looking for a certain book or books that could push up against what he was reading about [the Gulf]: most of what’s out there is reportage by western reporters. A lot of the reporting is crucial, especially when it’s about labor. But there’s also a certain type of arrogance and dismissal of art, of the brown laborer who is supposed to behave a certain way. I want someone to pick up the work and have questions and return to it periodically and figure out what the writer is trying to say. Because the book is also about me trying to figure things out. It’s not a book that has answers but rather certain questions that the writer has been grappling with.

I remember reading Coetzee’s Disgrace… the fact that he could love a place so much and critique it and at the same time hold it and try to figure it out. Then I would read the essays of [V.S.] Naipaul and think, “How can someone be so brutally candid about a place?” He has received a lot of criticism for certain things he’s said but I have always admired the courage to write that down. I wanted that.

There is one essay that really helped that I came across it as I was finishing the book: James Woods’ “On Not Going Home. There’s a word in there, “homelooseness.” I read that and thought, Oh my god, that’s my word. He stole my word! That’s a state I understand: Not only do you feel detached, but you feel attached at the same time. I want you to hear the city rather than figure out what the city means. I think that’s as useful if not more important… When I’m speaking in Malayalam, my syntax is sometimes in English. English is how I think, but Malayalam is what I need to speak to my family. That is the city to me. I wanted to write a book that not only spoke about they city I knew but paid homage to the language.

This is going to sound weird, but I was delighted by the lack of nobility in your book. Like the characters in Paul Beatty’s novels or in the Coen brothers’ movies, people act cruelly, carelessly; they masturbate, they are petulant, profane. Everyone is a hustler. And there is enormous complexity and humanity in the hustle.

It’s really fascinating that you mention the Coen bothers. I adore them. No one’s perfect—that [idea] was really important to me. I’d read narratives where the laborer was a hapless person to be pitied. No: they can be human beings. They have good days and bad days. The stories have bits of humor and bits of pain and bits of joy. Even though the context might be considered surreal or violent, I still wanted people to talk each other. When we were little, our parents wanted us to avoid confrontation, to be invisible. The book is about confrontation and also about communication. [The characters] deal with confrontation by talking.

James Joyce’s Dubliners and Naipaul’s Miguel Street are backward reflections of a place in time; the narrator comes of age and leaves the city of his youth behind. But unlike those narratives, you seem to have made a conscious decision to not feature a central narrator, with the possible exception of the unnamed “Boy” in the story “Blatella Germanica,” which manages to evoke The Metamorphosis, Animal Farm and Planet of the Apes, who turns up as an adult in the U.S. later in the book, and who may or may not appear later as the narrator elsewhere. Why resist deploying a central narrator throughout?

I’m glad you picked up on that. Names are very important to me. But we’re also talking about a city and country where people are always in flux. They’re transient members of the community. They’re not here for long, but “long” is relative. My parents have been here for 40 years, but the minute they have to leave—when they’re required to leave—40 years won’t seem that like much.

What do I do with the characters so you understand that they’ll stick around for a while and then disappear, but possibly reappear? I wanted you to figure out for yourself if it’s the same person. A case could be made that multiple characters reappear, but in different forms. That was something I wanted to play with. On top of that, the work is called “temporary people,” [foreign nationals] are not allowed time to linger long enough to invite you into their home and, you know, offer you dinner and beer. There’s just enough time to have that conversation on a commute if you’re sitting next someone and they’re telling you stories. And then they’re gone. The story “Taxi Man” is just a conversation with a taxi driver.

If there’s one refrain in the book it’s pravasi. It’s a representation of all the people who populate the book. The other constant is language. Because people use language a certain way not to just document their stories, but it’s their method of implanting themselves in the city after they leave it. It is purposeful. It’s also me trying to remind the reader that it is incredibly hard to pin this place down, especially when most of the narratives and reportage about it tell you what the place is—it’s labor, it’s flashy cars, it’s oil money; there’s no maneuverability. The book, because of it does what it does with the stories and the form, is trying to remind the reader and the writer that no one is really sure how to define this place.

In your story, “Kloon,” a young foreign national burdened with student debt takes a job that involves wearing a clown costume and carrying a dirty clown doll while shilling laundry detergent in front of supermarkets. The story is scathing but also quite funny, with an unpredictable twist in the end where the power dynamics are shifted, as they so often are in your stories. Reading “Kloon,” I was reminded of the Liberty Paints sequence in Ellison’s Invisible Man. Can you say more about your use of allegory, especially about a place that is already steeped in so much contemporary myth-making?

Part of it was I was writing from the point of view of an insider. At least that’s what I thought I was, even though I was writing it away from home. Since I’ve been back in the country, I’ve thought, “I got that wrong, okay, I got that wrong, too” [laughs]. That’s where the myth-making and allegory really help. That’s the main reason why I play with allegory and surrealism because when you’re away and you have that distance, it’s as though you have more access to the place, but you’re not really sure what it is you have access to. And that has always interested me because you know, my parents did that, they talked of India: “India’s like this and India’s like that.” And we studied India in high school; I went to an Indian school in Abu Dhabi and it doesn’t get more Indian than that! But when we would go [to India], some things didn’t make sense because my family was operating in a past that didn’t exist and my school was operating in a past that was fed to us.

When I was writing about the place, I was also reading [George] Saunders, thinking, “Man, the guy can do things with mythology and myth-making, and world-building and I want to do something like that.” I did not want to write a book that was too real so people assume that, “Ah, this is what the place is, this is what it’s supposed to be, finally, we have someone telling us.” So I started playing with mythology. But at the same time I was just borrowing from what I knew. Grandma recited tales to me, so I used that. But to be really simple about my answer, there is a lot of mythology and world-making because it’s tons of fucking fun. It brought me joy, so that’s why I wrote it.

At a talk you gave at NYU once, you said that, as a writer, you worry about “fetishizing everything,” turning the private moments of your parents into myth for us, the readers. Mary Gaitskill’s The Mare is about a white woman who sponsors a Dominican girl as part of an outdoor program for low-income teens. At one point the girl’s six-year-old brother calls the woman a “nonfiction bitch,” which struck me as a brilliant, uncanny intuition about the narrative that was being constructed around and about them, and the woman’s complicity in it. How do we avoid being nonfiction bitches? What advice would you give to a writer grappling with the issue you described?

It’s funny, I remember watching a stand-up special of Russell Peters’ on the telly. He has this bit about his dad; the punchline is something like, “Someone’s gonna get hurt, real bad.” It’s a very famous line he kept using in his standup. He retired the line after he lost his dad. The explanation he gave was that it didn’t make sense anymore because his dad wasn’t there. I thought that was really interesting. I do write about families and communities, and sometimes I wonder why. I want to document my family because I know they will leave [Abu Dhabi] someday and I won’t be here either, simply because of the way things are run here.

At the same time when I was writing the book, I was wondering, how do I protect them? I knew I’d get questions about them. What I do is, when I give readings, whatever I say about my parents is fine as long I say it. But if I get asked questions about them and I don’t wish to answer them to protect their privacy, I say that; I’m not going to go there.

It’s funny you mention Gaitskill because I remember reading Bad Behavior and thinking, my god, this woman can really write, and she can really write about sex! But if you have a writer of color doing that, especially who grew up in the region where I grew up, there’s the possibility that the reader could read something I wrote, and go, “My god, the book is about sexual rage and repression and oppression—what a brave thing to do!” But at the end of the day, it’s just sex, it’s just frustration–it could be an angry young man anywhere just raging, that’s it, nothing more than that. Or it could be more than that, and that’s okay.

I don’t think [writers of color] have the liberty or privilege to just write. We always represent something. We even have a special section in bookstores! People will tell you Saunders is an American writer but you don’t dig into his background. But with writers of color, you know everything—you know what that the uncle is called, and you know who the aunt is married to [laughs]. In that sense, you feel exposed, because everything seems to matter.

When people ask me how much of the book is autobiographical, I often tell them, “Well, you know the story where the man turns into a suitcase? That’s my uncle.” Sometimes what happens is we put so much pressure on ourselves as writers of color to represent, that we forget to chill and breathe and have fun, and say, “Hey man, I have no idea what I’m representing at the moment. But here’s what I think I am.”

That changes for me when people are being bullied, and that is the age we’re living in now. Bullied because of paperwork, bullied because of what they look like, bullied because of who they pray to. Then you get a sense that, there are certain things you need to say; if you don’t say them, people think you are not affected, and that you don’t care. There I draw the line. If people are interested in the book because of my background, I can’t deny that. But because that has given me access, or an “in,” I’m going to try to do my best to dispel certain myths, so when you read another writer from the region, you won’t know what to expect. That’s important to me.