“I think that sensual pleasure is at the heart of what I find to be exciting about writing.”

September 16, 2020

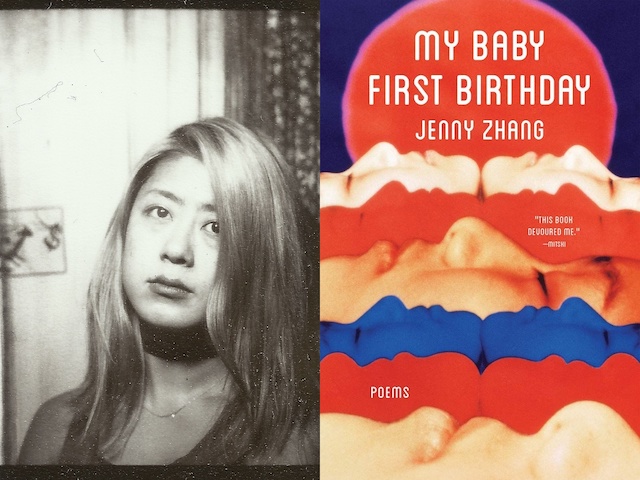

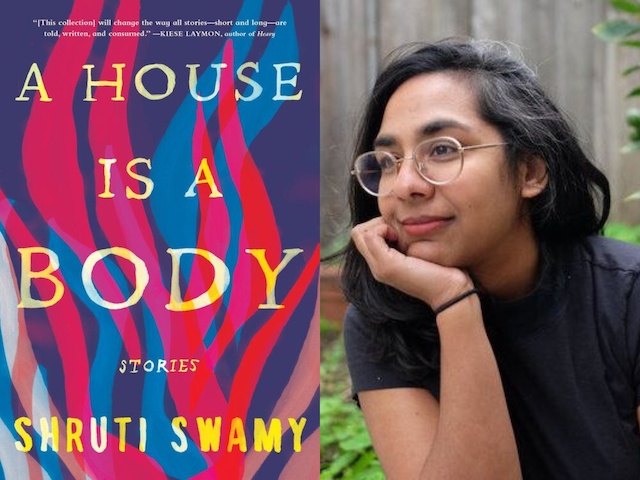

Dreams are the language for desire in A House is a Body, Shruti Swamy’s debut collection, out this fall from Algonquin Books. In these twelve stories, brown women dream of the earthly and alien, of gods and lovers, and of past lives and possible futures. These dreams are more than a narrative mode—they’re a formal choice, the refusal of a conventional opinion that dreams in fiction are easy shortcuts into a character’s id. Swamy is such a graceful stylist that her stories shifts into the unreal are sustained by her poise as a writer. Often, these shifts are into a heightened experience of reality, which, in these stories, is permeated with sensual pleasure and the proximity of death. Take the opening lines of the titular story in which a woman wakes to a forest fire nearing her home (a story that is particularly relevant as fires burn across the West Coast): “Not the scent of the smoke, but the sight of it, not the sight itself, but the screen through which it altered the sunlight—she couldn’t articulate the change exactly, it’s just that the light seemed odd, like the sour light of a nightmare.”

Swamy’s stories follow Indian women in India and the United States, forming an expansive world unto itself. In one story, a woman watches her dog engage in a life-or-death struggle with a cobra; in another, a young woman encounters her estranged brother and secretly follows him through the city “simply for the pleasure of watching him walk.” “The Siege,” set in ancient India, is a mythic story of marriage and motherhood. “The Laughter Artist,” first published in the Kenyon Review, follows a woman who is a student of “the body’s intimate noises.” “Beauty was a mathematical certainty that arose from a precisely correct combination,” observes the narrator of “A Simple Composition.” That combination is luminously achieved in these stories.

Over the summer, I spoke with Swamy on the phone and through email about her approach to short story craft, the relationship between sensory pleasure and art, and what calls her to writing.

—Yasmin Adele Majeed

Yasmin Adele Majeed

When reading A House is a Body, what drew me into the work is that it’s so driven by desire, and so I’m curious about what desires and questions shape your own work.

Shruti Swamy

What calls me to writing is a deep mystery that I can spend my whole life contemplating. I’ve thought many times, where do these stories come from? Why do I feel compelled to write them down? Why do my thoughts take on sentences that have very specific rhythms or words?

It’s such a pleasure and privilege for me to put my work in the world and have a readership of any kind, and to hear that it’s resonant with people. But there’s something sacred about the practice of writing—of sitting in a room and trying to navigate through language, experience, sensation, pleasure, desire. I have a lot of more complicated ideas about why I think writing is important or why I think representation is important—and I believe in them—but at the most basic level I write because it just feels pleasurable to me.

YAM

What you’re talking about in terms of mystery and pleasure resonated with me in the reading experience, and comes through on a craft level in the stories. The way the short story form has been taught to me is often in terms of its strictures, and your stories—which I can tell are so rigorously constructed—also have a looseness and an instinctual, sensual approach to the way they’re crafted. How do you develop the shape of your stories?

SS

Yeah, I think that there’s a real tension. I was watching this YouTube video of Christine and the Queens with my daughter who is two years old, and I was like, this is it: there’s tension and there’s looseness. I think that might be what I love in short stories. I love the tension, and finding looseness in that, and space.

“Blindness” is a really extreme example of a story that I intentionally put a lot of space for people to stand in. I think I start with too much space in my stories and then I’ll have a wonderful reader be like, “I literally have no idea what’s going on, this is all in subtext.” [I’m] often taking stuff that I’ve buried in the text and pulling it out a little bit more directly so that the reader isn’t just like, “Okay, I have a mood but like what else is out here?”

I’ve been thinking a lot about what a short story is and what a short story can do. The stories I’ve loved and learned from were all written by white men basically, and the ones I loved the most were by Andre Dubus, Raymond Carver, and James Salter. I was a very innocent reader for a long time, and being more honest with my own experience as a woman of color and seeing how excluded I was from these writer’s imagination—it was really painful for me. I’ve never been able to go back into those texts without deep pain. And those were the places where I thought I understood what the short story was.

Especially having worked on a novel for a while and coming back to the short form, I’m really trying to understand what makes a successful short story, and I don’t really know anymore because I feel suspicious of the things that I was taught. “Show don’t tell” and all of those maxims—they feel to me like political or moral values that are coded as aesthetic values. They seem like they’re true universal truths. But actually, they do have a bias and a perspective that I feel very suspicious of now.

[The short story has a] feeling of perfection while I think a novel can be very messy because it’s such a capacious forum. Having such a tight frame [in short fiction]—I’m still understanding what that means and how to use it more honestly.

YAM

What do you mean by “more honestly?”

SS

Like “show don’t tell” I think is just, “Be a man. Don’t tell me your ‘women feelings.’ Put that in the subtext.” I think that the short form is asking you to pare down your language, pare down your dialogue, pare it down so that everything that counts. So how do you do that in a way that doesn’t privilege this idea that you can’t say what you mean, you can’t say what you feel, that feelings are “gross”? I mean, I’m obviously going a little bit far in this direction. I don’t think that’s literally what everybody means but I do feel like the way that men are taught to deal with emotions in our culture has something to do with the way we typically look at stories and teach them and assess them.

“Honesty”—maybe it’s not the right word. I think I mean I’m very interested in being a woman of color and being a woman of color short story writer. I want to know what that form offers me as a woman of color that might be different than the ways that it has been used in the past. And I know I’m not the first woman of color short story writer. And I’m definitely not the first to feel kind of suspicious of the form. But I think these are things I need to be exploring even deeper and not just in content, also formally. And I don’t really know what that looks like yet. I’m still reading a lot, almost as research to understand how people have grappled with that.

YAM

Absolutely. Who are some of those writers that you are looking to right now?

SS

Right now I am reading this Indian short story writer, Ambai, her book was published last year by Archipelago Books. She’s in her eighties, I think, and she’s been writing for decades. She’s published many books in Tamil and many of her books are available in English translation. I feel like in her work, I might find the beginnings of an answer. It’s not like she’s doing anything so crazy. In order to create a short story that feels true, I don’t think only the most radically experimental work will fit the bill. I think that there’s a lot of ways within the structures that we’re commonly taught to maneuver, if you’re really careful and intentional about what you’re doing.

YAM

I want to hear more about your journey to kind of collecting these stories together. What were some of the questions and decisions you made in forming the book itself?

SS

I started writing this book over ten years ago so it’s been a really long process of putting these stories together. There have been a lot of different versions of the book over the years.

But the first and the last story have always remained the same in this book. I think it’s a little tricky to draw the lines of what makes it in and what doesn’t, but I was really thinking these are my best stories. I think there was just a point where if I wanted to keep changing out these stories, it would have to just be a completely new book. Because these stories belong together.

YAM

You mentioned that the first and last stories—“Blindness” and “Night Garden”—have remained the same. What about those stories made them feel like the framework for the collection?

SS

“Blindness” in particular felt like the opening to me because it was one of the earliest stories I wrote and it’s one of the strangest, even most difficult stories in the book. I felt like if you entered the collection through that story, you would come in the spirit that I needed you to meet the material. I thought of it as like a door you would walk through that would change your posture as you move through the story, and then that changed posture would help you experience the rest of [the collection].

I’m really interested in the ways we look at things. That story to me about looking at things through not necessarily an Indian perspective—as though there was one—but as a child of Indian immigrants I was raised in a way of seeing things in a double way. The book in some ways is about that framework; the way we can turn things around and look at them from many different angles and perspectives. And that story in particular, I was really interested in looking at mental health, depression, and anxiety through a non-Western, non-medicalized lens, and what that can mean for your soul.

The last story, “Night Garden,” just felt like the end to me. That line “What you have left is what you have,” felt like the end note that I wanted. I remember writing that line, but I feel like I was given that line. Sometimes if I’m very, very open, if I get to a really good state when I’m writing, there are times where I get to listen to the story and the story is given to me. I wrote [“Night Garden”] very quickly, in one sitting, and I didn’t really edit it that much.

Sometimes I write the stories that I need to hear for myself, not in a political way necessarily, just in a small way. I’m often writing about my deepest fears and so I think that the part of me that’s reaching out into those questions is also able to receive some answers about them.

YAM

Hinduism is a large part of the collection, and at times you represent it playfully, as with Krishna in “Earthly Pleasures,” and in “The Siege” it’s much more mythic. Could you talk about the exploration and representation of Hinduism in these stories, and if the current political context of Hinduism— i.e. the rise of Hindu fascism in India—shaped your approach?

SS

I guess I just gave myself the freedom to write what I wanted. I was raised with these stories, but not really with the customs of Hinduism—for a variety of reasons, we stopped celebrating holidays like Diwali around the time I was quite young, and I’ve never felt a comfort or fluency in the Hindu rituals I’ve been a part of. So there’s kind of a double remove for me, growing up in America, and growing up in a family that didn’t do these rituals. It was such a surprise and joy to me seeing how much of Indian culture, and Hindu mythology came very naturally to me when I was writing these stories. It meant to me that there was a link there I didn’t know about, or give importance to before.

But the political context in which these stories might be read in India—that was largely absent in my consciousness when I wrote them. If there was some critical voice that arose from that context, I wrote in defiance against it. These stories, these characters—I feel like they are mine because I’ve loved them. Part of fundamentalism is the flattening of nuance, the flattening of a diversity of narratives into a single story. I wanted to resist this flattening by letting these characters be alive in my mind, on my terms, which actually feels to me like theirs.

YAM

I was just listening to an interview with Garth Greenwell where he says that “sex is one of our most dense and complicated acts of communication and self-making,” and I felt that was true of these stories. I wanted to hear your own thoughts on the relationship to sex and sensuality in your stories.

SS

Absolutely. A lot of [those scenes] are very ugly and knotted with power. The sex scenes in “A Simple Composition” and “Blindness” felt like negotiations of power to me. More broadly speaking, I think that sensual pleasure is at the heart of what I find to be exciting about writing. I mean, even just being alive—I believe in pleasure, and the pleasure of having a body does that pleasure of being alive, of being able to ride your bike as fast as you can, or eat an apricot, or hold somebody’s hand. Those aren’t superficial things. Those are the core of the reason to be alive.

YAM

Some of that sensuality is achieved in these stories through a move into dreamlike mode. There’s these movements through time or into other realities in these stories. The women in these stories are looking for some sort of release.

SS

It’s so funny, my editor when she gave me her first round of edits she was like, “There’s a lot of dreams. I don’t know if you’ve noticed that.” [Laughs] And I actually had not actually not noticed that there are a lot of dreams. There’s also a lot of mirrors and mirroring which I had noticed. There were also a lot of people physically looking in the mirror, I took some of those out.

Why are there so many dreams in my stories? The idea of karma and reincarnation has been so imprinted in me from such a young age. Of living many lives, of not remembering when you’re born into your life but having that psychic weight of the things that have come before you. Even if that is not literally the way you literally look at the world, there’s ways in that that can serve as a very potent metaphor.

I guess I was offering that these boundaries can be more porous than we think they are. And what would that look like, what if these things weren’t so linear? What if things were cyclical? What if dreams do mean something?

I think about that Ursula Le Guin quote where she says that we need artists to imagine what’s possible for the future. That’s a deep function of what art can do. In all these stories I want to open possibilities for people. It could just be ways of seeing their own face in the mirror, or a bowl of oranges on the table—just a way of seeing that makes things feel more beautiful, more interesting, more meaningful.