“As I was writing these poems, I felt that friendship was a constant thing I was returning to.”

June 11, 2020

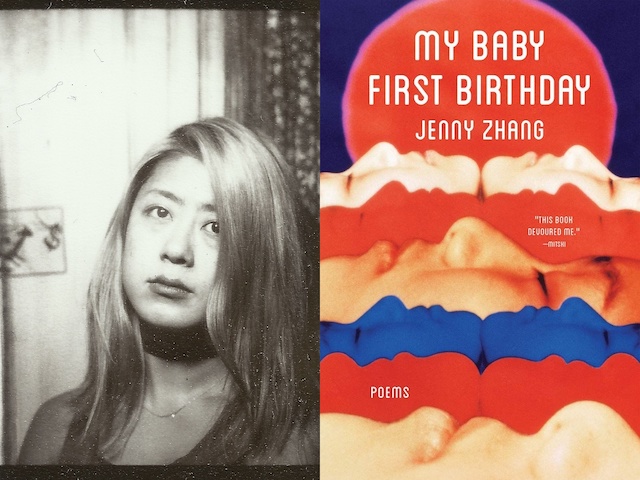

Among the many admirable patterns found in Zhang’s writing, my favorite is her use of malaprops as titles. Her first book, a poetry collection called Dear Jenny, We Are All Find, was published in 2012. Sour Heart, her second book published in 2017, is a short story collection that opens with a story called “We Love You Crispina.” Her latest book of poems is called My Baby First Birthday, which is equally nostalgic, funny and aptly titled.

Zhang’s use of malapropism in her work helped me recognize the struggle, beauty, and humor of language in immigrant communities. It is in these communities where secret languages are created and shared. Years ago, a former writing teacher told my class that we should keep a running list of malaprops we heard, as these were organic ways to play with language. While her work embraces being wasteful with language, Zhang’s word choice feels as purposeful as it is playful in her poetry. She articulates the injustice of racism, misogyny, appropriation, and climate change, while also capturing the dualities of joy and pain, beauty and vulgarity, and tenderness and violence. Reading My Baby First Birthday is reliving the experience of “being baby” through the four season cycle.

During my time as an intern at AAWW a few years ago, I found a copy of Dear Jenny, We Are All Find in the AAWW space library, where I spent countless hours reading Asian-American anthologies, poetry collections, and novels. I read the copy on an NJ Transit train ride from Penn Station to my hometown in New Jersey. Reading Zhang’s work felt like running away to somewhere that was just for me, and such was the case in my experience reading My Baby First Birthday. I could not have predicted that I would be interviewing Jenny over the phone years after reading the copy of Dear Jenny. We talked about the seasons, purity, 90s professional figure skating politics, vulgarity, and friendship: all prevalent themes in My Baby First Birthday, out now from Tin House.

—Ruth Minah Buchwald

Ruth Minah Buchwald: I’ve been reading and enjoying a number of these poems over the years, as they’ve been published in various magazines and websites. Can you speak about organizing them by season?

Jenny Zhang: Time is not real and is real. It is not linear and it is. It’s the most incredible thing that we travel through. This book is called My Baby First Birthday, and I owe my mom credit because she is a poet who may not recognize herself as such.

Years and years ago, there was this Facebook photo of me on my first birthday. I was sandwiched between my uncle and my dad. I looked like this huge bundle because it was winter in Shanghai and there’s no heat. My mom had commented underneath that, “My baby first birthday.” I thought that was so sweet. It split up all the neurons because I was like, “What does that mean? Is it my baby first birthday or is it her baby first birthday? And do we all have baby first birthdays that we remember? Do not any of us get to? Do some of us not get to?” And that became an esoteric phrase that I returned to again and again.

I was thinking about how I’m 36, but in China I’m 38, or maybe even 39. Some people even believe that the nine months in utero also counts, so by some accounts, I’m almost 40, which I always thought was funny because there’s such an obsession with youth. What is the point of these milestones? It’s a slippery, elusive thing.

RMB: This collection has a lot to do with the act of being vulnerable in front of the people you love, whether they be family members or romantic partners or friends, but it also has a lot to do with the feelings of freedom and emergence. What do you make of the cycle between debilitation and revitalization?

JZ: Wanting to be loved and wanting to present yourself as a potential candidate for love are debilitating because they make us cycle through all the times that we weren’t loved and all the times that the people who are supposed to love us aren’t loved.

I was really interested in the concept of baby because a baby’s ego doesn’t intervene to say, “Hey, you’re in danger!” When you’re a baby, you’re a baby. It’s as pure as it can get. Your needs are not driven by whatever psychological defenses and troubles that have built up. It was this yearning to be as pure and authentic as a baby, but with the reality that sometimes, that can make someone so vulnerable to abuse, rejection, and further pain. We select those pains and rejections and abuses. They accumulate and can be debilitating at a certain point.

There can be a point where it is too much to bear: to feel like you’ll never make yourself vulnerable because that is the only guarantee that you’ll ever feel pain, to never again seek love, affection, and care because that’s the only way no one can deny that to you. It’s inhuman. That’s why I was interested in a four season cycle because it takes so much time. We go through all these cycles and at the end, you’re still burned, but you’re a little bit more ready to emerge and try again. And you’ll never try again in the same way, for better or worse.

RMB: The weight of being a daughter, or child, is heavily felt in your work. Your short story collection, Sour Heart, is a lot like My Baby First Birthday, in that your narrators’ innocence is affected by consciousness of their bodies and identities. How was the process of compiling these poems, which feel like a collective ode to the loss of that innocence?

JZ: I took a really long time with these poems. I wanted to keep them lying around and then go back to see if they still meant anything to me. There was this period of time where I had considered not publishing poetry anymore—I think it was right after Sour Heart came out and it’s hard now to disentangle what is a “pure” desire to stop sharing my poetry and what was warped by my brief experience being in the spotlight and in public. There’s something so impure about that, even though it’s necessary to promote so that people can buy the book and I can make a living. I just wanted to hide and write.

I was with these poems for a while, writing and not thinking about them as a book at all. I was writing to write and writing whenever I felt like it. I wasn’t even aware really of any overarching themes until I had gotten to a point when I felt like enough time had passed.

I started looking at and printing out every single poem I had written in the past eight years or something. It was an agonizing process of looking everywhere—there were poems that had notes on top that said, “Not finished!” and “Needs revision!” It was like going through my subconscious of the last eight years. It was like going through a dream journal: this inventory of all the times I needed to escape from the public world into my private world.

RMB: I love your poetry because a specific type of anger you write about is hypocrisy. You’ve said that you wrote the poem “ted talk” when an unnamed publication for people who enjoy luxury products commissioned you to write a poem about global warming, which they then passed on. Are there other poems in this collection that you’re relieved to see in this book and not elsewhere?

JZ: I had been commissioned to write some poems about climate change and global warming. The editor delicately told me that these poems would essentially alienate their readership. I couldn’t see how it was possible for me to write a poem that didn’t address the absolute annihilation that we’re trying to act upon the planet, so I passed. I’m glad that it ended up in this book.

And I don’t mean to call out one publication. It’s all publications and all media. It’s such a trap.

Even with all the stuff I put out there, still there’s shock that I’m received by when I don’t act like a submissive, quiet Asian girl and they’re like, “Whoa, why are you not going along with the exploitation of you?” So, I think that because of all of those experiences that have happened not just to me, but to almost all writers of color, where someone asks, “Why won’t you play along with being a little token and making us look good by inviting you to be a part of our thing?” Because of that, it was really healing to publish a book of poetry.

I specifically wanted to publish with a small press. There’s no way of opting out of capitalism right now, but I want to try as hard as I can to work with people who are not under the spell of capitalism as much as possible, so I wanted to work with a small press. I wanted to publish poems that are too silly or too angry to be published in big publications, but that’s where I needed to be.

RMB: I’ve been interested in your admiration for Philip Roth’s writing, particularly his use of vulgarity, which is also prominent in this collection. Not only does it bring humor to both your and Roth’s work, but I think it also subverts a lot of the expectations of Asian Americans now feel that Jewish Americans felt when Portnoy’s Complaint was released. Can you speak more about the role of vulgarity in your work?

JZ: It’s been a really long time since I read that book. If I read it now, I would feel that he’s actually kind of annoying and super hateful towards women and he’s a bit obsessed with his dick and it’s like, get over it.

I was desperate to read something that wasn’t so contained. There’s nothing dishonorable about writing about the body and writing about the absurdities of the private experiences we have with our bodies. I feel like the people who have suffered the most have the best humor and that’s what people who haven’t suffered that much will never get.

Cultures are closed off about sex and the body and are also the most obsessed about those things—I never want to be part of that. I always want to be part of openness, tenderness, and healing.

With the book, I was so interested in innocence and purity. What does it mean to be innocent? One of my first memories of loss of innocence was when this kid, who was like that one kid in your elementary school who tells you everything you’re not supposed to know, yelled, “Fuck!” one day when she dropped a pencil or something. I didn’t know what that word meant, but I noticed everyone around me had a physical reaction and I was like, “Wow, this is an incredibly powerful word. I’d love to be able to wield that power and play with it.”

When you’re a kid, you “lose your innocence,” and then you’re like, “Oh, can you still love me?” That’s a theme in Sour Heart—that I’m not good anymore. “Will you still love me like I’m a baby?” It’s often that the answer is no, and it’s a devastation to me and maybe to others. These poems are also reenacting that question of “Can you still love me?” Even though I’m using these filthy words, disgusting words, curse words, and words that people don’t like to see. Can you see past that? Underneath that is a baby, like a poem baby.

RMB: That’s definitely what’s drawn me to your work. Every young girl has such a dramatic relationship with innocence and losing it. It’s always like, “This is the marker! The day I change!” Everything’s so heightened then that it just stays with you forever.

On a lighter note, There are a few poems that mention prominent ice figure skaters from the 90s, like Tonya Harding, Nancy Kerrigan, Kristi Yamaguchi, and Michelle Kwan. The passion East Asian women have for figure skating politics has always intrigued me. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the effects Olympic figure skating had on women during this time.

JZ: I think because it is the perfect merger of restraint and power, there are so many dualities. I think that duality is such an important part of East Asian cultures: to have beautiful form, but to have maximum wattage behind it. To be so strong, but also be so delicate. To be bursting with artistic flourish and creation, but to also be so controlled.

Michelle Kwan was an alternate and she was in the Olympic Village, but never competed. Of course she got her chance later, but when she won, there was that racist newspaper article that was like, “China Beats Out US,” and she was on the American team. It was this feeling of why must all of our successes be so marred with indignity, dishonor, and shame? This feeling of why do we have to be lowered always to a level that we never wished to be at? It’s all very stirring to me and I don’t even think I knew that as a child, but I must’ve been drawn to the image of grace and power. I wanted both. I wanted to be beautiful and I wanted to have personal power. One without the other would’ve been imbalanced and I think even then, there was something that drew me to that image.

RMB: This collection is dedicated to your friends. In a recent episode of AAWW Radio from your conversation with other Stanford-alum writers in 2016, you all spoke about how much coalition has been foundational to your writing. I love this collection for being a testament to the people in your life who celebrate loving literature. It reminded me that the act of writing isn’t selfish; it’s actually a very involved process from the beginning. Can you speak more about friendship?

JZ: It’s been really interesting because Sour Heart was so focused on familial bonds and relationships. Friendships are different because true friendship is so freely given, taken and received. True friendship does not involve the idea of duty, which one willingly acts upon.

I love this idea that there can be a relationship that is based on reciprocity, mutual admiration, and mutual care, this idea of a relationship in which you can be cared for, but also be free. As I was writing these poems, I felt that friendship was a constant thing I was returning to.

Some of these poems were pulled from text messages I had with my friends. Texts are poems by nature because they have line breaks and are not linear. They are where you don’t have to serve grammar and syntactic rules. It became this site of generating poems. Texts are the poems that my friends and I will send each other as expressions of care and tenderness that I have felt in my life, so I wanted to honor that and thank my friends for having been there for me in that way. Hopefully, in some ways, I’ve been there for them.