Migrant and Asian sex workers have long advocated for rights, not rescue, creating cross-racial and transnational networks of care along the way.

April 6, 2022

One year ago, in the spring of 2021, people here in the United States and across the world grappled with mass violence committed against Asian women after eight people, including six immigrant Chinese and Korean massage workers, were killed at Asian spas in the Atlanta area. The murderer, a white man, admitted to targeting Asian sex workers because of his own shame and guilt around “sex addiction,” at odds with the anti-sex beliefs of his conservative Christian upbringing. While March 16, 2021 is framed as a horrific one-time tragedy caused by a “lone gunman,” it is difficult to separate these events from the ways Asian spas and massage parlors remain systematic targets of patriarchal violence, whether from anti-prostitution police stings under the guise of white saviorism or anti-trafficking organizations that frame all workers as victims.

The Atlanta shootings shattered the illusion many in this country have about Asian women’s model minority status by prompting a recognition of Asian women who are working-class migrant sex workers, fetishized and victimized by white patriarchy. Personally, Asian femmes like myself have understood that our place in the American imagination, since the foundation of this country, has been informed by the ways American soldiers treat Asian women abroad at military bases and during wartime; how migrant Asian workers are treated here in the United States; how Asian femmes are depicted in U.S. media and movies; and even how we are written into law. To the American imagination, we are the Lotus Blossoms, Dragon Ladies, and Yellow Peril, all in need of saving and extinguishing. Disposable.

Long before the Atlanta tragedies, so-called radical feminists have debated how to situate the experiences of migrant Asian massage workers and sex workers, often claiming they are all victims of human trafficking. Those pushing for the decriminalization of sex work have been called privileged, the “pimp lobby,” and accused of glamorizing prostitution at the expense of women and girls in the Global South.

“We thought Asian massage workers and sex workers would be treated differently after the shooting,” wrote Elene Lam, the Executive Director of Butterfly, a support network for Asian and migrant sex workers, in a statement for the 8Lives Vigil hosted by Red Canary Song one year after the shootings. “However, they continue being targeted by the hate, violence, laws, and law enforcement, particularly the racist and anti-sex work organizations. They are silencing the Asian workers by calling them ignorant trafficked victims.”

To add to the tragedy of losing eight lives to racialized, gendered violence last year in Atlanta, the victims are now unable to speak for themselves. They are unable to define their own relationship to their work and their identities. We must now call them “victims” because they succumbed to their injuries, not because of what their jobs or ethnicities or immigration statuses were.

The ideological arguments that frame all sex workers as trafficked victims strip away agency from migrant sex workers and sex workers in the Global South. “I am not a trafficked victim. I use my hand to support myself and my family,” says massage worker Ching Li, through a message shared by Butterfly. “Please stop imposing your moralistic, colonial, and religious ideas on me.” From my experience listening to migrant sex workers and sex workers in the Global South, they, like their North American counterparts, also want decriminalization, rights (not rescue), and believe sex work is work. Based on current material conditions and needs, these workers do not want to “end prostitution” even if they do want opportunities to exit the trade at their own volition.

Much of the global sex worker movement has been driven by and inspired by workers in the Global South. One prime example is the establishment of International Sex Workers Rights Day, an international holiday that sprung out of a sex worker collective in West Bengal, India, Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (দুর্বার মহিলা সমন্বয় সমিতি), often refered to as Durbar or DMSC. On March 3, 2001, Durbar hosted a festival for 25,000 sex workers in Kolkata. On the same day the next year, Durbar invited sex worker organizations from across the world to commemorate the day together. The holiday is now celebrated annually on March 3.

“We all came under the same umbrella,” Bharati Dey, mentor for Durbar, said during a panel on Sex Work in a Transnational Context in 2021. “We raise our voices on the same day. Sex work is work. We want our rights as sex workers.”

Durbar has been a ground-breaking organization since its formation in 1995. Initially, its founding members came together under the shared goal of HIV/STI prevention, but they soon began organizing on a number of other issues including police harassment, access to financial services, their children’s education, and other sex workers’ rights. By August 1995, the collective formed the largest and first-ever sex worker-owned banking co-op in South Asia, USHA Multipurpose Cooperative Society Ltd, providing members with non-discriminatory banking as well as financial security and mobility. In November 1997, Durbar hosted the first National Conference of Sex Workers in India; its rallying slogan was “sex work is legitimate work, we want workers’ rights.”

“Earlier, when we used to advocate for ourselves, we rebranded ourselves as HIV/AIDS advocates, an intervention program we have,” Dey shared. “When we used to approach people for this intervention work, they wouldn’t believe us. They used to think, ‘This is a sex worker, how can she do health work? She isn’t educated, she’s illiterate, she has no knowledge of this work.’”

Sex workers are continually being underestimated and left out. In 2012, after immigration restrictions prevented sex workers from attending the XIX International AIDS Conference in Washington, D.C., Dey with Durbar organized the Sex Worker Freedom Festival in Kolkata. The five-day festival was held at the same time as the AIDS conference, and more than 667 participants—including sex worker organizers, allies, gay men, and people who use drugs—from over forty countries across the globe attended. Extensive visa regulations for sex workers and people who use drugs prevented those who are most impacted and often on the frontlines of disease prevention and harm reduction from attending the global AIDS conference. But Indian sex workers refused to be left out of the conversation. They created space for themselves and other workers, including sex workers from countries across Africa, who in turn took what they learned from Indian organizers to create their own curriculum.

Sex worker organizing has ripple effects across the Global South—workers universally want to be liberated, safe, and in community.

After the Freedom Festival, sex workers from Botswana, Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe visited two Indian sex worker collectives, VAMP in Sangli and Ashodaya Samithi in Mysore, to collect organizing strategies to implement within their own communities. As Grace Kamau, regional coordinator for African Sex Workers Alliance (ASWA), recalled on the Sex Work in a Transnational Context panel, the sex workers who traveled to India “learned about the model sex workers were using in India and how sex workers are implementing [that model]. Sex workers from Africa, we took the learning. We took it and put in the context as Africans, and from there we get the African Sex Workers Academy. The Academy is a program that brings together sex workers from Africa.”

The Academy launched in 2015 and is held several times a year over the course of one week with different national cohorts from across Africa. It hosts workshops and art advocacy sessions to develop organizing skills, share best practices, strengthen national sex worker movements, and build networks across the continent.

Predating all of these groups is a Thai sex worker organization, EMPOWER (Education Means Protection Of Women Engaged in Recreation), which was founded in 1984. The formation of EMPOWER is especially noteworthy given the particular stereotyping sex workers in Thailand experience due in part to the country’s massive sex tourism industry, which grew rapidly during the American war in Vietnam to meet the demands of U.S. servicemen. As a result, Thai sex workers are portrayed as exploited victims of war in Western media. In 2007, EMPOWER released a print publication to help answer the question, “How can non-sex workers learn from the way we sex workers define our work and our lives?” In the book, titled Bad Girls Dictionary, the term “documentaries” is defined as “sneaky-cam footage of sex workers, bars, brothels and sometimes customers; interview with sex worker filming her in dark or blurred face or just her hands for her sad story; film her poor rural home village and interview with greedy or stupid or tragic family member.”

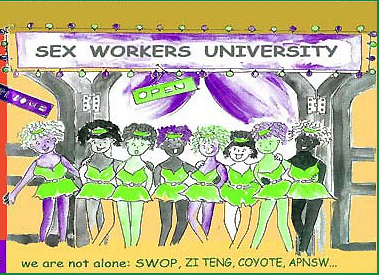

Since 2005, the organization has run Empower University, which has nine centers in four provinces in Thailand and educates sex workers on topics such as political strategy, labor rights, migration, business, and health.

“Sex workers have been organizing against criminalization as EMPOWER for thirty-six years,” Mai Junta, an organizer with EMPOWER, shared during an Asia Pacific Social Forum panel on sex work criminalization in South and Southeast Asia in February. “Criminalization keeps us outside the labor law. It means we cannot access financial services for credit cards or loans. A criminal history means we cannot get visas to travel to some countries. We cannot access other rights, for example social security, labor rights protection, and justice before the law.”

EMPOWER also made history by opening up the first and possibly only sex worker collective-owned and run bar, Can Do in Chiang Mai, northern Thailand. Established in 2006, Can Do provided a way for sex workers to respond to exploitative working conditions in bars. In a bar owned by sex workers for sex workers, they are able to build a space with fair pay and labor expectations, rights and protections, and safe practices and facilities.

“Most sex workers are women and mothers, all are family providers who work to raise the quality of life for the family,” Junta said of her peers. “We have done many jobs before sex work and are not doing sex work for survival alone.”

These initiatives rising out of sex worker organizing from across the globe demonstrate how the people we were meant to view as trafficked, victims of pimps and imperialism, and lacking any agency are in fact the ones speaking up the loudest and advocating for themselves. They are also the ones working hardest to ensure workers aren’t being exploited or trafficked.

As those of us who are grieving continue to remember the Atlanta victims and the two Asian massage workers killed in Albuquerque, New Mexico earlier this year, we must be mindful and intentional of the ways we discuss the lives of those labeled as victims, even after they have departed this world. We must also extend our solidarity to those currently advocating for safer work environments and destigmatization, so that we may prevent future tragedies.

At the 8Lives Vigil in March, Red Canary Song organizer Yves Tong Nguyen took to the mic to remember those who had been killed last year in Atlanta: “They have already inspired so many people since their deaths, but I want to remind us all that the six Asian massage workers who were murdered that day are not martyrs for our movements. We hope to honor the complexity of their lives and the complexity of their deaths as we continue to try and fight for women just like them.”

With thanks to Sanchari Sur for translation of audio from “Sex Worker in a Transnational Context.“