The majority of Palestinians live outside of the occupied territories, awake within a paradox: If it is a demand of land that tethers us, what do we make of those millions of us without a memory of the land to cling to?

November 12, 2018

“[I]s it possible for nationalism to give up its desire for a name that is complete, singular, and coherent; is it possible for nationalism to endure a name that is more reflective of the inner life, one that disarrays more than coalesces?”

–Kevin Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet

Outside of the spectacle of history, exile feels mostly shapeless, mundane, though it hangs like drapes over the windows, clouding the entrance of sunlight, mediating all encounters. This year marks seventy years since the Nakba, “The Catastrophe,” the assigned historic beginning of mass Palestinian dispossession from our ancestral land, though it began much earlier, in the economic calculations of British imperialists. Today, the majority of Palestinians, nearly eight million of us, live outside of the occupied territories, awake within a paradox: If it is a demand of land that tethers us, what do we make of those millions of us without a memory of the land to cling to?

*

Beginning in late March of this year, in commemoration of Land Day, tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza launched the Great March of Return. Continuing for the past several months, the march is a historic act of visible resistance demanding the right to return to homes and land the state of Israel has seized, has been seizing, over the last seven decades. In the context of the open-air prison of Gaza, in the face of some of the most violently imposed conditions of occupation in the world, where two-thirds of the population are registered as “refugees” a few miles from their land of origin and nearly 80 percent of the population is forced to be dependent on outside aid to survive, this march is more than a contained moment of protest: it is a public refusal to die slowly in secret, it is a rebellion announcing the dignity of life in the uninhabitable cage, it is science fiction. Over 175 Palestinians have been killed participating in The Great Return March, over 15,000 have been injured, facing live ammunition from Israeli soldiers. Yet the people keep returning to protest, week after week.

A photojournalist who grew up in Gaza, Mohammed Zaanoun has attended and photographed the protests since they begun: “There is always a danger, so every Friday I feel that I will not return home.”

In a 2017 interview with Anera, a year before the Great Return March begins, he is asked if he has a favorite photograph: “My favorite photo is one I took of a girl jumping rope, and behind her is a building destroyed by war. It expresses strength and power. After death, there is life. It shows the real Gaza—where people find life amid destruction. I love to show different sides of Gaza, both its beauty and its sadness. I love to show all the details, streets, children and homes.”

*

A shared lexicon of resistance, a public demand asserting a right to return, becomes necessary as a means of stymieing the inflicted wound. The material condition of genocide, an unrelenting project of Palestinian depopulation, cannot be disentangled from the urgency of the nationalist narrative—a refusal to forget, a refusal to be eradicated or to be erased from the archive.

Even with decades of records documenting this language of resistance, it remains difficult to articulate my personal relationship to Palestine—a place my parents and I have never seen, yet still feel wholly accountable to. Most of what I know of Palestine remains this exterior responsibility. But what of the Palestine murmuring in the wells of my body? A collage of tones, an incantation: the sound of my mother’s voice, the Darwish poem my father recites in the kitchen, the memory of my cousins looking out a window in Lebanon, toward the border’s horizon.

In his book The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, Kevin Quashie explores representations of “quiet” in black culture to push back against the notion that black representation is only useful insofar as it articulates a kind of recognizable resistance, which, as he points out, inevitably limits the possibilities of full expression. “Such blackness is dramatic, symbolic, never for its own vagary, always representative and engaged with how it is imagined publicly,” writes Quashie. “[B]ut all living is not in protest; to assume such is to disregard the richness of life.”

The Palestinian flag and keffiyeh remain ubiquitous public symbols of anti-colonial protest around the world. But I wonder: What kinds of nationalism are possible for Palestinians in diaspora if our attachments to nationhood remain imagined? If many of us never physically return to our historic indigenous lands in Palestine, what other forms of less recognizable resistance become enabled in our dispersed yet tethered refusals to forget or to die? What forms of quiet resilience and interior counter-mapping must also coexist alongside a public life of demanding recognition?

To meditate on an interior Palestinian identity within exile, to define who we are to ourselves for ourselves, outside of the violent logics of colonial interlocutors, is an urgent necessity. It is the precursor to languaging a future in which we can exist not only as symbols of public resistance but as unlimited, borderless possibilities. Art rooted in the interior spaces of our identities provides crucial lent space for imagining this yet-to-be articulation.

*

“…Perhaps / history wasn’t born as we desired, because / the Human Being never existed?”

—Mahmoud Darwish, “Don’t Write History as Poetry”

While acting as a consultant to the United Nations in 1983 for its International Conference on the Question of Palestine, Edward Said suggested a photo essay featuring Palestinians be hung in the Geneva assembly hall. Several participating nations, including neighboring Arab nations, objected to the photo essay, but settled on a compromise that allowed the photos of Palestinians to be hung without their captions. In response, Said wrote After the Last Sky to fill in these silenced spaces with a meditation on interior Palestinian subjectivity. On the concept of looking for “quiet” within representation, Quashie writes, “Quiet, instead is a metaphor for the full range of one’s inner life—one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears. The inner life is not apolitical or without social value, but neither is it determined entirely by publicness.”

In After the Last Sky, Said makes a distinction between the interior (al-dakhil) and the exterior (fil-kharij) within Palestinian identity. The exterior is a space of public denial, state dispossession, and exile since 1970, but one reading of the interior, writes Said, is “that region on the inside that is protected by both the wall of solidarity formed by members of the group, and the hostile enclosure created around us by the more powerful.” This dialectic tension between external tragedy and internal solidarity is a site of inherited trauma but also a site of creative resistance: “To be on the inside, in this sense, is to speak from, be in, a situation which, paradoxically, you do not control and cannot really be sure of even when you have evolved special languages… that only you and others like you can understand.”

This work of “endlessly attempting to define what is yours on the inside,” is also dream work: a chance to imagine Palestinian identity as a collaborative one, rooted in constant attempt. What if “return” is not a fixed point, but a relation we invent and reinvent within a persistent choice to share, to struggle, to live in co-dignity with the land, wherever we walk it. If we can never return in the embodied sense, maybe the “right to return” also insinuates an abolitionist demand: to abolish the very concept of settler border space and all state technologies that demarcate, that enforce a violence of distance. Maybe being Palestinian can mean being alive to the revolutionary capacities of language to create who we are in the absence of permission.

*

The archive is a battleground, settler colonialism cannot win through weaponry alone. Settler technology must also seize memory, erase all forms of indigenous legitimacy, destroy the evidence that a people existed prior to development—full of breath, grief, laughter. According to the Arab League, 80,000 Palestinian books and manuscripts have been stolen by Israel since 1948. In August of this year Israeli forces bombed Said al-Mishal Cultural Center in Gaza City, where young Palestinians had gathered to play music, dance, act in plays, and produce other forms of collective art and performance.

The battle of the archive is also a battle to retain claims to humanity. In this way, Palestinians living in exile also feel the weight of responsibility to iterate we and exist over and over again, to appeal with facts, equations, and anecdotes to merit sympathies of state actors and allies. In other words, to demonstrate our innocence to the armed guards. But this forced logistics of proof replicates another violence. We are trapped in a cycle of explaining our right to live to institutional arbiters within a structure that normalizes humanity as merit based. The history of settler colonialism from Turtle Island to Palestine is also a history of rationalizing myths that legitimate domination, extraction, and bondage.

We must invent another kind of mapping, another kind of archive. “A colonized people is not alone,” wrote Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth. “In spite of all that colonialism can do, its frontiers remain open to new ideas and echoes from the world outside.” If the colonial project of Zionism relies on rewriting history in the service of a heavily guarded ethnostate, we resist across the Palestinian diaspora by crafting forms of representation that invite an echo of universality—an echo of closeness.

*

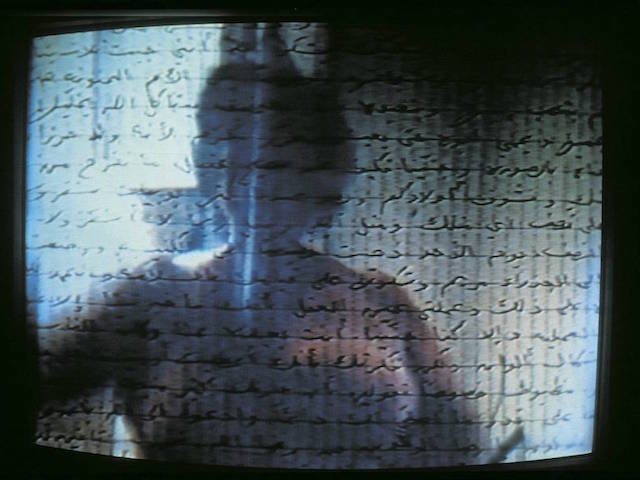

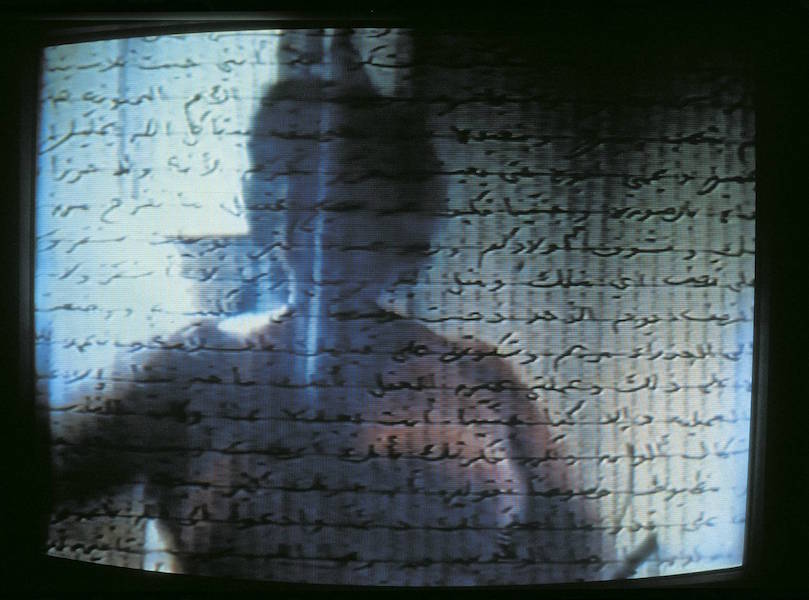

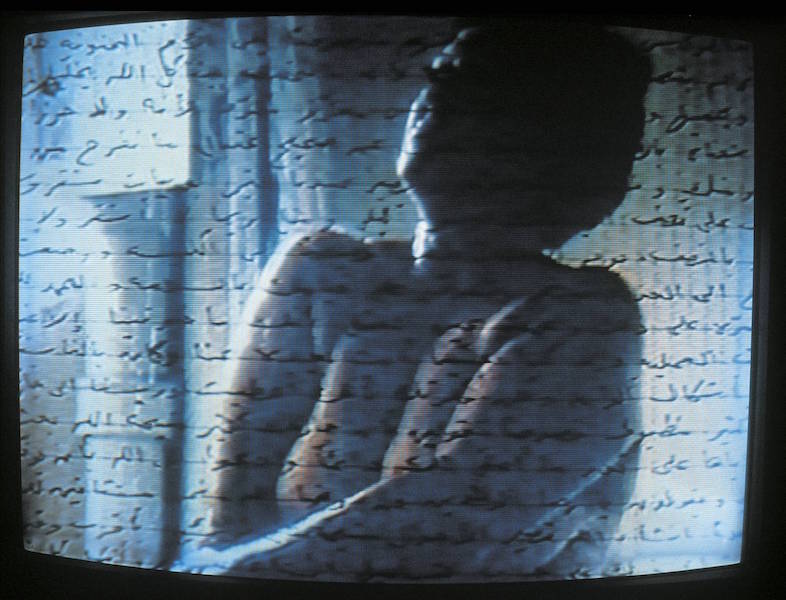

In Mona Hatoum’s video piece “Measures of Distance” (1988) the complex intimacies that bloom within exile animate the screen. Hatoum, a Palestinian artist born in Beirut, who remained in exile in London when war broke out in Lebanon in 1975, records a conversation with her mother in the shower, while projecting text from her mother’s letters, then reading aloud their English translations. The sound space of the video holds their conversation in Arabic, the rush of the water in the shower, the street noises spilling in from the outside, and Mona’s translation of her mother’s words—all overlapping, intermingling.

The visual space inscribes Arabic text onto her mother’s bare body, the tenderness of the familial intimate encounter always carrying the weight of explanation. “I personally felt as though I had been stripped naked of my very soul. I’m not just talking about the land and property we left behind… but our identity and our sense of pride went out of the window,” writes Mona’s mother about being displaced from Palestine.

I send the video to my mother, another Palestinian daughter born a refugee in Beirut, who has lived in the United States away from the majority of her family since 1986. She lives a few states away from me now, and after she watched the video, she left me recorded voice messages over WhatsApp. These are some excerpts:

Message 1 (7:42pm): Hi habibti Zaina, I’m so sorry it took me forever to get back to you about the video, I’ve been really busy this past week… so I sketched some points, I’m going to go over them because my fingers really hurt from cooking and stuff like that. I’m gonna just go over them hayk sporadically… you can delete what is nonsense to you… these are things I felt like sharing… when she first started talking it was such an emotional mix… feelings towards my daughter, missing you now that you are far away, and remembering what my mom was saying to me when I was far away from her.

Message 3 (7:46pm): Mentioning the war it just gave me a million different feelings and thoughts and emotions, of course… the anger and the sadness I used to feel, unable to visit my parents, talk to them over the phone, even write letters to them… and just I remember feeling grateful at moments that I am so far away from the war but it was a lot of sadness and a little bit of gratitude… sometimes we were able to arrange days ahead of time and the phone call would be so costly… but I didn’t care, I wish I could have sold my blood to pay for it…. I needed it more than food and air, to talk to my mom.

Message 5 (7:52pm): …I noticed the mom describing how intimate they got talking to Mona, and I recognized that I never had a talk about intimacy with you, you know, I don’t know… I never had a talk about intimacy with my daughter, so… I don’t know, it was just such a throwback with memories…

I wonder if intimacy is the first room for all formulations of resistance. Quoting Natalie Goldberg’s Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life, which connects the act of writing to the act of living, Quashie writes, “This quiet is represented by our interior, that ‘place in us below our hip personality that is connected to our breath, our words, and our death.’”

I wonder if the way I sometimes feel closer to my mother when we are not in the same place can serve as a metaphor for being Palestinian.

*

While looking for photos of Gaza that don’t include maimed limbs or strewn corpses I find a young girl in a field of mustard flowers, petals pressed against her eyelids. I know her, I think inside of myself, or maybe she is the portrait of a precedent alternative for a future tense: a girlhood of land. Is it the settler or the exile in me that tries to find myself everywhere? Yellow is the only thing that makes sense. Yellow yellow yellow yellow yellow.

*

“a scatter vapor of earth / a trance of metal / where from here / i am all tunnel”

—Suheir Hammad in “The Gaza Suite: Zeitoun”

Much has been written in recent years of the connective threads of solidarity between some anti-imperialist black organizers in the United States and Palestinians, with many pointing to the moment when members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) identified Zionism as a form of settler colonialism in a pamphlet they published in the late 1960s titled “Third World Round-up: The Palestine Problem.” The contemporary iteration of this solidarity has been led primarily by black scholars, poets, and activists including Angela Davis, June Jordan, Alice Walker, Robin Kelley, Aja Monet and members of the Florida based liberation organization The Dream Defenders, to name a few.

One story of entangled solidarities comes from the prison cell of revolutionary George Jackson, former Field Marshal of the Black Panther Party. While held captive in San Quentin, Jackson kept copies of translated poetry from the Palestinian poet Samih al-Qasim, including his poem “Enemy of the Sun.”

O enemy of the sun

But

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist.

This year during the National Prison Strike, a historic coordinated strike action called by imprisoned workers organizing across the United States, a group of Palestinian prisoners released a solidarity statement that began by mourning George Jackson, highlighting his internationalism: “Today, we write to you to once again forge that connection of struggle, despite our different circumstances.” Alongside an explicit language of resistance there is also the quiet act of a prisoner imagining themselves surviving within another’s poem. Though solidarity is most often understood as an external action, what unsettles within the interior of a cell—without an audience, without any promise of return—that enables one to imagine the freedom of another prisoner as inextricable from their own? What moves us towards a recognition of a shared sun the state cannot see?

Shortly after the rebellions in Ferguson in 2014 began, in defiance of the murder of eighteen-year-old Mike Brown, tweets from Palestinians instructed black protestors on how to cope with tear gas. To this day the Aida refugee camp in the occupied West Bank remains the community most exposed to tear gas in the world. Palestinians pointed out that the same US-made tear gas canisters used on Palestinians were also used on mostly black protestors in Ferguson.

The gesture of those tweets is portrayed within a print by Chicago-based Palestinian artist Leila Abdul Razzaq as part of her series #Arabs4BlackPower. Rather than an image of a clenched fist, a tear gas canister, or startling images of violence, the print highlights an ordinary domestic object, a carton of milk, used by protestors in Palestine and Ferguson to soothe their eyes. Instead of focusing on loud images of explicit protest, Leila’s print focuses on the relationshared between two groups of people resisting state violence. Even in the midst of militant rebellion, documented through the hyper-visible medium of social media, there is a quiet at work—an intimacy of care, tools for healing the harmed body, extended by strangers beyond demarcated borders. The story is succinctly summarized in Arabic and also in English.

In an interview about her work with Hyperallergic, Leila explains the stories of life in Palestinian diaspora she depicts include “ones that some don’t deem important enough to write down, or maybe too despicable, or not ‘reliable’ or ‘balanced’ enough to be valid.” In this way she refuses to adapt to binaries of innocence or heroism—Palestinians, like all other workers, are infinitely complex and accountable to the entangled and violent worlds we inhabit. Later in the interview, Leila explains, “[T]here are as many experiences of being Palestinian as there are Palestinians in the world, and none are more ‘real’ or ‘legitimate’ than others.” In another interview with Judy Suh about her graphic novel Badawi, based on her father’s experience as a Palestinian refugee, she explains, “These people aren’t objects of pity, they are subjects of their own narratives.”

*

Could we mold ourselves into a map of shared debt? Is solidarity a national identity? Could return be wherever we are attempting to tell the origin stories of the land we inhabit? To begin again, again in right relation with history and the people who were here beforebeforebefore, are here now, are on their way. To articulate our bonded familiarity in spite of the boundaries imposed by state and capital.

“The fundamental contradiction of the nation-state,” writes Asad Haider in his book Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump:

[A]s Etienne Balibar has pointed out, is the confrontation and reciprocal interaction between two ways of defining the “people.” First, ethnos: ‘an imagined community of membership and affiliation.’ Second, demos: ‘the collective subject of representation, decision making, and rights… the second sense of the “people” is the political one… It is meant to apply regardless of identity.

Speaking, writing, and creating from the Palestinian diaspora is not only a means to count the dead from afar, or to name what has been stolen. How we manage to represent ourselves in the wake of ongoing occupation invites a political national identity that has the power to eclipse norms of categorization that rely solely on physical proximity.

In his ethnography of Palestinian music, musicians, and protest songs, My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance, David McDonald shares the following anecdote from Palestinian rapper Tamer Nafar:

“You see… people don’t understand that Tupac should be considered [a] shahīd [a martyr for Palestinian liberation],” Tamer Nafar explains to me backstage before a rap concert in Ramallah in the summer of 2005. “His experiences are our experiences. His struggles with the police are our struggles with the police. His ghetto is my ghetto. If you listen all he talks about is the ghetto, revolution, politics. And he died because he was willing to speak out for his beliefs… That makes him [a] shahīd, and that makes him Palestinian.”

This should not be confused with conflating or collapsing the experiences of Black people in America with Palestinians, rather it is an expression that the effects of colonization experienced by Palestinians at the hands of Israel—hyper-policing, land theft, mass unemployment, ecological devastation, and the waging of militant resistance in opposition to these violences—are not unique to Palestinians, nor can colonial violence ever be contained to the settlers’ imaginary borders. Instead of emphasizing a detached advancement, we confront the settler project first by confronting the empire within, then by looking outward for all the bodies in the water, reaching out to every hand we can grasp.

In Ghassan Kanafani’s “Letter from Gaza,” written in 1956, the novelist and founding member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine responds to his longtime friend who was urging him to take a teaching position in the U.S., to leave Palestine in order to survive:

No, my friend, I won’t come to Sacramento, and I’ve no regrets. No, and nor will I finish what we began together in childhood. This obscure feeling that you had as you left Gaza, this small feeling must grow into a giant deep within you. It must expand, you must seek it in order to find yourself, here among the ugly debris of defeat.

This “obscure feeling” Kanafani names emanates beyond a sense of national pride, or even a claim to place. What he describes is to define a life not just by who we are, the streets we come from, but by who we owe ourselves to. This is the core subjectivity of Palestinians that proves itself most dangerous to the colonial logic:

I exist only because I exist alongside of you, resisting.

Written nearly 30 years later, “Moving Towards Home,” a poem by June Jordan—the black feminist poet of prolific capacity to build solidarity into language—echos Kanafani’s sentiments by imagining “home” as a shared objective, rather than a stationary location. Jordan layers testimony of state-inflicted and cultural violences experienced by Black people in the United States and globally, with shared examples of violence and ethnic cleansing experienced by Palestinians and others abroad. She ends the poem with an announcement:

I was born a Black woman

and now

I am become a Palestinian

against the relentless laughter of evil

there is less and less living room

and where are my loved ones?It is time to make our way home.

Jordan’s use of “I am become” implies a subjectivity of solidarity that is active, interiorized (“I”), but also constantly unfinished, to become. Borrowing from Kanafani and Jordan’s examples, for Palestinians in diaspora to exist in a constant state of return is an invitation towards a windowed reckoning: the project of Palestinian freedom remains unfinished until all of us severed from history can “make our way home.”

In the preface to her 1996 book of poetry Born Palestinian, Born Black, a text inspired by and in response to June Jordan, Palestinian American poet Suheir Hammad writes, “Home is within me. I carry everyone and everything I am with me wherever I go.”

The literacy of Palestine I seek is in the seeking—a radiating tangent, indebted to sharing; what fills us homeward without explanation.