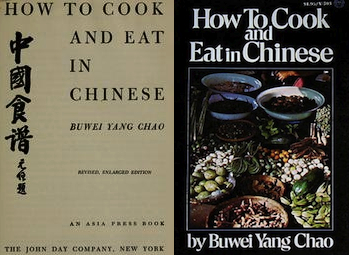

Buwei Yang Chao’s famed 1945 cookbook helped coined the phrase “stir-fry.” “Wrapling” and “rambling,” her words for the simple and ruffle-edged dumplings, were less successful.

November 7, 2012

Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (1945), an odd, earnest, and at times inelegant treatise on Chinese cooking for Americans, opens on a rather inauspicious note. “I am ashamed to have written this book,” says Chao in her author’s note—although, in the most literal sense, she actually did not write it. Concocted “family style,” the recipes were conceived by the Chinese-speaking Chao, translated into English by her daughter Rulan, and, in parts, reconstituted into Chinese-inflected English by Chao’s husband, Yuen Ren Chao, who found Rulan’s version dull. Buwei Yang Chao reports, “It is safe for me to claim that all the credit for the good points of the book is mine and all the blame for the bad points is Rulan’s.” She continues, “Next, I must blame my husband for all the negative contributions he has made toward the making of the book.”

The Chinese propensity for belittling one’s kin notwithstanding, the Chaos were a family of exceptionalists: an Eastern set of Tenenbaums. Buwei Yang Chao was a Japanese-educated physician and self-taught cook, who, among her accomplishments, pioneered the use of birth control in China. Yuen Ren Chao was a polymath professor and scholar of linguistics, child-language studies, philosophy, mathematics, physics, and music at Harvard and Berkeley. His credits include a 1922 wordplay-preserving translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that set off an “Alissu” naming craze in China, the thirties pop hit “How Could I Help Thinking of Her,” and the Gwoyeu Romatzh system of Chinese language Romanization—not to mention lecturing alongside Sartre.

Together, the Chaos wrote a landmark work, perhaps the first American Chinese cookbook to go beyond the chop suey collections of the pre-World War II era. How to Cook is a true and steadfast document of Chinese habits and foodways in a period of rapid change. Andrew Coe’s Chop Suey, his 2009 book documenting the cultural history of Chinese food in the US, recounts the early landscape: In post-Gold Rush San Francisco in the 1860s, $1 all-you-can-eat houses with mixed Western/Chinese fare existed alongside elaborate banquets for businessmen, while in New York, Chinatown’s first outpost arrived on Mott Street in 1873. Within a few years, two Chinese farmers were growing Chinese vegetables on three acres of land in the Tremont section of the Bronx, and by the 1880s, there were a half dozen or so Chinese restaurants in New York. One meal in a Chinatown restaurant was described by diners as both a “rare-done nightmare” and “a rainbow soaked in brine.” Following Chinese statesman Li Hongzhang’s much publicized 1896 visit to the city, the first recipes catering to Westerners began to appear in print. (Interestingly enough, according to Coe, the idea of “chop suey” as an Americanized invention is one of our biggest Chinese food myths—it’s actually Pearl River Delta peasant food.) By 1943, when the Magnuson Act repealed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that had suspended immigration, the classic Chinese-American restaurant formula, and by extension Americans’ palate for Chinese food, was due for an update.

The ambitious Chaos complied, with Buwei Yang picking up dishes from China’s varied regions and social classes while accompanying her husband on his dialect surveying trips. Arriving before the multitude of Chinese cookbooks published in the US throughout the fifties, sixties, and seventies, How to Cook was in a prime position to influence how a generation of Americans would think about Chinese food. It was a timely guide to Chinese-American food that could be appreciated by those on both sides of the hyphen—a cuisine that was coming of age and would gain esteem with Craig Claiborne’s ascension at The New York Times in the fifties. He name-checked Harlem’s Tien Tsin in his historic first “Directory to Dining” capsule reviews column in 1962, and in 1969 awarded four stars to Manhattan’s Shun Lee. By the time Nixon picked up chopsticks in 1972, we were goners.

—

Before you even get to the recipes, the book’s title provides a grammatical hint to the Chaos’ approach: You do not cook “Chinese,” the cuisine, but “in Chinese,” from the obtaining and readying of ingredients all the way to the serving and sharing of food. The analytical duo thought about food, and the preparing and consuming of it, as a language. Dishes are presented in their basic form, with variations, so that in chapter one, “Red-Cooked Meat,” which Chao defines as “stewing with soy sauce,” there are also dishes like “Red-Cooked Whole Pork Shoulder: Plain”; “Red-Cooked Meat Proper: Plain”; and “Red-Cooked Meat with Yellow Turnips.” And Chao’s diagram of “Rolling-Knife Pieces,” for instance, demonstrates how to cut cylindrical objects such as cucumbers and string beans to yield “beautiful combinations of parts of curved cylindrical and plane elliptical surfaces”—a technique I recognized as my own self-developed method for chopping carrots for, say, the decidedly non-Chinese boeuf bourguignon.

Chao also reveals an anthropologist’s devotion to decoding the particularities of Chinese behavior in and out of the kitchen. “Table manners begin with a fight over yielding precedence in entering the dining room. Among familiar friends, it may come to actual pushing, though never to blows,” she writes, although she assures us that in this “wrangling atmosphere everybody feels happy and at ease, because things are going as they should.” Also described is the “dinner-table convention… that everybody is supposed to be reluctant to drink,” giving the impression of a nation of polite yet forceful abstainers.

But when all parties involved reach agreement? The Chinese way of eating, in which one dips in and out of many bowls shared at the table, becomes, in Chao’s rendering, a lovely back-and-forth dance, a way of conversing without talking. Chao writes: “Each person just eats a chopsticksful of this, then a morsel of rice (the rice bowls are always individual), a chopsticksful of that, then a morsel of rice from his own particular bowl, a spoonful of the common soup, and so on, quite casual-like. The result is that you feel you are all the time carrying on a friendly conversation with each other, even though nobody says anything. I wonder if it is because the American way of each eating his own meal is so unsociable that you have to keep on talking to make it more like good manners?”

Extending Chao’s interest in sociability, the book closes with typical menus for banquets as well as ideas for Chinese-style “special eating parties.” Among them is the Crab Party, a gathering to dismantle steamed crabs that are eaten with bowls of Chinkiang vinegar and minced ginger—after which, in deference to the theory that “the more crabs you eat the hungrier you get,” “it is therefore customary to serve some light lunch or refreshments or even a full meal immediately after.” Another favorite is the self-explanatory Watermelon Party. Writes Chao, “When we eat watermelon, we just eat watermelon.”

—

Today, the book’s most famous legacy is the coining of the term “stir-fry” for the Chinese ch’ao, which the author says “cannot be accurately translated into English,” though “roughly speaking,” it may be defined as a “big-fire-shallow-fat-continual-stirring-quick-frying of cut-up material with wet seasoning,” most similar to the Western “sauté.” In the “Meat Slices” chapter, Chao relays a litany of dishes that can be prepared in this way, from “Bamboo Shoots Stir Meat Slices” and “Squash Stirs Meat Slices” to “Cauliflower Stirs Meat Slices.” “Pot sticker” is another success story. On the other hand, “wrapling” and “rambling,” Chao’s words for the simple dumpling and the ruffly-edged dumpling, its folds “like the tails of a goldfish,” did not take. How to Cook also offers a chance for today’s reader to see what life was like on the American frontiers of Chinese cooking, when fresh ginger could not be had for the money, MSG was branded “taste-powder” or “essence of taste” (Chao is not a fan), and the thin wheat discs served with Peking Duck, now commonly called pancakes, went by the sweetly old-fashioned “doilies.” (Beijing/Peking itself went by the Wade-Giles romanization, Peiping.)

Chao’s husband, the playful and groundbreaking linguist Yuen Ren, shows his hand in the book’s use of the gender-neutral hse to stand in for English’s lack of a common third-person singular pronoun. In his sole recipe credit, an overwrought rendition of “Stirred Eggs,” he writes, “Either shell or unshell the eggs by knocking one against another in any order,” in reference to English’s puzzles of opposite words with the same meaning. We cannot be sure which Chao was responsible for the book’s low point, “Egg Stirs Rice,” which uses leftover rice, eggs, and fat to make a quick complete meal: “On Chinese trains ‘Flied Lice with Eggs’ sells almost as fast as sandwiches on American trains,” the Chaos write.

Bad jokes and unpromising beginnings aside, How to Cook—comprehensive, workable, and as serious-minded as it is lighthearted—treated its readership fairly and sensibly, without folding to American tastes and, perhaps more impressively, without making a spectacle of authenticity. If cooking is about homecoming, it is also about setting forth, hungry and ingenious. (Chao writes of buying and cooking a dollar’s worth of sweet peas from a flower shop during her first trip to the US, homesick for the tender pea shoots eaten in China.)

The Chaos’ classic would see updated American and British editions in the following decades. And for those who had mastered its language, there would be a new dialect to learn, with the 1974 publication of Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Order and Eat in Chinese (To Get the Best Meal in a Chinese Restaurant).