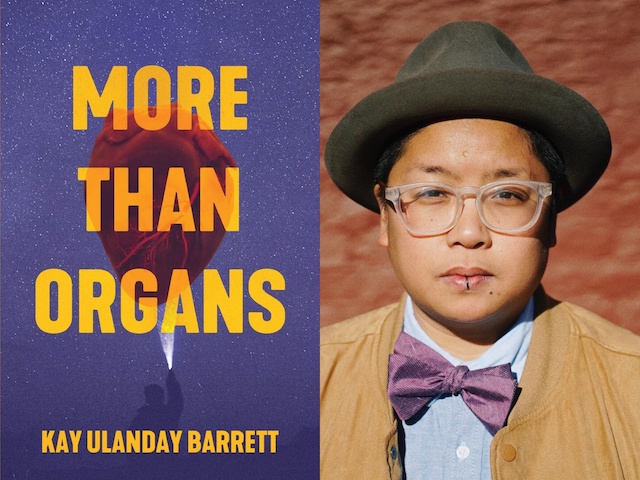

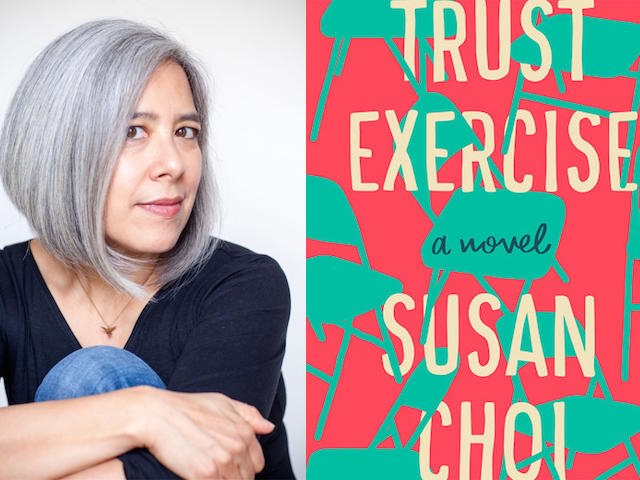

The author talks her long career as a novelist, her obsession with adolescence, and the disruptive process of writing her latest novel, Trust Exercise.

April 10, 2019

Susan Choi’s new novel Trust Exercise begins with the titular act: teenage students at a performing arts school in an unnamed Southern town in the 1980s are told to close their eyes and crawl around in the dark. They bump, grope, and clumsily shuffle past each other in the darkened classroom. It’s an acting exercise, one meant to teach them how to get to their most base selves, and is conducted by their charismatic drama teacher, Mr. Kingsley. It’s also erotically charged. When Sarah brushes past her crush, David, their encounter in the dark begins a sexual relationship whose consequences ricochet through the rest of the novel.

The scene is striking, and sets the groundwork for the misunderstanding, abuse, and coercion that take place as the book moves from the characters’ teenage years into their adulthood. It’s also a repeat.

American Woman, Choi’s Pulitzer-prize shortlisted novel based on the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst, follows Jenny, a Japanese American woman tasked with keeping watch on fugitive militant radicals and the old money heiress they’ve kidnapped. Jenny is on the run too—from the law, for her involvement in the militant left, and from Frazer, an old comrade obsessed with her after an unexpected contact during a party game that is the same acting exercise from Trust Exercise. With the lights off and their blindfolds on, Frazer finds Jenny in the dark and grabs her by the knee. He knows it’s her because of the ridged denim designs on her jeans. The jeans are a detail that Choi also takes to Trust Exercise. As soon as the lights are off in Mr. Kingsley’s classroom, Sarah realizes “her jeans marked her, like a message in Braille.” David, like Frazer, grabs Sarah first at the knee.

It’s fitting, though, that Choi repeats herself in a book about repetition. In each of Trust Exercise’s three parts, she refracts the narrative, looking at the ways in which an experience can be newly understood depending on who’s telling the story. “Repetition is about context,” says one character of the acting exercise where two students exchange the same sentence back and forth, chewing on the words, emphasizing differently, whispering, shouting. The exercise is a staple of the Meisner Technique, and is meant to stress the communication of emotional truth over strict adherence to a script. The book, like the Technique, reconsiders the truth of the previous parts, and in doing so, unravels the very form of the novel. Like Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry and Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, Trust Exercise plays with the reader’s trust. What you think the truth of the story is shifts repeatedly.

Trust Exercise, too, plays with the same obsessions evident throughout Choi’s more than twenty-year-long career: women in the fight against authority and abuse in American Woman, the naïveté and stubbornness of youth in contrast to the perspective of the old in My Education, and the ways those who are different are made violently invisible in The Foreign Student and Person of Interest. Apart from American Woman, her novels are set in and around the campus. Whether high school or university, from the vantage point of students and teachers—for Choi it is a site where sex, gender, and desire butt up against the restrictive, coercive bounds of the institution.

But in Trust Exercises‘s play with narrative, truth, and craft, Choi upends the traditional novel form that she had committed to in her previous books, starting off on a new path of a long and storied career.

—Yasmin Adele Majeed

Yasmin Adele Majeed: I wanted to start out by asking you about the movement from one project to another. After completing My Education, how did Trust Exercise first come to you? Was it was through a particular character, or the narrative form of the novel?

Susan Choi: It definitely didn’t come in terms of the structure. That came much later, really deep into the writing, when the writing reached a point where it seemed to demand some kind of major disruption. But that wasn’t what I had planned.

After My Education, I actually started a totally different project. I don’t know if I’ll ever publish it at this point because I haven’t been able to bring that project to completion. I’ve completed a full draft of it and researched it for years. It was so all-consuming and going so poorly that I started ducking out a side door to do other things, and one of those things was Trust Exercise, which really started as something that I hoped would be a short story. But I’ve never succeeded in writing a short story. Every short story I’ve ever started has unraveled into something a lot longer that either ultimately became a book or that I was never able to finish at all.

At what point in the writing process did that period of “major disruption” appear?

I started Trust Exercise in the same place that it starts now, in that scene in the school with the young theater students who are crawling around on the floor in the dark. I envisioned it as a story that unfolded out of that scene and ended somewhere, and as usual I wasn’t able to wind it up. My work, if it’s going well, tends to diverge instead of converge, which is frustrating because it means I don’t have a success model that involves a short form. I’m still trying to figure that out.

So, this thing that I imagined being a short story was suddenly 40 pages long. And then it was 60 pages long. And then 80 pages long. That was the point at which I put it aside for a while because my assumption was that I just didn’t know how to resolve the situation that I was describing. And then it came to me that I didn’t actually want to resolve the plot in the way that I expected. And, you know, I stumbled on another voice, and the other voice worked really well. The other voice was really compelling to me, and seemed to know more about what was going on than I did.

And that voice was Karen.

Yeah, the voice of this character, Karen, who comes in and says “My name isn’t and never was Karen, but I’ll be Karen.”

I wasn’t thinking that hard about Trust Exercise, because it started as a distraction from the other project. I was really banging my head against the wall about the other project. And I do think that sometimes when you’re not actively trying to solve a problem, an interesting solution will present itself.

Karen’s section emerged so organically. I’ve always hated it when other writers say this, but it wrote itself. It really was this narrative that—almost from the minute that I started it—everything that was happening with her was clear to me, and I knew where we were going to end up. It was really exciting. I never write that way, but I knew it wasn’t the end of the book. And so once the really great momentum of completing that section had played out, I hit the wall even harder because I was like, now I still have to finish this.

It was a process of intuition, coupled with total stubbornness. At that time I decided it was a three-part structure. I wrote so many endings for this book. The ending that is presented to you is the fourth ending, there were three previous ways in which the book ended. Maybe they’ll go into my archives. They’re very different, they’re like alternate universes.

How did you choose this unnamed Southern town in the 1980s, and the performing arts school in particular, as the setting for the novel?

I attended a performing arts high school growing up, and I grew up outside of the Northeastern metropolitan region that I’ve now lived in for more than twenty years. When I first started writing the story my mind went back to the place that I went to school and the experiences that I had, and then invention begins almost immediately. Most of my books have something in them that is borrowed from my experience and then pretty heavily embroidered.

I went to a school that is the sunny-side up version of this school. I had a great time there, I still treasure friendships that were made there, I had wonderful teachers. The darkness and the sadness and all of the disconnected pain that a lot of these characters experience is a better story.

For about two seconds I wanted to be an actress, and I did seek out a theater program. It’s such a funny thing to contemplate. I was so self conscious, it was just not my forte at all and for years I thought of it as this weird blip. But I think my little flirtation with the theater meant much more to me than I may have realized, because I really wanted to find my way back into that world, for all of the great things that it contained, especially collaboration and making art with other people, which is something I really miss as a writer.

I missed the theater so much but then there was also the underside to it: insecurity and anxiety and the desperate desire to be accepted and singled out. The book ends up delving really deeply into that emotional terrain.

There’s this really memorable scene where teenage Sarah is crying in the bathroom, and her teacher comes to her and tells her that these years of her life are so important because she has this heightened experience of emotional pain, which is a great gift that will inform her creative work as an actor. But Sarah doesn’t go on to become an actress. She goes on to become a writer.

Yeah, exactly, which is the path that I’m more familiar with. And that idea that your experience at that age for some reason is going to carry a higher currency for the rest of your life was really interesting to me. There are studies about this that I’ve always been fascinated by—how people never really get over the musical preferences that they form in their adolescence. We form these bonds, not just with people, but with ideas or art or music when we’re kids that end up being so much more influential throughout our entire lives than ideas that we acquire later.

That [idea] was part of where [that scene] came from—a teacher saying to her, this feels horrible but you know you’ll never feel this horrible again and there’s something valuable in that. You’re going to have those rough edges sanded away by experience and that’s a loss.

I was reminded of Regina in My Education and the conversations she would have with Martha.

You’re identifying themes that are clearly still exercising a hold over me, because you’re absolutely right. Regina was for me most compelling as a study in youth, and the difference between youth and all those periods of your life after youth, which I don’t want to call age. I’m closing out my fifth decade of life, which is amazing to me. But when I was in my early twenties I was an adult. I was independent, I made my own decisions, I supported myself. I thought of myself as being very mature. But a couple decades later, looking back on my own early twenties, I was like, oh my god. That was part of what My Education was about for me, how adulthood is a kind of childhood, and you leave these versions of yourself behind, and then try to figure out what that person was thinking.

You mentioned that opening scene of the novel in which the students are crawling around in the dark, which is also a scene I noticed that appears in American Woman.

It is. It’s almost a backwards easter egg. I guess I have this low estimation of my own work, because I mentioned this to a really good friend of mine who reads all my drafts and I said, I did a scene that’s really similar to that scene in American Woman but no one will remember that. She was like, yeaah [skeptically]. It is really the same scene and they originated in the same place, out of my brief experience of acting school. So yeah, I recycled it [laughs].

I found it so interesting, because ego reconstruction—the exercises of self-examination through which you can supposedly gain control of your ego—is present in both books. When one of those exercises, the repetition exercise, is moved from the context of an underground anti-government cadre to the context of a theater school, it really underscores the element of control in the school setting, especially for a teenager.

One of the things that I was so fascinated by when thinking my way back to acting class is the repetition exercise, which is a classic acting exercise. Those repetition exercises have in the real world made their ways into all sorts of strange places, including organizations like the Church of Scientology, which are deeply engaged in what some people might call brainwashing. So when I was trying to think about how this revolutionary cadre would conduct themselves, it wasn’t a stretch to think about them doing these sorts of exercises because I knew that they were also adapted by L. Ron Hubbard for his purposes. I’m sure they show up in a lot of other contexts in which social control is a goal.

You talked about how the novel unfolded. I’m curious about how you came to the uniting thread of the stories of women who are placed in situations where there are blurry lines of consent.

One of the things I kept thinking about was how when you’re a student, you often feel yourself disempowered, but you often don’t see your lack of power quite as clearly as you might be able to later, when reflecting back. There have and continue to be so many belated examinations of abuse in educational contexts. That’s a thread that I followed as a parent and as a teacher for years and years and years. One story after another.

It’s become this drearily familiar story of adults coming forward years after they were students and saying, something happened between me and an older person that I either wasn’t able to recognize as having been abusive, or wasn’t able to name as having been abusive. But now I’m ready to say this happened. And, you know, this is Spotlight, the story of what’s happened in the church. It’s the story of what happened at the Horace Mann school here in New York, and in so many other places. These stories have always really riveted my attention from long before I was writing this [novel].

That student-teacher abusive relationship can take place between a student and a teacher of any gender, but there are so many stories of male teachers and female students that I think that thread started to predominate in my exploration of this particular, seemingly incurable social and cultural problem we have.

It’s connected to all of the debates that we’re having now about agency and consent, and these really difficult and important schisms in feminist thinking between the idea of needing more institutional protections, and wanting to push back against the possibility that [those protections are] really paternalistic and infantilizing. There’s no easy answer. But I think one of the reasons I find teenagers so interesting—apart from the fact that I now actually have one as a parent—is that they are mature people with agency but at the same time, they’re also children. They do require guidance and protection, and they can be exploited by the very people that they’re presenting themselves to as mature adults, which are often their teachers. It’s a very difficult landscape for us to figure out, and the landscape is changing constantly.

Trust Exercise is your fifth novel. Could you talk about why you have continued to return to the novel as a form?

The novel form continues to really attract me it because it’s so flexible. It just seems accommodating of more than we’ve even thought of yet. I think the novel still feels like it offers a lot of freedom. Also, as I’ve mentioned, I can’t seem to be concise, ever, and novels are longer than these other [forms].

I have a question that comes out of my own curiosity as someone who works for AAWW. I’m interested in hearing about the experience of your winning the Asian American Literary Award in 1999 for your debut novel and what that meant to you as an emerging writer at the time.

It was incredibly meaningful to me. And at the same time I think that when I was first emerging, and when that first book came out, I also had all this worry about labeling. This is a conversation that we had as a community more often in the past than we have it now. I think now it’s like, What were we so worried about? At the time, in the 90s, I was part of a lot of concerned conversations about whether we embrace these labels, which feel like they’re setting us apart from mainstream writing and signaling to readers, you can pass on this. There was a lot of that conversation. Looking back now, it makes me laugh internally that that would have made me anxious. We have much bigger problems in the world.

It’s a very nostalgic memory for me that also shakes me because it was twenty-one years ago that [The Foreign Student] came out. That’s wonderful and horrifying at the same time. At the time it was gratifying, and I think that it also feels like a long time ago because that category has become so capacious.