Notes for a hypothetical interview with the author re: Taipei, living in the present, memory, moral responsibility, technology, zen, etc.

September 24, 2013

Dear Tao,

Thanks for agreeing to be interviewed! I’m really looking forward to the conversation! Do you think we should have a few rounds of back and forths?

I still remember the day I picked up your books. I’d just graduated from Berkeley—it was 2007, the year Melville House published Eeeee Eee Eeee and Bed—and I was trying to become a writer. Like I often did at the time, because I didn’t have enough money to buy new books, I was reading Miranda July’s No One Belongs Here More Than You while standing up in Pegasus Books. When I noticed that she had blurbed Eeeee, I read the first few pages and was drawn to it immediately.

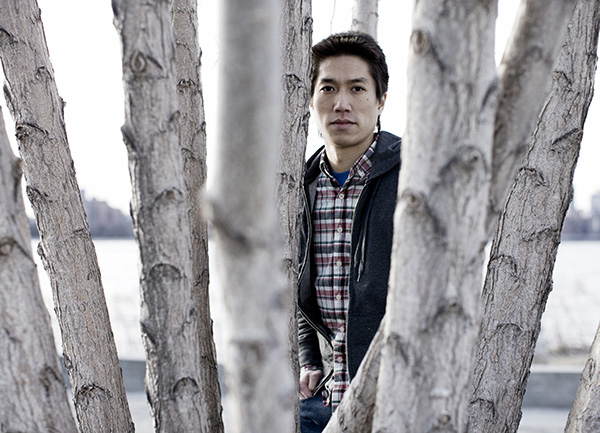

Blake Butler writes that your new novel Taipei is “a work of vision so relentless it forces most any reader to respond.” Dwight Garner writes in his New York Times review that he hates when reviewers say they love/hate a book, yet he also loves/hates Taipei. Ben Lerner said that “liking” or not liking your writing is totally beside the point. Your work, like life, puts us in the uncomfortable position of having to figure it out.

All this to say—I’m super grateful for this opportunity to talk to you about some of these long-held questions of mine. I’m sorry this email is so long–my commentary in this whole exchange will eventually be cut by at least 98%.

Extremely eager to read your responses!

Best, Anelise

+ + +

“PRESENCE”

Q: Does Paul—the young novelist-protagonist in Taipei—truly believe in the self-helpy mantra that happiness is living in the present?

At the start of the book, Paul thinks he should learn how to be more present, having deduced from philosophy and popular culture that living in the present is the key to happiness. Unlike surfers and chefs, for example, who describe being focused and “at one” with the task at hand, for Paul and his friends, existence feels fractured and directionless:

“We had a specific goal, I remember,” said Paul. “What was it?”

“I don’t know,” said Daniel after a few seconds.

“We were just talking about it.”

“I remember something,” said Daniel absently.

“Oh yeah, selling books,” said Paul.

“Let’s do that,” said Daniel.

“We just actually forgot our purpose, then regained it,” said Paul grinning.

“We still kept moving at the same speed, when we had no goal.”

Essentially Paul has lived a long time moving at the same speed as a person with a goal, while having no real goal. During the “interim period” before his book tour, Paul begins to wake up without his memory, and feels he has to unzip a file in order to reacquaint himself with his context. At first his memory loss is distressing, but after upping his drug intake, Paul realizes he might have finally attained what he calls a “form of Zen.” Without a memory, he no longer has any desire because he forgets right away what it was he wanted.

At the end of the book, however, Paul seems to reverse his opinion about living in the present. Far from pleasurable, the mushroom-induced finale at the end of the book suggests that an experience of pure presence is not unlike dying. Paul believes his only shot at life is to “[remember] some of what had happened with a degree of chronology sufficient to re-enter the shape of his life.” Which is to say that to lose access to your past and projected future is to become like the stereotypical ghost who’s unaware they’re dead, and keeps repeating the same gestures over and over again. (Think Nicole Kidman as ghost.)

“TECHNOLOGY”

Q: Are Paul and his friends already ghosts, though?

In a way, Paul’s already living in a permanent present, as digital memory has slowly supplanted his actual physical memory. Even if he isn’t “present” in the moment, he always manages to be present in a virtual reality. For example, Paul and his wife Erin can only interact if they are being mediated by an extra layer of technology. They argue via email as they sit on opposite sides of the bed; they film themselves having fun instead of just having fun; they imagine interiority as a constant stream of visual/verbal commentary running alongside lived experience. Many wouldn’t call this living in the present, but since technology automatically preserves all of this activity and timelines it, Paul always has a memory that he can “check.” For example, he only remembers forgetting the night he was “depressed at dinner w Michelle in empty house / while driving to Pittsburgh w Erin asleep / Typed on iPhone in Gmail w right hand / Listening to P.S. Eliot / Left hand on steering wheel” because he emailed the notes to himself.

Q: Are they glad they’ve lost their physical memories?

At one point in the book, Paul thinks “this is hell,” as though he and his friends are all trapped in a fugue state. And yet, their behavior doesn’t change; they keep doing the things that cause them to feel like hell.

“MEMORY”

Q: Does having constant access to a digital memory cause Paul and his friends to feel always already derivative?

Towards the beginning of their courtship, Paul, on mushrooms, is self-consciously mumbling to Erin about UFOs when Erin shares a detail about how she used to wear purple and glitter so that aliens would recognize her as one of their own. At first Paul is moved by this detail in a genuine way, but immediately he begins to sense that this UFO/purple/glitter thing has already been shared somewhere else. He asks her if she’s blogged it before. When she admits that she has shared it before, Paul is hugely disappointed—it’s as though his moment of genuine surprise and connection is actually already derivative. If everything is archived, then literally everything has already happened before, or very possibly could. This must contribute to Paul’s sense of hopelessness, right? If nothing is new, then nothing is worth doing.

Q: Is this feeling of being always already derivative the reason why everything has to be expressed in scare quotes?

I’m really interested in stories about how people who lose their short term memories can still be perfectly happy and oblivious, while people who have deja veçu—a disorder that causes them to experience waking life as something that’s already happened—will simply refuse to do anything. They even refuse to watch TV because they insist that they’ve seen it all before. I wonder a lot of the time if the Internet makes us all sufferers of deja veçu. We are amassing this infinite and expanding archive of retrievable information, and with this comes a huge sense of inevitability, hence boredom. Isn’t this what is happening to Paul during that purple UFO glitter exchange?

“LIVING vs EXISTING”

Q: Or, would you differentiate between “living” [thriving purposefulness] “being alive” [the physiological state] and “existing” [enduring through time]? If we “live” [stay alive] only in order to feed our experience into a computer, then conceivably we could “exist” forever, though there’s no heartbeat. Whereas to lose your chronology, to be in the pure present, you’d get the feeling of never having “existed” but nevertheless still be “alive,” “living.”

Another way to put it is that to be “present” also means “to exist.” When we do a roll call, we raise our hands and say “Present!” “I’m here!” “I exist!” Is your definition of living in the present closer to “I exist!” than the common idea of oneness and flow?

Q: The Internet seems like a place that allows us to do both at once—to exist and also be interconnected as one. But if that’s the case…is being human (as opposed to machine) simply another obstacle we have to get over?

Q: The Internet seems like a place that allows us to do both at once—to exist and also be interconnected as one. But if that’s the case…is being human (as opposed to machine) simply another obstacle we have to get over?

In your Fader interview, you say that everything in the universe will eventually be processed into computerized matter, and soon we’ll all be in this interconnected web, the “www” but way larger, universal. No humans, only computers. In your book it’s obvious that the virtual has already made the leap into the physical, “actual” world. The process is already happening. Paul imagines himself as a dot hovering in a realm that seems a lot like 3D Google Earth. And in lieu of sharing how he feels about getting married to Erin in Las Vegas, Paul imagines a common expression of Gchat frustration scrolling over the desert landscape…

?wpkjgifhtetiukgcnlm

Q: How do you feel about this leap from the physical into the virtual? Does the leap give you discomfort or hope?

Because I guess to be human is to be mortal and die, to fall into moods that we don’t like, to lose control; whereas to be computerized is always to be in control and possibly exist forever as a Facebook timeline or Wikipedia page or Twitter feed. Towards the end of the book, Paul and his friends all decide to livetweet the X-Men movie and Paul says to Calvin: “You should tweet it, stop talking about it,” implying that tweeting is preferable to speech, because speech evaporates on impact. And even as Paul and his friends are throwing up in the bathroom or quivering in some dark corner of the theater, they still have the ability to communicate with each other through those tweets. I think their insistence on tweeting is a freakish form of control they’re exerting over themselves that surpasses the actual physical discomfort that they’re feeling. Is this an example of them using the technology or being used by the technology?

“DRUGS”

Q: Do drugs make you more present or less present?

Drugs are also a kind of technology, like a hammer or boat. Heidegger says that in order to resist what he calls the “technological clearing”—where things show up for us and present themselves as meaningful and valuable by being fast, efficient, or useful—we must be as inefficient as possible. In order to step out of a technological understanding of the world, we have to stop thinking about means and ends. So the use of drugs makes me think of Heidegger because Paul and his friends have begun to use and control their own bodies in the same way that one would control a robot. They use uppers to be fun and engaged and productive, and downers to go to sleep. They can will themselves to have an experience with MDMA and LSD. Is the ability to use your own body in this way good or bad?

“BOREDOM”

Q: What is boredom? Does boredom scare you?

“MORALITY”

Q: Do you think morality, along with humanness, is an outdated concept?

Q: Do you think morality, along with humanness, is an outdated concept?

In your book, shoplifting’s okay and so’s doing drugs, but meat and sugar are not okay. Is “morality” in this fictional universe something that just gets decided along the way? Or is even the idea of morality irrelevant?

Q: Alternately, do you feel any sense of moral responsibility towards your readers?

For example, you are often compared with Bret Easton Ellis, whom David Foster Wallace hated because he said that all American Psycho was doing was showing us how fucked up everything was but not giving us any hope beyond our fuckedupness. Even if DFW was a nihilist, he was still trying his very best not to be one.

Obviously your books avoid moralizing and judging and pathologizing, but how do you feel as an artist? Do you ever think something like: I can’t make my readers too depressed or show things that are too ugly b/c it will just disturb them? Because it’s the artist’s responsibility to offer “hope”? Do artists have responsibilities like that?

Sorry about how long this is—I know this is a lot of material—but your book just gives me a lot of ideas!

Hope to hear from you soon,

Anelise

+ + +

Hi Anelise,

Sorry for the delay. I will pass, but thank you for the continued interest. I just really have nothing to say! And am “swamped.” And you have a lot to say, so it makes sense to me to pass, really does…thank you however and sorry for the inconvenience.

Tao