Looking back at 9/11 and the Fall 2011 issue of the Asian American Literary Review

September 27, 2021

Ten years ago, Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis and Gerald Maa, the editors of the Asian American Literary Review at the time, invited Rajini Srikanth and Parag Rajendra Khandhar to guest-edit an issue of the review marking the 10th anniversary of 9/11. “We felt that this was an Asian American moment and we want to commemorate it,” Parag recalls Lawrence and Gerald saying. The resulting volume, released in the fall of 2011, gathers the testimonies, dialogues, essays, and art of more than 70 artists, organizers, lawyers, educators, and more. Their words filled in the gaps of official acts of mourning, and brought alive the struggles and resistance of Muslim, SWANA, and South Asian communities in the days, months, and years after September 11.

I came across the issue on the reading room shelves at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop several years ago, but I only sat down to read it in its entirety earlier this year. As we approached the 20th anniversary of September 11, I wondered what the generation born around or just after September 11 would come to know of special registration, a precursor to Trump’s Muslim Ban; how they might hear of the organizing efforts of DRUM (Desis Rising Up and Moving) to advocate on behalf of those detained and deported without cause; whether they’d have a chance to listen to the spoken word artists who spoke so directly to both the tragedy of that day as well as the horror of the United States’ Global War on Terror. In the AALR issue, Rajini and Parag collected so many testimonies and works of art that tremble with continued relevance. And so I invited them to revisit the issue with me. “Commemorations cannot be static affairs,” Rajini writes in her introduction—our hope is to continue unsettling the ground, and to set the AALR issue into motion. We are making the issue available to our readers for free via a PDF.

Rajini and Parag joined me for a Zoom conversation in late August. Rajini, who has published multiple scholarly works and coedited several anthologies of Asian writing, joined from Boston, where she serves as dean of faculty and a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Parag, who has worked in many Asian American cultural and organizing spaces and now practices solidarity economies and community economic development law as a principal at Gilmore Khandhar, joined from Takoma Park, Maryland. The two of them have also played a significant part in the history of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year: Rajini coedited one of the Workshop’s first anthologies, Contours of the Heart: South Asians Map North-America, and Parag served as a program director in the nineties. It was my pleasure to bring them back into conversation with the Workshop and reflect on the Fall 2011 issue of AALR, the importance of collectively documenting Asian American history, and the possibilities of solidarity work.

—Jyothi Natarajan

Jyothi Natarajan

It has been a real privilege to spend time with this Fall 2011 issue of the Asian American Literary Review that you coedited. I was astounded to see how many different perspectives you had pulled through in this issue—the organizers and activists and lawyers and artists, students, young people.

I wanted to start with a question around the nature of visibility and erasure. Rajini, you write in the introduction about how quickly we can forget our community’s milestone moments of political awakening, and you talk about the murder of Vincent Chin, and the ways in which the re-remembering of his murder keeps taking place, generation after generation.

Parag, in the afterword, you asked this question that’s really haunted me: “Will future generations know whom to ask or where to unearth the undocumented histories of our communities?”

Throughout the issue, it’s as if you both have been guarding against a kind of erasure that you can anticipate. Can you two reflect on the nature of visibility and erasure of community history, starting 20 years ago, and then maybe 10 years ago, and today?

Rajini Srikanth

When you talk about the two poles of visibility and erasure, for a strange reason Mahmoud Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness comes to my mind, which is about the 1982 bombing of Beirut. That particular title had always struck me as powerfully, paradoxically compelling—that on the one hand you have to remember, but on the other hand, remembering is so painful that sometimes you forget, or you want to forget. I know that’s not what Darwish intended—he was asserting the power of language and memory in the face of forgetfulness. There’s so much to remember from 20 years ago that is too painful to resurrect, and yet not resurrecting it means you forget about those crucial moments of resistance, of solidarity, of support, of fighting, and of demanding some kind of accountability.

So, while 2001 thrust us into the forefront—and when I say us, I mean in this particular instance the marginalized Asian Americans, Sikh Americans, Muslim Americans—in that moment of being made visible—as suspect, as terrorist—our pain at our own losses was also being erased by the official discourse. Samina Najmi talks about this in her piece; she writes: “Two months after September 11, 2001, I spoke of being robbed of my right to grieve, of my feelings of homelessness in the backlash against the likes of me, a Muslim-bred Pakistani woman who called the U.S. home.”

I’ve just been struck by how those instances that make communities hyper-visible in not a positive way also have woven into that hyper-visibility the erasure of their pain and their trauma by the state because their loss, their pain, is not recognized as legitimate.

Parag Rajendra Khandhar

I’ve really been struck by the informal ways in which our community histories are passed, from generation to generation, from nonprofit worker to nonprofit worker, from person in an apartment building to the next family that comes into that apartment building. I’m thinking especially about refugees getting resettled into the same buildings, and that there are these different layers or strata of knowing. So when aspects of our community are visible, I want to ask: Is it a monolith? Is it one narrative? When is the time to complicate that narrative? What purpose does that serve? Where are those alternative narratives really vital?

I think of Zohra Saed’s piece from the issue, where she describes feeling like she was supposed to play this role as an Afghan woman, and then as a coeditor with Sahar Muradi of this forthcoming manuscript of Afghan American writing that they kept being told was not going to sell. Zohra writes about searching for a publisher “that would work with us rather than work to mold us into its image.”

I saw so many places where people were trying to visibilize their stories and communities in these different ways. I feel a commitment to that. And I actually feel that commitment currently, as I’m in so-called Solidarity Economy spaces, which I think are beautiful, but where it’s very easy for Asian Americans, or South Asian Americans or whomever, to be reduced to a certain model minority role. That’s where I feel like, okay, maybe I can share some stories and alternative narratives.

RS

With all of the protests following the murder of George Floyd, the nation erupting in righteous outrage, and the fact that Black and brown communities have been the hardest hit by COVID, there was a lot of conversation on our campus about paying attention to our students of color—a good number of the students are Asian American, and there’s a very large Latinx population, a very large Black population. So there’s definitely been a lot of concern in the last 18 months about the impact on our students’ communities, especially Black communities and Latinx communities. However, in these conversations, Asian Americans just kept getting elided. And this was before the March tragedy in Atlanta. I remember one of my colleagues saying: “I’m an Asian American here, and I haven’t heard a single thing about Asian Americans and how they’re surviving or enduring this pandemic. Are we people of color or not?” And of course the irony of that was, within a few weeks there was this horrific, horrific tragedy in Atlanta forcing everybody to once again say, “You can’t erase this community because it’s woven into the racialized history and landscape of this country. And what happens to us erupts when least expected.”

How do we keep ourselves in the conversation as part of the fabric of this country when there is no crisis? Who, in a moment of trauma, gets pushed to the foreground? How are we ever made an integral part of the conversation, an integral part of the consideration for how we build a society in this country?

JN

Where were you in your lives when you came together with the Asian American Literary Review to organize this issue? And what had you been doing in the previous 10 years just after 9/11? What was your relationship to Asian American, South Asian, Arab, Muslim communities?

PRK

Thank you for this question. Previous to September 11, I was working in New York City in and with Asian American communities. I started at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and then I worked with the Asian American Arts Alliance for some time, and then eventually found myself at the Asian American Federation. I was doing census advocacy there, because the 2000 census was coming, and I was working with folks at the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) and others who were doing redistricting work.

I lived in the Hudson Valley at that time and worked in Lower Manhattan, so I usually passed through the World Trade Center in the morning. But that morning of September 11, there was a primary going on, which Anouska [Cheddie] wrote about. And so I was doing Asian American exit surveys and voter protection with AALDEF way out in Eastern Queens. I remember my first time traveling into Manhattan a few days later was actually into a satellite office of AALDEF where the attorneys were immediately thinking: Is the ruling in Korematsu v. U.S. still valid? They were thinking that way a day or two in. They were thinking immediately—what is this going to mean, what’s going to happen. And they had called a community meeting in that office, and people were scrambling, people were trying to figure out what to do. I remember one of my coworkers, Shazia, was organizing interpreters to be at Ground Zero and at the FEMA sites to ensure that Asian Americans received some kind of language access.

The Federation was an intermediary that worked with social service agencies. We started to think through what kind of relief program would be necessary, and then what kinds of recovery and advocacy would be useful. So there was some collective fundraising and work with agencies out in different parts of the city.

I worked on post-September 11 issues for about three, maybe four years directly. And at the same time my partner at the time, Deepa Iyer, was starting SAALT, South Asian Americans Leading Together. They were doing this work every day. The calls were coming in, and they were monitoring hate crimes and trying to engage the federal agencies and local groups that were doing so much work on the frontlines everywhere.

For me, I was in an intermediary role, so I was hearing about so many things and seeing community members through direct service and advocacy work. But in just speaking with any of the groups, any of the organizers, I could see how it was nonstop—they were working all the time.

When the idea for this AALR issue came around, I was at the Asian Pacific American Legal Resource Center. I had gone to law school in D.C. and was working as a tenant’s lawyer in the D.C. area with Asian American tenants and others who were organizing. I had actually worked with the Asian American Literary Review to help them separate from their university connection. So I knew Lawrence and Gerald, the editors, and it was their idea. They said, “We were having a conversation, we knew the 10-year anniversary [of 9/11] was coming, and we felt that this was an Asian American moment and we want to commemorate it.” With where I was in my trajectory in Asian America—where my heart was so in Asian America, but I was getting more and more disillusioned—to feel like Lawrence and Gerald got it, you know, it felt like I needed that. And then to know that Rajini was going to be part of it was like, oh, this is gonna be amazing. It felt like I had enough space and time between all the things that were happening daily to really take stock.

RS

One can begin at so many different points, and the trajectories can take very different arcs. But I will say that I was just incredibly fortunate in 1994, almost serendipitously, to become really close friends with Sunaina Maira. Sunaina and I lived next to each other in this suburb of Boston. I sort of stumbled onto her, she stumbled onto me, and I don’t I know—there are those friendships and relationships that you have no idea are going to be so generative and so long and so rich.

Through Sunaina, I got drawn into some real on-the-ground activist work and met a number of people: Vijay Prashad, Amitava Kumar, Raju Sivasankaran. It was several years of being with young people, people who were a good 10 or 15 years younger than I was, and just admiring their resolve, their energy, their refusal to let things be the way they were. I appreciate it so much. I couldn’t have asked for a better education, if you will. I’d always been a bit of a radical anyway, but these friendships brought out the radical in me again.

I applied to UMass Boston when an opening came up in the English Department in 1997. I got the job in 1998, and that campus has really shaped who I have become. It’s a working-class, immigrant- and student of color–focused, commuter campus. I occupied these multiple positions in the English department, in the Teaching Licensure program, and in the Asian American Studies program. I had multiple homes and multiple mentors, and it shaped who I was. I think that whole experience led to Contours of the Heart with Sunaina, because we wanted to put South Asians on the map. Almost on the heels of that came A Part, Yet Apart with Lavina Dhingra Shankar, who was at the time at Tufts. That became another work we didn’t realize would have such an impact—clearly there was a need for it.

I was also getting to know people on my campus like Paul Watanabe, Peter Kiang, Karen Suyemoto, and Shirley Tang. And I was learning about the whole Vietnamese American experience, because we have a very big Vietnamese American student population, students who are the children of refugees who came over in 1975. I was educating myself on the complexities of Asian America.

So when 2001 happened, it felt like everything was coming together to help me understand what I needed to do. I’m in a place I love and with people I love, and at a campus that means so much to me. I’m learning so much about traumatic moments in Asian American history, and then suddenly 2001 happens. Maybe a week after the attacks on September 11, I was at a conference at MIT during which Japanese Americans came forward in an auditorium and said, “We’re here for you, Arab Americans, Muslim Americans. We’re here for you.” It felt very similar to what was happening in your circles, Parag, trying to figure out to what extent we can make sure there is not another incarceration. It was such a powerful moment, such a public moment of declaration of solidarity and support. It was so powerful to see Japanese Americans coming forward and saying to Arab and Muslim Americans, “Don’t let what happened to us happen to you. And we’re gonna stand beside you and make sure it doesn’t.”

“How do we keep ourselves in the conversation as part of the fabric of this country when there is no crisis? Who, in a moment of trauma, gets pushed to the foreground?”

Rajini Srikanth

So in 2010, when Lawrence and Gerald approached us, I had spent 10 years really steeping myself in South African history and politics. I had gotten involved with a helter-skelter hodgepodge group on the UMass Boston campus called the Human Rights Working Group, where one could challenge all of those establishment narratives about human rights and yet be committed to the idea of human rights.

I had published The World Next Door, which is like an overview of South Asian American literature. And as a result of my having been mobilized, if you will, by the ways in which South Asian American, Arab American, and Muslim American communities had been targeted and profiled right after 2001, I had become very interested in what was happening at Guantánamo Bay. Several corporate lawyers, who were all making $500 an hour, became interested in the detainees in Guantánamo Bay. Initially their interest was not for any empathetic reason, but more because they believed so strongly in the Constitution. They were thinking, “This ‘sacred’ text that we work with is being maligned and violated.” So they went to the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) in New York, an extraordinary organization founded during the Civil Rights Movement, and CCR challenged Bush and Rumsfeld from day one, when they declared the Global War on Terror and decided to open Guantánamo Bay. I started talking with the CCR lawyers as well as the lawyers from the private bar and began writing the book Constructing the Enemy: Empathy/Antipathy in U.S. Literature and Law. Anant Raut, who contributed to the special AALR issue, was one of the lawyers from the private bar.

When Gerald and Lawrence called me, I was like, yes, I know what’s going to happen on the 10th anniversary—there’s going to be nationalistic fervor, in which, of course there are going to be appropriate remembrances, but there’s also going to be this huge, huge, huge gap. No one’s going to talk about the ways in which South Asian, Muslim, Arab communities have been decimated, devastated, destroyed, and literally pulverized, where people are trying to rebuild their lives because partners have been sent away, people have been deported and detained.

JN

What do you remember about your hopes for organizing this issue at the time that you were working together? What drew you to the work?

RS

The hope was, for me, that I would have the courage to say the things I wanted to say and that people would understand why those things needed to be said. I now have to say, my colleagues on my campus were amazing. The biggest gratification was when 200 students showed up at the launch of this issue. Many of my friends are in this issue. Parag, so many of your friends are in this issue, and then there’s an overlap, because we know a lot of the same people. So my hope was to reach out to people that mattered a lot to me, who had helped to make me the person I am, the scholar I am. But also, the activist I am. My hope was that I could pay homage to those who had helped shape me, because I take no credit for who I am today—it’s my campus and my friends and my colleagues, and all of the young people in my life, you included, Parag, that I’m incredibly grateful to. And that hope, I feel, was realized.

PRK

I’m really loving that I’m called young in this context.

Rajini, you had said something early on that I made a note about—the notion of how erasure happens in our own memories, and that it’s pretty much a function of trauma. Even though I didn’t have the language at the time—it’s really now as I’m studying more around trauma and around healing around where trauma actually lives—I realized that what I felt intuitively was that so many of these amazing people, whether they had continued to do similar work or they’d moved from it, were holding a lot. They were holding these collective memories; they were holding so many stories. So on one level, I wanted for the people that I love and care about to be able to release a little bit, and that maybe this would be cathartic and part of a process in some way.

Another hope was that I knew that there are people in movements that folks know and name, and then there’s a lot of other people. I had the benefit of not being so in it, and also being in touch with a lot of people. If you read the issue carefully, you see people naming people who aren’t in the issue, whose names just aren’t popular—they haven’t run a bunch of organizations or written a bunch of things. I was struck by that. So many people are carrying names of people who have stories. My hope was to bring some of that in. And if the whole issue were that, it still wouldn’t be enough. We still wouldn’t be able to capture all the different stories and all the different perspectives.

I think the way that this turned out, where you have people looking at it from a number of different perspectives, fulfilled my hope for what this could be more than if it were just my vision, so to speak, of what this could be.

I feel like it fulfilled that part of the hope, and it also left me wanting to continue to do this work and left me really grateful for community archivists and people who are doing this work really intentionally as things are happening. Which is super hard.

RS

We were so focused on finding people who we wanted to contribute to the issue that now when I think about it, I see just how extraordinary it was of Lawrence and Gerald to imagine and envision this issue. It was an affirmation of what had happened to our communities, and I am just deeply, deeply grateful to them for that. Because it was almost as though they were providing that different Asian American narrative to the one in which we had always been marginalized and erased.

PRK

Lawrence and Gerald had infinite patience with me. It took me so long to get that Subhash Kateel interview. I was trying so hard to get Subhash and Aarti Shahani together to speak about Families for Freedom. I had to accept that it just wasn’t going to happen in time for this issue. And so the only way I could do it was when Subhash was literally here [in D.C.], and we went around Silver Spring and we ate, and we drank, and we talked, and I had my phone or whatever. And then Gerald hand-transcribed that. There was so much love and so much care. AALR looks like a traditional literary journal, but everything before had really focused on creative work, poetry, prose, and maybe book reviews. But for them to take this departure and to have personal testimony—it really felt like they took a leap, and they trusted us.

JN

What has the experience been like to dip back into the issue? Did you want to draw attention to any piece in particular?

And I also wanted to ask about the process of working with some of these writers. As I was reading through the issue, it’s really remarkable to see this combination of writing by and with people working as activists in the organizing space, folks who were immigration lawyers, people doing direct service work, artists, and in some cases people who might not have thought of themselves as writers before this.

PRK

Looking back and actually spending time with the issue in this way was really powerful. I have it on the shelf and I have the PDF, and I’d look at different pieces here and there, but to really actually spend time with the whole issue was very powerful. I came to appreciate that there were moments of real vulnerability here, there was contention, there were contradictions, some people talking about poetry being useless when there’s a lot of poetry in here. That whole dialogue on the relevance of literature was really striking for me to read. And even just reading educators talk about how they were engaging with September 11. I feel grateful to have had this opportunity to read it in this way because it was like a mission. I want to read this. And some of it is actually really difficult to read.

RS

It’s interesting how we both sought out our contributors from the networks that were most familiar to us. A lot of the people that I reached out to were my educator friends and my activist youth friends, for example, Mazen Naous, whose essay is about the need for Arab American literature. I was happy that we had at that time thought it important to devote some space to why Arab American literature is important and how it helps us understand the complexity of the Arab American experience. And then seeing Magid Shihade’s essay. Magid, who is Palestinian, was at the time living in the U.S., and now he’s back in Birzeit in Palestine. It reminded me that we were thinking of linkages—we were not trying to keep this isolated as a U.S. tragedy and its aftermath, but we were looking at it as this arc of imperial U.S. power as it gets played out in different ways in different parts of the world.

I smiled when I read certain conversations, and I thought to myself, those voices haven’t changed. Especially reading Rakhshanda Saleem and Sunaina Maira. Just the vision, the critique, the complexity, their drawing attention to what is rupture. I was just so struck by what Rakhshi (Rakhshanda) said: The kind of rupture I want to see is a rupture in the discourse of vengeance and hostility. The rupture is not that suddenly the U.S. finds itself victimized, but the rupture has to be a change in how we think about the long arc of history.

Sunaina drew attention to September 11 and Chile, which nobody ever talks about. The day the U.S. bombed Chile and overthrew a democratically elected Allende to put in place General Pinochet as the dictator. I was reminded of how prescient some of our contributors were, in their ability to see the long arc of history and to underscore how we can never disentangle domestic policy from foreign policy, how we always have to see them in combination.

The other thing that I loved was going back to read Samina Najmi’s piece. Samina is a dear friend who has since that time become this really accomplished creative writer who has published beautiful pieces about being Pakistani American, about her experience growing up in Pakistan, about what it’s like to raise two children in this country now. So, going back and looking at these pieces told me that what some of the contributors were saying 10 years ago even today holds, and it holds in very powerful ways. They underscore for us the nexus between the kind of nation that the United States chooses to be on the global stage and what happens at home. Like, what is incarceration, domestically, what is the Kandahar Airfield and Bagram prison in Afghanistan, what is Guantánamo Bay—they’re all of the same piece. These writers help us see those connections. The portrait they provide us is not a happy one, but it’s one that we all need to be very, very aware of.

The other thing that struck me in the issue, in addition to Rakhshanda saying there’s got to be a rupture in this nationalistic discourse, was DJ Rekha’s very beautiful last lines [in her piece about deciding to hold her monthly Basement Bhangra party in Manhattan nine days after September 11]: “You do open because sometimes a party is not just a party. It’s also a community space.” And I so love that, because she really must have been asking herself, “Do I hold this event so soon after 9/11? How is it going to be read, how is it going to be processed? Is it safe for us to come together?” I felt her own concerns and anxieties as she was talking herself through that, and then I love the way she ends it. Yeah, it’s a party but we needed one. This book is like a party in some ways.

“So many of these amazing people, whether they had continued to do similar work or they’d moved on from it, were holding a lot. They were holding these collective memories; they were holding so many stories. So on one level, I wanted for the people that I love and care about to be able to release a little bit.”

Parag Rajendra Khandhar

PRK

I really appreciate that, too. Rekha was very, very resistant to writing anything. It was a lot of back and forth, and then I met up with Rekha before she deejayed a Basement Bhangra here in D.C., and I was like, “Your voice is important in this.” For a number of the people it was like that, for people who didn’t consider themselves writers. There were definitely a number of people who I actually pursued, trying to get something from them, and it didn’t work out. They said, “I’m going to try.” And they just couldn’t.

I wanted to get some voices from Midwood, Brooklyn, and the Pakistani community there, because the community was really decimated. It was awful what they went through. I was trying, but the folks who were working were so grassroots that it was pretty hard to even get in touch with them, let alone ask them to stop doing things to write something. I was listening to a podcast interview with Mohammad Razvi with the Council of Peoples Organization in Brooklyn recently. And they basically converted the organization into a food bank during the pandemic—they were distributing food for 300 people a day, like full bags of food. So the work has continued on Coney Island Avenue in Midwood.

I was struck by how many attorneys are in this issue, actually. That wasn’t by design. There were a couple of attorneys who I remember were working specifically on detention, specifically on special registration—I’m glad we got Elizabeth OuYang in here. The connection between Elizabeth and Theresa Thanjan’s pieces was actually great, but there are a lot of organizers, too.

And then there’s the work that was happening out of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA). When the NYTWA said to FEMA, “Hey look, we’ve been economically impacted because the Financial District is not operating and nobody’s flying right now, and that’s how we make most of our income,” FEMA’s response was, “Well, you have a mobile office so you can go get your fare somewhere else.” So there was direct service work going on to ensure people were doing okay, and there was also advocacy work to change the rules with FEMA. I felt like documenting as much of that as we could in whatever way we could would allow for other folks to access that and recognize people were getting involved in all these different ways.

I’ll talk really quickly about the Subhash Kateel interview in the AALR issue. I actually got to know Subhash over the years after 9/11. We had had these conversations looking back, but nothing this broad. Not only was he deeply involved in the organizing with Desis Rising Up and Moving and then Families for Freedom in New York, tirelessly working to support immigrant detainees and their families, but when he moved to Florida, he started a radio program called Let’s Talk About It! and through that platform he introduced me to a whole range of different things. As an organizer with a sharp political analysis, he welcomed people across the spectrum and working in very disparate areas to share their work, giving me a sense of the breadth of what “organizing” can look like, and the power of conversation across ideology and truths. He might not know it, but I actually owe him a lot.

I remember during our conversation feeling like, wow, this is something. And then Gerald, while he was transcribing, messaged me over a time, saying, “Oh my gosh, oh my gosh.” It was so affirming, because I felt like this is such a powerful document, and Subhash is really trying to remember. I think that cemented for me that there’s a power to the written word and that there’s also this opportunity with people who may not feel comfortable doing the writing themselves to find modalities and ways in which we can actually help them to document. There’s something super powerful about capturing people as they speak and then giving them the opportunity to look at it and edit. I’ve had these opportunities when people have said, “Yeah, I would love to get these people to write something together.” And I’m like, “Why don’t you actually do a roundtable and curate it? You can actually get these amazing voices and the energy of them together.” It’s not a new concept, but I’ve seen it particularly with people who don’t consider themselves writers who have so much beautiful knowledge and information and humor and grief—all those things to share.

I’ll say one more thing, which is about the DVD “Ten Years Later: Asian American Performers Reflect on 9/11,” which I’m really proud of. In my own journey, with whatever limited view I had at the time or even now, I felt it was hard to feel like mainstream Asian America understood how big this is. In Muslim communities, South Asian communities, Arab American communities, Sikh communities—this is their present, right? And then I saw Asian American spoken word artists who weren’t specifically from these communities speaking up right away. And you read Shailja Patel’s piece in the issue about separating “literary production in the U.S. post 9/11 into two simple categories: works of courage and works of cowardice,” and you’re reminded that not everybody was on point. But I really felt like Asian American spoken word artists were on the cutting edge in being outspoken. I don’t even remember how the DVD came up. I think the original call was for it to be a collaboration. Like Leah [Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha]’s piece, we recorded it at the APIA Spoken Word and Poetry Summit. We just went into a side room at The Loft in Minneapolis and recorded it. I am so grateful to Giles Li and Sham-e-Ali Nayeem for their curation and love for community.

JN

I was thinking a lot about Suheir Hammad recently and how she was the poet that I was reading and listening to the most right after 9/11.

You both have engaged in solidarity work since the publication of this issue. Can we hear more about the work that you’ve done since the publication of this issue, and the ways you’ve been thinking about solidarity?

RS

I’d say the two most important things that have developed out of all of this work in the last 10 years have been related to Palestine and South Africa. When I try to think about how I got there, it’s very hard for me to tease it out. I will say, in retrospect, I know that Palestine emerged as a kind of trace of a memory that suddenly burst into my consciousness. I had gone to a school in Bombay that was set up for a lot of expat U.S. folks, and the only reason I was going there was because my dad worked for what was then Esso, which is now Exxon. The connections are crazy, all these imperialistic connections. In the school, which was an amazing school, I inadvertently ended up having a very Zionist education.

Then maybe five years later, after my dad had died suddenly, I was living in Bangalore on a street with a lot of Iranian students who were fleeing the Shah’s regime, and I got a different kind of education. One day I went to the British Council Library and I saw photographs of Palestinian refugee camps, and I had absolutely no idea what they were—I literally went, “What is this?” I remember my Iranian friends saying to me, “What do you mean you don’t know what this is?” And I suddenly realized that certain kinds of histories are deliberately kept from you—that you were made to be deliberately ignorant of certain things.

It all was brought back into my consciousness as a result of hanging out with people like Rakhshi (Rakhshanda) and Sunaina, meeting my friend from Lebanon, meeting people in Boston who are Palestinian American, going to South Africa and realizing how Mandela and everybody else in South Africa see the liberation of South Africa as completely tied with the necessary liberation of Palestine. Looking at South African liberation leaders who visited Palestine and who came back and said, “What’s happening in Palestine is worse than anything we had in apartheid.” And then, taking myself to Palestine—I went twice. I wanted to understand at a small, basic, minuscule level what it’s like to live under occupation. I remember just thinking, I don’t even know how people do this.

With South Africa, it’s part of my teaching and my wanting to understand social movements around public health. I went there during the HIV/AIDS epidemic and saw how a young democracy handles that. And now seeing how a young democracy is handling COVID and how it’s handling things like water and sanitation and tuberculosis—that’s just completely tied up with my human rights work.

I feel very proud of what we did in the Asian American Studies space and our support for Palestine, but I don’t think we’re doing much at all in turning the discourse here in this country. BDS, our support for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, is a small portion of what we can do, but I continue to feel very discouraged at how the U.S. is not really engaged in Palestine.

More recently, because our campus is situated on the Boston Harbor in the Boston Harbor Islands, we’ve been involved in trying to center Native American and Indigenous perspectives in all the work we’re doing on our campus in terms of our research labs, our histories, and our curriculum. So I feel like that’s where my solidarity work is taking me: to learn and think about what it means to center perspectives that have been completely marginalized.

PRK

When I was younger I didn’t really understand my place in the history of this country. I had a history teacher in high school who tried to give us photocopied chapters from A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn, and I didn’t really read it. It was after I graduated from college, after I started to read Asian American literature and Asian American history on my own and with a few friends, that I went back and read A People’s History, and I was like, oh, okay, this is why he kept trying to give me this book. It gave me some understanding of what I’m told and then what’s behind what I’ve been told.

I think the experience of September 11 and the years after really made me realize that there are these huge movements of history that I actually have been a part of and that some people have no idea about. A few years ago, somebody who had been in New York the whole time, who’s in her seventies, a friend, a colleague, said, “Giuliani, he’s okay.” And I said, “But what about all these things that happened after September 11 with the profiling of Muslim communities?” And she had no idea. So I gave her the AALR issue, and she wrote to me after she read it and said, “I can’t believe I didn’t know any of this.”

I’m still on this journey, but for me solidarity has meant learning humility. Even if I know a thing, sharing a thing in a space where there can be shared learning and shared exchange is the place where that can actually make a difference. Through the solidarity economies work I do, I work in a lot of Black-led spaces. To be trusted in those spaces, as someone who will listen and also try to do what I can in support of movement work, is a great honor, and it also keeps me humble. To me, solidarity, though, is not “I got my access card and so I’m going to stay quiet,” or, “I got into the VIP room so I better not say anything or do anything to get kicked out of the VIP room.” It means that I have a responsibility, that I’m not an individual—I don’t care what America tells me. I have stories, I have communities that I’m connected to and that I care about.

In solidarity economies, we think about a grand unifying theory of how to connect justice frameworks with a way of decolonizing how we organize and relate to ourselves and to the planet in tangible ways. This means thinking about ownership differently, thinking about our labor and time, centering equity in all of that. And to really do that work means that even when folks talk about Black and brown self-determination on their block, we have to humanize the shopkeeper who’s on the corner. They’re not vultures, and they have stories too. That may not be the most popular thing to bring up, when it’s like, “Hey, there’s no fresh food in my neighborhood, and I’m not treated well in my own neighborhood.” Yes, absolutely, and those people who are running that shop most likely live upstairs from that shop, most likely have a landlord who is actually the predator, who may actually own some of the other buildings down the street.

To me, solidarity practice is not about shaming people about what they don’t know. It’s trying to be true to my own stories, and then listening. I have my own little support group of Asian American folks who care deeply about community, have done different things—cultural organizing, community organizing, service provision—who have struggled with the ongoing erasure of Asian Americans, even in racial justice spaces, even by other Asian Americans. We wonder: Why is it wrong for me to say Asian Americans have issues and face oppression too? Why is it not okay for me to say, “Our community has things that are going on, too?” That should be a moment for actually coming together. For it not to mean that your stuff doesn’t matter. For me, solidarity is to both make space in my heart for other folks’ stories, and then to find places where I can share stories too.

“Solidarity means that I have a responsibility, that I’m not an individual—I don’t care what America tells me. I have stories, I have communities that I’m connected to and that I care about.”

Parag Rajendra Khandhar

JN

I wanted to give you both a chance to share some last words while we’re here together.

RS

This is one of those moments when I don’t think there’s adequate language to capture the range of emotions and the possibilities. Parag, you talked about how sometimes people who do incredible work just don’t have time to write about it. Or they don’t see themselves as writers, and it becomes somebody else’s job to sit down and talk with them about it so they can just speak. And that’s one way of making sure that work gets documented and recorded and archived. Jyothi, I feel you have given us this opportunity to revisit something that when we did it, we perhaps recognized its importance, but didn’t think about its continued life. Or we didn’t think about whatever impact it might have had on people beyond that moment. It has been just extraordinary to think it has touched you after all these years, and now, through you, might touch other people again.

I also want to say, Parag, that it was a space in which members of our community came together, and that feels very special. One of the entries in the issue was about Desis Organizing [the conference] and how so many groups came together in May 2001, initially to figure out what they were all doing. They didn’t realize those connections they had made would become so crucial after the events of September 11 as people plunged into action. I feel like these non-crisis moments of making connections are really, really crucial, and reviving connections are really, really crucial, too, because you never know when you might meet again.

PRK

I was really proud of this issue. I am very proud of this issue. And I knew it would have a limited print run, and I didn’t know what would happen with it. I had wanted it to have a life online. To be able to revisit this is a gift. And to be able to share it so that people who want to access it can feels like such a gift.

Rajini, I really look up to you. Many of us do. I used to sell A Part, Yet Apart in the bookstore at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. The way you welcomed me in this role as a collaborator, as a co-conspirator, as a coeditor, I always felt like my ideas and perspectives were really respected, which gave me confidence because I was really in a place where I didn’t have a lot of confidence. I want to thank you. I really felt you were a mentor in this, you know? And also so gracious.

Your really being in this project in a real way is very different from how other people sometimes say, “I’ve got books, whatever.” No, you were absolutely in it, and I felt grateful for that. The esteem to which people hold you—you can just see from the people who are in this issue.

RS

Thank you, Parag. That is really deeply, deeply gratifying and affirming, and thank you for that gift of those words.

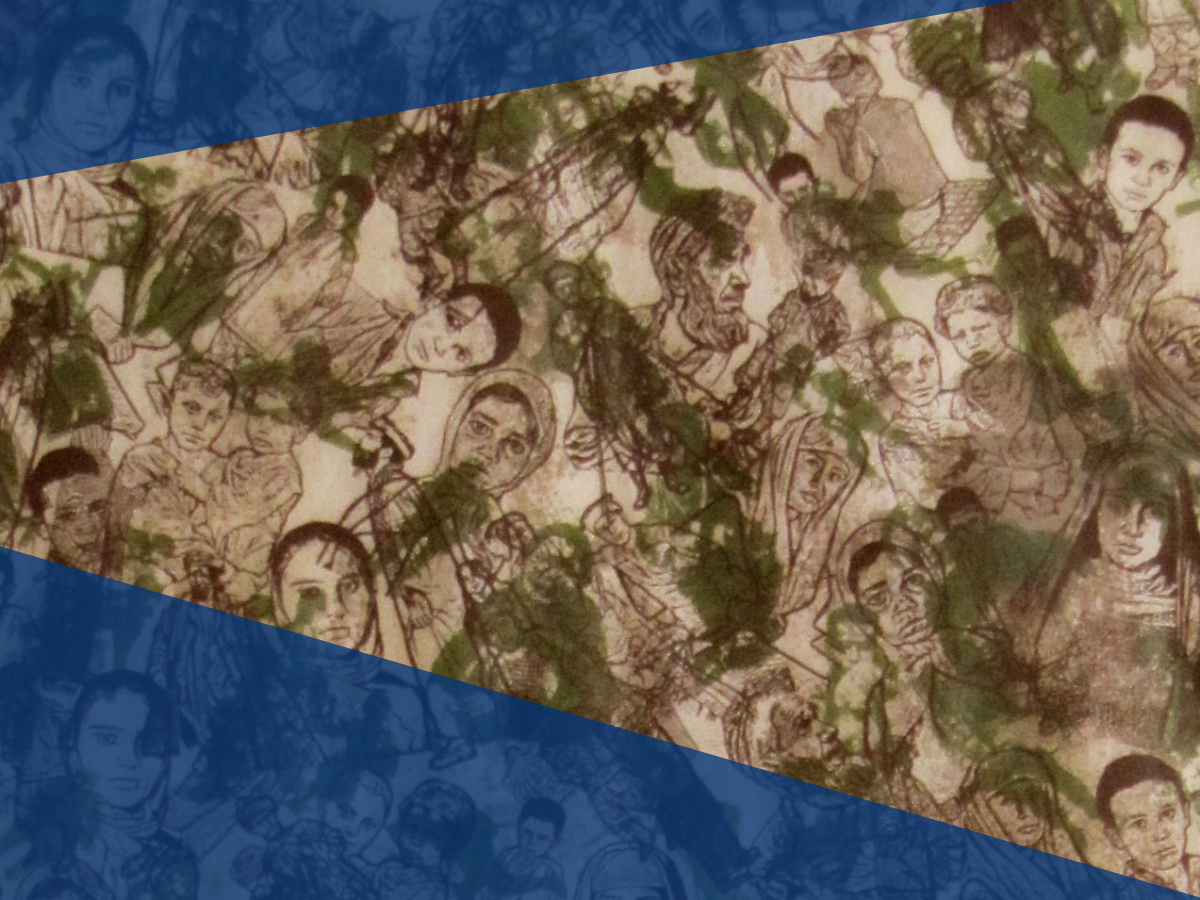

A note about the art: The image that appears atop of this conversation is a segment from the artist Tomie Arai’s “The Shape of Me,” a silkscreen monoprint created in response to a national call to artists issued by the American Friends Service Committee for the 2011 exhibition entitled “Windows and Mirrors: Reflections on the War in Afghanistan.” We are grateful to collaborate with Tomie for our notebook Living in Echo. Find more of Tomie Arai’s work here.