I was struck by the world I tasted—woods, Baja California granite, the winter of the grapes’ growth.

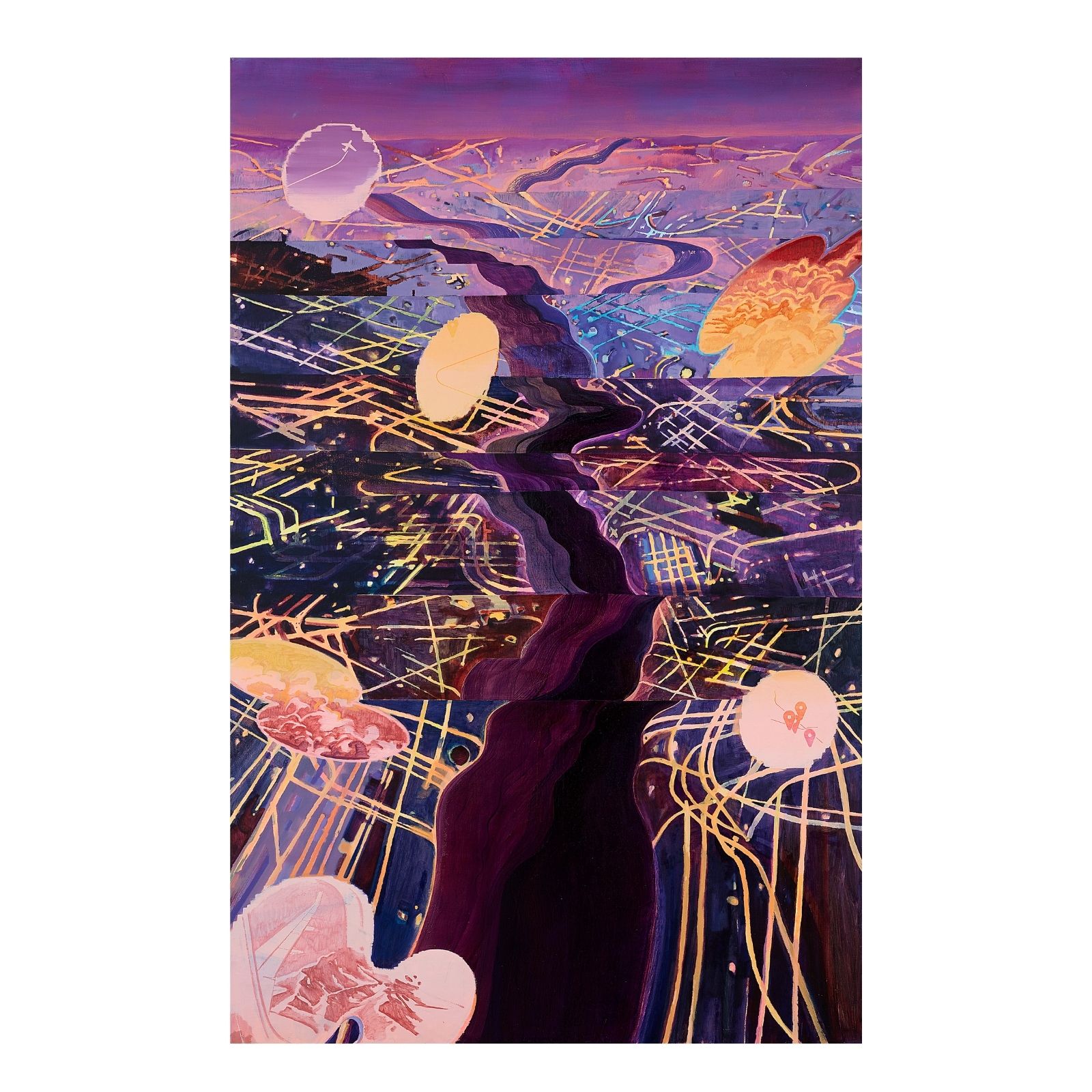

This piece is part of the Wine notebook, which features original art by Su Yu-Xin.

The first time I had the Mulatschak Blanc by Meinklang, I began a love affair with skin contact wine.

I’d never thought that wine could taste like that—that stone fruit could be funky, that wine could have that slight effervescence, that a single bottle could hold a kaleidoscope.

The first time I had tinto de verano was at a hole-in-the-wall tapas bar in Madrid, with a lunchtime Spanish tortilla. The wine was described to me as the “poor man’s sangria,” but I found its simplicity stunning: A Spanish grenache and lemon Fanta. I was hooked. On a hundred-degree July day, with a colorful straw out of the corner of my mouth, halfway deep in a glass of tinto de verano, I met the woman I’d almost marry.

We often went on dates to a coffee shop in Malasaña, where I would get a slice of tortilla and one, then two, glasses of tinto de verano. Somewhere on those dates, we slipped into each other’s lives like tap water through wrung hands. The napkins always stained deep red. Our skin pressed together.

My almost-wife never liked wine—as long as you like it, she’d say. She liked whiskey. I knew I didn’t like whiskey—but on a trip to Louisville, as she sampled the bourbon neat in the distilleries, I downed four different bourbon drinks. I kept waiting for the exception. The burn of bourbon stayed unchanging. We always had sex the same way.

In March of the next year, we were newly engaged and invincible. As I was gearing up to move cross-country into her apartment in Clarksville, Tennessee, everyone started leaving New York City to spend quarantine somewhere with backyards and open sky.

When I first arrived in Clarksville, the city started shutting down. I picked out two bottles of Monterey County chardonnay, and I drank them in four days. Deep in the uncertainty of the pandemic’s early days, we only left the house on Sundays—I needed to find a grocery store option that could last me a week at a time. I switched to boxed wine.

We spent lockdown doing all the domestic clichés, baking bread every Sunday morning and making spinach noodles from scratch on some Saturdays. My days had a constructed rhythm—every afternoon at five p.m., I would open the fridge, pull out the Bota Box of unoaked chardonnay from the bottom shelf, and pour myself a large glass.

It was the only ritual that was my own. In her apartment, with furniture she had owned for years and her concert mementoes on the walls, all that was mine was the suitcase filled with clothes on the floor, the makeup and shampoo in the bathroom, and the Bota Box on the bottom shelf.

In June, I took the courthouse wedding dress I had brought with me in March, and left Tennessee for Texas. My best friend offered me a room in her house in Belton—to heal, she said. Right at the edge of my heartbreak, in an empty house accompanied by Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, I attempted to recapture the taste of our first meeting by making a tortilla. The eggs from a hen-sitting stint for the neighbors—I’d never held so many eggs at once. In Texas, no matter how tightly I held something, my hands always felt empty. It was as if I was in water on the verge of drowning, trying to decide if my relationship was worth saving. I’d Googled couples counseling cross-country so many times, Instagram ads were popping up everywhere. I couldn’t hold them all.

When making a tortilla, the hardest part is flipping the partly formed omelette near the end. As I poured the egg and potato mixture into the skillet, the argument started to bubble from the speaker on my phone. By the time the tortilla was ready to be flipped, we were blown out in our anger, hurling insults at each other. When I loosened the tortilla into a serving dish, the insults and hurt had piled high. In the space between a Sunday and a Thursday, we fell apart.

In the space between the end of my engagement and the beginning of heartbreak, I read an article in Vice about the phenomenon where our sensory features quickly adapt to and make a habit of things we taste again and again. It’s why the first bite of a meal always tastes the best, the food neuroscientist wrote—it’s novel.

I tried to imagine drinking Mulatschak Blanc for the first time again.

After three and a half months of drinking Bota Box chardonnay, I didn’t remember any of its traits. My senses filled to the brim, my head swirling like inhaling after holding a long breath. In lockdown, I had finely blitzed nuts to make pesto. I had blitzed my own tongue—all traces of citrus, all floral notes disappeared. For months, it had been the same sugary note, dulling the instrument I had spent years sharpening.

When I moved back to New York City that summer to a kitchen without a dishwasher and only meant for Trader Joe’s meals, I put the tortilla aside. I only attempted it once again.

The November after, I made it for brunch with a friend.

While pouring the liquid eggs onto the potatoes, I heard cheers slowly rising outside my window. They only seemed to get louder and more raucous, and by the time I had taken the tortilla off the heat to flip it, my entire street had turned into a long block party for Joe Biden’s victory.

Because I made tortilla so rarely, in quick flashes through the years, it came to resemble lightning striking.

That Thanksgiving, I saw La Gorda Yori by Bichi in a natural wine store. I was newly single in New York City, and armed with a new, bright red fur coat; it was part of my quest to seek bolder, richer flavors. I was standing square on the hour of the year’s first snowstorm, and I was struck by the world I tasted—woods, Baja California granite, the winter of the grapes’ growth.

The cold had teased us for weeks. In the heat of the Tennessean summer, my almost-wife and I had been in the habit of falling asleep naked.

Bichi was founded by the Téllez family, who moved to Baja from neighboring Sonora. Bichi, which means “naked” in the Sonoran Yaqui dialect, marked the era in which I learned to walk around my apartment fully dressed.

That winter, I was granitic as the Tecate soil. Deep in pandemic lockdown, everyone on the Internet hung prisms in their windows. I saw myself in the little rainbows bursting from the prism, spilling all over the room. I’d never examined heartbreak so closely, from so many different angles.

I had seen myself as being open to any and all experiences, to loving anything if I tried it. Freshly in love with skin contact wines, I told a friend that “there’s not an orange wine I don’t like.” I tried the sour of a mattress on the floor in Tennessee. I failed at living in a place so completely not New York.

At dinner with friends that following spring, I was gifted a wine that, by all accounts, I should have liked. It was a chardonnay with skin contact, made from grapes that grew in intense sunlight and a long, dry summer. It was described in all the ways I liked—“buttery,” “funky,” “almost savory.” On my first sip, and then a second and third sip, a strange green apple–gasoline note turned me away. It rubbed abrasively against the sea urchin on my plate.

The last time I had sea urchin, at a restaurant in Calistoga, a wine enthusiast sitting next to me under the elm-covered stone archway whispered to me, “It’s the wine you don’t like that will teach you what you like,” and winked.

Yet, at dinner, face-first in a wine I did not like, it was as if I had lost balance.

In Clarksville, it was never about whether I liked stone fruits or citrus. My almost-wife touched me in the same ways, our skin tingling but never alight. We were waiting for one, or both, of us to change.

In New York, my handbag filling with the photo booth strips of a new life, I became interested in walking past—past job offers in other cities, past beautiful women. I could walk into a wine store and describe what I wanted. I could look into a woman’s eyes and know that she wasn’t what I was looking for.

At dinner with my friends, brushing up against the very exception I kept waiting for, I handed them the skin contact chardonnay: “I don’t think I like it, you should try it. I’ll look at something else.”

I instead took a chance on a wine that had sherry notes and deep amber. I knew nothing about it except that it was from La Mancha, Spain. My meal in front of me, a sudden, welcome surprise bubbled in my throat. I had landed on something new to love.

Late that night, it started to thunder. The rain down my window like wine fingers. In the dark, Esencia Rural “De Sol a Sol” Airén on the nightstand, I came in touch with my own skin again.