Tonight, too, there are turning lines…/ I say I do not know, do not know.

November 27, 2018

Plastic 10: Spotlight on Korean activist poet Song Kyung-dong and the feeling of an oceanic asking. Read the original Korean version of this poem below followed by a brief discussion.

The Sea’s Interrogation Room

I hear there are people who work at night,

waves breaking beneath their feet as if calming them.

I say I know nothing about it.

Tonight, too, there are turning lines, I hear,

waves from all sides opening mouths and biting.

I say I do not know, do not know.

Tonight, too, people are being dragged away, I hear,

waves rising abruptly, reaching their eyes,

so what about it?

I say that now I only want to forget it all.

Still all at a loss

as the waves strike my face,

I ask, What did I do wrong?

I just want to weep, rolling like gravel.

I pursue, saying I was a labor activist for 20 years.

On a shore I visited without any dreams

was the waves’ night-long interrogation.

Translated by Brother Anthony of Taizé, excerpted from Korean Literature Now, Vol. 41, Autumn 2018.

Brother Anthony of Taizé was born in England in 1942. He has been living in Korea since 1980, teaching English literature at Sogang University, where he is now an emeritus professor. He is also a chair-professor at Dankook University. He has translated works by many major Korean writers, mostly poetry, publishing some 45 volumes including poems by Lee Shi-young and Shin Kyong-nim. He is currently translating the poems of Park Nohae and Song Kyung-dong.

바다 취조실

밤에도 일하는 사람들이 있다고

달래듯 발밑에서 파도가 철썩인다

나는 모르는 일이라고 말한다

이 밤에도 도는 라인이 있다고

사방에서 파도가 입을 열고 따져 묻는다

나는 이제 모른다 모른다고 한다

이 밤에도 끌려가는 사람들이 있다고

벌떡 일어서 눈밑까지 다가오는 파도

그래서 어쩌란 말이냐고

나는 이제 모두 잊고만 싶다고 한다

아직도 정신을 못차렸다고

얼굴을 냅다 후려치는 파도

내가 무엇을 잘못했느냐고

자갈처럼 구르며 울고만 싶다

이십여년 노동운동 한다고 쫓아다니다

무슨 꿈도 없이 찾아간 바닷가

파도의 밤샘 취조

Song Kyung-dong came through AAWW’s New York space with Hwang Jungeun earlier this fall thanks to Korean Literature Now and we spoke briefly about his impressions and practice.

how is here: It’s strange一I’ve been discussing and protesting problems related to this nation and the US Army my whole life, and now I’m finally here一very strange.

what are your language(s): Through literature, I’m on a journey of digging up the languages inside me, to find which ones are in there. [Have you found any names for those languages?] … Perhaps they’re the languages of loneliness—societal loneliness, historical loneliness, existential loneliness.

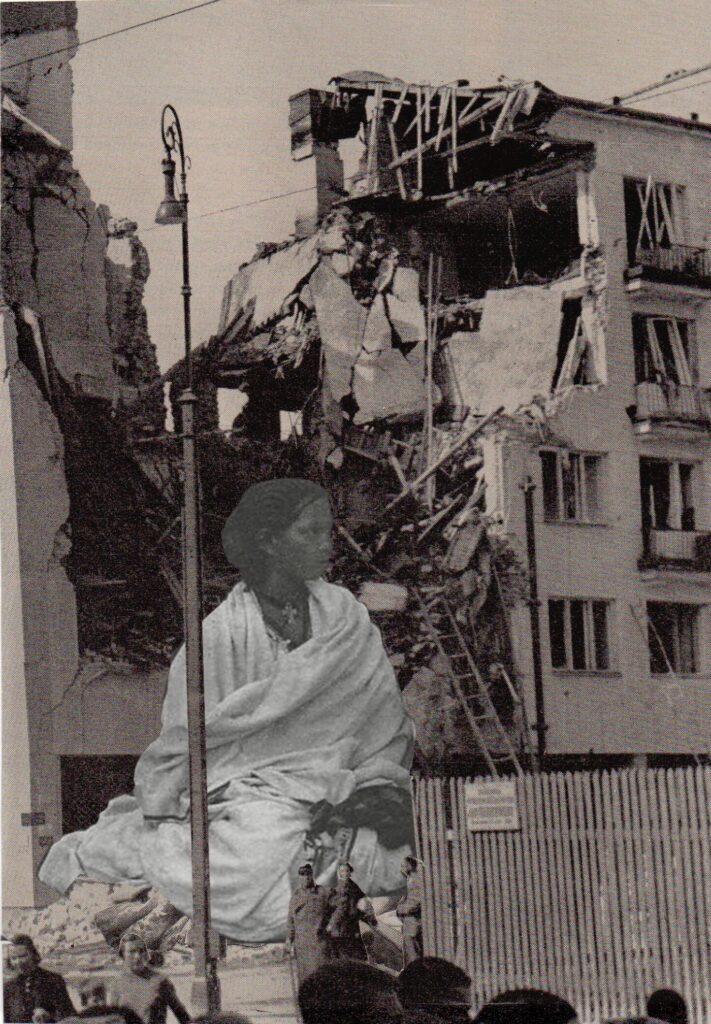

where do you write: I’m usually at protests. I rarely go home and I can’t really afford a space to write. I walk around the streets, particularly around where protests happen一that’s my library.

who do you read: Pablo Neruda is probably the most influential writer for me, as well as Kim Namju, [a leftist leader imprisoned in the 1970s and 80s for his political beliefs] who wrote and translated Neruda’s poetry from prison [as well as that of Ho Chi Minh]. What impresses me about these writers is how their revolutionary, activist spirit is also concerned with trivial things, and love.

what is “nation”: Nation is something to overcome. Nation is irrelevant to capitalist violence. The oppressed have to relate across borders to fight. Korean society is limited because of the division between north and south, but I believe we don’t have to be trapped inside borders. That’s why I threw away my nationality and named my book of poetry I’m not Korean [나는 한국인이 아니다, 2016].

a question from your translator: When you are writing your poems, to what extent are you primarily motivated by a wish to bring social and labor issues to public attention and to what extent is there something other, something more simply “poetic,” in your approach to writing? What for you does it most deeply mean to say “I am a poet”?