We are our skins; we are our hides. But my skin, and the skin of others like me, has been torn. It is at the site of this gash that our identity coheres, that our identity is espied.

I am a bilingual person. I am fluent in English and Tamil. My mother tongue is Tamil. I have a PhD in English. I am illiterate in Tamil. How did this dichotomy come to be? How does this shape a poetics? And what does one do with a pinch of sugar—that sweet stuff pillaged from colonies in the Caribbean, churned from the blood of India and Java, stolen for other tables? What does one do with a pinch of sugar? These questions belong in a triptych.

As Gloria Anzaldúa writes, “Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language.”1 We are our skins—derma, the Greek word, means “hide”—we are our hides. We are also what we hide. But my skin, and the skin of others like me, has been torn. It is at the site of this gash that our identity coheres, that our identity is espied. The way someone looks at a wound without a bandage. This is a story about that rip, that gash, and the activity of linguistic, ethnic, poetic identity at that site. I will suggest that this is a site of cleaving—a cleaving away from ethnolinguistic identities one is born into and the cleaving towards decolonial formations around the gash.

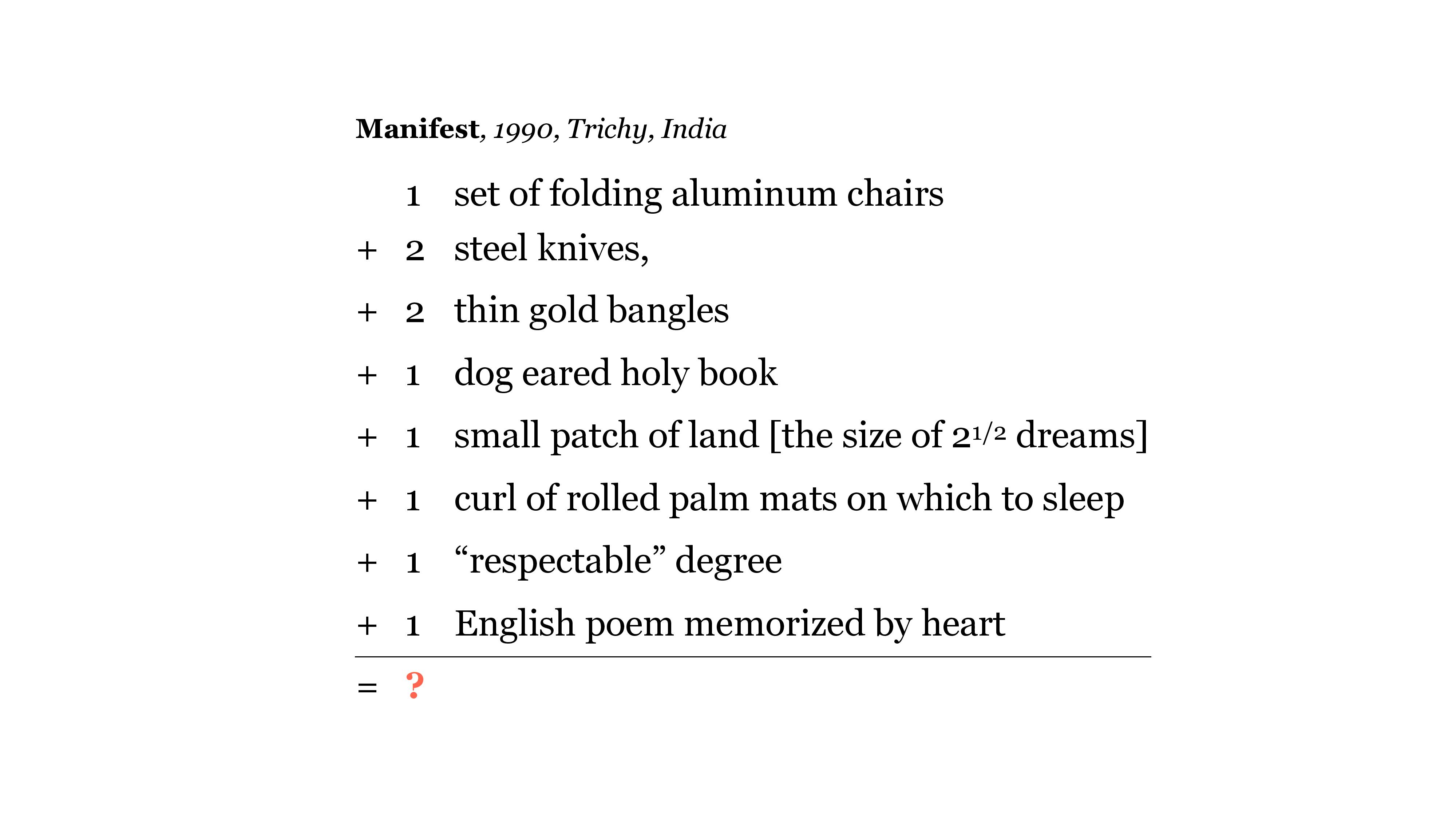

In 1990, I was seven years old and living in a place, in an idea, called “India.” In 1990, an idea called “India” is only about 40 years old. A 40 year old in 1990, where I am from, would own a set of folding aluminum chairs, two steel knives, a set of thin gold bangles, a dog eared holy book, a small patch of land the size of two and a half dreams, a curl of rolled palm mats on which to sleep, a “respectable” degree, and one English poem memorized by heart—to pull out when they met a white person and offer, like a damp daffodil held in a palm: Look, we are not savages. Look, we know of daffodils. And they are dancing in the breeze, too. This scene is a kind of primordium—a site for the formation of an organ that I didn’t even know I housed within me, until I wrote this talk. But it is a scene native to our shared linguistic condition: It shows up in Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy; it shows up in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake. It shows up as part of a manifest; it is embodied cargo in the diasporic drift; it varnishes our vowels, cuffs our consonants, grooms the tissues of the voice with a bit of spit and flick and fear of forgetting.

We committed poems to memory, anticipating occasions for recitations—poems waited like cats in humid alleys to startle unsuspecting guests at awkward moments: “Tell them a poem, no, darling, the one with the daffodils all over the place. And there’s so much breeze also. Tell them that one.” Poems were made for recitation. And good middle class Tamilian children were made to recite English poems.

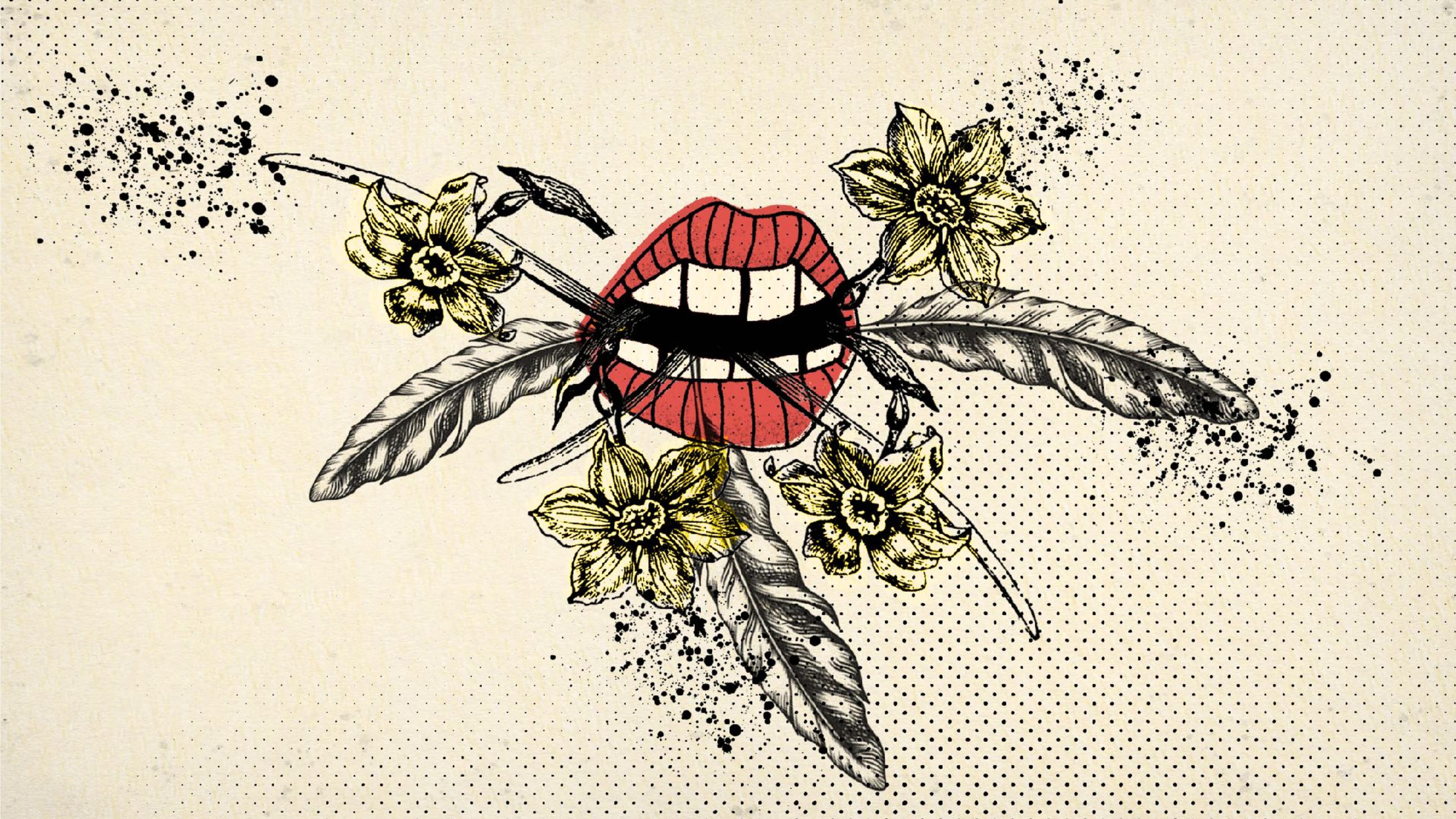

And so it was that this poet recited daffodils into bloom in a sweltering city in the Indian south. But. There are no daffodils in Trichy, Tamil Nadu—it is too dry, too warm. I did not learn about flowers through the delicate Kashmiri narcissus carved by Persian artisans into the snowy marble of a mausoleum, the Taj Mahal; not through the waxy frangipani and tamarind blossom of Rabindranath Tagore’s poems; not through firecracker flowers, கனகாம்பரம், tucked in my mother’s hair. I learned of flowers through the march of Wordsworth’s iambs. It is a terrible, distant botany.

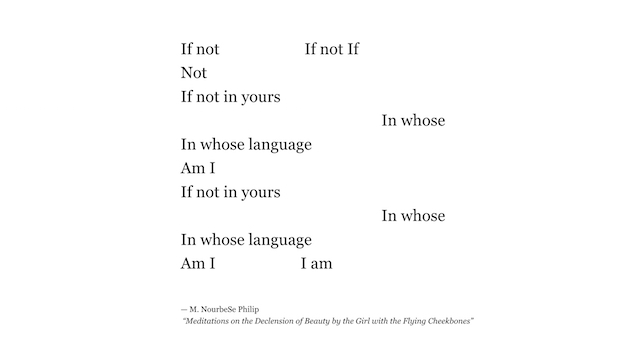

The Tamilian middle class had many children like me, who wore braids, had skinned knees, who mistook their English textbooks for their own faces, and who learned to memorize Wordsworth and Tennyson “by heart.” Or, as we say, where I am from, we byhearted them. We learned them nose in book, we learned them by heart, by mouth, by body, meter by meter, foot by foot, living hand to mouth, in the teeth of things. English was what we committed to memory; it, a language, was what our memories became. Or, as a British novelist informed me about Indian writers recently, after a reading I gave—you, your people have a way with words—ah, British writer, it is also that those words have had their way with us. The recitative scene is like a staircase that won’t go both ways. The words we learned never quite learned us. Yes, we are plurilingual—this is Caroline Bergvall’s word to describe a “writing that takes place across and between languages.” And yes, our language practices are often “exophonic”—this is Marjorie Perloff’s term for the practice of processing and absorbing the foreign.2 However, when we speak of borrowed tongues in reference to plurilingual writers and writers with post-colonial heritages, we must retain what is unabsorbed, unprocessed, ejected. We must ask too how this borrowing of languages is related to structures of borrowing and indebtedness generated by the one-way stairway that begins in the 15th century with Vasco da Gama’s rupture into Calicut and then continues, one bloody step after another, through to the World Bank.

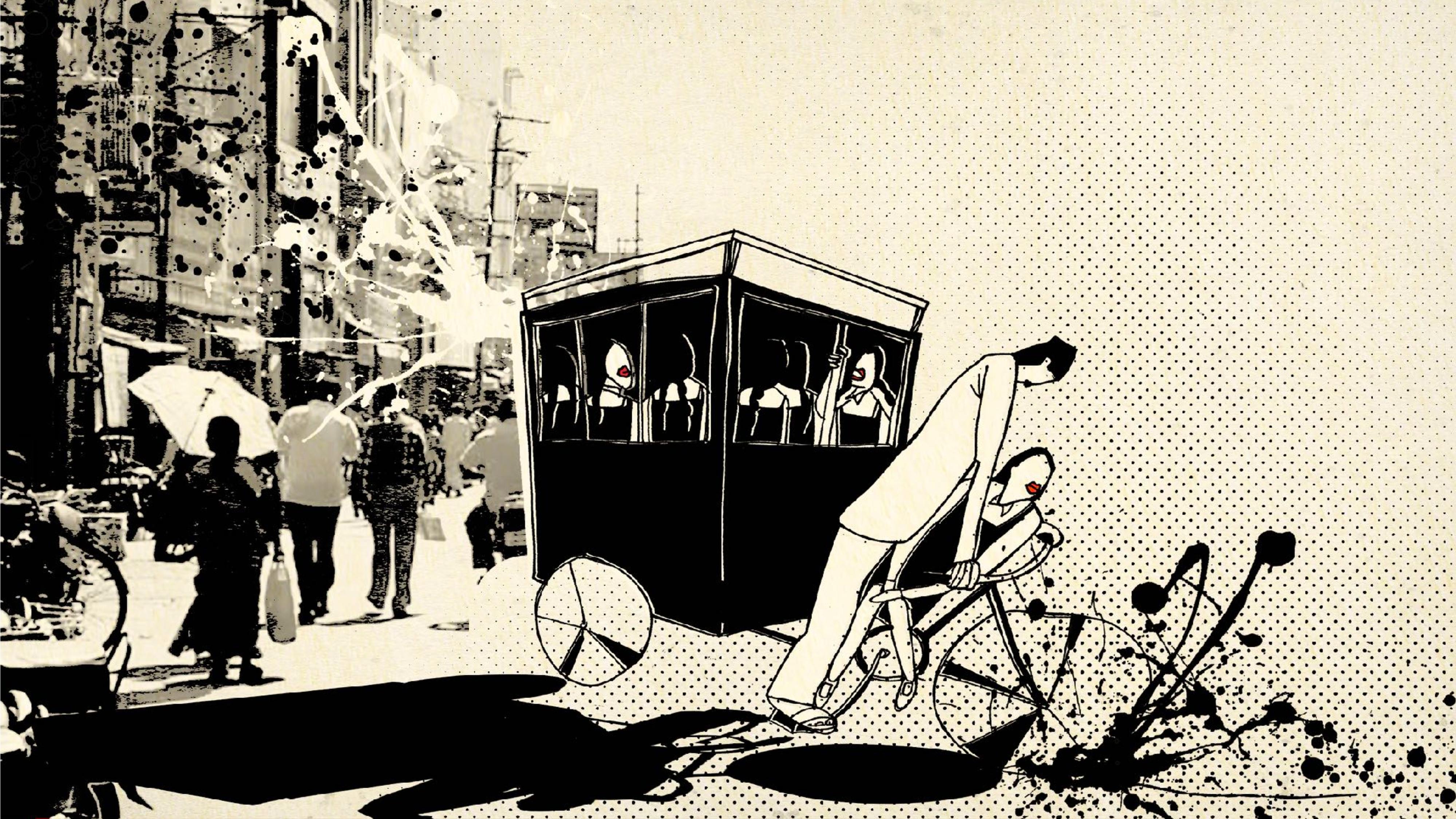

In 1990, I travelled to and from my school in a cycle rickshaw. A man of about 40 years motored this with his sinew and bone, pedaling over potholes on roads washed out by floods, eroded by decades of municipal failure brought on by decolonization. Decolonization is an undoing. Undoing affected our streets the way undoing a stitch affects the fabric—it leaves a cupped pit, a gap, a gasp in its wake. It is difficult to self-determine, to rescue a stitch in time, without leaving a hole or cutting the thread. We traveled these gaping streets to learn a language. At 8AM, a rickshaw man—a man of about 40, as old as the idea of India—carried four elementary school children, who were carrying Wordsworth’s daffodils in their mouths, to their schools, where they would shout the flowers out onto concrete floors and hot-tar playgrounds. Along for these rides came his four year old daughter, who he cared for while her mother cleaned houses. Along came her oiled pigtails, her blue skirt with the hanging hem.

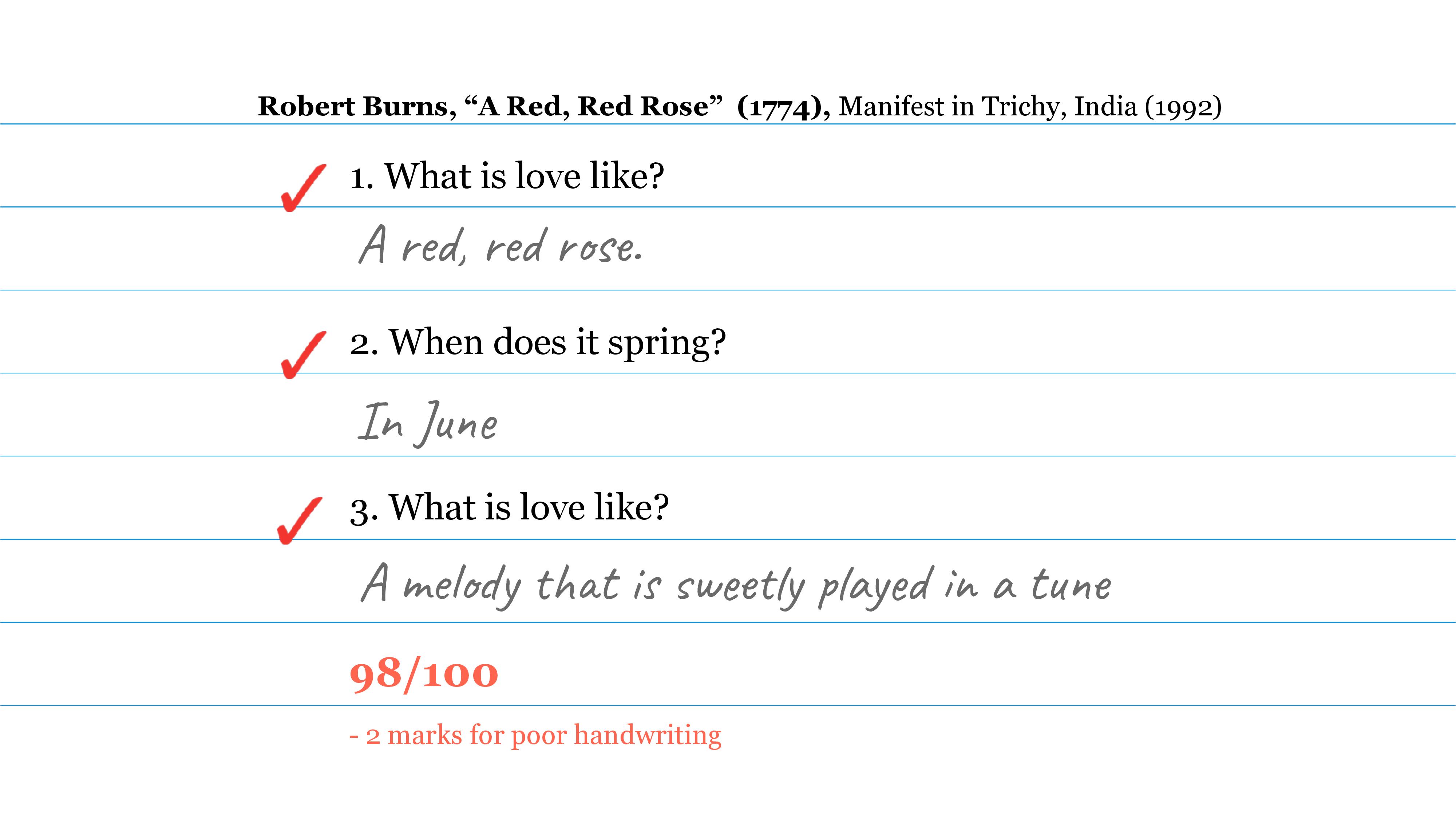

At 4 PM, he carried four elementary school children back to their cement and brick homes. These children carried Tennyson’s salty waves and Coleridge’s albatross, feathers sticking out of their gap-toothed mouths. He and We carried these poems, and with these poems, the memory of the colonies. And we spat them out on our stoops—what did you learn today, kannu?—borrowed weathers, strange feathers, gray rocks, red, red roses, and treacherous seas poured out onto our arid, sun-baked gardens, and drowned our sleepy snails—we had water, water, every where, [but] not any drop to drink. At every stop on his rickshaw route, the children would recite, in a sort of off-kilter, sand-dusted, crusty chorus, the poems we had learned—droning stanza after stanza, tripping over the syllables, busting our knees open on the rhymes:

O my Luve’s like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

We memorized poems, of course, for our exams:

These were the facts, according to Robert Burns. And eight year olds memorized poems as facts like their lives depended on it—because they did.

Tamilian mothers, who were educated in Tamil medium schools but who had decided to send their own children to be taught by Anglo-Indian English speakers, would greet their children as the rickshaw dropped them off. And at this site of recitation, on the edge of their homes, standing on bare feet, they would write down the poems in brown paper note-books, and they would mark the stresses and rhythms with their own shorthand, softly mouthing the words as we swung them out of the rickshaw carriage. These mothers’ tongues were the most silent wave swells, lolling to the shore, breaking with trepidation over the hard palate, foaming at the teeth. Their quiet copying was a way of coping with their eventual linguistic separation from their children; a way of acknowledging their children’s separation from their mother tongue. They ventriloquized their tiny ventriloquists returning home with empty lunch-boxes and mouths chock full of English, Scottish, and American poetry. But, we are no strangers to recitation—Tamil cinema’s defining features include dubbing and the use of playback singers; the recitation of memorized Sanskrit mantras during puja ceremonies are central to the practice and embodiment of Hinduism; the recitation of shloka, the metrical verse of epic poems like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana sing the chorus of small towns and metropolises alike. Whereas scenes of recitation at altars and temples in India work to carry forward heritage and Hindu doctrine, the recitation of English verse served a different kind of god.

Contemplating the colonizing effect of language, Frantz Fanon recalls a line from Paul Valéry’s “La Pythie” in which the poet describes language as “the god gone astray in the flesh.” The poem ends with this kinesthetic and synesthetic image: “Car une voix nouvelle et blanche/ Échappe de ce corps impur” (“For a new and white voice / Escape from this unclean body”): Valéry rants in awe of divine language possessing the subject and wrestling away a pure and white voice from a filthy, impure body. In Valéry’s poem, we observe the fetishization of pure expression; we observe the fantasy of exorcising from language its embodied and extra-semantic dimensions. However, in Fanon’s recalling of Valéry’s verse, god becomes the colonial power possessing and wrenching apart the colonized subject. Fanon compares the assimilating vocal apparatus to a possessed being, morbidly aware that systemic dispossession is the means to such possession. The language of the colonizer courses erratically through the body politic, inscribing its limits and refracting its affects, enunciating its difference even before it can speak. The speech of the assimilating, reciting subject who speaks so as to “exist for the other” is an open shell of a body taken over, nouvelle et blanche.3

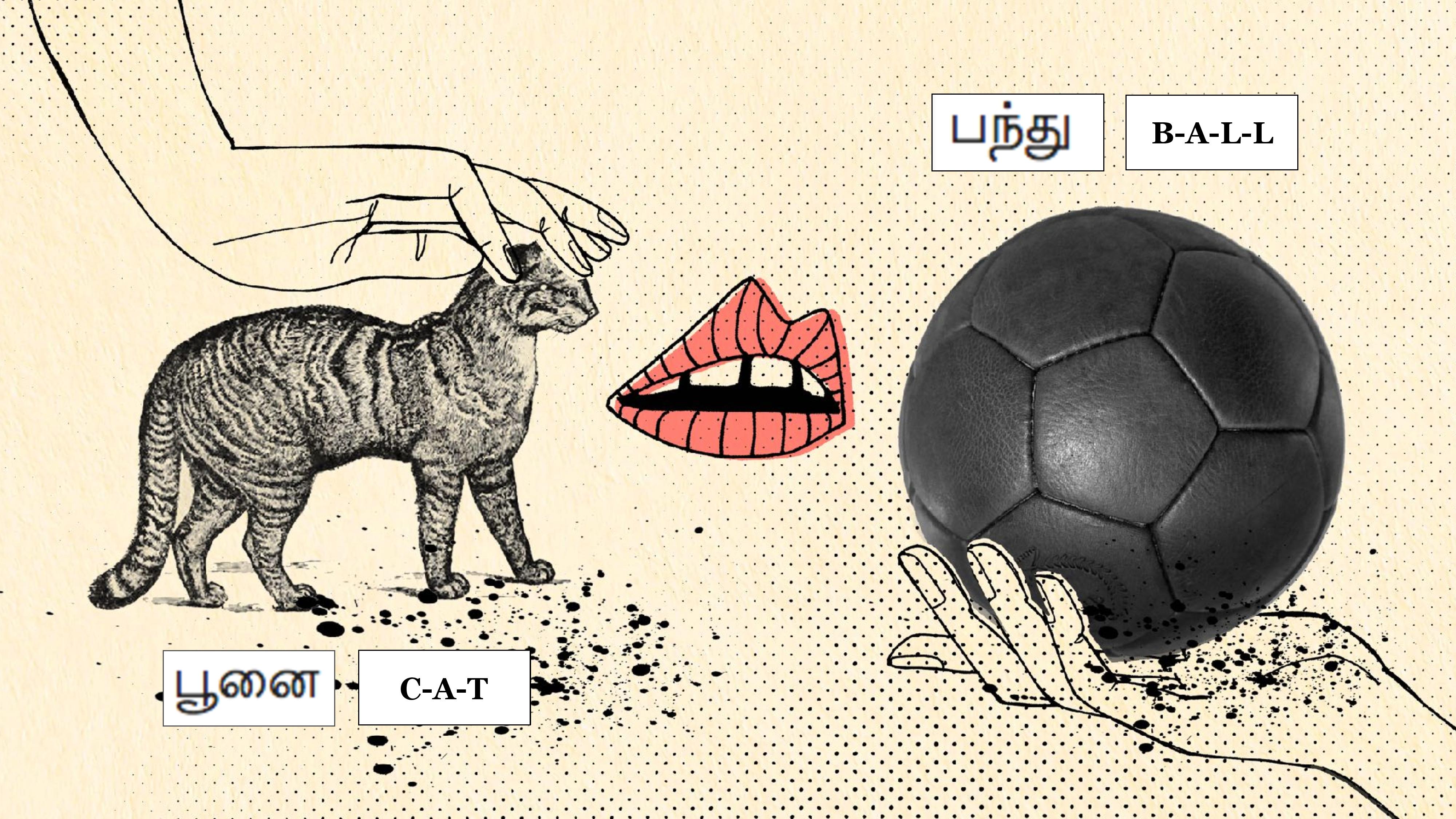

As I write this, the image of the silent mothers—those smiling mothers taking dictation from their baby Anglophones—rises like a ghost. But like all phantasms (phantazein ‘make visible,’ from phainein ‘to show.’), they make visible, they make known, they howl something into consciousness. It is their memory that makes me insist, at many turns in my criticism and poetry, on the fundamental and particularly postcolonial separation between poetic voice and identity. Because before my body took its place in the phenotypic parade (my appearance as South Asian), before my name took its place in the bureaucratic queue (citizenship documents, passports, visas), before I was called a darkie in grad-school, before I came to identify as an illiterate Tamilian, I first claimed an Anglophone “I.” That lean and inky bridge from self to self, from inchoate cry to speech, from subject to object (and back) is built at the recitative scene in a decolonizing India. This bridge leads to grander scenes, where I am committing to memory the English rhyme structures that organized my sense of a home: the C-A-T cat was on a M-A-T mat; the B-A-L-L ball bounced off the W-A-L-L wall. These arrangements would be pure phonic chaos in Tamil, where poonai (cat) sits on the paii (mat) and the pandhu (ball) bounces of the sevurru (wall). Claiming the Anglophone “I” was my unwitting act of unsettling myself in an unsettled land; an unwitting act of settling for and because of monoliteracy. It became a kind of home in my itinerancy.

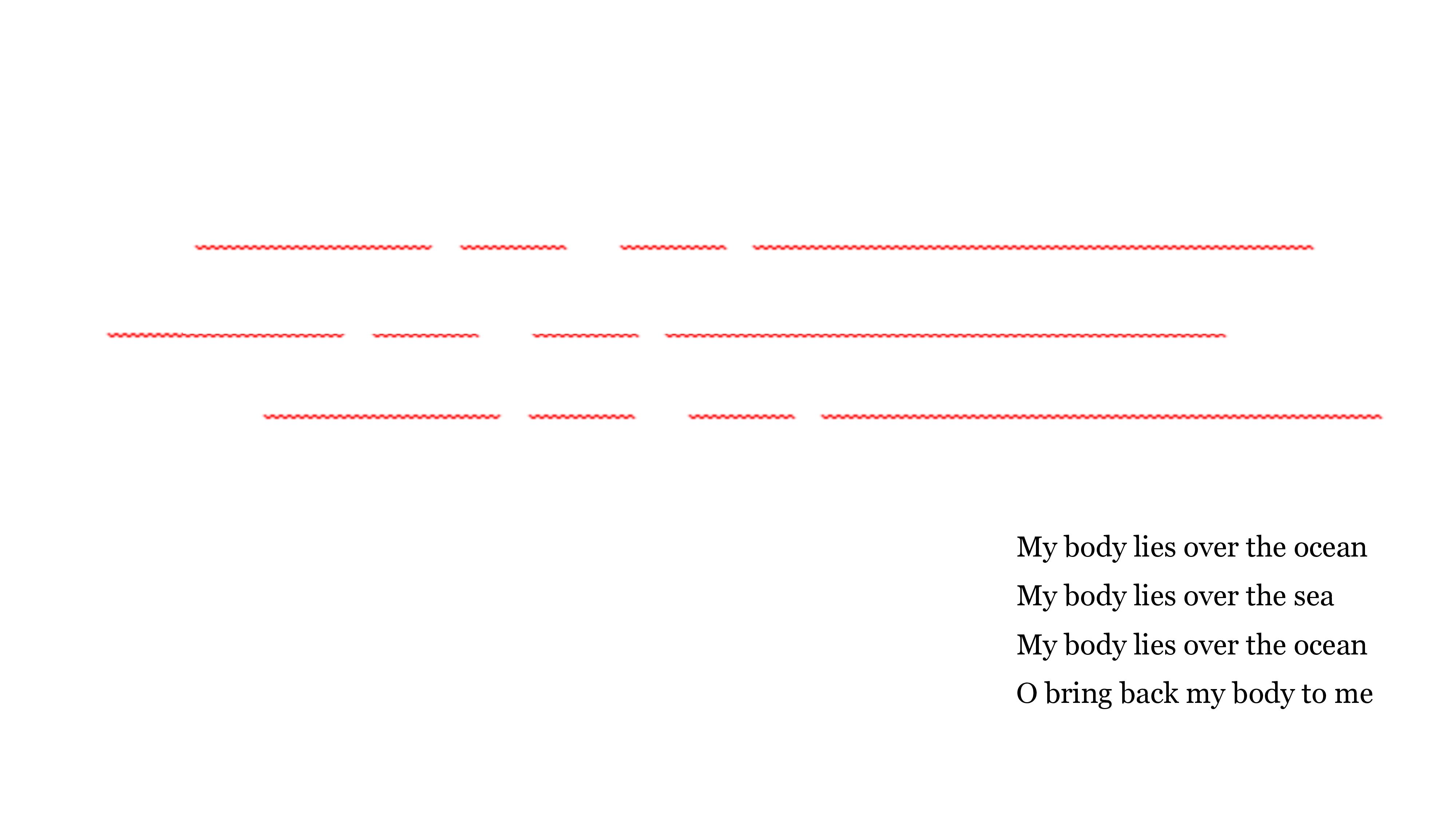

As I write this talk, Microsoft Word has underlined with red waves all the words that belong to my mother and all the words I will need to “add to my Dictionary.” Every time I do this, the red waves disappear. Every event at which I “add to Dictionary” on Microsoft Word is a moment where I am taking back what was taken from me and carried away on that one-way staircase. The “1835 Minute on Education (in India)” is one step on that one-way staircase. I lay daffodils on it as if it was a tomb. The “Minute” remains a racist historical ledger of reasons why English exists as an inextricable foreignness lodged in the bodies of poets like me. Thomas Babington Macaulay, its author and the definitive force behind Anglo-medium education in Colonial India, imagined “a class [of persons] who may be interpreters between [the British] and the millions whom [they] govern—a class of persons Indian in blood and color, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” Colonists were motivated by the hope that the literate core would serve as translating capillaries for a government who could not converse directly with those it governed. As a puppet of colonial discipline and control. Homi Bhabha has famously called members of this class of translators the “mimic man.” Our services as a translating class were initiated at sites of recitation, but we also know that in our history as “flawed colonial mim[ics], to be Anglicized, is emphatically not to be English” and in this way, mimicry departs from mimesis (radical or generic) and introduces the possibility of mockery—the mockery of models of history that would claim us, against our wills, as their own.4

The mouth of us mimics is rendered again and again in critical scenes of feminist imagining. It appears as an open maw, an open invitation to becoming through and despite invasion. In her book She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, M. NourbeSe Philip describes this as living with a “foreign lang/lang/languish, an anguish.” Philip offers images of the tongue as phallus, occupying the mouth of a subject who is both reluctant and invaded, but who is also wielding the organ to express that reluctance through trying, through test, and through the pleasures of getting it right. Or, as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha imagines this transformation of subject in the encounter with the object of language: “You read you mouth the transformed object across from you in its new state, other than what it had been.” Gloria Anzaldúa offers this maw in an image of the mangled, controlled mouth at the dentist’s office with a wild, untamable tongue flapping and swollen. Echoing her dentist, she asks: “How do you tame a wild tongue, train it to be quiet, how do you bridle and saddle it? How do you make it lie down?” Or, in Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ words, in Wells.

And a man

lifts up

a woman’s tongue

between his thumb and finger.

Or, in the words of Richard Rogers, who wrote The Sound of Music, “How do you solve a problem like Maria?” Or, in the words of Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady–“She should be taken out and hung/ For the cold blooded murder of the English tongue.” We all know too well the moment when, like Titus’ daughter Lavinia, we were bid to “now go tell, an if thy tongue can speak,/Who ’twas that cut thy tongue and ravish’d thee.// Write down thy mind, bewray thy meaning so,/ An[d] if thy stumps will let thee… play the scribe.” We play the scribes.

These recitative scenes are often read as sites of imbalanced power, where small bodies are offered up as abodes for the loft and heft of foreignness. However, as Janet Neigh avers, it would be too simple to recall these recitative sites as theatres of passive assimilation. Rather, she suggests, that one may experience these as “a point of entanglement” where we then “unravel” “the messiness of the colonial encounter.” One may observe how the decolonizing subject performs sliding between two prescribed roles—freak performers of a hegemonic alphabet or virtuosic masters of the same—to negotiate against the colonial “sanctions” (an interesting auto-antonym here) to one’s own becoming.5 Jamaica Kincaid imagines this scene articulated in the reality of decolonization: “[I write] in the only language [we] have in which to speak of this crime …the language of the criminal who committed the crime.6” Indeed, English is an institution in which I am doing the forensic work. I am mopping up the blood and guts to make a body whole—this is an impossible task. My body lies over an ocean. My body lies over a sea. My body lies over an ocean. Oh bring back my body to me.

Which returns me, like so many migrants, to the scene of the crime—to the scene of repetition and recitation. It returns me to the stoop on which a few mothers are waiting to try on the borrowed tongues of their tiny ventriloquists. It returns me flying towards them, back-pack straps flapping, steel lunch-boxes rattling, the red dust unsettled by my small feet. It returns me to the rickshaw ride back from school, where we recited memorized poems.

You see, in 1990, our little township in India had decided to welcome in American Television through cable. We were to become the new and tender audiences for the strange romances enjoyed by the wealthy and tanned upper-classes in The Bold and the Beautiful, the slippery and clumsy middle-classes in America’s Funniest Home videos. We were to become the new audiences for Operation Desert Storm—our/their invasions into Iraq. It was the first war that sent out live television broadcasts from the frontlines, through CNN. For us to become audiences of this war, to become new consumers of an American caste-system through cable TV, they had to find a way for a new god to course through the suburban landscape. They dug up our streets. They uprooted our trees. They pushed and ploughed over our pavement until the map of my childhood town looked like ruled paper on which to compose new, global images. When we were returning home, a rickshaw wheel caught in the rut of one of these cable furrows. The loosened roots of a huge banyan must have thrust out from the red earth. The wheel collapsed from the rickshaw, spun away. The thing of steel and canvas overturned with all of us school children and the four year old daughter of the rickshaw driver. This is about a gash in the earth—a geographical fissure that allows one country to erupt into another. This is about a poetics formed in a moment of catastrophe.

This is what I remember: The mothers on the block rushing from their stoops; the children being lifted like stunned plums from the pile; the rickshaw driver’s daughter at the bottom of that pile. Bruised and bloody, her mouth was a red, raw scream. The selvage of her voice, its edge, the subject falling off the cliff of that sound—here is an accident at the scene of recitation. This event is a gash—a cleaving apart, a cleaving to. This scene of recitation became, for me, a scene of catastrophe. A catastrophe turns something upside down so its mechanical underbelly is up in the air, wheels spinning, arms flung out of windows. Like any apocalypse, however minor, it offers an unveiling. (apokaluptein ‘uncover, reveal,’ from apo- ‘un-’ + kaluptein ‘to cover.’) An exposed etymological root, like the gnarled uprooted Banyan, sprung raw from the red earth. And like so many catastrophes, it became the scene that I repeated.

However, what I repeat, more often, is not the catastrophe, the over turning, but what happened right after. The accident had injured the driver’s daughter’s face. Her lower lip had been pierced by her own teeth. She must have bit down as we all fell on her, as we all became a crowd falling from the sky. Seeing this bloodied lip, my classmate’s mother ran to her kitchen and returned, her cotton sari swinging at her ankles, with a fist full of sugar. Sugar grown in plantations. Plantations from our land. Once owned by us. Though no longer. Like planting rice saplings in the drowned earth, she placed pinches of sugar crystals in the child’s bleeding mouth. Steady, and again, plant a pinch. Steady, and again, plant a pinch. I could see the sugar turn carmine, fall to the chin, skitter to the neck. Steady, and again plant a pinch, until the mouth was full of sugar and blood. The wound stopped bleeding, packed with sugar.

This crystal substance—the stuff for which the colonies were created, for which famines were justified, for which entire populations were enslaved. The sweet stuff of so much suffering. But, here is a mother pressing sugar into our wounds. Like her mother and her mother’s mother. And as surgeons now, in the United States, have learned to do. Sugar “draw[s] water into its gritty midst, through osmosis. This action [/] dries the bed of the wound.7” It facilitates the debridement of tissue; it kills and strips the parts of the body that are dead but hanging on. Debridement is the removal of dead tissue and foreign objects from the site of a wound. It is in this way, the scene of recitation becomes the scene of wounding, and subsequently, and importantly, the scene of rescue.

Poetic acts of debridement occur at sites of suppuration and puncture in documents that otherwise linger in our histories as woundings. It treats documents that function (otherwise) as records of subjugation, records of our bowing to the stripping of our sovereignty. In recent years, poets with postcolonial and otherwise marginalized heritages have entered these sites to press sugar to the wound, to draw dead tissue from the documents that describe untenable, fraught historical relationships between the owned and the owner in global trade, and have debrided their way through the fright of freight. These recitative scenes, however, turn towards the repetition of language from other master documents—insurance reports, legal briefs, autopsy reports, and court transcripts that function as a “a point of entanglement” (to recall Janet Neigh’s phrase) where we then “unravel” “the messiness of the colonial [or imperial or invasive] encounter.”

M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! debrides the documents recording an insurance dispute, Greyson vs. Gilbert (1783), concerning “recover[ing] [the] value of certain slaves thrown overboard for want of water.”

Hugo García Manríquez Anti-Humboldt debrides the North American Free Trade Agreement, which “has regulated and framed over $900 billion in imports and exports between Mexico, Canada, and the United States.”

Moez Surani’s ةيلمع Operación Opération Operation 行 动 Oперация debrides names of military operations conducted by member states of the United Nations from the UN’s inception in October 1945 to the incorporation of the Responsibility to Project (R2P) document in 2006.

Solmaz Sharif’s Look debrides the United States Department of Defense’ Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms.

Critics, especially critics who have maintained a more comfortable tenure within hegemony, have called debriding processes various things—the unbridling of language, of unleashing it from the source for it to arrive in the poem: citational, adaptive, quotational, conceptual, appropriative. Antonin Compagnon in Le Seconde Main ou le Travail de la Citation describes the doubling of language through “removal” and “graft” stating that: “one of the vigorous mechanisms of displacement, it is even stronger than surgery.” Marjorie Perloff’s genealogies in Unoriginal Genius are premised on Compagnon’s metaphor. Walter Benjamin describes a similar doubling (in “Karl Kraus”) that “wrenches” language “destructively from its context, but precisely calls it back to its origin.” Michael Davidson has usefully described this, perhaps too optimistically, as a mode through which the poet “participates directly in the writing of history by exposing the institutional venues through which history is written.”

But these words—origins, removal, graft, transplant, participation, surgery, displacement, wrenching—also have auratic connotations beyond their formal utility for those of us whose histories are evidence of such grafting, removal, transplanting, wrenching; for those of us unbelonged, those us displaced on land and in our tongues; for those of us who cannot be called back to an origin because that origin is, itself, wrenched or displaced further. So we debride, we return, shaking, to the scene of the crime, speaking in the language of the criminal who committed the crime—we find the wound and in it we pack sugar, we pack the sugar just as we juice the cane, we pack the sugar just as we cultivated the cane, just as we hacked it in the plantations, just as it left our soil in loafs and sacks, just as we left our soil in boats and in planes, and again we now plant a pinch of sugar, plant it like crystal seed, until the page is full of sugar and blood.

A version of this text was first presented as the Annual Rachel Blau DuPlessis Lecture in Poetics at Temple University.

1See Gloria Anzaldua’s essay “How to Tame a Wild Tongue in Borderlands/La Frontera”

2 See Perloff’s article “Language in migration: multilingualism and exophonic writing in the new poetics” in Textual Practice (2010). See Nathalie Camerlynck article “Caroline Bergvall’s Plurilingual Bodies” in Transnational Literature (2015).

3 See Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks

4 From “Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse,” in The Location of Culture, pp.85-92.

5 See Neigh’s Recalling Recitation in the Americas: Borderless Curriculum, Performance Poetry, and Reading (2017)

6 See Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place

7 See Elizabeth Rosenthal “Healing Treatment, 4,000 Years Old, Is Revived,” The New York Times (1990)