The writer and teacher speaks on navigating Mississippi’s racial politics and his experience in public education as “forged in violence.”

June 13, 2017

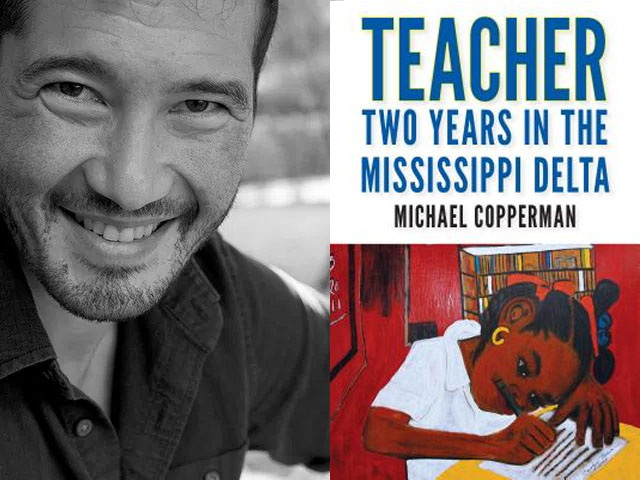

Several years ago, at the beginning of my PhD, I bumped into Mike Copperman outside of the English Department office at the University of Oregon. Having just moved to Eugene from Hawaii, I was thrilled to meet Mike—he was the first fellow Asian American I met at the predominately white university, and I instantly felt I should get to know him beyond the polite, superficial chatter that was so pervasive at the university. It became apparent to me, not long after we met, that Mike was not only a sensitive and skilled writer, but also a highly respected teacher with an enormous talent and patience for teaching students how to be better writers. Mike’s essays have been published in numerous places such as Creative Nonfiction, Salon, The Oxford American, and Copper Nickel, but it is the arrival of his memoir Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta that promises to earn him the attention and accolades he deserves. Although I have heard him read sections of the memoir at various public events over the years, when I read the book in print, I found it suddenly new, urgent, even bracing at times. Mike’s compassion for the young students about whom he writes and his frustration with the unfulfilled promises of public education form the core of the memoir. His elegant but restrained prose conjured the school children and Mississippi town in vivid detail; I continued to think and wonder about what had become of the students’ lives for days and weeks following my first reading.

Teacher blends artful prose, social relevance, and a narrative thread that crosses regional, racial, and class lines. Amidst a busy term of teaching, research, and job applications, I spoke with Mike about Teacher in person and by email to learn more about his process of writing the memoir, teaching under difficult conditions, and what he hopes readers and educators take away from the book.

Danielle Seid: Your memoir has numerous scenes of physical violence; for some reason, the scene with your father putting a teenage boy in a wrestling hold for acting disrespectful has really stuck with me. Above all, though, your descriptions of physical “punishment” at school, especially Winston’s use of the paddle with Antiquarian, continue to distress and unnerve me. I don’t want to sensationalize the violence in the memoir, but I am curious whether you think readers will be surprised by this violence. After all, the title of the book, Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta, has an unassuming quality for a memoir filled with such vivid descriptions of physical violence.

Mike Copperman: You know, it hadn’t occurred to me that “Teacher,” as a title or identity, would give readers the expectation that it would be

chicken soup for the educator’s soul. Maybe that’s because my experience as a teacher was forged in violence—it began in a segregated world created and perpetuated by violence through the history of slavery, Jim Crow, civil rights, lynching, mass incarceration, and persistent segregation… Violence was the razor wire fences of the white Academy football field to keep the black students out, and which seemed to me was also meant to hold kids in. Violence was the paddle that a big tall man swung [as] the means to maintain rules and order, the fists and feet and taunts and box cutters and iron knuckles and bruises hidden beneath uniforms that the children faced, bore, wielded. And yes, a part of the book concerns, especially in my first year, the violences that teaching there brought out in me as I entered that world and straddled its lines: not black and not white, not alright with the fences but working within them, not comfortable with the paddle but in need of order, not happy with mayhem but vulnerable in my hopes and frustrations, and so culpable for my own rage, my own capacity for wrong.

Will readers be surprised? Perhaps. I have tried to tell an honest story, which could never be that of a white savior who descends into rural or urban poverty to rescue minority children from poverty and despair, since I am not white and I saved no child from the life they were born into. A part of that honest story is to examine the school system I worked in, which in the years I was in Mississippi, relied heavily on corporal punishment. I was responsible for enough children being paddled to be forced to reckon with my role in that violence—if I sent a child to the office, they were likely to get licks. And yet the violence that I found I could not participate in was exactly what was encouraged by administrators, parents, and social workers; as a man in an elementary school, I was to establish masculine dominance.

I did not find it possible to be the Clint Eastwood of Promise-Upper Elementary, but I did find that I could be pushed beyond my limits, that I could grab a child by their lapel or collar, that I could yell and threaten, put a fist to a wall or desktop. And I find it impossible to interrogate the full meaning of teaching without reckoning with the shame of my worst moments, which I link to a memory from my own childhood: a teenage boy throwing rocks at my father as he ran on a track, and my father, a kind, gentle man, putting that teenage boy in a wristlock.

What I find compelling about the book is the way in which you describe your own struggle to fend off total resignation and exasperation with a deeply troubled segregated school system in rural Mississippi, as well as the Teach for America program. Your accounts of teaching first-generation and low-income college students at the University of Oregon, on the other hand, seem to reflect a renewed commitment to teaching. Do you think of your book as a cautionary tale for future public school teachers, especially those considering working for Teach for America?

It’s funny that you ask that—I recently got a tweet from a young woman who said, with the enthusiasm of several exclamation points, that she was sending the book to her sister, who was considering joining Teach For America, and I thought, uh-oh, she may not be sending along the bracing inspirational manifesto she thinks she is… However, I believe that we do need teachers and educators in our most under-resourced schools, and that organizations like Teach For America have a role in making our public education system better and more equitable. Let me put it this way: I know many, many former TFA teachers, as well as many public school teachers who have read the book and find it true to the immensely complex experience of teaching. Many say it resonates with their own experiences—perhaps the drama is higher, but what I write about is thoroughly relatable to any educator. I also know that most TFA corps members from back when I taught, as well as today, are simply better at teaching than I was. I think that anyone considering TFA or becoming a teacher should know what teaching badly can be like, because the time will come when they will teach poorly and fail—and, I hope, return the next day striving to teach better.

Those years in the Delta did change me—they made me understand the meaning of teaching well, and they committed me to the last decade’s work in diversity retention at a full-time college writing for under-privileged students. I would not have done that work if it were not for those years in Mississippi, and so would not have gotten to have the small but important impact I have been able to have, on students seeking a better future.

I guess what I am saying is that perhaps I don’t exactly understand what the book I have written means to others: What [do] they see or perceive? I have had many readers come up to me and tell me that they “don’t know how I did it,” or that “it’s amazing that I made it through something like that.” And I have to tell you, that even as those comments are immensely well meaning, I find myself biting back a sharp retort: “How ‘I’ made it through? What ‘I’ did? That’s not the point. The point is that those kids I taught stayed there, and went on with the circumstances of their lives. They didn’t get to leave, and go write a book.”

I have in mind a quote from Ian McEwan who has said that a novelist looks for but cannot achieve atonement in her writing because she sets the terms and limits in the novel, and there is no one outside the world she creates who can forgive her. Toward the end of your memoir, you reconnect with a student who achieved academic success in spite of the severe limitations of the Mississippi public school system. Was a part of you seeking self-forgiveness in the process of writing the memoir? Not just a reckoning with your two years as a teacher in the Teach for America program but also, perhaps, atonement for leaving the kids and the Promise community behind?

The novel’s limitations are different and the same as a memoir, I think. McEwan did, after all, write a book in which it is not atonement that his writer achieves, but rather, his own? our human? recognition of the burden of guilt, which enables us, the audience, to offer the forgiveness the protagonist deserves. If the purpose of memoir is reflection through retrospection—to consider the past from the vantage of the present, and understand what is true given the years and events that have followed—well, then maybe what memoir generally seeks is the recognition that while atonement is a lie, we can still recognize our own culpability; we can bear witness, and then we can try to forgive ourselves. But that forgiveness is necessarily partial until we ask for it in person.

I saw the young woman you speak of just last month, when I returned to Mississippi. The young woman, who I call Serenity Warner in the book, is so grown up now, so self-contained, smart, driven, accomplished, and so damn tough. Yet because of what she’s been through, she is also compassionate toward others.

I met with about five of my students who are now 22-year old adults, and quite honestly, I needed to sit down with the kids in a sunlit restaurant, or on the steps of a four-year institution they were about to graduate from, or on the front porch of the house they grew up in and still live in, to realize that I had been too hard on myself. I tried to do too much when I was 22, and I tried to carry too much in all the years following; I didn’t realize that what we do resonates beyond sight. Those kids, every last one of them, remembered their time in my classroom as special and different. Not necessarily “transformative”—not some sort of Dangerous Minds or Freedom Writers thing—but rather, accurately, and mostly positively. They were not often told in other classrooms that they could go to college and that they should; few of their teachers were so warm and energetic and foolish and loud and used so many big words.

When I told Serenity Warner I wished she would forgive me for what I’d done and what I couldn’t do, she laughed aloud. She went on to tell me every good thing about her year in my classroom, and a dozen things I had forgotten or not known that I had done. [Then] she put her hand to my arm and told me not to be stupid, that “We forgave you for everything when it happened, or in a minute or an hour, because you cared, and you tried your best. And it all made a difference.”

So, this last decade of teaching in Oregon was not atonement. I had to forgive myself most of all, it seems; I will always have guilt about leaving, but I have recognized that staying was not really an answer either.

One review of the book refers to you as an “Asian-American awoke to racial injustice.” Is this how you see yourself? What does it mean to you, as a non-Black person of color, to be awake to racial injustice in this moment of Black Lives Matter and increased visibility around police brutality and the prison industrial complex?

That reviewer has it right. About the rest, I wish I could say that I knew where to start—perhaps by saying that I take every video and incident and protest hard. I had hope that the Obama Administration’s move to limit for-profit prisons was the beginning of a real push to end the incarceration state, though I won’t be holding my breath now. Violence, injustice, and anti-Black racism are the reality of life in too many Black communities, and have been long before we had phones to record video, or hashtags to help us educate and organize. I am glad for the BLM movement and for Black activists having their voices amplified and heard. I think my memoir, in its focus on children in a poor Black community, should make it impossible for anyone to read about a Trayvon Martin or Tamir Rice and not know loss and pain and horror and outrage, because the Mississippi Delta is unto Florida, Baltimore like Charlotte, D.C. to Milwaukee, and unto Baton Rouge, Chicago, New Orleans, the Bronx, Philadelphia, Memphis, East LA, North Portland, rural Carolina, Seattle, St. Louis—

I guess what I think, too, is that we know how far we have to go when we see white nationalism resurgent with Mr. Trump.

Almost everyday, I hear or read about the countless problems plaguing public education in the US, from implicit racial bias in the classroom to grossly underfunded school programs. Your book is incredibly timely and should be read by everyone, whether an educator or not, who is concerned about the state of public education in this country. As a teacher, what pedagogical possibilities do you see for the book?

Since this book is about being a multiracial Japanese-Hawaiian Russo-Polish Secular Jew in a place ruled by a black-white binary and segregation, and about what it means to teach in an under-resourced school, it offers a lot of pedagogical possibilities—Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta is being taught in a Race and Racism class this fall, being assigned as a text in a Creative Nonfiction workshop, and has been chosen as part of a Civil Rights event. I am traveling to these institutions and classes to directly meet with students and discuss a mix of issues, narrative, and craft.

Moreover, chapters in the book have just been anthologized in Creative Nonfiction’s new Norton book, What I Didn’t Know: True Stories of Becoming a Teacher, which will be used in many teacher’s colleges and education programs. And lastly, a couple chapters are being used as a text in all the composition classrooms in one of Mississippi’s largest state colleges. My hope is that anyone reading the book who wishes to teach it (either for its perspective on race and class, its direct perspective on educational inequality, or for its narrative craft) will do so—and I will gladly Skype in to any classroom or talk to any writer or academic about teaching the book.

I’m sure you have many more stories about teaching you could share. Will you continue to write about teaching? Or can we expect something totally different from you next? Perhaps a dystopian sci-fi novel? As I’m sure you know, all the cool kids are reading and teaching dystopian sci-fi right now.

Hmmm. I may one day write something with fantasy or sci-fi elements, which are my first love. I am always writing essays, as the work comes, and I am almost done with a novel that is nothing if not ambitious. So, we will see!