I needed the concoctions F poured to quiet the things that grated and grew wilder each year—the confusion of being part white in an Arab country, part Arab in an expat world.

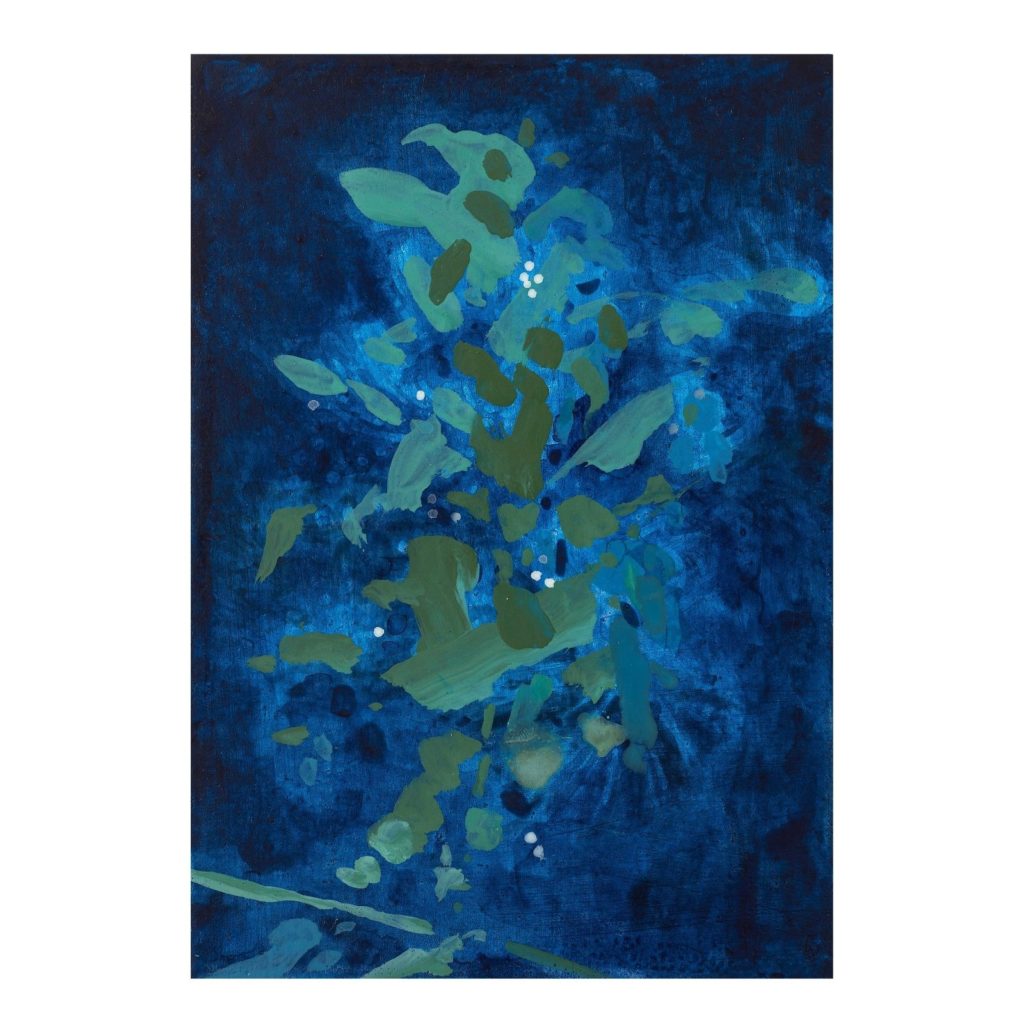

This piece is part of the Wine notebook, which features original art by Su Yu-Xin.

1.

It was the weekend—probably a Thursday night, the last day of the Saudi work week. I was surrounded by a dozen or so expats all holding glasses, their laughter swarming the air at a pitch that almost frightened me. I would have been around thirteen. It was this moment when their raucousness would begin to make sense, when I’d realize there was a reason the men and women I knew as teachers and parents seemed to come unhinged in this house.

The villa was the home of my friend F, the daughter of an American contractor and a German woman who tutored princesses. Her parents were glamorous and gregarious, frequent party hosts who treated children like their peers. Their style was antithetical to that of my Christian mother and Muslim father, who, though religiously at odds, were matched in their conservatism. Along with sex and love, drinking was absent from our family lexicon and my sheltered imagination. And this was Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in the early 2000s. Alcohol, like women drivers, gay sex, and public criticism of the King, were illegal and subject to severe punishment.

And so these things happened in furtive, coded ways. Later, I’d learn about embassy parties and taste smuggled, brand-name whiskey. Occasionally, there was a jug of bathtub-brewed beer, which was gulped with good-natured groans. There were the clear bottles brought by expats who blinked out of absent, red-rimmed eyes. This watery liquid was a harsh grain alcohol they nicknamed sid—short for sidiqi, the Arabic word for my friend. This they mixed with juice or the cans of wildly marked-up Schweppes they occasionally scored. But by far, at most soirees the alcohol of choice was muddy, homemade wine.

The wine was served in one of the mismatched mugs or tumblers that spilled out of the too-full cabinets, cluttering the counters alongside used-up cheese boards and crusts of pita bread. It would have been poured out of one of the repurposed green glass bottles that had recently held grape juice—perhaps Al Rabie brand or Danya. (Later, I’d wonder if there was something tongue-in-cheek about the choice by Saudi manufacturers to sell their halal beverages in containers that could be mistaken for Bordeaux.)

F’s compound, in those pre-Iraq War days, was a breezy microcosm of American exceptionalism. The short, straight streets had been built by a military contractor, then selectively populated by English teachers and ex-Marines. We walked to her pool in our short shorts—the kind I never let my father see—and bought Dove ice cream at the adjacent store. Instinctively, I was coming to know this as Westernness: every day like a vacation, safety in separateness. Even before al-Qaeda began targeting such spots, the gate to this community was guarded by a checkpoint and a tank. Men in buttoned shirts and belted guns searched cars for bombs but looked the other way when a woman’s purse clinked with liters of “grape juice.”

My compound, in contrast, was small and quiet, mostly populated by Arabs and East Asians who, though technically expatriates, were excluded from the term and the corresponding cliques. “Expat,” in that world, implied white—mainly those hailing from the United States and the UK. Select European nations were included too, with an odd Australian thrown in. (There was also the Black woman serving as the U.S. Consul General, who attended only daytime activities and smiled through references to Condoleezza Rice.) There were exceptions—the Peruvian couple whose son played on my brother’s baseball team, the Indian siblings who played on mine, the half-Japanese, half-Georgian girl on whom I had a heavy crush. But these special cases came with credentials—advanced degrees from Western institutions, high-power positions at American companies, an Anglo-Saxon spouse.

It was a precious, protected bubble in which these expats moved. With their private drivers, Filipino maids, gated communities, and hazard pay, theirs was a heady, pseudo-colonial life. True to imperialist tradition, they saw themselves not as an insulated elite but as outposts of civilization amid a barbarous majority. They bonded through mutual exasperation over the locals’ inscrutability. They griped about the perpetual lateness of the Arab, all his backwards hilarity. Of course, there were also the daily trials of the desert heat, gridlocked traffic, and the lack of name-brand mayonnaise.

So of course, by Thursday, they all needed their sadiq, the tumblers of wine, the collective sympathy. As F’s best friend, I was usually there, at the periphery, an Arab American child soaked in their let-off steam:

Saudis just don’t understand deadlines!My driver was forty minutes late!

Their kids, you know. They have no discipline.

The store was closed for prayer—all afternoon!

I think my maid is stealing from me.

F was pouring herself a glass when she made the offer to me. Would you like some wine? I hesitated, stumbling into the thought—oh, is that what everyone is drinking? As my mind whirred, adjusting to this revelation, F’s mother chimed in from behind. To F—give her a little bit. To me—just give it a try. As if coaxing a shy child to play with other kids, she was firm but encouraging. I stiffened for a moment, torn between the thought of my own mother and F’s mom, who I always desired to impress. I accepted the drink. The pair watched me take my first sip—sour, inky, sweet—before F added I like to cut mine with Diet Pepsi.

She picked up an open, silver can to demonstrate, giving a good pour to herself, and then to me. We both sipped. Now, the grape jelly bean flavor opened up to notes of carmely aspartame, abrading my tongue with chemical fizz. Drinkable enough for me to drain the glass, enjoying the gummy bubbles as they stained my teeth. A few minutes later, I was surprised by the heaviness pooling in my limbs, the way my purple-kissed lips seemed to double in size. Around me, the lamplight and laughing voices grew thick and close, a palm curved to fit my shape. I felt taller, and like music, tuned.

The next morning, I returned to my usual state—shuffling, hunched, tugging my shirt in all directions. I had recently begun avoiding mirrors, bewildered at my thickening thighs and the inexplicable hair appearing there. So uncertain of all things but my shame. No explanations came from my mother—not for my period, these changes, or the way boys would soon start exploring me. My body had become a part of her silences. But when I arrived at F’s home the next Thursday afternoon, I had barely shed my abaya before suggesting—how about we have some wine? It mortified me, to speak my desire so brazenly, but I yearned to pass through that trapdoor again. I longed to drain that syrupy drink, to find my clumsy, confusing body transformed into something wondrous, full of delicious heat.

And so, for years, I was one of the noisy, illicit revelers, tongue brushed dark, laughing more the less I felt. Sometimes, one of the tipsy adults would touch me, or ask me to sit on their lap. It was always the Americans—always, they said it was in good fun. F’s father, occasionally, would chuckle—careful. Not her. Her dad is an Arab, you know. Religious too. A real Baba. I laughed as if on cue. F’s mother told me later to enjoy the attention, while I was still cute. Of course he shouldn’t have, she told me after spotting one get handsy. He has a wife back home, kids. But these men have to let loose, you know. Under so much pressure in this country.

Later, I needed the concoctions F poured to quiet the things that grated and grew wilder each year—the confusion of being part white in an Arab country, part Arab in an expat world. I began pouring my own by the time George W. Bush’s war made places like F’s compound, bodies like my blonde mother’s and mine, targets for terrorists. Eventually, the expat parties would cease. Most of the club had been evacuated. Others were no longer in the mood. The production of homemade wine, however, would only accelerate. A few still gathered to drink quietly, the American Forces Network flickering, muted, on TV. The last time I saw F’s mother, she was bandaged, bruised, and emaciated. She’d stopped eating, only drank. She kept falling down the stairs.

2.

My father had his first glass of wine with his TOEFL class at a bar in Chicago. He was twenty-three, a Palestinian refugee, freshly arrived on his first flight west of Cairo. Ready to make himself something, or anything. They went out as a group, led by the teacher, part of an American Culture module. He swallowed his guilt with the first swig, advised himself that now was the time to have an open mind. He would never remember the vintage or the taste, only the warm, fuzzy mantle that lingered as he picked his way home on icy streets. خمر, the Arabic word thought to come from حمرة, red. A cousin of محمر, a word English doesn’t know. Still, Google makes a straight-faced attempt to paraphrase: محمر as blushful. A color clasping a body, growing from the inside out. Open, reddening relief. The sense he found inside that cup—of okayness, of تمام .

He’d need all that to help him cross the room a few months later, at a party with his classmates where he spotted my blonde mother. It was a moment of reversal—in that room full of ESL students, it was she who stood out, appearing un-belonged. Yet hers was a difference that stoked desire—she looked just like Princess Diana he’d recall decades after that night. Beautiful, but something told him she would not be like the other girls. The ones whose flinching made him محمر, but not the happy kind. I thought she might give me a chance. Down his throat went the خمر, and in him bloomed the red. Lionel Richie on the stereo, outside a mirage of snow. When he and his blushful cheeks approached, she smiled and pinked back.

3.

At my wedding, my father will not touch the wine—not even as he gives a toast. He hoists a water glass instead, brandished to remind me he’s halal. He needs his borders now, searches for power in a no. I understand that thirst. Today, he is watching his daughter, his firstborn, Filasteeniya girl, marry a Yahood. An unforeseen twist, uncharted waters for us all. In all the years of his diaspora, I have never heard him speak one word of hate. But he has never had a Jewish man this close to the threshold of his home. Not since the Israeli soldiers corralled him, behind his mother, onto a truck. That was Gaza, five decades ago this month.

During the year of my engagement, I drank a bit too much. After the champagne we popped, after my boyfriend popped that ring, I needed the false تمام found in a second glass of wine. When we called my father to tell him the news, I heard what I had feared. Why does it have to be him? I thought this would be a phase. Are there no Muslims good enough? Hand in hand, my new fiancé and I hung up.

The voicemails accumulated. I only listened to them when drunk. I love you, binti. Ya baba. I’m asking you. As a father. Please, find someone else. Later, I will tell him I have built a different equation for my life, my own, careful ratio of duty and love. I ask him to come meet me in my فرح , to شارك in my joy. Every night for months I will shiver a little bit, saying my own hybrid prayers for a world with space for both these men. When I can’t sleep, I pour a little more. حمرة as replacement, surrogacy, a bridge.

4.

Two years inside of a pandemic, three years from the wedding toasts, my father makes a trip. In the apartment I share with my husband, I am watching them embrace. Too many months we have been distanced, every day brushing against death, watching the world buck and heave. It feels like it’s been winter for years, but on that cloudy November morning our kitchen is all kinds of red and warm. Hot honeyed عجين and translated jokes. My father reaching for the third time to pat my husband on his back. Son. Thanks for having us. He replies أهلا و سهلا. I feel each word, a kindling.

Tonight we will introduce my father to Szechuan food. My husband suggests dishes, but my father has one request. How about some saké? He points to the menu, to this unknown drink. Is it a kind of wine? When it comes, he will lead us in a toast. He’ll outdrink me by far, his brown eyes growing sparks. Later, in bed, I’ll cradle a peppered belly and cherish the burn.