Five essays in a new collection from A World Without Cages show us the creative work of movement building.

December 18, 2020

A World Without Cages imagines the end of mass incarceration and migrant detention by bringing together the work of writers on the inside and on the outside. This project aims to nurture writers, activists, and intellectuals to dream new worlds beyond punishment, policing, surveillance, segregation, and exclusion.

The first three collections, published in 2018-2019, included work emerging out of AAWW’s Witness Program, a fellowship for writers of color to witness and write about mass incarceration through site visits; meetings with those directly affected by incarceration and detention; and ongoing correspondence.

“What if abolition is something that sprouts out of the wet places in our eyes, the broken places in our skin, the waiting places in our palms…what if abolition is something that grows?”

—Alexis Pauline Gumbs

In reflecting on how social movements generate new questions and possibilities, Robin D.G. Kelley says that movements can do “what great poetry always does: transport us to another place, compel us to relive horrors and, more importantly, enable us to imagine a new society.”

This fourth collection brings together writing by abolitionist organizers on the creative work of building a world without cages. These writers show us how practices of care can be radical acts of disruption that help us build, nurture, and tend to alternative worlds.

To house and to feed our communities—to provide care and reclaim the space to do so—is at the center of our political actions. Providing care can be seen as dangerous and threatening.

For example, a tent in a public park, a visible shelter to sleep and to rest, is deemed illegal. “Where could we go to be safe?” asks Victoria X after police raided their community encampment—grabbing people and seizing people’s precious photographs and documents, supplies, and water.

Assembling this collection was a collective effort, crafted through relationships over texts, phone calls, letters, and conversations. These five essays demonstrate the imaginative vision and practice of abolitionist organizing—the persistent ingenuity that comes with demanding more and demanding better.

Safear writes of longing for home—one that they have never yet seen but exists in a dream space between now and later. A home that could be. They reflect on a strange past, one in which pieces of paper dictated whether people might live or die or whether they could eat.

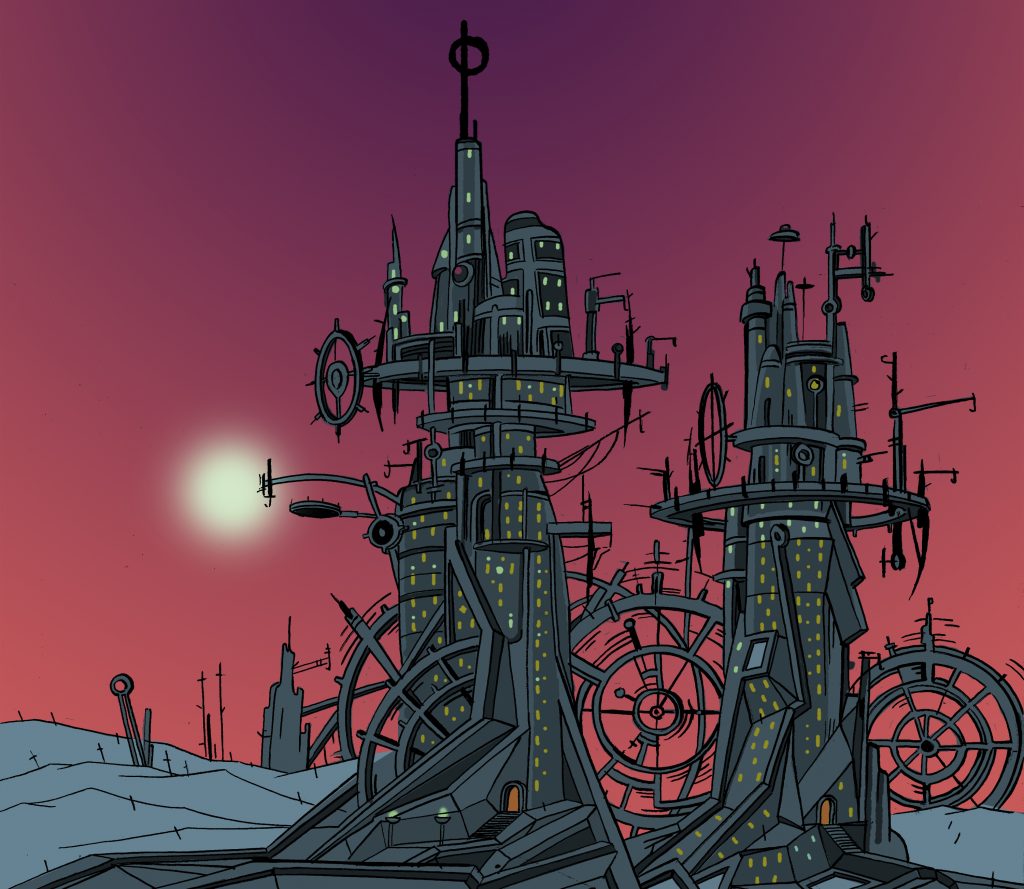

Original artwork by Chanthon Bun shows this visceral longing and the taking flight of this imagination.

Victoria X describes the care work necessary to hold together community and the urgency of housing justice in the fight for abolition. She shares reflections from organizing at Abolition Park, an encampment in New York City’s City Hall and a public space that became a home to many unhoused people. There was a library and a garden. There were daily teach-ins. At 3:40 a.m. on July 22, 2020, police raided the encampment, violently displacing people from their home. Since then, Abolition Park continues collectively working to provide safe housing, meals, and medical care in their network.

In a two-part series on feminist South Asian diasporic organizing for abolition, Mon M. and Sharmin Hossain discuss the internal community work necessary to be in solidarity with Black and Dalit liberation struggles. They talk about the necessity of international analysis in connecting incarceration to imperialism; creating community-based responses to violence without the state; and refusing “gilded cages” or false solutions.

Olivia Ahn’s visual essay includes memory field sketches and graphic propositions on prison doula care. They ask us to consider how to provide care in spaces specifically designed to separate and dehumanize people. “Many prison doulas are forbidden to provide physical touch to most clients who are incarcerated,” they write. Instead stacked paperback books and Tupperware containers become used for pain management techniques.

Together, these writers speculate and dream about worlds of abundance and show us that these worlds are already here.

—Rachel Kuo