From the crop fields in the 1900s to modern-day hospitals, the history of Filipinos in the U.S. is a story of survival and resistance.

May 29, 2020

Every night at 7 p.m., I hear my neighbors readying their noisemakers, from pots and pans to repurposed World Cup vuvuzelas, for the new quarantine tradition in Yorkville, just blocks away from New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Lenox Hill Hospital—the “Clap Because We Care” salute to essential workers.

When I join them in clapping, I silently think about Tita Rose, a cleaning crew member at a nursing home upstate, who is recovering from contracting Covid-19 ; Tita Noemi, a nurse at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital, who has decided to quarantine herself from her husband and two autistic children rather than risk bringing the virus home; and another nurse friend Kym who, with her co-worker, started a singing tour at New York-Presbyterian Queens to keep their co-workers’ and their patients’ morale up.

I think about how the majority of those deployed on the front lines—agricultural laborers, grocery and food delivery workers, nurses, and healthcare professionals—are people of color and immigrants, many of whom are now being called viruses and told to return from where they came.

And I remember that this is nothing new. Filipinos have been fighting America’s wars for over a century, from the Pacific theater of World War II, to its wars in Korea and Vietnam, to AIDS in the 1980s (my mother among the recruits for the front lines then), to Covid-19 in the present. We are welcomed and valued in this country for our economic utility and are expendable when there no longer is a need for us.

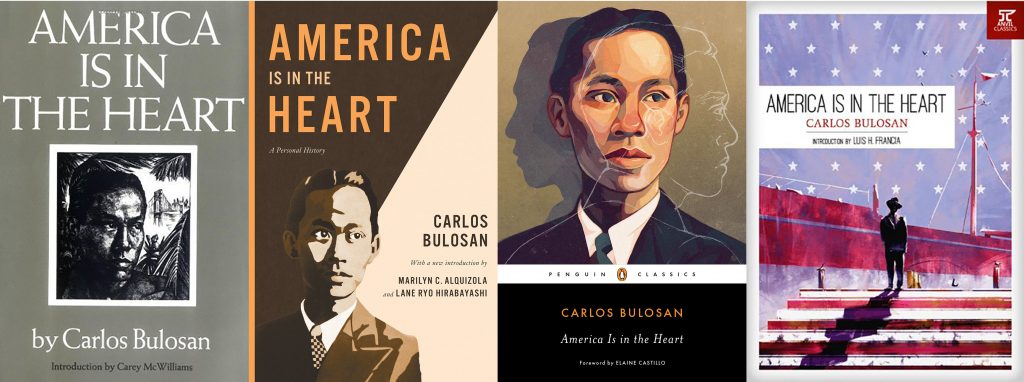

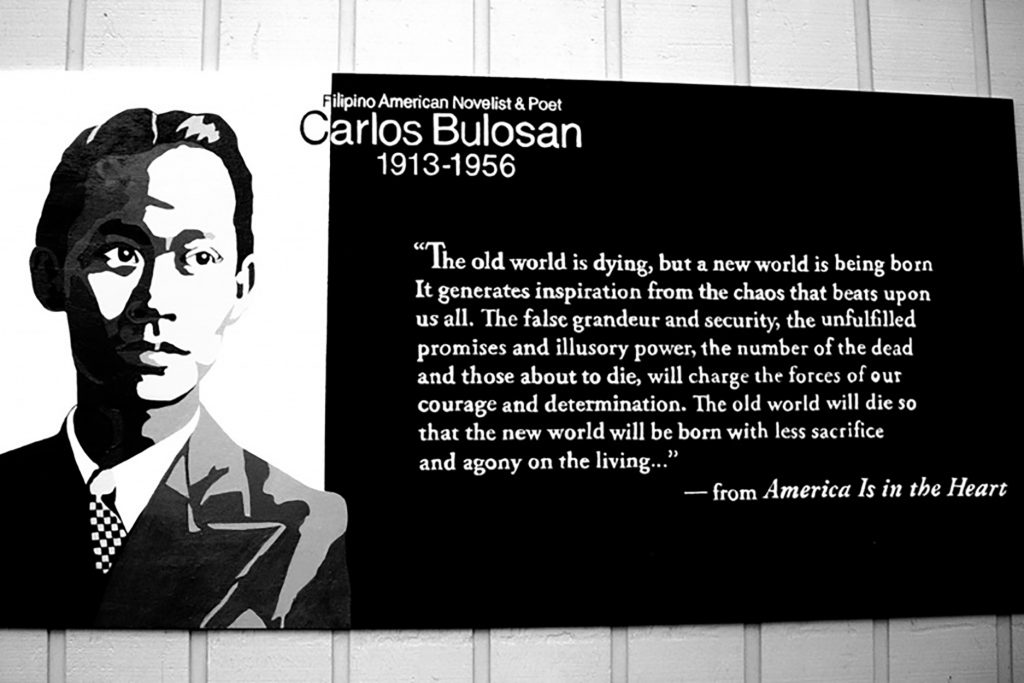

As an immigrant to New York in my teens, I found the semiautobiographical novel America Is in the Heart by writer and labor organizer, Carlos Bulosan, to be the first that profoundly resonated about the experience of being Filipino in the U.S. Bulosan hailed from Binalonan, Pangasinan, an agrarian village in the northern Philippines two hours away from Baguio City, where I grew up.

Like Bulosan, my grandparents on both sides escaped the difficulties of farming life in the provinces (specifically, Narvacan and Nagsabaran, Ilocos Sur; Sual, Pangasinan; and Balaoan, La Union) through a college education. They set their sights on the nearest city, Baguio, which once served as the summer capital of the American colonial government from 1901–1913 (Camp John Hay, the American military base in the city, remained active until 1991).

Perhaps my grandparents’ motivations weren’t that different from what Bulosan articulated when he left Binalonan for Baguio (then America in 1930):

“I looked back through the [bus] window and saw my father and [older brother] Luciano becoming smaller and smaller in the distance. Then it came to me that my life there was too small to float the vessel of my desires … I knew that even if I went back to them, after many years of loneliness in another land, I would not be able to pick up where I had left off. I was going out into the world to build a new life with untried materials …”

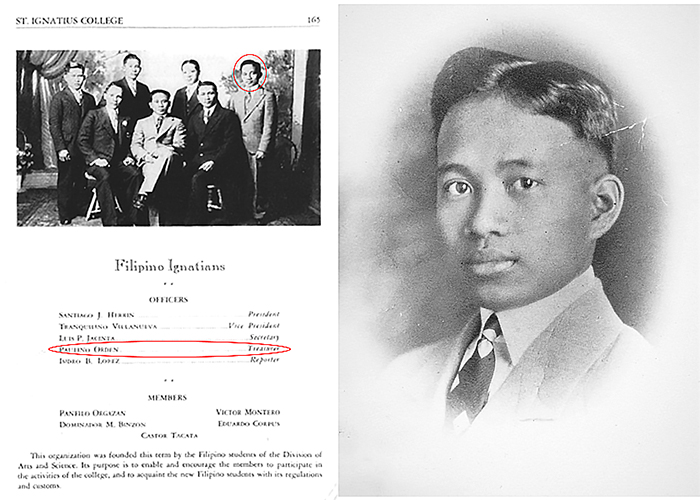

My paternal grandfather, Lolo Pilong, was the first in my family to migrate to the U.S., around the same time Bulosan did. What I know of his brief time in this country is pieced together from my father’s scant memories and my own cursory research. In the late 1920s, when the Philippines still was considered American territory and Filipinos U.S. nationals (although not full citizens), Lolo was granted the opportunity to attend St. Ignatius College (now the University of San Francisco).

The family’s only photograph documenting his experience in California was cropped from a page in his 1929 yearbook, featuring the officers of the Filipino Ignatians (of which he served as treasurer). The group’s purpose was “to enable and encourage the members to participate in the activities of the college, and to acquaint the new Filipino students with its regulations and customs.” In the photo, Lolo stands erect in a double-breasted suit with his hair carefully parted and combed back, gazing assuredly at the camera.

What isn’t captured in the image is the desperation of a young man who had to pick citrus fruits and cut sugarcane in hundred-degree heat on farms in Stockton, Merced, Visalia, and across the San Joaquin Valley in order to survive (rent and living expenses weren’t included in his scholarship, after all). He found that the only jobs available to him and other “little brown brothers” (a pejorative for Filipinos coined by William Howard Taft, the first American Governor-General of the Philippines, and a term in common use by white Americans throughout the early 20th century) paid a dollar or less a day in canneries and on farms, where workers followed the harvest north, from California, to Oregon, to Washington State.

Dad recalled that Lolo ripened mangoes by wrapping them in newspapers, the way he learned to wrap himself for warmth, nightly in the fields where he labored.

What isn’t apparent in Lolo’s face is his disillusionment that, contrary to what was taught in school, not all men were equal in a country plastered with signs that read “No Dogs and No Filipinos Allowed.” He had arrived in the U.S. at the onset of the Great Depression, a period of scarcity that heightened racial discrimination and violence by white working-class nativists and that pitted one group of migrant laborers against the other.

I can only imagine what California was like at that time from Bulosan’s manifold accounts of the discrimination and violence that Filipino migrant workers, the manongs, faced. A particularly unforgettable incident occurred one evening after a labor organizing meeting, when Bulosan and his two friends were abducted by five white men. They were driven across a beet field into the woods, where they were beaten. One of the men was stripped naked, tied to a tree, and tarred and feathered.

Lolo returned to the Philippines in 1938 with nothing but a suit and a few bottles of shampoo, so the story goes. He spoke little of his ordeals in the US, but the one thing he impressed upon his sons was to remain where they were and not chase after the American Dream. According to my father, Lolo tried to explain the difference between white and brown men this way:

“The Northern White Man lived in a cold climate where he saw long empty spaces during winter. There was then a constitutional coldness in him that predisposed him to be a predator-in-waiting. He saw the world as harsh, and therefore something to fight and conquer. In that dreary climate, he could not experience anything sweet.

On the other hand, the Little Brown [Man] who came from the warmer climates of the South experienced warmth and bright days of blue skies, green fields, now turning golden, now turning brown; sunsets of dazzling pink, oranges, purple and deep red, and a variety of sweet fruits. His spirit was more relaxed, more at peace with his surroundings, more gentle, less calculating and wary of the stranger. He was thus likely to become a prey of the Northern White Man.”

Lolo also returned a heavy drinker and gambler. There is a vivid scene in America Is in the Heart where Bulosan comes across the Manila Dance Hall for the first time. Here were Filipino pickers, cannery workers, and domestic servants, almost unrecognizable in tailored suits and hair slicked back with pomade.

In one night, they spent a whole season’s earnings on blonde American dance hostesses and at the bar on bottomless glasses of whisky (Johnny Walker White Label was Lolo’s particular poison). Of course, what these men—untethered from their families and stranded in the U.S., since most couldn’t afford either the passage home or the humiliation of return—sought but failed to buy was an escape from their lonely, miserable lives; the promise of being whomever they wanted to be; and of being accepted and loved by America.

At a remove, I’m capable of categorizing the manongs’ behaviors—drinking, gambling, womanizing—as coping mechanisms. But for Dad, who was the youngest of seven, it was traumatizing to witness his father, then his own siblings, inexplicably succumb to the same addictions. He was convinced this inheritance was fatalistic, a disease you could catch by mere proximity, and he became estranged from his family. My father, younger sister, and I eventually did immigrate to the U.S. to reunite with my mother long after Lolo had passed. Yet, his specter still haunts us.

When we first moved to New York, Dad struggled to find work because the multiple advanced degrees he earned in the Philippines weren’t recognized in this country. The pressure of mounting bills and his inability to provide for his family for the first time in his life made him sick to his stomach and gave him frequent headaches and chest pains.

I observed my father go from being angry and resentful to quiet and withdrawn. But, we didn’t talk about his anxiety and depression (or mine, or my sister’s, or my mother’s), because questioning out loud why we had to move away from friends, family, and from Baguio—the only place that’s ever truly been home to us—was to repudiate all of Mom’s work and sacrifices as an Overseas Foreign Worker to bring our family to the U.S.

Lolo thought he’d spare future generations from experiencing the pain and heartbreak of waking up in an American Nightmare by taking his secrets to the grave and forbidding his descendants to uproot and plant ourselves on American soil. But, perhaps, there is reason for our being here in this time. In the past year, Dad and I have been sharing recently surfaced memories and research discoveries about Lolo Pilong’s life.

Over a bowl of soup at our favorite noodle shop in Chinatown, Dad told me that his fondest memory of Lolo was watching him make sopas. Lolo would head to his suki (a vendor he’d built a relationship with as a frequent customer) for soup bones, which he’d throw into a cauldron full of water and let simmer on a slow fire for the entire day.

Dad and his siblings would smell the savory broth while waiting impatiently for Lolo to call out, “Sopas!” as soon as it was ready and make a run for it. “It made you warm,” Dad said, “and there was an exquisite joy in knowing you were the only one having soup while the rest of the world was asleep.”

Dad also opened up to me about what it was really like for him in those early years in New York. He confessed that he had joined our church choir, not for pious reasons, but to learn how to speak English with an American accent so that he could be understood. He attempted to dye his hair from a natural black to a lighter brown, gain an inch in height by wearing thick-heeled shoes, and even contemplated bleaching his skin and getting a nose lift.

“When I was made to feel different and treated differently from others, I began to understand my father’s objections to emigration,” my father said to me. “I realized I hated myself for who I was. And I thought I was educated enough to know differently!”

It pained me to hear a man I revere and look up to speak so self-deprecatingly and not recognize his own personhood and self-worth. But, by sharing his vulnerability, he has shown me the greatest strength.

After all this time, we’re finally working on breaking the silences and forgetting in our family. We’ve come to realize that, in our curated accounting of our family’s migrations, we’ve lost stories of survival and resistance.

And now, more than ever, what we need to find our way forward in these challenging times are our ancestral guides who had survived wars, economic depressions, and deaths brought upon by acts of nature or by man. Recollecting their missing narratives of struggle helps illuminate this moment in history for our community.

In keeping up with the news over the last month, I’ve been caught off-guard by the number of major media outlets—PBS, ProPublica, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Business Insider, the BBC, and The Guardian, among others—which suddenly have turned the spotlight on Filipino healthcare workers (not just nurses, but also hospital porters and orderlies, elder and long-term caregivers, and home health aides). They’ve attempted to measure the value of our community in this crisis through a litany of statistics:

- One in four adult Filipinos in the New York–New Jersey region are employed in the healthcare field;

- Filipinos comprise at least 20 percent of the nursing workforce in California and New York;

- While those of Filipino ancestry make up just one percent of the U.S. population, more than seven percent (or 500,000 workers) are in the hospital and healthcare industries.

- Headlines cry out about the “heavy,” “outsize,” or “staggering” toll on Filipinos on the front lines of the pandemic, “similar to times of war.”

- In mid-May, the Philippine Embassy in Washington, D.C. reported that 137 Filipinos in the U.S. have died from Covid-19, 40 of whom were healthcare workers.

A few articles endeavored to document something about the lives of these fallen modern-day heroes or “bagong bayani”—Daisy Doronila, Araceli Buendia Ilagan, and Susana and Alfredo Pabatao now are household names.

Yet, as political scientist Jean Encinas-Franco of the University of the Philippines cautions, by focusing primarily on the narratives of heroism, sacrifice, and martyrdom, we are in danger of normalizing the export of Filipino labor and its exploitation by wealthier nations and of relinquishing accountability for the workers’ safety and welfare.

The systemic evasion and erasure of the stories of undocumented workers, indentured servitude, racism, contractualism, wage theft, and human rights abuses dooms history to repeat itself.

We must commit to sustaining the visibility of our community, not only by making known our contributions each and every day to this city and this, our country, but also by speaking out and advocating against injustices in and beyond the Filipino community.

In doing so, we may begin to heal from our intergenerational wounds and one day be able to release the Little Brown Brother’s burden—our burden—as Pilipinxs in America.