You settle into the ease of not leaving.

February 28, 2023

I.

He says he hungers for you, sends you

$1000/week, no sex, just company on DM

and you remember the last man you let into

your bed who gripped your ass and asked

if you could wiggle your hips just like that

Kpop singer, that’s right and you remember

when he found you at Blondie’s bar last week

with a beer in hand and stubbled mouth opening

with a grin and the line it should be

illegal for you to exist—and you remember

the way he paused then to take a swig before

finishing—because of how perfect you look.

And when he finishes he rolls off of you and

you curl up on the end of your bed and

somewhere another man’s hunger has just finished

drenching another floor with our blood.

II.

You stay inside until you reek of stale anxiety. You settle into the ease of not leaving. Days bleed into a hazy sameness; cream-colored walls pitch and yawn under eyes adjusted to the indoors. It’s too easy to disappear these days, to have others lose you in the margins of internet and people trying to live their own lives. Once when you used to live with three roommates you squeezed yourself into the back of your closet for a week to see if anyone would notice. No one did. And at the end of the week you were dehydrated and hungry and you remember thinking that if the man from Blondie’s had killed you that night and shoved your corpse under the bed perhaps no one would notice until it began to smell.

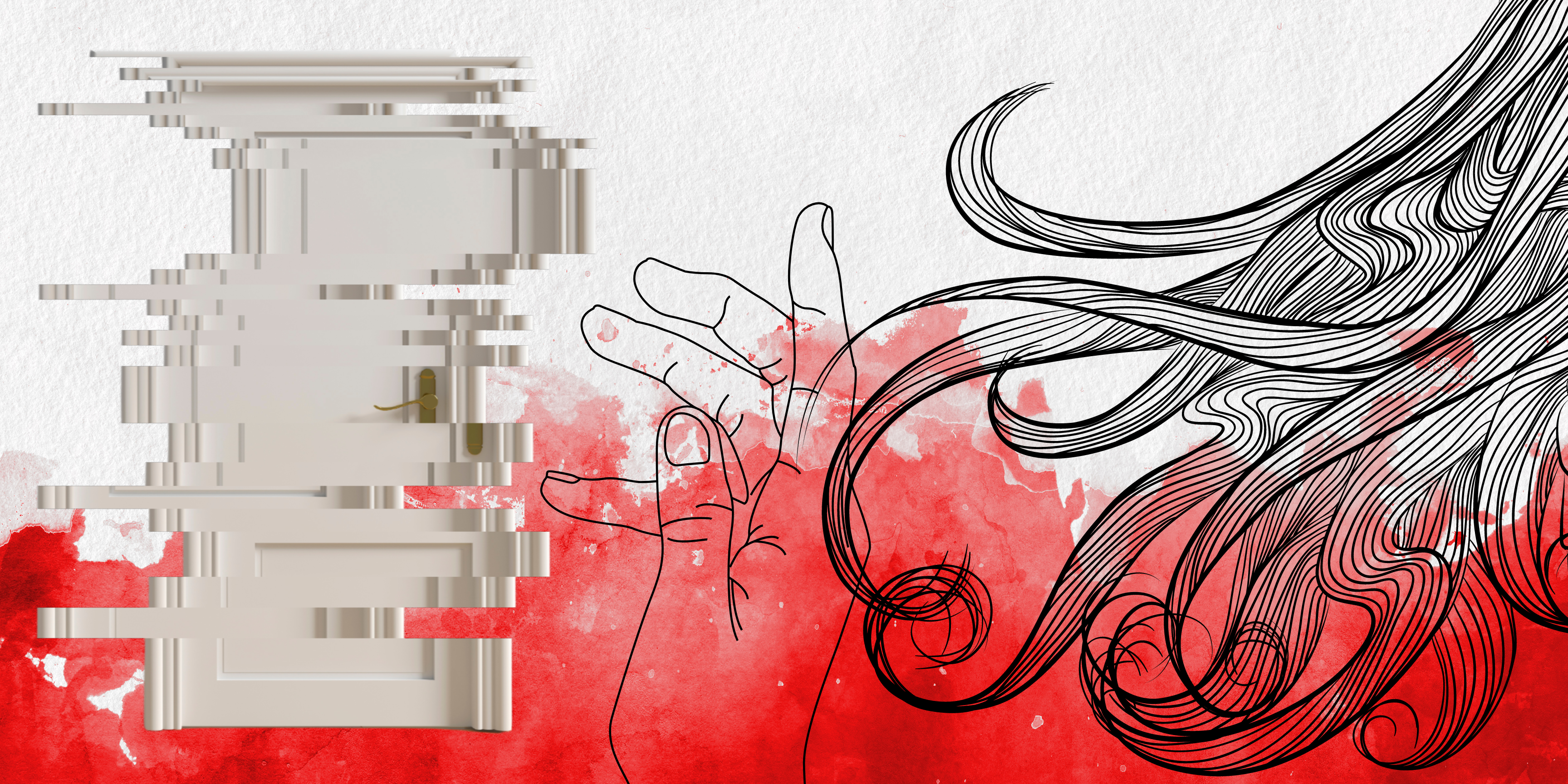

You are young yet you know the world hungers for the way we love, claims to know the way we love. You are afraid of this hunger, the way it cuts, the way it bruises, the way it makes us bleed. You touch the spots on your hips and feel a lingering hurt in the shadows of his fingertips. You dream of the front of barreling subway cars and knives sinking into skin and falling fists and men with guns.

The therapist you meet over video call asks you to describe the thing in you and you try to explain that it’s a drawn-out form, a dissected anatomy of a scream. You ask can you hear that? There’s screaming and screaming and screaming and screaming

and when it ends you are left with a two hundred dollar bill and a one-word explanation (agoraphobia, you look it up later) and homework to at least try to walk once around the block.

The world beckons, open-jawed and hungry. You put on your jacket. You slip the bottle of pepper spray into your pocket. You step into your shoes—beat-up Stan Smiths you found on sale at the Nordstrom Rack on Market Street, which you haven’t visited since the stabbings.

You put your hand on the door. It feels like what it is: a cold looming heaviness between you and the rest of the world. Safe.

Tomorrow, you say to yourself, stepping out of the shoes and lining them back neatly against the wall. Tomorrow.

III.

Your mother loves you in the third person. Mom is home. Mom is calling you. Where are you? Mom is worry. She is third. There is no first. There is only you.

Your mother loves you with gap-toothed sentences, paragraphs she asked you to smooth out in emails she used to send out to her coworkers before she went on permanent disability leave. Mom go to San Francisco. I am trying to go Chinatown. I am Chinatown. Where are you?

Just make sure you ok.

Your mother loves you like she knows the world hungers for us. When will you be home? When will you come home? Where are you? Are you on your way home?

God, I want to stop watching hands in pockets with a precise terror and to wear my black hair down in public and for men to stop splitting our bodies in half as they take, take, take, and I want to carry a torch and set fire to a mountain of guns and to resurrect the dead and to pull the man from Blondie’s up by his stupid man bun and tell him I’m Chinese bitch and I want to walk alone to buy new shoes without hungry eyes following me and I want to trust in love and I want love to always be like my mother’s love and I want to experience the purest type of hunger against my body and most of all

I want my mother to know that every night I will come home safe.