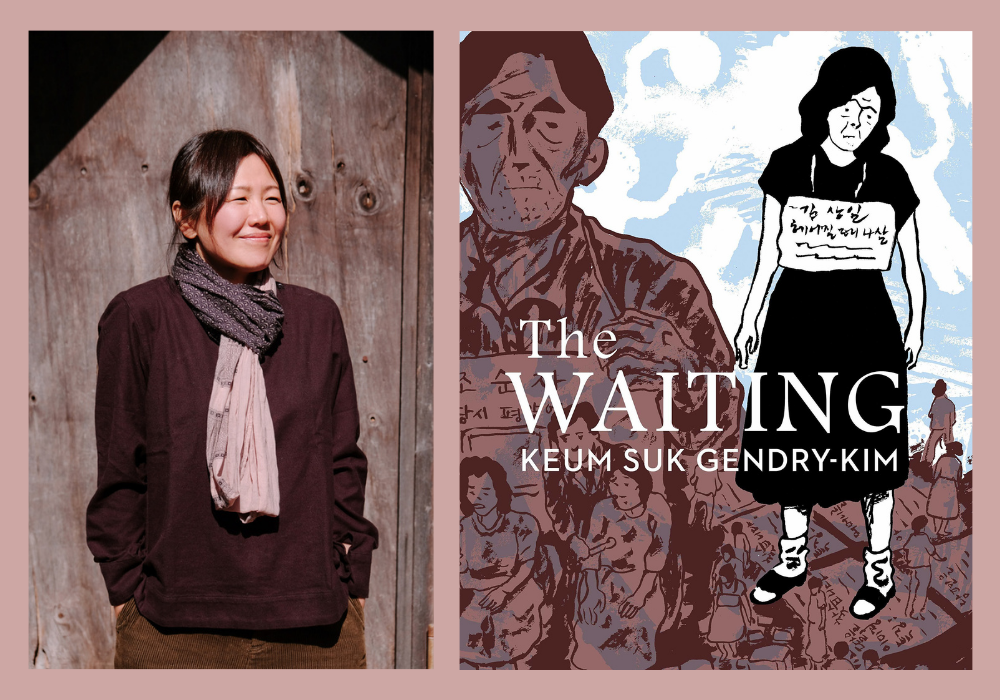

The author of the graphic novel The Waiting on family separation and the Korean War

November 11, 2021

Before she was an award-winning graphic novelist, Keum Suk Gendry-Kim was a painter, a sculptor, a bookbinder, and a translator between Korean and French, living in Paris. She lived there for 17 years before returning to South Korea.

Gendry-Kim was in her late 20s living in Paris, however, when she heard the story that grew into The Waiting (기다림), a moving and dramatic graphic novel of aging, war, family reunions, and separation. Her mother’s story. Her mother was staying with Gendry-Kim in Paris for two months after Gendry-Kim’s father passed away when she revealed a family secret. She had grown up in North Korea and had left behind family—an older sister in Pyongyang, who she desperately wanted to meet again.

The Korean War (1950-1953), which began over 70 years ago, permanently sliced the peninsula into two nations, and the remaining families, separated by the 38th parallel, still wait for a reunion with their loved ones. Gendry-Kim’s The Waiting, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong, explores this ongoing division through the eyes of Jina, a writer, and Song Gwija, her mother.

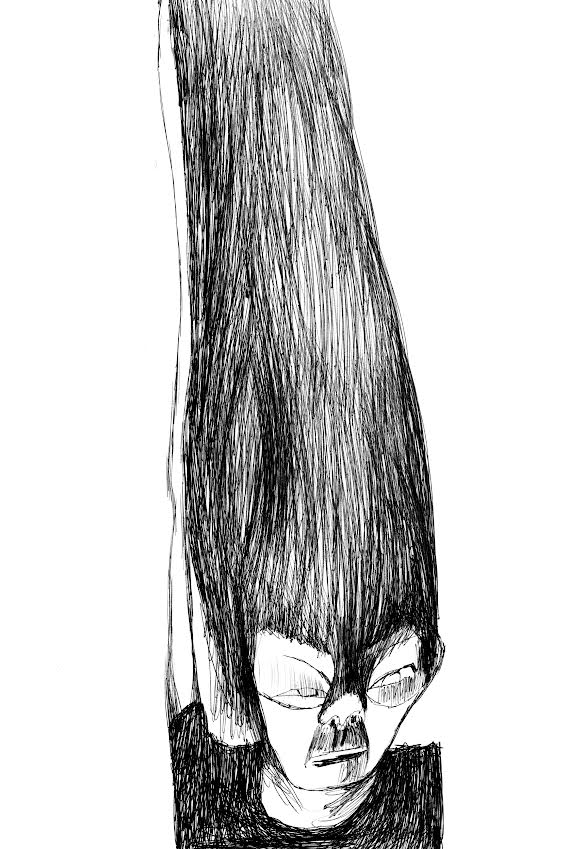

Gendry-Kim’s black-and-white hand drawings of aging Gwija—wrinkles, moles, unibrow, and forehead etched with deep affection—and her lonely life in an apartment in Seoul are poignant. Jina’s guilt over caring for her ailing mother, still stuck with a wartime mentality, is palpable. But the impossible promise to reunite her mother with her first son, Jina’s half brother, lost to the north, weighs heaviest. Of course, it’s not an uncommon story. An estimated 2 million civilians died during the war, and hundreds of thousands of Korean families remain divided. A generation of people well into their 80s and 90s who remember an undivided peninsula is dying out. Some hope against hope to be selected via a government lottery system for a meeting, however brief, with their family members.

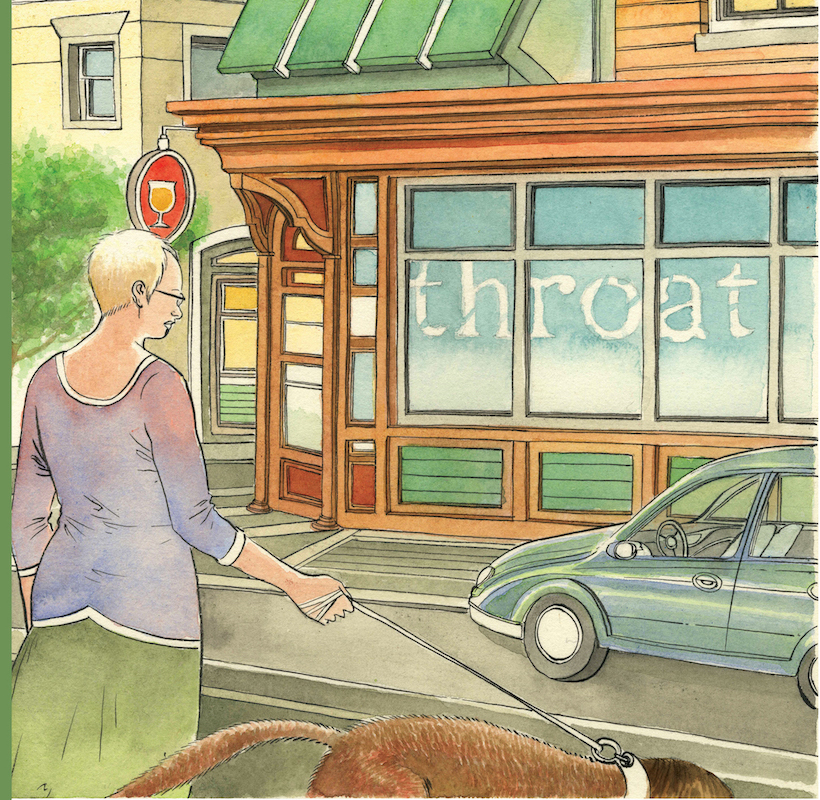

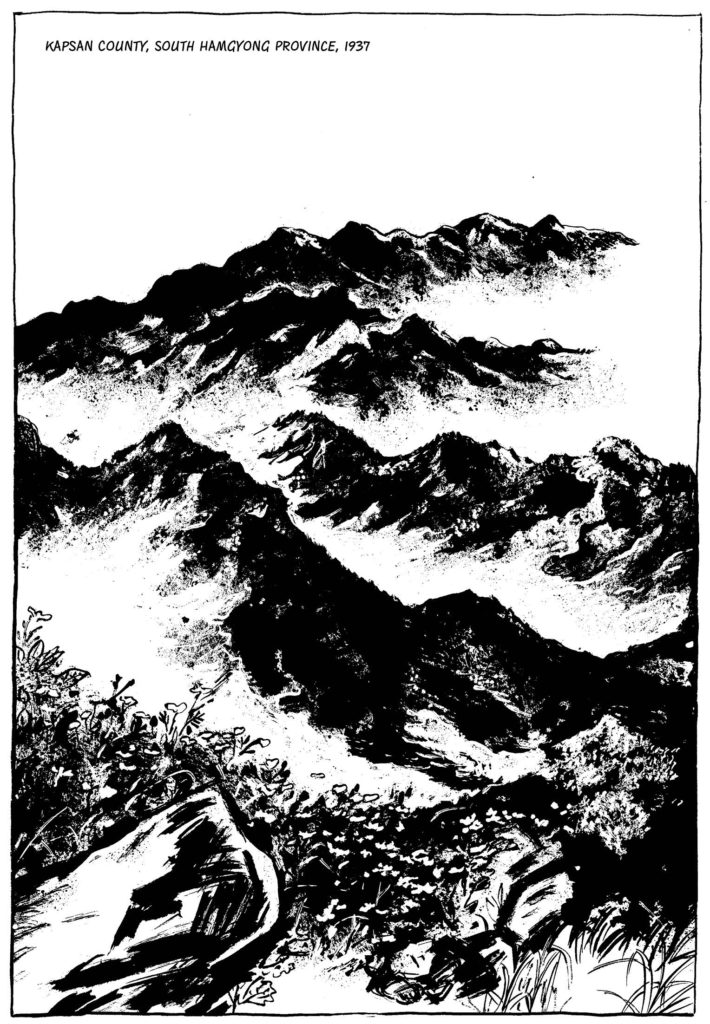

Gendry-Kim’s English-language debut, Grass (풀), which told the story of sex slavery (comfort women), won the Krause Essay Prize, the Cartoonist Studio Prize, the Harvey Award, and appeared on best-of-the-year lists from the New York Times, the Guardian, Library Journal, and more. The Waiting, which came out last week from Drawn & Quarterly, is an important follow-up. Of all Gendry-Kim’s stories and images in this graphic novel, the most striking is the quiet view from a high, grassy lookout over cloud-swept mountains. Populated with people, her drawings are like etchings—scratched, frenetic lines with pools of ink on the page—but this mountain scene is soft and empty of humans. Korea’s old myths revolve around its mountains, so the mountains can make one homesick. The caption tells us this is Kapsan County, South Hamgyong Province, 1937, in the calm before the storm—land that used to be Song Gwija’s home.

Over email, Gendry-Kim and I discussed the evolution of The Waiting, her past lives in France, and the artist who inspires her today.

—Esther Kim

Esther Kim

Earlier this year, you spoke with Emily Jungmin Yoon (The Margins’s longtime poetry editor) for Korean Literature Now and mentioned that you came up with the idea for The Waiting in 1999! The Waiting published in South Korea last year and has since been translated into many languages, including English, French, Portuguese, Italian, and Arabic. I imagine in that long process, there were multiple versions. Tell us about the evolution of The Waiting. What were some stories or versions that you changed or decided to scrap?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

In 1999, when I first heard the story of my mother and her family, I found it captivating, perhaps even more so because I never knew my grandparents on either side of the family. She told me all about her childhood and marriage to my father. It was fascinating. This was at a time in my life when I was questioning my identity and my roots. Something about living in France for so long had pushed me into this self-reflection. All of this is why I started recording my mother’s memories.

Part of what I recorded touched on life in North Korea and my mother’s elder sister who stayed behind when she left. At the time I didn’t think I would make a graphic novel about it, but the more time passed, the more I knew I wanted to tell this story. Because her story was intimate and specific to her but also universal. At first, I wanted to recount [my mother’s] experiences, beginning with her parents’ lives. I was thinking I should be faithful to the testimony I had recorded. But when I started with that premise in mind, I realized the only way I could do so faithfully would be to make a whole series, not a single book. So I decided to focus on the Division of Korea, the generation that lived through the war, and the generation that didn’t know what living through that war meant.

EK

When I finished The Waiting, I was surprised to find that the story was fictional. I mistook it for completely autobiographical—probably because one main character, the daughter, is a writer too—until I reached your author’s note at the end. What research did you undertake for The Waiting?

KSGK

The Waiting is partially my mother’s own story. I couldn’t be 100 percent faithful to her experiences because I wanted to protect my family and myself. So I decided to interview two people who were reunited with their families. I combined those interviews with the testimony of a friend’s mother and the testimonies I found in other works, and all these sources helped me shape the story.

EK

The ongoing division between North and South Korea affects Koreans across the globe, including my family personally. In South Korea, the topic of reunification is a political minefield because it touches on questions of nuclear disarmament and communist sympathies. But at base, there are so many who simply long to reunite with their family members and see their hometowns. What is your hope for the future of the peninsula?

KSGK

Hope… There are a lot of complications and complexity when it comes to reunification. Despite all that, I hope that it happens as quickly as possible. The longer we have to wait, the harder it will be.

EK

You lived in Paris, France, as a painter, sculptor, and bookbinder for many years. The way you fell into drawing graphic novels seems like a happy accident. That is, you supported yourself by translating Korean graphic novels into French and translated nearly a hundred! What was the French appetite for Korean manhwa like back when you started in the 1990s, and have you seen changes?

KSGK

Korean comics (one-off graphic novels and longer series) started to be acquired by French publishers at the beginning of the 2000s. At first, French editors were buying a lot of every kind of title, because they thought that it would sell the way manga does. That wave lasted a few years, and even led to the foundation of dedicated manhwa publishers. But when they realized that manhwa wasn’t going to sell in the same numbers as manga, a number of series were canceled and the publishers shuttered. Nonetheless, certain independent publishers continued to put out Korean graphic novels that were more “artistic” and dealt with more serious subject matter about society, history, or more intimate stories. In other words, the publishers who had always put quality ahead of quantity when deciding what to acquire continue to publish Korean authors.

EK

And how have French graphic novels, comics, or illustration influenced your work (if at all)?

KSGK

The range of artistic styles and the freedom of expression in France made me understand that there isn’t a set of rules you need to follow when making a graphic novel. The most important thing is that I do what I want, to the best of my ability.

EK

Your works tackle historical events of great violence, such as sexual slavery (comfort women) in Grass and now the Korean War in The Waiting. What is the role of an artist in documenting history?

KSGK

Of course I speak about the violence that took place in Korean history. But with these stories, I am able to show the resilience of the people who lived through these hardships. The themes of all my books are connected. My parents lived through these events—sometimes intimately, sometimes just by being alive—and I come from them.

Recently, I was invited to Belgium and France to participate in events and book signings. The people who came to these events told me that because of my books they were able to learn about important historical events that had been hidden or swept under the rug. According to them, the historical events I write about do not appear in textbooks. And they told me that they were very touched by my work. I think maybe that is the answer to this question about the role of an artist.

EK

Lastly, who are the artists and writers that inspire you today?

KSGK

Nature is the most incredible artist. Right now, my inspiration is autumn and the stars 🙂

Translated between the French and English by Julia Pohl-Miranda.