និស្វាសវាត / អស្សាសវាត / បស្សាសនៃ / ខ្យល់ចេញមិនចូល | In, out, held – / so goes the breath. / Winds leave but no longer come

March 15, 2021

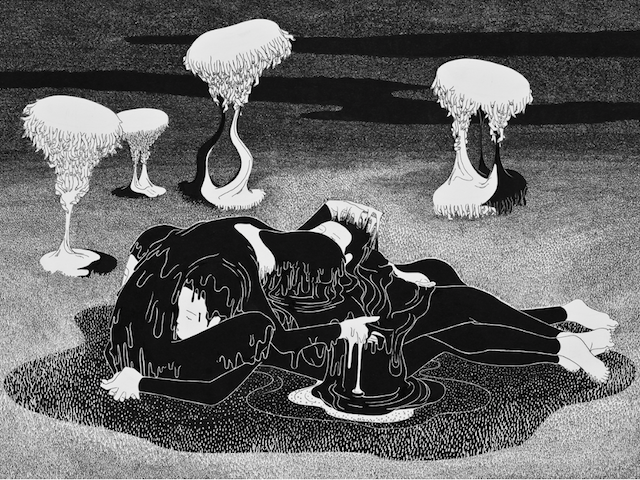

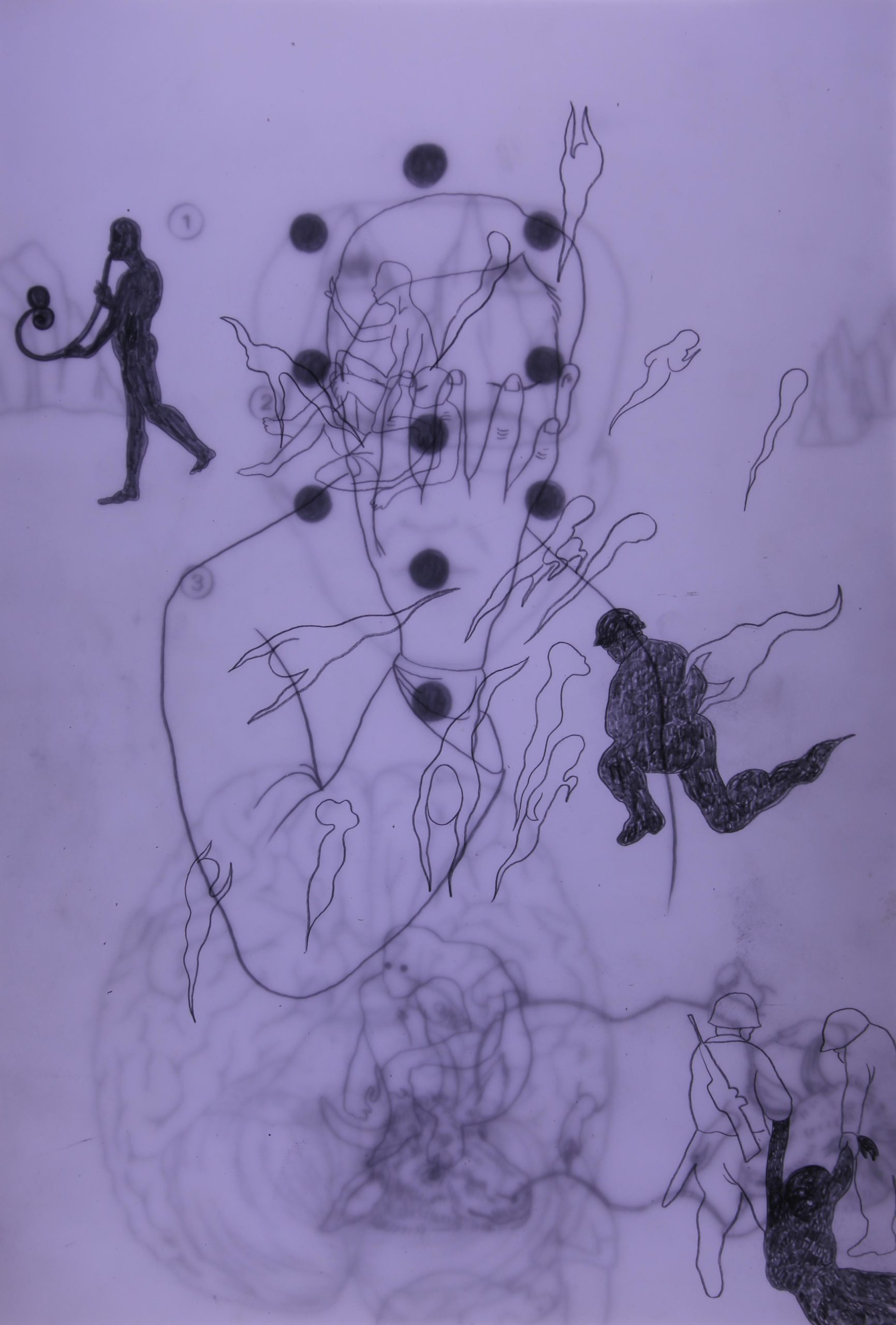

Editor’s Note: Today’s chant-poem is part of a notebook of Lullabies published by the Transpacific Literary Project. Each piece of the notebook is paired with a pencil drawing by the artist Trương Công Tùng. Read the other Lullabies in this notebook here.

Click to read Trent Walker’s English translation below

រូបក្ខន្ធោ

This Heap Called a Body

You’re no different.You’ve got one too:

this heap called a body,

liquids, solids, a source of heat,

two ears, two eyes, and a tongue.

But heaps don’t last.

You’ll die in pain,

pummeled senseless

and bound in chains

by Death’s little men.

Your breath goes first,

down the body, through the palms,

out the soles. Winded,

you plead with your captors

for one last talk with your kids.

But Death’s minions,

full of rage, won’t let you go.

They curse you: Damn thief!

You think you can cheat death

without seeking the path of saints?

When your time’s up,

make a pledge and we’ll assent.

But don’t you dare

talk back to us –

no last words for now.

Death, waiting in the wings,

swoops in to seal your doors.

Closed off, you cry inside,

Mom! Dad! Save me!

Show some love for your child!

shall be cast away,

or so the scriptures say.

Your fever spikes, your breath quickens,

letting out more than you take in.

You try to turn back,

and shout with muffled tones,

calling out for your family.

You might recover enough

to give your final will.

Yet karma soon resumes its course.

You gasp for air. Your body goes slack

as you lay weak, helpless on your bed.

Others may feel for your pain,

but what can they really do?

Loved ones gather, kids and kindred souls,

their hoarse throats lined with prayer.

They slot a coin through your lips,

a gift for worlds to come, yet nothing

they do can halt this march of death.

so goes the breath.

Winds leave but no longer come.

Veins and vessels twist and twirl

as life sighs into death.

Your body is orphaned,

lonely, unguarded.

The soul within wanders,

bereft of a body.

A ghost takes shape and leaves.

Unconscious, unmoored,

this specter laughs without a care.

Men shoulder your corpse

deep into the woods,

and score a cross in the soil.

Your ghost frolics, heedless, headless,

but soon pines for its old abode.

Floating off to the forest

it finds the cross, and at the crossroads,

byways blocked by thorns.

Your ghost pauses, then wonders aloud,

Who dared to call me dead?

Look! They’ve laid out brambles

and carved an X in the earth,

blocking my escape.

And look at my fingers!

Before I had five on each hand,

but now I’m down to four.

In fear, it cries, Mom! Dad!

Why have you thrown me away?

You hate me, don’t you?

Why not keep me at home,

or bury me in your yard?

You didn’t say you’d dump me

out here in the wilderness.

Help me, Mom! Save me

from this den of savage beasts.

Here, far from human life,

the fleshy eyes of owls

track my every move.

The woods lie still and hush,

prowled by tigers and wolves,

elephants and dholes,

monkeys and packs of dogs.

My carcass lies there, alone.

stamping its mark in the earth

from daybreak to noon

in the fearful forest,

forlorn and flooded with tears.

Your ghost sits by your grave,

bemoaning its former host.

This swelling flesh,

those bulging eyes!

The neck sinks down,

the limbs splay wide,

the trunk splits open.

Blood flows from all nine holes,

staining the body,

soaking the soil.

After seven days,

sinews break apart,

leaving only bones.

All falls away,

no body remains.

Soon, for your ghost,

only pain endures,

days and months

of hunger and lack,

a wake of misery.

Your kin cover the corpse

with a thin cotton shroud.

And so your ghost wanders

to beg from strangers

until your bones bleach white.

a tale of hundreds of thousands of lives.

Hear this, dear friend, and be stirred.

Study the virtues within your body

that lead to freedom from pain.

Don’t get caught in suffering;

move on, let go, find peace.

While you’re still alive,

change your own fate,

for karma cuts through all.

Hold to what’s good,

cultivate yourself,

keep wise words on your lips.

Forsake your wealth; just give it away.

Don’t be greedy or grieve past gifts.

Keep your eye on the highest truth,

keep your patience, keep your vows.

Help others and live with thanks.

Adore the seeds you sow,

a basis for future boons.

Death himself will grant you favor,

the gods will rejoice and lift you high.

You’ll rise to the heavens above,

dodging the hells below

and other stations of woe.

listen close to this advice.

These teachings aren’t easy,

but they are the bud

that blooms in bliss.

Rare are these words,

and rarer those who take heed.

For death is sure for all who are born.

You’ll lose everything, carts and chests,

priceless bracelets and wish-granting gems.

You’ll be parted from all that,

save for a mouthful of betel

and a silver round, pushed between your lips.

You’ll even lose that single coin,

for once you’re gone, they’ll snatch it back.

Strive hard while this body remains.

Perfect your conduct, give with abandon,

bridge the ocean of birth and death.

Etch your prayers deep in your chest

and point the mind to lasting peace.

Translator’s note:

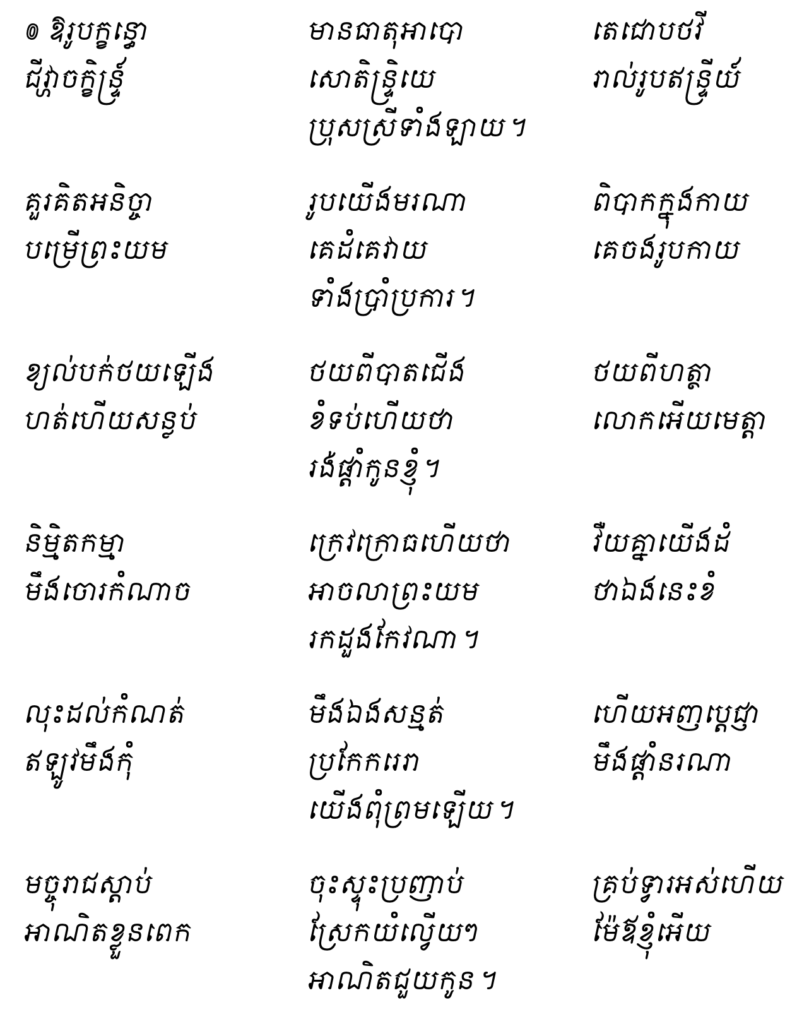

The above poems are a Khmer-language edition and English translation of a traditional Cambodian chant, រូបក្ខន្ធោ | “This Heap Called a Body”. This particular chant belongs to a tradition known as smot ស្មូត្រ or Dharma songs ធម៌បទ: poems recited in flowing, expressive melodies in Buddhist ceremonies. They have a special association with accompanying the dying as they pass into the next world. In this context, such chants are sometimes known as “lullabies for the end of life” បំពេចុងក្រោយ. Just as we enter the world with tears and song, so too may we depart.

រូបក្ខន្ធោ | “This Heap Called a Body” is found in a few leporello manuscripts or ក្រាំង, an accordion-folded bark-paper format commonly used for collections of end-of-life chants in Cambodia. The Khmer text of the chant has been edited on the basis of four such leporellos. Though neither the date of composition nor the name of the author is known, the context and style of these stanzas suggest they were first penned in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. Other poems in this genre were copied by hand or transmitted orally for generations. The oldest leporello containing this particular poem, however, only dates to 1961, and belongs to the collection of Mr. Man Phu លោកតា ម៉ាន ភូ in Thlok Trabaek ថ្លុកត្របែក village, Kandal province, whom the translator visited in 2016.

Each of the surviving manuscripts gives a different title for this text, though most give a variant of rūpakkhandho រូបក្ខន្ធោ, a Pali-language compound meaning “the aggregate (khandha ខន្ធ) of form (rūpa រូប).” It refers to the physical body as a distinct “aggregate” or “heap” of life, as opposed to our mental and emotional experience of the world; hence the translated title, “This Heap Called a Body.” Each stanza in the Khmer text consists of seven lines of four syllables each, locked in a series of linking rhymes (បទកាកគតិ). The English translation follows a freer format, with stanzas of five lines each but no further metrical constraints.

Unlike Khmer lullabies for the young, “This Heap Called a Body” is not meant to be soothing. Rather, it is meant to stir the listeners—particularly the sick, the dying, and their companions—out of their complacency. The poem speaks frankly of the horrors of death itself as well as the difficulties our own departed spirit will face after the body collapses. True to its eighteenth- or nineteenth-century composition, this chant portrays an old form of Cambodian mortuary practices, namely the disposal of corpses in the forest, where they become food for carnivorous scavengers. This lullaby seeks to haunt the living, to wake people from the dream that life extends forever, that death is painless, and that attachments are easily shed.

To read and listen to more Cambodian Dharma songs, visit Stirring and Stilling, a multimedia online book compiled by the translator.