The limits of empathizing with your occupier

One of my earliest memories is of my mother calling my aunt, who was in the United States at the time, to tell her that two of their cousins were shot by the Israeli army, but the third survived because he splashed their blood on his body and laid still until the soldiers left. I remember hearing screams from the other end of the phone. Later that day I placed an imaginary call to my aunt to tell her that I put bandages on them, and they are okay now. I was five years old.

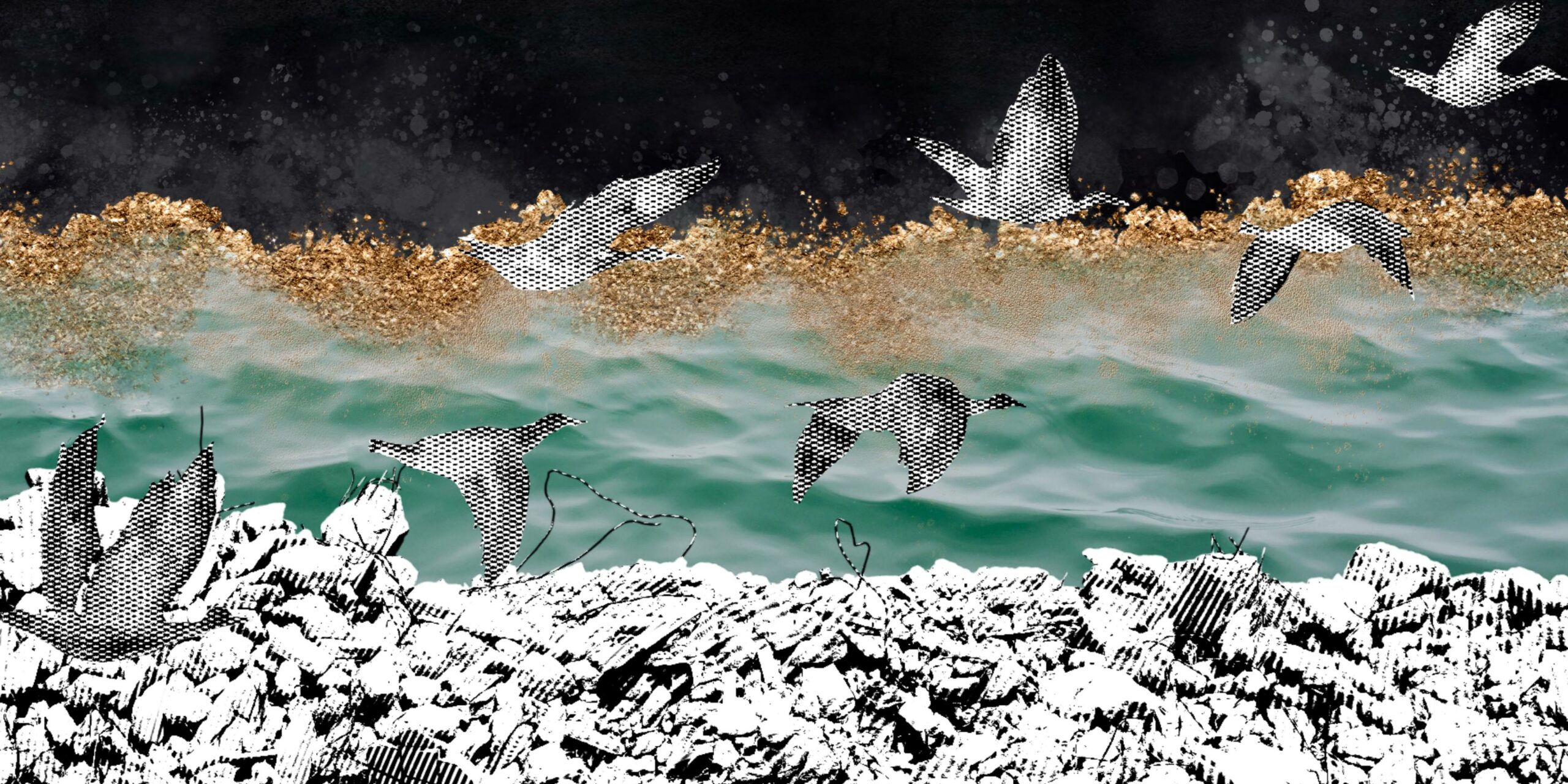

When I was putting my daughter to bed last night, I sang to her a song my father used to sing to me: “I wish my body was a bridge that you can safely walk on, and we can live together in freedom in Palestine.” As I put her in her crib, in her safe room in Brooklyn, I thought that her safety was completely arbitrary, a pure accident of birth. I could have easily been putting her in her crib in Gaza, knowing that she, or I, or both of us might never see the light of day again, might never have another morning together, might be getting pulled from the rubble of Gaza as we speak.

I grew up in Palestine. As a child, I experienced nonsensical and unspeakable violence, too much to write or speak about. But my mother used to always tell me that our own self-liberation comes from humanizing our occupier, and their biggest defeat will always come from their systemic and intentional dehumanization of us. Considering how my mother had to grow up, that feels like an impossible feat, but somehow, she managed to practice what she preached.

When a herd of Israeli soldiers stormed our home during the second intifada and put us all in one room with an AK-47 pointed at us, my mother asked the soldier pointing the gun about how he was feeling and if he missed his family. She asked him if he was going to be able to go to college and said that she hoped that he could go back to his mother soon.

When she was diagnosed with cancer and had to cross a checkpoint on foot, to receive treatment at an Israeli hospital (since Israel doesn’t allow Palestinians to have access to chemotherapy), she befriended all the Israeli doctors and nurses, and used to say that she looked forward to going because they served the best cheese sandwiches. After every blood transfusion, she would also say that “now she has Israeli blood in her.”

When my mother died at that same hospital, we had to wait for hours for them to find an “Arab” doctor to sign her body out, because her brown Arab body wasn’t fit for an Israeli doctor to process. If my mom had been there at that moment, she would have said that it’s okay, because they just didn’t know any better.

I think my mother would be upset with me right now, because I’m finding it very difficult to empathize with my occupier. I am ashamed that when I first heard that there were Israeli casualties in October, my first thought was that maybe now they can understand how we have felt for seventy-five years, how we have been oppressed, killed, dehumanized, maimed, suffocated, kidnapped, jailed, and bombed. Maybe if they understood, they would stop, but empathy is not a symptom of war, neither is nuance, because the idea that all Palestinians are Hamas supporters is not only wildly inaccurate but dehumanizing and dangerous.

Make no mistake, we are probably one of the few who understand how a lot of Jewish people might feel right now, with their collective trauma resurfacing and nightmarish images of gas chambers and intentional annihilation for decades flashing before their eyes with rawness, as a confirmation that they will always be persecuted as a result of their religion and culture. But if you are perpetuating violence against Palestinians from your comfortable and safe homes in the West, you are personally participating in the continued unsafety and instability of your fellow Israeli Jews. It has become clear that Israelis will only live in peace when Palestinians are afforded the same luxury, and that the constant oppression of another people is not an appropriate or productive trauma response.

When I was seven years old, I remember my mother falling to the floor when she heard that twenty-eight Palestinians were shot by an Israeli settler as they knelt during morning prayers in a mosque in Hebron. Today, I hide my tears from my daughter when I look at images of Palestinian babies, who look exactly like her, being pulled from the rubble. Generations of Palestinian grief are not enough to convince the Western world that we are humans too, that we also deserve freedom, dignity, and a chance at joy.

I have been wondering how many dead children are enough for this incomprehensible violence against Palestinians to stop, for the Israeli government to feel satisfied and for its murderous rage to quell, even if just for a little bit, to give families a chance to bury their dead—but I keep forgetting that to them we all deserve to die, and after they kill us all, they will kill our animals, trees, and inanimate objects. That thought fills me with sadness for them. Can you imagine what has to happen to your core to become like that? Can you imagine the nightmare that is your life when you feel this way about other people?

My only solace comes from the words of James Baldwin, from his letter to his nephew, where he wrote: “Those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them safe are losing their grasp of reality. But these men are your brothers, your lost younger brothers, and if the word ‘integration’ means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.”

I will, for the sake of my mother, pray for their children, who are just as precious as mine, and dream of a day when we are all free.