“The work of journalism is bound up in paying attention and noticing things. That’s kind of how I go through the world, with an antenna up for the unexpected, the beautiful, or the moving.”

April 5, 2021

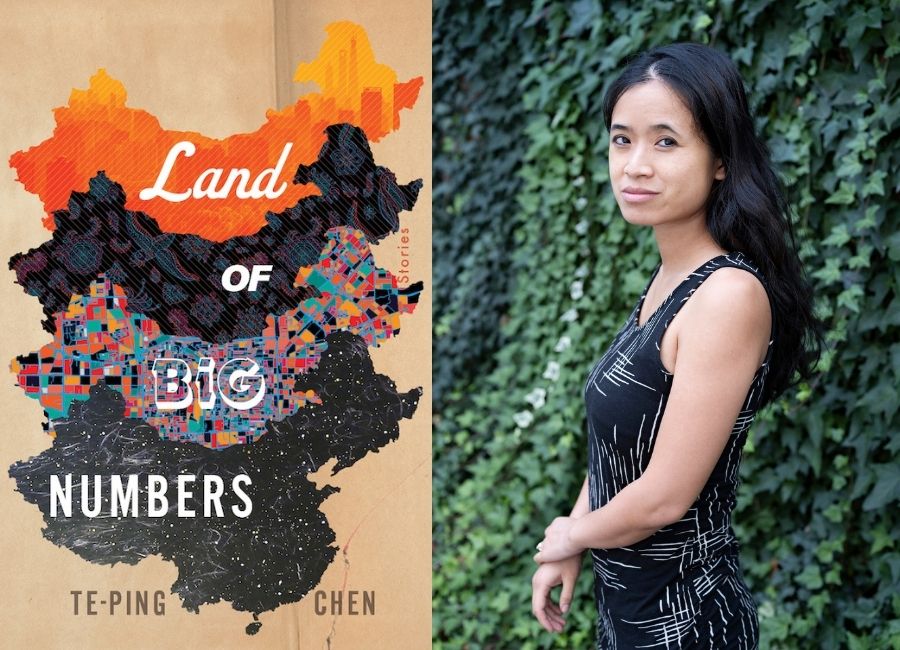

In Te-Ping Chen’s debut collection, Land of Big Numbers, rural airplane inventors collide with party bureaucrats, a neighborhood gets swept up in a magical fruit craze that unearths painful collective memories, and train passengers trapped in a subway station get so comfortable they become reluctant to leave. Reading this vibrant, cacophonous collection, I’m reminded of Italo Calvino’s definition of literature as an encounter where “various levels of reality may meet while remaining distinct and separate, or else melt and mingle and knit together, achieving a harmony among their contradictions or else forming an explosive mixture.”

Levels of reality abound in Chen’s stories, personal histories melding with repressed collective trauma, intimate love stories bumping up against the reality of crass commercialism, realism itself slipping—irrevocably, if barely noticeably—into the surreal. What binds these stories is Chen’s voice: confident, playful, boundlessly compassionate. A journalist by trade, Te-Ping Chen was the Wall Street Journal’s Beijing-based China correspondent from 2014 to 2018. With a sharp eye for detail and a sly sense of humor, Chen takes on the big questions of freedom, history, longing, an individual’s place in society. I had the opportunity to talk to Chen over Zoom about hauntings, journalism, and her writing process.

—Rachel Heng

Rachel Heng: In the story “New Fruit,” we’re told of the character Pang Ayi: “What other people saw as a gossip’s instinct was really a fierce desire simply to notice things, to see the possibilities in things and what they meant, whether it was a certain expression that flitted across a neighbor’s face or a flock of starlings on the roof.” I love this notion of “a gossip’s instinct,” and this careful noticing is what makes so many of these stories come alive so vividly. How do you cultivate your gossip’s instinct as a fiction writer and journalist?

Te-Ping Chen: I always feel like the worst gossip in the world, so the skills that Pang Ayi has, I don’t necessarily feel like I have them. She’s a character that I loved getting into. I’m really pleased that you picked up on that line, because it’s true, I think there are so many ways where the work of journalism is bound up in paying attention and noticing things. That’s kind of how I just go through the world, with an antenna up for the unexpected, the beautiful, or the moving. Some of that definitely came through in my journalism and many things couldn’t, which ended up fueling the writing of Land of Big Numbers.

RH: How do you decide if something becomes a journalistic piece or a piece of fiction?

TPC: With the journalism, you really did have to run the gauntlet of: is this urgent, is this meaningful to a global audience, and often, is it relevant to a U.S. context too. So, often those stories were kind of dictated for you. Just the news. In the time I was in China, there was Donald Trump’s election and the U.S.-China trade war, not to mention all the incessant news on the China home front, from the crackdown on human rights lawyers, to the increasing ideological tightening in universities, to efforts to clean up the environment. So many stories just had to be covered, because news is news. To some extent, I was able to write stories that I felt did capture that side of China that’s more human and vivid, perhaps more unexpected. I did one about the government’s push to propagandize potatoes and to make potatoes a big part of people’s diet. There was a woman who wrote songs about potatoes that were performed on state television. I also wrote about “meat rock” collectors—people who collect rocks that look like meat. And so, there were ways that I was able to utilize that eye for character detail in some of my reporting.

RH: And how about the other way round? What would spark a short story for you?

TPC: Oh wow, everything. I feel like I was always just having ideas, and part of the challenge was whittling them down. “Flying Machine” for example, the one about the rural farmer who wants to build an airplane, that was a recurring headline I kept encountering in the local media about these rural inventors. These were often farmers who weren’t educated and had these amazing passion projects, everything from building life-size transformers to airplanes. Funeral strippers were another thing I encountered through my work. I still remember, it was late in the day in the bureau, and we saw that the Ministry of Culture had put out a circular, saying they were going to crack down on funeral strippers. And I remember sitting there reading that, thinking, wait, what?

But the stories really could be drawn from my own life as well. “New Fruit” was inspired by my neighborhood, in particular the nectarines that were sold every summer, which were just so incredibly delicious. I wanted to focus on this old hutong neighborhood where I lived and which represented a very special part of Beijing. And “Lulu” came in part from when I was reporting a story about human rights lawyers, and they told me about this young woman whose mother had died after being beaten by the police several years beforehand. This woman had kept her mother’s body in cold storage at the morgue because she wanted to keep the evidence. That really stayed with me.

RH: Something else that really struck me about your collection—like with this story of the woman who kept the body of her mother in the morgue for years—is you’re often dealing with big, difficult, often political or historical subject matter. But there is a quiet humor to all your writing, a careful chronicling of absurdity. Just to name one of my favorite moments, in “Land of Big Numbers,” as Zhu Feng is contemplating his financial demise, we segue into a description of the martial arts show Zhu Feng’s elderly father is watching: “men flying backward in the sky, their crouches and kicks rewound and shown in reverse, knives going backward and landing neatly in their holsters. A woman clad in gray with her hair in a topknot stood making hysterical noises as they flew around, calling: Wei-yuan! Wei-yuen!” It’s hilarious and also somehow very sad because we know what Zhu Feng is going through. Can you talk about the role of humor in your writing?

TPC: I’m so glad to hear you say that, and as a reader, you pick up on that so well. To me, the story of modern China is by necessity grappling with the political context, but so much of the love I have for China and so much of my experience there was rooted in a deep sense of humor and a sense of playfulness of the people I encountered. That’s something I wanted to try to capture. There are so many moments that were a mixture of absurdity and nobility and aspiration. All these contrasts, of what is sometimes really trite, crass commercialism, or really canned forms of entertainment on state media, that then are juxtaposed against the real bread-and-butter tribulations and emotions people are dealing with, whether it’s Zhu Feng and his father, you know, dealing with these interstitial family relationships or just a young woman’s own personal journey. And it felt really important to me to try to evoke that contrast and lightness. I think so often when some people think of China, they think of it as this really dark place, hidden behind the great firewall, and all these voices within that are yearning to be free, and the reality is much more complex than that. I really hope that the book was able to capture some of those complexities and nuances. It’s a country where there is so much joy and beauty and humor to be found.

RH: Speaking of contrasts, thinking about realism and magical realism—I’m curious if you know when you start a story what mode it’s going to be in, and how you decide?

TPC: The answer’s no because the wonderful thing about fiction for me is bound up in not knowing where you’re going. It’s more about taking an image or something I had seen or heard, then trying to unspool from there. With magical realism, likewise. I didn’t want it to feel too much like an absurdist sledgehammer or blunt instrument. I wanted the magic to seep in in ways that were almost undetectable. Like you’re taking a train journey and suddenly you look up at the landscape and it is transfigured. But it happened gradually, in that there wasn’t a sharp break in the journey. For example, in “Gubeikou Spirit,” that’s a story that started from a really realist premise, when I was looking around at the people on the subway one day and thinking, what if we just got stuck? And as I was writing it, it gradually became more distorted, more surreal. It was unexpected for me too as the writer, and that’s what I hope for the reader, that there are surprises in the story.

RH: What was it like putting the collection together? What was the writing process like?

TPC: I was trying to revise a novel prior to writing these stories and ended up getting stuck. So for me, short stories were a chance to play, and to feel a sense of buoyancy, getting to start something new. A lot of the writing process was setting myself challenges. “New Fruit” is written in the choral “we,” which was something I wanted to try to do, and seemed like a natural thing for this omniscient hutong perspective, where everyone’s watching who’s coming and going in the neighborhood. And in some of the stories I was conscious of wanting to write characters that were, for me, very difficult to access in some ways.

RH: Did all the stories make it into the collection?

TPC: No, there were a couple that fell out. There’s one that would be fun now to retrieve called “The China Syndrome” and it’s about a really contagious disease. Starts in Southern China then ends up jumping across the Pacific on an airplane, then it spreads all over the globe. It took on this life of its own, like suddenly there was a global pandemic, and it was a fun thought exercise, figuring out what would happen. The economy shuts down, people start working from home and using apps for whatever they need, and so on.

RH: As much as this collection is about the future—about progress and the opportunities offered by China’s economic boom and those left behind in spite of it— it is also about the troubled, violent past, both on a societal level and in the personal histories of many of the characters. There is a powerful quality of haunting to these stories. Can you speak to that?

TPC: I think I came from a family that was a bit haunted. I don’t know if that tends to be a bit more of an immigrant trait, but my father was always talking about the past and the past always exerted a really strong psychological pull on me, even more so coming to China. I remember my first encounter with Beijing, feeling like this was a place where history had been completely obliterated or reconstructed to the point where it was no longer recognizable. I spent a lot of my early years in the country thinking about history and how it’s ultimately forgotten or resurrected in ways that are advantageous to the party or to tourism or the ways the past could be marketed. It wasn’t something that I wanted to address head-on in the stories because that’s something so many authors have written about in a Chinese context so well. Instead, it seeped in, because how could it not. Such an enormous part of the psychic weight of modern China today is how the past has or has not been dealt with. That’s why in “New Fruit,” and also in the title story, “Land of Big Numbers,” we meet characters that have their own hidden past, that also felt meaningful for me to convey. The feeling of historical amnesia on a societal level, yes, but also it always fascinates me how as individuals, we repress or distort or try and reframe our own histories.

RH: As a Singaporean writer living in the US, writing about Singapore, I’m often thinking about questions of who my audience is, and what level of access my writing grants to its setting, its culture. How do you think about audience in your writing?

TPC: As a journalist, I spend so much time thinking about audience. Fiction felt like a chance to not write with the same kind of halter on. A lot of the joy was in getting to feel like the writing of these stories was a very private act, one that didn’t involve trying to inform or educate or explain to some imaginary audience. Which is oftentimes what a journalist is trying to do. Just the fact that in fiction, you can conjure a world into being, and you can people it and populate it and fill it with references that you don’t need to explain or footnote or contextualize. You just create the world and invite the reader in. You hope it’s explicable of course. But compared to journalism, I had no feeling of having to handhold in the same way, and really gratefully so.

RH: I get that about privacy. I often find with much of my writing, Western editors might ask what does this mean, or what are they doing, or why? But while you grapple with that in edits, in the writing stage I’m writing more toward someone like myself, someone who understands my references and context without explanation.

TPC: Yeah, I felt really fortunate in Land of Big Numbers that that didn’t really come up with my editor. There’s only one moment where it did. At the end of “Hotline Girl,” we learn that the character is working in what’s alluded to as “Transport,” something that sounds really mundane, but eventually the reader learns it has more disturbing resonances. There’s a scene of these protestors, or what in Beijing we would call petitioners, being bundled away. I hadn’t used the word protestors originally in the text because it felt so obvious to me who those people were, and so I described the scene a little more elliptically. But my editor asked about it and it didn’t feel intrusive to change that, to make sure the reader understands.

RH: And how do you think of what words to translate and what not to? I’m thinking of qi guo, ji qi ren—elsewhere, a protestor calls Zhu Feng “handsome brother” (shuai ge), but that’s written in translation.

TPC: I guess I did translate it because I was thinking of the reader and wanting to convey that this was the feeling that she was conveying, and if you said shuai ge it wouldn’t make sense to people who don’t know the meaning of the term. In “New Fruit,” I didn’t translate “bao an.” Because he’s like, the bao an. I mean what would you call him, security guard? I guess you could call him that. But that would totally overstate the role. In a US context it conjures up a different image, it just didn’t feel quite right. Bao an sounded more intimate to me than security guard, which carried different connotations. And there were times when I just wanted the sounds of the words in there. I don’t think I indulged too often, because you don’t want language as scenery.

Want to hear from from Te-Ping Chen? Watch AAWW’s February 21st event with Te-Ping and Charles Yu on our YouTube channel here.