What the marginalization of Asian Americans in an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery says about the appropriation of “cool.”

August 4, 2014

A purplish-blue neon lighted sign that looks more at home in the window of a blues bar than on the walls of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, spells out the title of the gallery’s current exhibit: American Cool. Just beyond the sign, visitors are confronted with one of the exhibit’s central questions: “What do we mean when we say someone is cool?”

It’s a question that has eluded teenagers and Hollywood producers alike through the years, but according to the exhibit’s introductory text, “to be cool means to exude the aura of something new and uncontainable.” The curators go further:

“Cool is the opposite of innocence or virtue. Someone cool has a charismatic edge and a dark side. Cool is an earned form of individuality. Each generation has certain individuals who bring innovation and style to a field of endeavor while projecting a certain charismatic self-possession. They are the figures selected for this exhibition: the successful rebels of American culture.”

The origin and concept of cool, the exhibit contends, is uniquely American—the term is credited to Lester Young, a 1940s African American jazz saxophonist who coined the term to refer in part to the unflappable attitude he and his fellow African American jazz musicians adopted in the face of Jim Crow-era racism and segregation in the U.S. Young also pioneered the use of the term to express appreciation and enjoyment for the work of other jazz musicians. Over the years, cool evolved into a term capturing an intangible quality, one that marries rebelliousness with a laid back self-confidence.

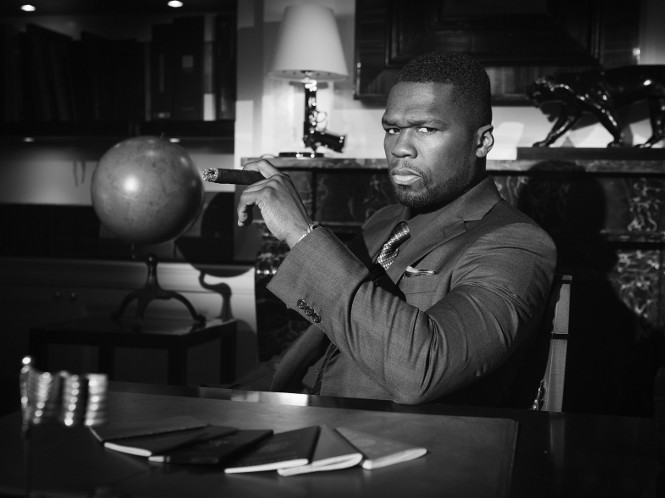

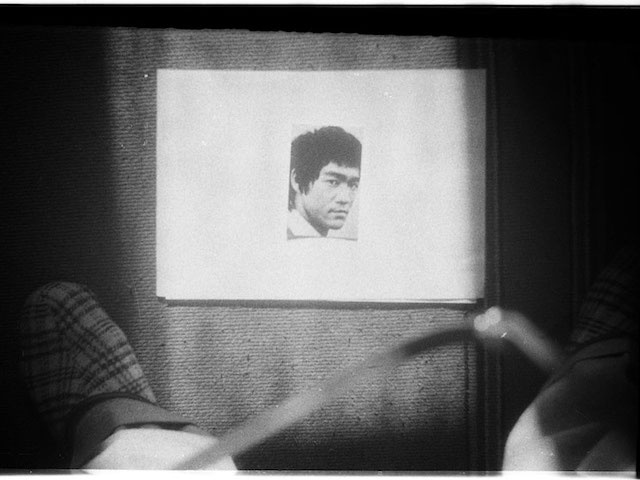

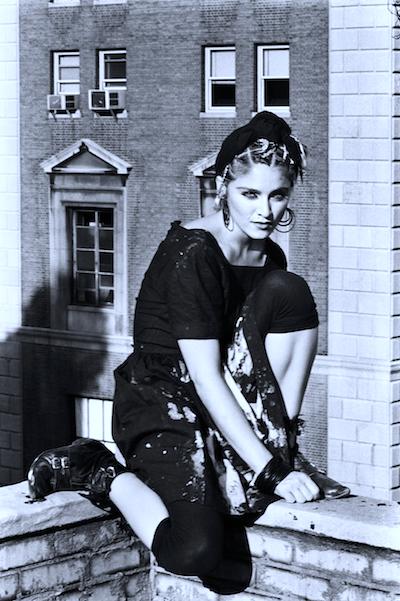

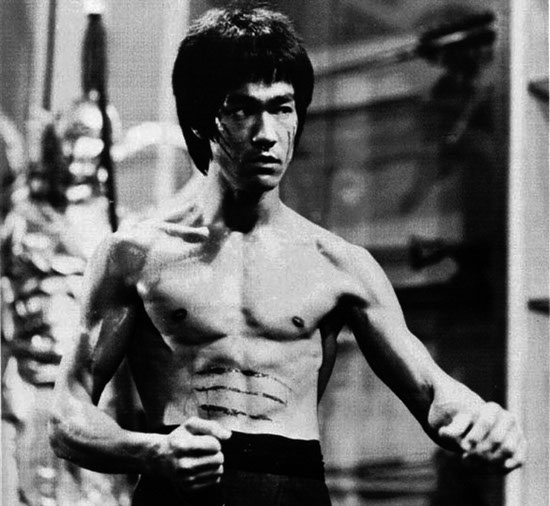

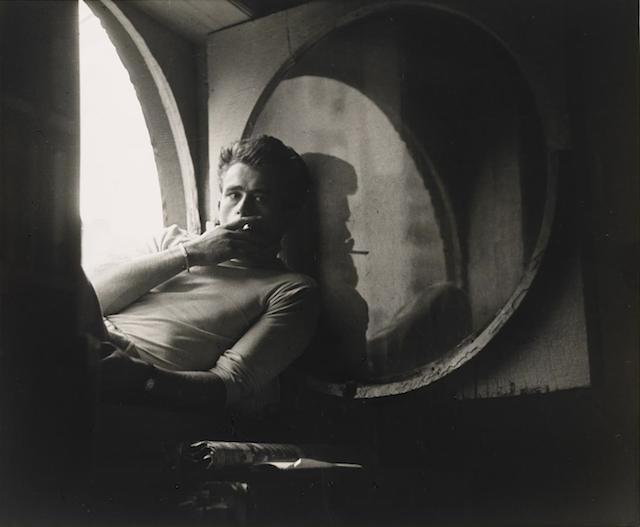

Combining photographic portraiture, history, and biography, the exhibition sets out to both define and document the embodiment of cool in the U.S. from the 1940s to present day. Photographic portraits of 100 individuals selected by curators line the walls of the gallery and are included in an accompanying catalogue bearing the same title. The portraits are stunning and artfully composed; most of them are black-and-white. And as we might expect, many of the featured individuals are instantly recognizable through these iconic images. There’s James Dean, Billie Holliday, Marilyn Monroe, Mohammed Ali, Clint Eastwood, Jimi Hendrix, Madonna, Jay Z, Johnny Cash, Bruce Lee, Patti Smith, Andy Warhol, John Travolta, Carlos Santana, and Miles Davis, just to name a few.

Some portraits truly capture their subjects at work, especially when it came to musicians. In photographer Roger Marshutz’s 1956 portrait of Elvis, the King of Rock and Roll oozes charm while performing live, tilting the mic and reaching for the outstretched hands of his adoring fans. In contrast, Lance Mercer’s 1993 portrait of a performing Neil Young depicts him head down, meditatively lost in the riffs of his guitar. Other portraits captured the essence of their very different subjects. Bombshell actress and personality Mae West sits ensconced in furs, cigarette lit, holding court with several men in tuxes whose faces are out of frame, while civil rights and prison abolition activist Angela Davis stands powerfully poised at a mic, likely at a political rally, mouth open and eyes blazing, radiating resistance against oppression.

But beyond the predictable figureheads of this exhibit, the curators provide the following explanation for how they chose all one hundred individuals whose photographic portraits are featured:

“Each cool figure was considered with the following historical rubric in mind and possesses at least three elements of this singular American self-concept:

1) an original artistic vision carried off with a signature style

2) cultural rebellion or transgression for a given generation

3) iconic power, or instant visual recognition

4) a recognized cultural legacy”

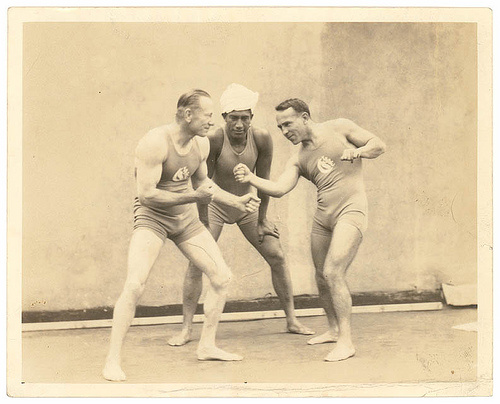

Alongside easily recognizable figures with iconic power were portraits of individuals I knew little about, such as jazz singer Anita O’Day, drummer Gene Krupa, jazz pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith, surfing pioneer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku, and boxer Jack Johnson. Short biographies accompany each portrait and provide an argument for why each of these cool cats embodies the concept of American Cool. It is through these biographies that I got to know new icons and discovered new aspects of familiar figures.

Given that the term cool was coined by African American artists and has deep significance to African American history and identity, it is not surprising that 30 African Americans are featured in the exhibit, ranging from Lester Young, who pioneered the term, to Miles Davis and Jay Z. African American writer and activist Rebecca Walker has thought a lot about the historical relationship of coolness to black culture, and the ways in which that relationship has been diminished. In her recently published edited volume of essays, Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness, she and 16 other writers try to answer the question, “What is Black Cool?” Walker writes: “If blackness is separated from this aesthetic of cool that comes out of our culture … we lose the understanding of how much we are actually giving to this world.” Similarly, in his New York Magazine article about the decoupling of cool from blackness, hip hop artist Questlove writes, “Black is the gold standard for cool, and you don’t need to look any further than the coolest thing of the last century, rock and roll, to see the ways in which white culture clearly sensed that the road to cool involved borrowing from black culture.”

Sure enough, of the remaining 70 portraits in the American Cool exhibit, 65 feature White Americans. But what is surprising is that only three portraits of Hispanic Americans and just two portraits of Asian Americans were included.

It gets worse. At the end of the exhibit, a wall of text acknowledges that it took considerable discussion and debate for the curators to whittle the exhibit down to just 100 individuals. Because so many did not make the cut, they offer an Alt-100 list of the next 100 whom, although they didn’t make it into the exhibit, they believe embody American Cool. There is no Asian American included in the Alt-100 List. Therefore, out of 200 individuals offered up by curators as embodiments of American Cool, only two Asian Americans fit the bill.

Those two are actor and martial arts icon Bruce Lee and surfing pioneer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku. Lee and Kahanamoku have certainly left an imprint on American culture, but the exclusion of other iconic Asian Americans who embody American Cool is problematic. It is precisely the decades depicted during this exhibit that saw a dramatic rise in the Asian American population, particularly during the past 50 years. And over that half-century, Asian Americans have contributed to the fabric of American cultural life.

So the question remains: how did Asian Americans end up largely excluded from a national exhibit about “American Cool”? Is there something inherent in the concept behind the exhibit or its definition of American Cool that left Asian Americans out? Or is the disconnect because of the application of these concepts to Asian Americans? Put in the bluntest of terms, are Asian Americans perceived as UnAmerican or UnCool, or both?

An important place to start is with the exhibit’s name and central concept: American Cool. We can break the concept down to its two parts (American and cool) and see how each relates to Asian Americans. While the curators of the exhibition provide their definition of cool and talk about it as a singularly American self-concept, they do not define American. American, according to the curators, it seems, is not only self-evident but also universally recognized and accepted.

But we need look no further than last year’s Miss America Pageant and this year’s National Spelling Bee to see that Asian Americans are not universally accepted as American even when they win quintessentially American competitions. When Nina Davuluri was crowned Miss America in 2014, becoming the first Indian American woman to earn the title, amidst the celebrations on social media were comments such as, “Miss New York is an Indian .. With all due respect, this is America.” Similarly, just a few months ago when the final four competitors of the Scripps National Spelling Bee ended up being Indian American, Twitter was lit up with comments like, “Okay, an American isn’t winning the spelling bee. 4 remaining.” Even more recently, Florida Republican congressman Curt Clawson mistook two officials from the Obama administration for representatives from India.

When we revisit the curator’s multi-pronged definition of American Cool, of particular significance is the definition’s last line, which describes individuals who embody American Cool as “the successful rebels of American culture.” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a rebel as “a person who does not obey rules or normal standards of behavior, dress, etc …” therefore, one can interpret the curator’s notion of “successful rebels” as those who not only flouted societal conventions and norms, but managed to make their own innovative vision, if not acceptable to all, then palatable to many. Meanwhile, Asian American communities have both benefited from and been hurt by the “model minority myth” and its very existence suggests that Asian Americans are viewed as predominantly “successful.” According to the mythology of this stereotype, Asian Americans have achieved success by playing by the rules, by working hard, and by integrating and assimilating into American culture, not by resisting and pushing the boundaries of those norms.

Not only has the stereotype been used as a weapon against other communities of color, but it also clearly ignores the diversity of Asian American experiences, whether related to differences in social class, language, generation, history, gender, sexual orientation, disability, religion, or immigration status. Historically Asian Americans have rebelled against both the traditionally held values of American society and Asian American communities. Among them are Asian American civil rights leaders Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs. The underrepresentation of Asian Americans in the American Cool exhibit likely has less to do with the lack of iconic and transgressive Asian Americans who embody American Cool and more to do with the fact that the exhibit’s definition of American Cool is at odds with pervasive stereotypes of Asian Americans. This underscores not only the persistence and impact of racial stereotypes but also the role that unconscious bias can play, even within cultural institutions.

Despite the fact that there are 18.2 million Asian Americans in the US (roughly 6% of the population) and that Asians now account for the fastest growing immigrant group in the country, they only account for 1% of this exhibit. But the question here is less about proportionate representation and much more about the importance of having Asian Americans and Asian American history regarded as American. The National Portrait Gallery plays a key role in creating and documenting a national narrative on American history, contemporary culture, and national identity. To feature Asian Americans in a meaningful way would not only acknowledge the essential role they have played in American history but would also confirm that Asian Americans and Asian American identity are woven into American national identity.

Not far from the National Portrait Gallery’s American Cool exhibit is the Beyond Bollywood exhibit at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, which examines the history and impact of Indians in America. This landmark exhibition is significant because it is the first on a national scale to focus on Indians in America. But as important as it is to have dedicated exhibitions exploring the specific histories of regional Asian American communities, it is just as important that these communities be substantively included in exhibits about national identity, such as American Cool.

Using photographic portraiture, history, and biography, the National Portrait Gallery’s American Cool exhibition is an attempt to nail down the singular concept of cool in the United States. However, the exhibit inadvertently demonstrates how ‘cool’ can end up a tool of exclusion. Created by African American artists as a transgressive stance against racism and segregation, it has now been widely appropriated and narrowly interpreted by mainstream American culture. The concept can now be used, then, to perpetuate the cultural marginalization of Asian Americans.

***

The end of the exhibit states, “American Cool is not the last word on cool but rather the first step toward a new national conversation on this singular American self-concept. Who’s on your Cool list? Here are two questions to consider: 1) Did this person bring something entirely new into American culture? 2) Will this person’s work or art stand the test of time and history?” So, given this invitation from the curators of American Cool, here are a just a few sorely missed Asian American icons of American Cool:

Ravi Shankar – The late, great sitarist Ravi Shankar is widely regarded as the leader of the movement that brought Indian music to America in the 1960s, and his influence was felt in American music and in world music, spurring George Harrison of The Beatles to dub Shankar “the Godfather of World Music.” Although now celebrated as the greatest Indian musician of modern times and as a pioneer, at the time, Shankar faced criticism from some of his fellow Indian musicians for his efforts to collaborate with Western musicians. Most egregious is the fact that the strains of Ravi Shankar’s sitar, which were heard at Woodstock and echoed throughout the American Counterculture movement, were left off the companion soundtrack to the American Cool exhibit.

George Takei – rose to fame for his role as Hikaru Sulu in the original beloved sci-fi television series Star Trek, making him one of the most visible Asian American actors of the twentieth century. But as a child, Takei and his family, along with thousands of other Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps. Takei has long used his platform as an actor to speak out about the treatment of Japanese Americans and Asian Americans and to advocate for LGBTQ rights.

Yuri Kochiyama – was a Japanese American activist and coalition-builder who fought for civil rights alongside African American activists. Kochiyama became a trusted friend of Malcolm X and was by his side when he was assassinated, a haunting moment captured in an iconic photograph. As a Japanese American who experienced internment, she actively advocated for reparations for her fellow Japanese Americans.

Maya Lin – In 1981 at the age of twenty-one, Maya Lin stunned the architecture and design world when her bold, modern design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was selected while she was still a Yale undergraduate. Her designs, though once regarded as controversial, have now become iconic of modern American public architecture.

Jhumpa Lahiri – Lahiri’s first collection of stories, Interpreter of Maladies, won a Pulitzer Prize in 2000. Her subsequent short story collection and novels have garnered numerous awards and prizes making them both critically acclaimed and popular worldwide. Beyond the literary accolades, Lahiri’s work serves as an important chronicle of the lives of Indian Americans.

Vera Wang – Wang has established herself as a leading designer of high-end and ready-to-wear fashion. Her elegant wedding dresses have become must-have items for fashionable American brides. But many don’t know that well before she entered the realm of design, Wang was a competitive figure skater and her start in fashion was not as a designer but as a fashion editor. After Wang was turned down for the top position at Vogue in favor of Anna Wintour, she reinvented herself as a designer.

Margaret Cho – Cho not only broke through the white male barrier of standup comedy in the early 1990s, she even managed to have a mainstream television sitcom focused on a Korean American family, All American Girl, which unfortunately was short-lived. She continues to be regarded as a bold and progressive voice in the comedy realm.

Mindy Kaling – Kaling rose to fame because of her role as Kelly Kapoor, on the hit television comedy, The Office and parlayed that into her own comedic television series, The Mindy Project. But before television, Kaling got her start writing and starring in theatrical comedies, including Matt and Ben, which was heralded at the New York Fringe Festival. As the star and producer of her own hit comedy television show, Kaling has not only become one of the most visible Asian Americans but has taken the baton passed by pioneering comedian Margaret Cho in creating a space for Asian American women in American situational comedies.

Vijay Iyer – Iyer is an acclaimed and accomplished jazz musician and composer, winning countless awards, most notably a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. In addition to being known for his musical virtuosity in a quintessentially American musical genre, Iyer is also known for his eclectic range, collaborating with musicians of varied backgrounds and genres, expanding the understanding of jazz. Beyond this, Iyer has also used jazz as a platform for dealing with social issues, participating in breakthrough collaborations with veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.