“There is something inherently powerful in adoptees speaking up and telling our own stories. And I will always believe that to be true.”

October 10, 2018

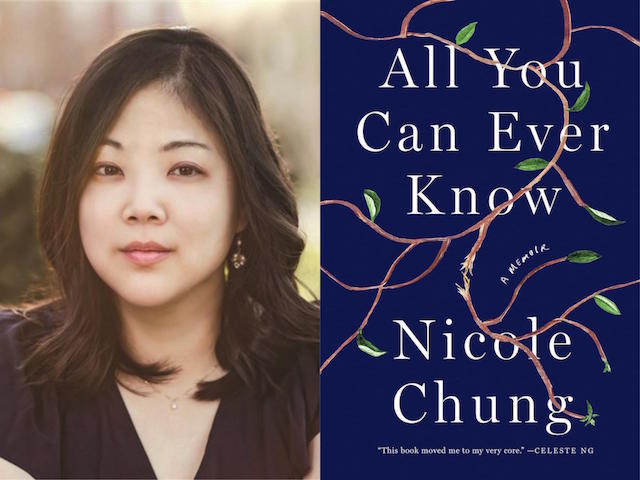

Adoptees are natural storytellers, Nicole Chung suggests, because we grow up telling our story repeatedly. Telling it, considering the gaps in it, knowing it by heart, even if at times, we wonder whether it is true. These questions compelled Chung, while pregnant with her first child, to embark on a search for her birth family. What she learned, the people she met, and the ways in which her life has changed since then are the subject of her moving, beautifully-wrought memoir, All You Can Ever Know.

Chung is the Editor-in-Chief of Catapult Magazine and the former managing editor of The Toast. Her essays and articles have appeared in The New York Times, GQ, Shondaland, ELLE, Longreads, BuzzFeed, Vulture, and Hazlitt. We spoke by phone earlier this summer. With warmth, candor, and thoughtfulness, Chung shared her insights about writing this book years after the events of the search for and reunion with her birth family, and about dealing with the grief of losing her adoptive father while in the final stages of editing the book.

With characteristic graciousness, she acknowledges the significance of speaking with a fellow Korean adoptee and about the importance of making space for multiple stories of adoption. “The dominant adoption narrative has been so shaped by people who are not us,” she says. “I don’t think there can be too many stories out there.”

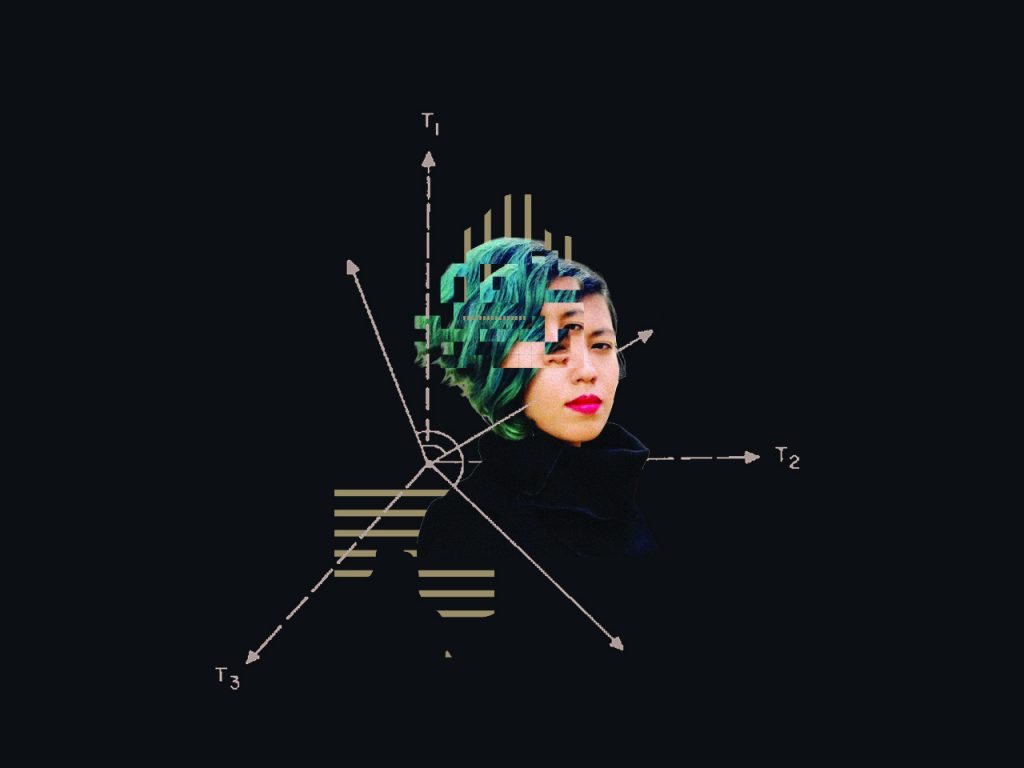

—Mary-Kim Arnold

Mary-Kim Arnold: You’ve published essays and also write fiction and short stories. I wondered if you ever wanted to fictionalize the story of your search for your birth family, or if you knew from the start it would be a memoir?

Nicole Chung: During college and before, I mostly wrote fiction and poetry. I never really expected to write nonfiction, but as an adoptee you end up talking about adoption pretty much all your life. I feel like many adoptees are natural storytellers and I think it’s because a lot of us grew up telling the story of our adoption over and over.

I grew up hearing this short, simple story and I really believed in it and internalized it. It took on this mythic quality: My loving, selfless birth parents were in a tough spot and gave me up because it was really the only choice they had. It was an act of love and self-sacrifice. I was born prematurely and had all these medical needs and spent months in the NICU. My parents didn’t want to give me up, but they felt it was the right thing to do.

It wasn’t until after my reunion that I started writing and pitching and publishing essays on my adoption. It wasn’t even immediately after, it was five or six years later. I was writing about the search while it was going on, but only in journals. I really wanted to have a record of what was happening to share with my children someday.

When I published my first essay I remember I was really surprised by the reaction, not just from adoptees—although certainly it was wonderful to hear from fellow adoptees that it had meant something to them—but also from people outside the adoption community. From people who had questions about it, or who had other experiences of being in these liminal spaces between countries or between cultures. Or from people who had experienced estrangements or knew of big secrets in their families. Reading my work was sometimes a way for them to think about these things.

I was surprised at how much those essays seemed to resonate with different people for different reasons. I kept getting a lot of questions, like the essays weren’t answering everybody’s questions; they were just creating new questions. I thought, well, if I had the length of a whole book to talk about this, I could try to answer all these questions. I could include the perspectives of all of the family members.

As for why it was nonfiction and not fiction… I figured that even if I wrote a short story or a novel informed by my own experiences, most people would assume it was autobiographical anyway. So I figured I might as well try to own the truth and say what really happened. I also felt there could be additional power in writing that truth as an adopted person, because our stories are so often told for us. There is something inherently powerful in adoptees speaking up and telling our own stories. I will always believe that to be true.

Toward the end of the book, you share this observation that there is no closure in adoption, it’s this ongoing thing. As writers, we have to put some sort of shape on the mess and the exploration. I wonder how you were thinking about the form the book might take, and how you were thinking about where to end it.

At first I imagined telling the story purely chronologically, but then as I started writing, I felt like it took too long to get to the search. This book was really about my search and my birth family and trying to find the answers to questions I had always had. For the first half or so, I ended up toggling back and forth between my childhood growing up adopted in a white family, and the events that led to the decision to the search.

Once I make the decision to search, the story is more chronological. The end was tricky because it’s not as though anything is ever really truly over, it’s an ongoing story—for me, for my birth family, for my adoptive family, for my children. I had to stop thinking about endings and think instead of the point at which I found some kind of an answer. Not the answer, necessarily—maybe just the point at which I found a new question to ask about who I was, now that I knew more about my history.

That’s an interesting way to put it. The point at which one question was answered or a new question arises. Do you have a sense of what that next question is?

A lot of my questions now relate to my children, and my niece—the next generation. It’s not as though adoption is just this one event that happens at a fixed point in time. I knew that was true in my own life, but until I became a parent and my kids began asking questions about it, I hadn’t thought as much about the impact on the next generation.

There’s a lot of trauma in our family history, and as my children learn about that, I wonder what they will think and how will they feel about it. It’s something over which I won’t have control, and I don’t want to have control over it: It’s their right to feel how they feel. But I hope that I am up to the task of talking with them about it and trying to help them figure out how to make a place for it in their own history, as part of their identities.

You mentioned your niece and that there are these reverberations through multiple families over multiple generations. That’s not something that we talk a lot about in adoption, which I guess is related to another question that I had around your birth sister, Cindy. You do this really beautiful thing early on—you linger in Cindy’s story, offer her this space. I’m curious when you knew that Cindy’s story would be so important here, too.

I always knew that she would be a big part of it. It was such a great revelation when I found out about her. I wanted that moment to feel like the huge event it was, and it’s hard to do if we don’t know who she is before that.

She was told one thing about what happened when I was born, when she was six, and then didn’t learn the truth for many years. I didn’t have anything close to the full truth, but I had so much more than she had.

I found I really loved writing from her perspective. She was a conduit to this history that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. You know, when two people grow up hearing separate stories, and you put them together to see how they fit like jigsaw pieces and how the stories get bigger—I really wanted that to happen in the narrative, and there’s no way to do that without giving my sister room in this story. In a way, she had the upbringing I could have had. We started out on this parallel track together, and it’s interesting to me, still, to think about what could have happened if we had stayed together. I think that’s a natural question as you read; also in my life, generally—what if I hadn’t been adopted? Cindy is one of my “what could have been”s.

Nobody chooses their parents, of course, but adoption can really foreground a sense of randomness. When I was adopted, I traveled from Korea with a group of children and babies, and years later, had the opportunity to see glimpses of other children, their parents, their lives. Random is the only word I can think of: Why this family and not that one, why her and not me?

Absolutely. I think about that all the time. Growing up, I would think, What if I had been adopted by that family? or What if I had been adopted by famous people? All the different scenarios I could have ended up in, but didn’t. Not even because I wished for something vastly different—although, sure, sometimes I did.

I think the randomness of adoption can feel a little scary. I think that’s partly why so many people use this language of “it was meant to be,” and they talk about fate, and they talk about God. My family did this and I completely understand that urge, because the randomness can seem so frightening. It’s appealing to believe that there’s some sort of divine plan, or there’s fate at work. That’s certainly what I was told to think about my adoption when I was a child, and what I thought for a long time. I think I found comfort in that idea.

There’s some sense, there’s some meaning.

Right. It means something, it was supposed to be this way.

You make a comment about adoptee stories and what a defiant and hopeful act it is to try to claim one’s self through stories. I’m thinking about the activeness of that idea of re-claiming in parallel with the idea of permission. My adoptive mother passed away when I was in my early twenties, so by the time I wrote about my adoption she had been gone for many years, so there wasn’t this sense that I felt I needed any permission, or that I was betraying anyone. Your family is so present all the while you’re trying to make sense of this exploration. Did you ever feel like you needed permission?

Did I feel like I had permission [to write the book], or did I feel like I had permission to search in the first place?

Both. I mean, the writing of it puts it out in the public in a way that the search might not have to.

In my adoptive family, we had talked about the idea of a search and reunion for years, and in the book I say it was like talking about becoming an Olympic athlete—those two things seemed about as equally likely to me when I was a kid. They would say things like, “When you’re older, when you’re ready, if you choose to, you can search.” I knew they didn’t really want me to. I always felt hesitant about it, unsure of how to do it, and I didn’t really know how I would have that conversation with my adoptive parents if and when the time came. In the end, it was made easier for me by the fact that I was pregnant with their first grandchild. I had this built-in reason for searching. I told them I think it would be really important to get medical history and information. And I did say I was curious about [my birth parents]. I could tell they were a little bit uncomfortable and surprised, because I was pregnant. My mother was like, “Well, don’t you have enough to do right now?” It’s true, I really did.

It really is a good question!

Even good friends of mine who were very supportive were like, “Wow, you do have a lot going on, emotionally. Is this really the time?” I completely understood—there were so many reasons not to search when I did. But the strongest reason to do it was the pregnancy, the fact that I was becoming a mother and thinking so much more than I ever had about what that meant, what kind of mother I would be. I was trying to understand my own story and what I would tell my child, and I wasn’t satisfied with the fact that I had so few answers for them. I had researched the process before, I had even talked to some intermediaries, but the pregnancy is what finally pushed me to act.

I only started writing about it many years after the search and reunion. My adoptive parents and I had talked about it a lot and they had already had a chance to see how it worked out, how my search didn’t mean that I wasn’t their daughter and it didn’t mean that I didn’t love them. It didn’t mean that I thought my birth family was more important than our family.

My mother used to joke, “Well, just don’t write anything mean about us.” I don’t think I wrote anything mean about them! But I thought about that often when I was writing. I was pretty nervous to show it to them, but I showed it to them early on and waited really anxiously for them to say something. I wasn’t expecting it to go badly, necessarily, but of course I was still anxious. Their responses were very generous and loving. They didn’t ask me to take anything out; they didn’t ask me to put anything in. They didn’t question my memory, or say “that didn’t happen that way” or “how could you write this about us?” They actually really loved the chapter that was about them specifically—the early chapter about how they got married and moved out West, and how they came to adopt me. My mother said, “It reads like a novel, you know, but it’s the truth.”

That’s great to hear.

Yeah, it’s a complex story. I didn’t feel like I was pulling my punches ever. It was a different era, too, which I think is important for people to understand when they read about my adoption. We talked even less about race and culture in adoption than we do today.

I think at one point toward the end you’re talking about taking Korean lessons and teaching your daughter. You expressed your concern about whether this might be a kind of “glorified cultural appropriation.” I’m curious about how you feel your relationship is to Korean-ness now.

That’s such a fraught question. I wish I had a good answer! I don’t think that I’ll ever feel truly Korean. I wish, so badly, that I did.

I’m deeply proud of my heritage now, and at the same time, because of the way I was brought up, I’m so Americanized and there’s no going back, you know? I would have been, somewhat, even if I had been raised in my birth family. My birth parents were immigrants, so I still would have been raised in this country, with everything that means and all of the pressure to assimilate.

I think I’ll always feel as though I exist between two cultures, though of course I am not alone in that. Most of the time I think about myself as Korean American—one full but complicated identity.

You mentioned the essay you wrote for Longreads. I was so sorry to read that your dad passed away.

Thank you.

I was thinking of course not only of that grieving, but also how that really casts this shadow over what you’ve created and adds this new layer to the story that you were trying to tell.

The hardest parts of the book to read now are the parts with my father. I found out about his death in January, and the day after, my final draft of the manuscript was due. I’m sure I could have gotten an extension, but I pushed through because I was in shock; it wasn’t really hitting me yet. I figured it would eventually hit and I’d be a mess. So I thought, I’ll do this now because in a couple days I might not be functional.

It’s been so hard. I’d be lying if I said publication were this purely joyful experience. Of course, is it for anybody? It’s really hard to write a book and have it out in the world. I did feel like I’ve had a particularly hard time having to edit, finish, promote, and talk about the story—this really intimate family story—when a part of my family is gone. I’m grateful, too, so grateful, but this will always be the year my father died, first and foremost, even if it is also the year my book went out into the world.

Some days I’m very depressed; in some ways it’s harder now than it was in the weeks right after his death, because right after it happens, there’s so much to do and focus on—everything from the memorial to making sure my mom was okay, and traveling out for the funeral. Now, with each passing month, every milestone, it sinks in anew that he’s not coming back. I can’t pick up the phone and talk to him, ever, and he won’t see this book in the world. He never read the final version. He won’t see it as a finished book and he won’t get to experience that feeling of pride.

I know he liked it, and I’m very thankful for that. He was especially happy that one of his goofy jokes stayed in the book. I’m really happy he got to read part of it before he died. But he didn’t actually get to finish it—he died in the middle of reading it. That will always haunt me, I think.

The book itself is so personal and represents such a journey. Even though it was long after the search and the events that you’re talking about, I think the act of finishing something so intense and complicated is so emotional.

Sometimes I feel like my dad’s death has really hit me and I’m dealing with it, and other times I feel like I’m managing or scheduling my grief, which is a terrible feeling. For weeks now, I’ve been breaking down and crying on Friday nights, after the work week is over and I don’t have any more editorial obligations and my kids are in bed. It doesn’t feel good to realize I’ve been compartmentalizing my own grief, but there’s so much to do—especially for the book—and I can’t really afford to break down every day, or every time I feel like it. Part of me wonders if I’m delaying it, or extending it in some way.

In any other year, this book would be the biggest and most important thing that happened to me, but because it’s happening this year, it’s not. I’m wrestling with what that means, too.

I know this is a terrible question to ask a writer, but are you working on another book now?

[Laughs] I have started a novel. I don’t want to talk about it yet as I’m still deeply insecure about it and don’t want to jinx the whole thing, but yes.

One thing I really hope to do someday is to edit an anthology of other adoptees’ writing. I’ve been so glad and honored to edit and publish fellow adopted writers in Catapult. One thing I really want this book to do—and one reason I’m so grateful that you’re writing, and that your book is out, too—is to open the door for more adoptee stories and perspectives. The narrative around adoption has been shaped by people who are not us. I don’t think there can be too many adoptee stories out there. I’d love to see more books. Many more books. And if I can help make that happen, I would love to.