Author, professor, and provocateur Amitava Kumar has a very specific question for New York City book clerks.

June 4, 2012

It would be performance art—a bit like doing brownface, except not. The idea thrilled him as soon as it was proposed by his editors. He was to go to a few bookstores in New York City and ask: “Where is your ‘White literature’ section?”

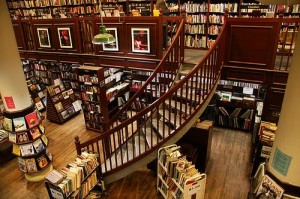

He began with McNally Jackson Bookstore on Prince Street.

In the display window he saw some of his friends’ books; there was a reading that evening by his pal who had written about an Indian-American man who lived out in the desert with his angry wife and autistic son. Inside there was a café. At one table, two women were talking in German. He returned to the front desk, but there were several people there and he felt intimidated. Coming back to the café section, he asked for a Moroccan mint tea.

The windows had been thrown open. It was a lovely spring morning. The girl in the shop opposite had come out onto the street and was photographing her displays—three large teddy bears in short dresses. A young man sat down next to him with his cappuccino and a black, bound copy of Bolaño’s Antwerp. The man went back to the front desk.

“Where is your ‘White literature’ section?”

The salesclerk, with his muscular body encased in a bright red t-shirt, could have been just as at home behind the counter at a bicycle store. Let’s say his name was Josh. Hearing the question, Josh stopped for a second, but without betraying his amiable self. He said reasonably, “That would be the literature of white countries…”

Extending one finger of his right hand, and then another, he counted, “England, France…” And then said, “Let’s walk over there.”

En route to the shelf, Josh said with a smile, “The majority of literature is white.” He was pointing at rows of books in front of them. The first one he picked out was Nicholson Baker’s House of Holes. “He’s fun,” he said. To Baker’s right there was Don DeLillo. He got a mention as well.

Josh said, half to himself, “Who are the great white authors?” Immediately to his right was the seeming answer. Withdrawing a copy of Freedom half an inch from its place on the shelf, he gently intoned, “Franzen.”

Josh mentioned Hemingway and immediately discounted the recommendation by explaining kindly that Hemingway wasn’t contemporary. He waved an arm at a line of Cormac McCarthy paperbacks but proclaimed them too bloody. Walking over to a bank of Philip Roth books, Josh said, “He was born in New Jersey, he is Jewish. His name is Philip Roth. He is amazing.” Putting a reverent hand on American Pastoral, he continued, “This is incredible.”

The grateful customer acknowledged that he had perhaps heard of Roth. He took down the book he had been shown and sat down on a chair to read from its dust jacket. Josh, his sweet-natured guide, looked down at him, still full of amiability, and said as he left, “Enjoy, buddy.”

The man had actually read Roth’s American Pastoral some years ago with great attention. There was a quote from that novel carefully copied down in his writing journal at home: “The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.” Some other images from the book had also stayed imprinted in the man’s mind—the strength and confusion of Swede Levov; rich, detailed descriptions of glove-making; more disturbing, the Swede’s daughter, Merry, who became an arsonist and then a Jain—and now he returned to them in his quiet corner.

But only for a minute, because the emotion he experienced more strongly was guilt. He hadn’t lied, not exactly, but he had engaged in subterfuge. Why hadn’t he practiced straight journalism? Why hadn’t he come into the store, produced a business card, taken out a pad and asked blunt questions like, “Who decides on these categories? Can you tell me if there is any debate between you guys?” He hadn’t done that and now he would never be allowed to appear on This American Life! The man saw his dreams drown in this sea of guilt. Imagining a rescue, or at least an escape, he chose Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, and having paid $15.75, quickly left for another bookstore.

He wanted to get this over with. Close by was Housing Works bookstore on Crosby Street. He waited in front of the sign that said “Information.” Above him were signs marking other sections: “Health,” “Diet and Fitness,” “Lesbian and Gay,” “Sexuality.” He asked his question. Again that momentary look of blankness: the confusion of categories. The person helping him was a short, pudgy Asian man. “White literature?” he repeated, skeptically but not unkindly. Near them was a cart loaded with books. The Asian man walked over to the cart and said, “It’s all mixed…” With his finger on Chekhov’s The Shooting Party, the sales-clerk informed him, “He’s Russian.” The man looked at the price on the book. Five dollars. That was tempting. He noticed that the sheet of paper stuck to the cart’s side said, “‘Literary Classics’ (Read the books you say you’ve already read).” On another cart nearby were cheaper books. Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow was available for only one dollar, but he had decided that he’d only buy books by white people that day. He put down three dollars for Henry James’s Washington Square.

The man walked to Astor Place. He had been to a branch of Barnes & Noble there some years earlier, pushing his daughter’s stroller inside and buying her chocolate milk. But he couldn’t find the store now. What to do? On his list was St Mark’s Bookshop, located only a few blocks away. Cool, nicely-lit interior, elegant rows of books on critical theory. With some trepidation, the man approached the sales counter. The woman wearing large glasses and large hoop earrings was barely unable to conceal her contempt. “What do you mean? Literature that white people write?”