A Filipina nurse’s family life during the pandemic in New York City

May 17, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following reported feature by Vina Orden is part of a notebook of writing on the theme Nurse. Read other pieces in the collection gathered here.

On March 28, 2020, just a little over a week after New York ordered public schools, bars, and restaurants closed and non-essential workers to stay home in an effort to limit the spread of Covid-19 across the state, Noemi* noticed that her body felt achier and warmer than usual. She was scheduled to work that evening, so she took a couple of Tylenol pills and didn’t think too much of it.

It was the same the next day, except by the time work was done, she felt extremely exhausted. Noemi suspected she had Covid-19 after being exposed to the virus a few weeks before. With a diabetic husband and two sons living with her in a two-bedroom apartment in New York City, she decided to sequester herself, just in case.

She and her husband Bong built a makeshift “isolation room” for her in their foyer, made of two bookshelves draped with thick, clear plastic shower curtains, taped shut to contain the air. It was equipped with hand sanitizer, Clorox spray, an extension cord, and a small foldable mattress where she slept. “When I woke up, I felt like a ton of bricks were holding me down. I didn’t lose my sense of taste, but it was distorted—metallic and bitter.” She was certain then that it was Covid.

The next day, Bong came down with a fever too. She worried that with his chronic disease, he would be vulnerable to the worst of the illness. The number of new cases in New York City had crested to 6,130 on March 30. Noemi, who is a nurse in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at a hospital in Manhattan, already had seen many patients hospitalized for Covid, dying after days of agonizing symptoms without family members beside them.

Bong’s symptoms turned out far more severe than hers. He ran a fever 10 days in a row and experienced shortness of breath. Noemi also noticed rales in his lungs when she examined him with a stethoscope. This meant there was fluid in his air sacs, which was usually a sign of pneumonia. They tried scheduling a Zoom appointment with Bong’s doctor but couldn’t secure one until the sixth day of his illness.

When they finally spoke with the doctor, she merely recommended rest, fluids, and Tylenol—Noemi had to push her for antibiotics to treat Bong’s pneumonia. I asked why she had assumed her husband’s care at home, especially when she herself was ill. Noemi replied, “I tried my very best to avoid hospitalization because I knew fully well that I might not see him for a while or, God forbid, ever again.”

□ □ □ □ □

The Covid-19 pandemic wasn’t Noemi’s first tour of duty on the frontlines of a public health crisis in New York City. She immigrated to the U.S. from Manila, Philippines in March 1988—right in the midst of the AIDS epidemic. She didn’t always want to be a nurse, but like many other Filipinas, it was among her viable career options. She was surrounded by aunts who were nurses and happened to attend a high school with a pre-college program that would allow her to waive the entrance exam to nursing school. After graduation, she worked for a year in a hospital in Manila before getting recruited at the height of a nursing shortage in the U.S.

“I didn’t even plan it. I just accompanied friends for an interview and inadvertently got recruited as well,” Noemi said. “My mom was sick with cancer at that time. The thought of being able to afford the medical expenses needed to prolong her life or by some miracle, to give her a chance for a cure, were reasons enough to move ahead. It was also what she wanted.”

Noemi joined the ranks of the more than 20,000 nurses who leave the Philippines each year for better-paying jobs and a chance to build careers and lives in other countries that offered the promise, if not avenues, for socioeconomic mobility. Eight months after immigrating to New York, Noemi’s mother passed away. Noemi grieved by herself a continent away but despite the loneliness, stayed on in the U.S. to support her brother in the Philippines.

Owing to policies of both the governments of the Philippines and the U.S. around the grooming and export of medical labor (which can be traced back to U.S. colonization from 1898–1946), over 150,000 nurses have left the Philippines to permanently settle in the U.S. Today, many Filipino and other foreign-born nurses are assigned acute care or critical care roles, making them among the most vulnerable healthcare workers in this pandemic. According to National Nurses United, the largest nurses’ union in the country, while 4 percent of nurses in the U.S. are Filipinos, 31.5 percent of Covid deaths among registered nurses in 2020 have been of Filipinos.

Noemi spoke about how working on the frontlines of the AIDS epidemic helped prepare her for the current crisis. Back then, she had been assigned to a ward of mostly homeless men with alcohol and drug addictions, some of whom were HIV-positive but didn’t have full-blown AIDS. “Being in that setting taught me how to be tough,” she said. And—echoing the xenophobia many Asian American healthcare workers faced at the outset of the Covid pandemic when President Trump kept using the racial slurs “Chinese Virus” or “Kung Flu”—Noemi recalled that a number of her patients then were “big, burly muscular men who cursed you at the top of their voices, telling you to go back where you came from or belittling you with vulgarities when they didn’t get what they wanted. I learned how to take it all in stride and stood my ground.”

Then, as now, she was met with some “difficult” patients—non-compliant, manipulative, even sexist and racist. But as a nursing professional, she has had to rise above those personal attacks to advocate for her patients and get them the proper care they needed. “As a nurse, you do not compromise lives. You learn to see past those difficulties and treat each one of your patients as a person in need. I became a nurse because it gives me emotional and spiritual satisfaction knowing that, in some small way, I helped reassure a friend, comforted a family, or even saved a life,” Noemi said.

During the Covid pandemic in particular, many patients endured the suffering on their own and passed away without family and loved ones around them. “In those instances, we nurses became their ‘family’—for as poor substitutes as we were. We held their hands and prayed with them ’til their last breath. We also felt their family’s helplessness, and all we could do was cry with them.”

While she may have had a blueprint for dealing with Covid at work, nothing prepared her for having to manage work (let alone as a healthcare professional) and family life in the pandemic.

□ □ □ □ □

Noemi and Bong’s families hailed from the same provincial town in the Philippines. They came to know each other over time, as Noemi returned annually from Manila for vacations. But she didn’t seriously entertain his courtship until she already had decided to leave for the U.S. A year later, they had a civil wedding, and Bong eventually joined Noemi in New York. They were newly married in their mid-30s and decided to start a family right away.

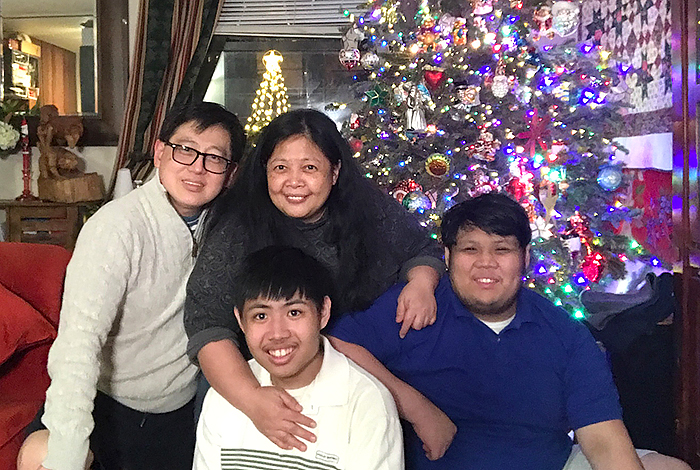

At the beginning of the pandemic, their eldest son Isaac was a graduating senior at Brooklyn Technical High School and their youngest, 14-year-old Noah, was a special needs student at his neighborhood public school.

Adjusting to life in the pandemic was especially challenging for Noah, who is on the autism spectrum and thrives on routines. He is classified as nonverbal, but his family still talks to him normally, though repetitively with cues. Once in a while, Noah responds immediately with the appropriate answer, so his family knows that he can understand them. Noemi recalled how confusing it was for him to develop new routines, such as wearing a mask, washing and sanitizing his hands frequently, eating meals in the bedroom he shared with his brother, and having to distance himself from his Mama and Papa during the course of their illness—especially once they moved to a separate apartment.

The hospital where Noemi worked had accommodations for doctors and nurses who wished to isolate, as well as out-of-state healthcare workers who came to help at the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in New York City last spring. The hospital granted Noemi and Bong a week’s stay in one of the apartments while they recuperated. But it meant having to find a way to take care of their sons, who were staying in a separate apartment on the same floor. “There was no night or day for Bong and me—we just tried our best to function when we could, until fevers or shortness of breath sidelined us back to bed or to the sofa.”

Noemi would don full personal protective equipment (PPE) to prepare the family’s meals. She would text her sons once the food was ready, asking them to go into their room and shut the door behind them. She and Bong took turns delivering the food, which was fully wrapped, and only after sanitizing the kitchen with alcohol and bleach and leaving the boys’ apartment would she text them to come out and eat. Once they were done eating, the boys would leave the dishes outside their door and text their parents to pick them up.

In April, the family celebrated Isaac’s and Noah’s birthdays, with the brothers on one side of an ironing board that propped up a cake and their parents eight feet across from them on the other side. Needless to say, these were memorable occasions, though not for the reasons anyone would wish. The family had no physical contact with each other that time they were apart and took solace in humorous video calls and texts.

□ □ □ □ □

New York City public schools had shut down on March 16; by the 20th, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive order “New York State On Pause” had taken effect and all non-essential businesses closed statewide. Both Isaac and Noah had to take their classes remotely. For Isaac, who was in his last year at Brooklyn Tech, adjusting to online learning and keeping up with his lessons was relatively easy. However, doing his own work while also being thrust into the responsibility of caring for his younger brother day to day was a challenge.

In addition to helping his brother with schoolwork, he also had to make sure Noah finished his meals and brushed his teeth afterwards. In the evenings, Isaac would stay up until he was sure Noah had fallen asleep—although, one time his brother “escaped” at 2:00 in the morning to their parents’ apartment.

Isaac was somewhat disappointed that he and his classmates were unable to partake in traditional senior rites, such as the trips, prom, and graduation. He, like so many other students around the country, participated in an online graduation ceremony last year. The day after the ceremony, Noemi took him to Lincoln Center and Times Square to take photos of him in full graduation regalia. Strangers clapped and congratulated him, and even NYPD officers greeted him with their megaphones.

Noemi shared her concerns as a parent in this pandemic, which posed different sets of challenges for each of her sons. Last September, Isaac began his freshman year at the University of Rochester. So many questions ran through her mind as they dropped him off at school and waved goodbye. She was afraid of him contracting Covid, but also about the other things parents usually worry about as their children slowly untether themselves and learn how to be independent. Is he mature enough to be on his own? Is he capable of making sound decisions? Will he be bullied for his hearing loss and for using hearing aids, or for something else? Does he know how to do his own laundry?

Despite a rough start, Isaac managed to survive his first semester—mostly holed up in the dorm taking classes remotely and only going outdoors for essentials. Noemi is relieved that he’s getting along very well with his roommate and also has made other friends.

She has been concerned and frustrated about Noah falling behind in school. For the first few months of the new school year, both working parents struggled to supervise him while he was taking classes remotely. Whenever he could, Bong helped Noah—who is very good in reading, spelling, and mixing music—with reading and workbook activities. But Noah missed a class now and then when Noemi came home late from her night shift, or when she needed to avoid close contact with him as a precaution after having cared for a Covid patient the night before.

Now, Noah is back onsite for school, but because he has heightened sensations around his mouth and nose, keeping a mask on properly for a whole day has been a huge challenge for him. Noemi constantly worries about him catching the virus. His school has shut down thrice since reopening because of contamination, and Noah had been on a contact tracing list (so far, he’s tested negative for Covid). But she is most anxious about his education, “I feel I have neglected him, despite trying my best. The inconsistencies—switching from remote to in-person classes, then back to remote—and his missing some schooldays have been a huge setback.”

□ □ □ □ □

The pandemic has extracted a toll on many New York City families, but it has placed an extraordinary burden on parents and caregivers of the approximately 228,000 children with disabilities who rely on the public school system for individualized education programs (IEPs) and the in-person support of trained professionals like counselors and special education teachers. Many of these services have actually been reduced during the pandemic, and it has left working parents like Noemi overwhelmed with the impossible task of acting as their children’s teacher and therapist as well. For Noemi, there’s an added emotional burden knowing that despite her best efforts, Noah will likely regress without the consistency, structure, and socialization vital to his learning.

With his new and inconsistent routines during the pandemic, Noah has been exhibiting signs of emotional dysregulation as well. “Sirens (which we hear all the time these days) or even a ringing phone can mean the difference between a good day and a bad day,” Noemi related. “I’ve learned to stake out places for potential untoward stimuli and try to avoid or work around them. But on a bad day, it means full-blown tantrums and meltdowns, no matter where we are. I’ve learned to ignore other people’s stares and just focus on settling Noah down and redirecting him.”

Through it all, Noemi has been grateful. To Isaac, for being a loving, empathetic brother who helps ensure Noah has more good days than bad. To fellow healthcare workers who took time out of their own busy lives to check in on the family and drop off needed sustenance and other thoughtful extras. Noemi also has learned a few lessons in this difficult time. Life has been unpredictable for her family, but she believes that for so long as they have faith in their hearts, they’ll be able to get through the constant changes together

I asked if there was anything in particular that she wanted readers of her story to come away with. Noemi replied, “Life is precious. Let us help each other out. A little act of goodness, kindness, and respect, in the light of the current situation, makes a lot of difference. And always have a prayer to fall back on.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Gloria C. Orden worked as a nurse in the U.S. for three decades until her retirement in 2017. She is now fully devoted to her art.

The passing away of two of her coworkers and a front-page obituary in The New York Times on May 24, 2020 initiated her collage series, “Elegy to the Immigrant Health Worker,” including this one titled, “#11 Another Pandemic, Another Nursing Shortage.” All of her Covid-19 related works are a tribute to her former co-workers and friends, many of whom are immigrant health care workers who contracted Covid-19, some of whom died taking care of Americans in this pandemic.

*Noemi’s last name has been withheld for privacy.