Filipino American activists in New York resist invisibility and displacement

November 27, 2020

This October, communities around the country observed Filipino American History Month (FAHM). It was an opportunity to reflect on what it means to purposefully celebrate history rather than heritage as well as on this year’s theme, “The History of Filipino American Activism.” What is significant about the focus on history isn’t so much locating when and where Filipinos first set foot on Turtle Island (or what is now called the continental United States) – which can be just as dangerous as any other settler mythology that erases indigenous history – but rather, the provocative idea of resisting invisibility in the master narrative of this country and empowering Filipino Americans to document our own stories.

In mid-October, the Filipino American National Historical Society-Metro New York Chapter (FANHS-MNY) hosted the panel, “Stories of Fil-Am Activism in Gotham.” It brought together intergenerational Fil-Am activists engaged in various forms of resistance around different (but often intersectional) issues. While the work of Filipino activists in New York City hasn’t been as consistently documented as the stories of those on the West Coast, it is apparent that we have as rich a history of fighting for dignity and justice for our community; of affirming that we belong here, not just because of our labor and economic value, but also for our contributions to the culture and social fabric of our city and this country.

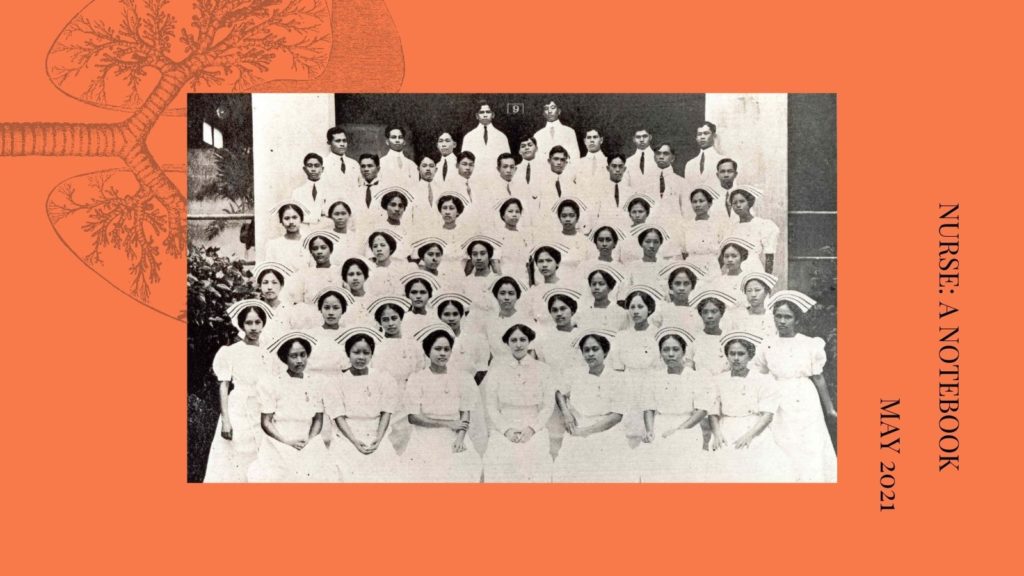

Of course, New York has the distinction of hosting Philippine national hero Jose Rizal in 1888, but like him, many of the Filipinos who arrived here in the first half of the 20th century – as U.S. nationals serving in the U.S. Navy or the Army, as pensionados (sponsored by the U.S. government to study at institutions like Columbia University and New York University), or as entertainers – ultimately returned to the Philippines. Most Filipinos who settled in New York, including many nurses and their families, were part of a wave of immigration that followed the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Still, compared to California, which has a Filipino population nearly 12 times greater than New York, one might wonder where the Filipino community and the activists are in the city.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest American Community Survey data (2018), an estimated 86,000 Filipinos live in New York City, about 54 percent of them in the borough of Queens. Around 13,000 Filipinos live in the neighborhood of Woodside, dubbed “Little Manila Queens,” making up 15 percent of all residents in the area.

Walking along Roosevelt Avenue, Woodside’s main thoroughfare bisected by the elevated 7-line subway tracks, one can see the imprint and impact of Filipinos on the neighborhood – from the iconic Phil-Am Food Mart, which stocks Filipino/Asian produce and staples like pan de sal rolls; to bakeries, restaurants, and even the Filipino fast food chain Jollibee; to money transfer services and a branch of the Philippine National Bank; to balikbayan box shippers; to the Roman Catholic Church St. Sebastian, which offers a monthly Tagalog-language mass. It is harrowing to think that the neighborhood could have been lost to real estate developers four years ago.

FANHS-MNY panelist Steven Raga – chief of staff at the New York State Assembly, board member of Queens Community Board 2, and a New York State Advisory Committee member for the U.S. Federal Commission on Civil Rights – brandished a red placard with the words “No Megachurch in Little Manila” on his computer screen. Raga recalled how, in 2016, a coalition of organizations – including Anakbayan-New York, BAYAN-USA, the Filipino American Democratic Club of New York, The Filipino School of New York & New Jersey, Migrante-New York, National Federation of Filipino American Associations (NaFFAA)-New York, New York City Asian-American Democratic Club, New York Committee for Human Rights in the Philippines, Philippine Forum, Queens Anti-Gentrification Project, Ugnayan, and UniPro (Pilipino American Unity for Progress, Inc.) – helped mobilize Filipinos and other Woodside residents around the “Defend Little Manila” campaign.

Together, they successfully beat back a plan by megachurch developers who, without community consultation, had requested special permission from the city government to waive building-height restrictions to construct private apartments for church leaders, a spa, as well as an 11-foot wall around the complex, shutting it off from the street and threatening the businesses and the lively street life that characterized it. Local parking options would have been drastically limited during the proposed construction period and would have had an adverse impact on dine-in customers at the many restaurants and shops in the area.

Seeing how gentrification has effaced the character of other neighborhoods in the city, members of the Woodside community also worried about the impact of such large-scale development on property values and the potential displacement of working and middle-class residents due to rising rents and the cost of living.

Raga spoke of the importance of civic participation at the local level: “When you live in highly populated Filipino neighborhoods like a Woodside, or a Jamaica, Hollis, in Brooklyn, and the city, we have to have our community known to the local entities, and elected officials, and the agencies, or they’re just gonna think that we’re not there, or we’re not involved … It was a real victory for the community and our allies back then. It was a real, practical way on the ground where you could see that we could’ve been negatively impacted by local decisions if we weren’t in the room. I mentioned Aries (Dela Cruz, then President of the Filipino American Democratic Club of New York) – he likes to say, ‘You either have a seat at the table or you’re on the menu.’”

On a walking tour of Little Manila Queens last fall, I learned just how much was at stake beyond just the local businesses. The tour was organized by FANHS-MNY and Sining Kapuluan, an LGBTQ-centered educational arts group, and was led by Xenia Diente, a Queens-based public art professional and board member of FANHS-MNY. What struck me then, as now, was that the history of the people and places within Little Manila Queens is very much a living history.

While certain landmarks, such as the Bayanihan Community Center and the community health initiative Kalusugan had been shuttered, most of the stops on the tour – such as Sonia & Friends Beauty Salon and Topaz Arts, a gallery and performance space founded by artists Paz Tanjuaquio and Todd B. Richmond – were places that bustled with the energy of a community able to connect, engage, and innovate together. What was happening in these spaces was a reclamation of the Filipino indigenous value bayanihan – the belief that we’re all connected; that we don’t get to where we are on our own; and that we have a responsibility to each other and to the world we live in.

In 2020, communities like Woodside are being threatened by forces larger than developers – a global Covid-19 pandemic that has resulted in the deaths of over 245,000 Americans so far; the killings of African Americans, including Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tony McDade, and the sustained protests since the summer that have made Black Lives Matter (BLM) now the largest movement in U.S. history; and deepening political polarization during, arguably, the most important modern presidential election to date. Bayanihan and the surge of similar mutual aid efforts in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities could be seen as a radical departure from the values of individualism and free-market capitalism promulgated by the dominant culture. But these community-based efforts have been critical with the increasing socio-emotional and economic toll of the pandemic and the recession.

FANHS-MNY board member Diente is currently an artist-in-residence at The Laundromat Project, committed to societal change by supporting artmaking, community-building, and leadership development of multiracial, multigenerational, and multidisciplinary artists and neighbors across the city. Along with fellow artist Jaclyn Reyes, she launched Little Manila Queens Bayanihan Arts, raising awareness about the cultural history and immigrant stories of Filipinos in Woodside as well as building communal relations between artists and Philippine businesses.

They have organized community events with local artists, including the weaving activist Cynthia Alberto, who founded the Brooklyn-based studio Weaving Hand and who led a free outdoor “Weaving Together” workshop outside K’Glen Deli & Sari Sari store on 65th Street. And when Queens became the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic, they launched the Meal to Heal mutual aid effort with the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns-Northeast, and FANHS-MNY to support Filipino-owned small businesses and essential workers, including nurses and other healthcare professionals at three nearby health facilities – Elmhurst Hospital, The Rogosin Institute Queens Dialysis Center, and Regal Heights Rehabilitation and Health Care Center.

Diente and Reyes also worked with artists Hannah Cera, Diane De Leon, and Ezra Undag as well as the Amazing Grace Restaurant and Bakery on a “Mabuhay” mural, unveiled on June 12, 2020, Philippine Independence Day. Reyes mentioned that both Cera and De Leon are high school students who were learning remotely and working at Amazing Grace through the height of the pandemic. The restaurant is owned by De Leon’s parents (her mother is a nurse as well), and Cera’s parents also work at the restaurant and in healthcare. Mabuhay is a Filipino expression that has many meanings: cheers, welcome, may you live. The mural – located at the southeast corner of 69th Street and Roosevelt Avenue, a common crossroads for immigrants in Queens – honors the spirit and service of Filipino businesses and healthcare workers on the front lines of the Covid-19 epidemic.

Diente spoke about another initiative that developed from the mural project: “At the unveiling ceremony, we invited Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer, who after seeing our handmade Little Manila street sign, made a commitment to make that street sign official. Following the unveiling ceremony, we launched the Little Manila Street Co-Naming Initiative, a campaign to not only have a Little Manila street sign installed, but a community awareness-raising campaign to encourage civic engagement in the Filipino community.”

The initiative proposes that an honorary street sign “Little Manila Avenue” be placed in Woodside at the corner of Roosevelt Avenue and 70th Street to recognize the contributions of the Filipino community to the neighborhood and to New York City immigrant history. So far, over 3,100 signatures have been collected in an online petition.

“Currently, our petition is being processed,” said Reyes of Little Manila Queens Bayanihan Arts. “The city has put a pause on street co-namings due to Covid-19, but we are hopeful that the sign will be installed next year.”

Beyond the local efforts in Woodside, Filipino activists have been working with other communities on intersectional issues, such as systemic racism and mass incarceration. Panelist Kalaya’an Mendoza is co-founder of Across Frontlines, which trains human rights defenders in anti-oppression work, nonviolent direct action, holistic safety and security, and movement building. He has been a human rights activist for over two decades, organizing with communities across the globe on human rights issues, from Tibetan Independence, to LGBTQ rights, to indigenous sovereignty at Standing Rock, to Black Lives Matter rallies in Ferguson and Charlottesville. He spoke about working in solidarity with the Black Lives and Black Trans Lives Matter movement, particularly during the protests that erupted in New York City and around the country in June.

He observed: “What we’re seeing right now is a reimagining of what the world can look like when our communities come together to not just fight alongside one another, but to build and reimagine a world where justice and dignity is experienced by everyone … One thing I know for sure is that this deep sense of community care, solidarity, and resilience is an ancestral gift left to us. This was the only way our ancestors were able to fight colonizers for so many centuries. It’s a gift and a legacy that they have given us to be able to continue the work moving forward.”

Mendoza also stressed the importance of those who’ve been doing the work for a while to support, mentor, and guide newer activists. He highlighted a few of the emerging Fil-Am activists who have been supporting the work of Black Lives and Black Trans Lives Matter activists in New York City, including Rohan Zhou-Lee, who organized and drew over a hundred people to the first-ever Blasian March, a Black, Asian, and Blasian solidarity rally.

I had met Zhou-Lee for the first time, training with Mendoza on safety and security for New York City’s solidarity action with the March on Washington back in August, then again as part of the street marshaling team at the Blasian March. They attended the virtual panel as well, and we caught up with each other afterwards to talk about what it meant to discover the Filipino part of their identity, the evolution of their activism, and about the experience of organizing the Blasian March. (You can listen to the full interview here.)

Zhou-Lee is of mixed Black, Chinese, and Indian heritage and found out about their Filipino ancestry right before college. Their mother and aunt were cleaning out their grandmother’s house in Florida when they came upon a family bible. Tucked away inside was the birth certificate of one of the family’s ancestors from Barbados, which read, “father, Scotland; mother, Philippines.” It was an important discovery, and for as much as some people would tell Zhou-Lee it didn’t “count” since it was so far back in their line, for them, “it’s like the fact that I now know this little bit of my ancestry, that’s one little bit of me that’s been decolonized.”

Zhou-Lee envisioned the Blasian March after witnessing some splintering in the community as the BLM protests continued into the fall. Black activists wondered where the Asian activists were, while Asian activists felt invisible as allies; some Black women and trans people also felt marginalized from actions that focused on justice for straight Black men. But Zhou-Lee believes these struggles are intersectional and therefore that “our power is intersectional, symbiotic. Miseducation has led to the myth that the Asian story and the Black story are mutually exclusive … I personally am working on doing more Blasian March actions, but I don’t want to be the only person. I hope to see other organizations figuring that out, realizing that these divisions are artificially erected by white colonial institutions. And marching side by side, in person, is the best way to undo that.”

The Blasian March took place on October 11, coincidentally falling on the sixth anniversary of the murder of 26-year old Filipina trans woman Jennifer Laude by U.S. Marine Joseph Scott Pemberton in Olongapo City, Philippines. It was a case that had sparked outrage and protests by activists in the Philippines and in the diaspora – not just because of Pemberton’s defense (that he had felt “raped” by Laude for performing oral sex on him without disclosing that she was transgender), his lenient sentence (12 years, later reduced to 10), and Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s pardoning of Pemberton in September, but also because of the larger issue of the U.S. military presence in the Philippines and policies such as the Visiting Forces Agreement, which gives the U.S. government jurisdiction over visiting U.S. troops and limits the ability of the Philippines to prosecute those accused of crimes on its own soil.

While Zhou-Lee didn’t initially intend for the Blasian March to coincide with the anniversary of Laude’s death, they reflected that “it was the best day to have a march for her alongside Black trans women and to uplift her name alongside the other trans people who have recently been murdered by white supremacy.”

For another activist whom I had a chance to interview, Kris Celestino Cornish Carrera-Vuelta (known as Kino in community), the historical and continued violence, bloodshed, and grief in Black and brown, queer and trans communities is a reminder to pay homage to and rise in solidarity with others in demanding equity, rights, and the “liberty to be, to breathe, to live.” Cornish Carrera-Vuelta was born in Pampanga and raised in Pangasinan, Philippines, before immigrating to Chicago then moving to New York.

They trace their lineage to Black and Filipino ancestors as well as queer and trans elders and descendants. In these challenging times, they are reminded that “there is also joy and an abundance of collective communal experience and a well of knowledge that we can pull from as descendants of powerful Black and brown people … this is such a humbling time and a perfect opportunity for us to get in touch with our roots and our history and to genuinely educate ourselves and put into action the wisdom and knowledge we receive.”

When Cornish Carrera-Vuelta moved to New York, they connected with and grew into their activism through the Filipino women’s rights alliance, GABRIELA New York, and the Safe OUTside the System and TransJustice collectives of the Audre Lorde Project. A longing for a more queer/trans-centered space led them and other similarly-identifying kin to birth the collective Sige! LGBTQ in 2018, serving to create a culture of support and empowerment for Filipinx queers and trans here in New York (sige, a Filipino word, translates to “Go on” or “Go ahead”).

In the context of a larger history of activism, Cornish Carrera-Vuelta spoke of embodying both the kind of masculinity their grandfather and namesake Celestino exuded – “a tenderness and warmth, welcoming of love and trust necessary to the patriarchy” – as well as the “matriarchs in my life who have allowed me to breathe, and live, and be, and to stand tall … My work is to be the mirror that possesses my people to see and feel and be in their own power because of the longstanding history in our robust bloodline. There is an intersectional, intergenerational, and international range of solidarity happening. Stay Vigilant. Stay Active. And pay it forward.”

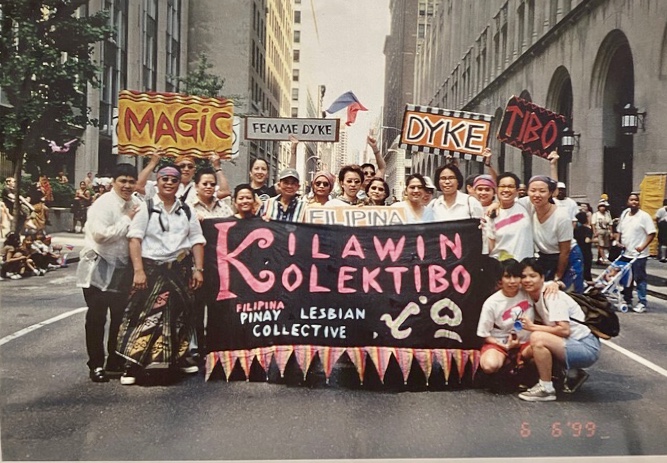

The FANHS-MNY panel highlighted this tradition of Filipino activism. While it may seem like a long struggle, fighting similar battles over and over, activists like Desireena Almoradie who founded the first Filipina lesbian collective in the U.S., Kilawin Kolektibo in 1994, reminded audience members that something like the concept of intersectionality didn’t even exist in the gay rights movement back then. “So, you couldn’t be gay and Pinay, you couldn’t be gay and Catholic, you could just pick one. But because of who we were, we couldn’t just pick one, right?” Almoradie said.

She shared a story about how she and a dozen or more of her friends would go to a gay bar, and people would stare at them as if they “had two heads … It was kind of an anomaly, and you felt that in some bars, people weren’t really interested in seeing Asian lesbians – specifically Pinay lesbians who were speaking Tagalog and being themselves.”

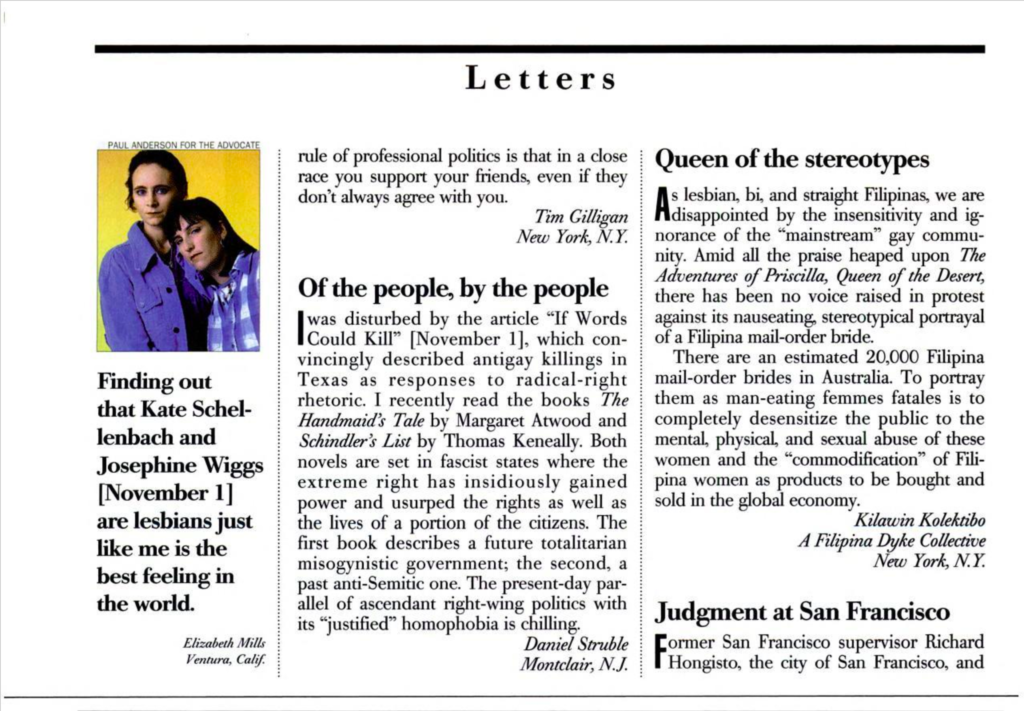

More significantly, while they were among the initial supporters of the groundbreaking film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, which sought positive cultural representation for queer and trans people, members of Kilawin Kolektibo had to issue a missive in the influential LGBTQ publication The Advocate about the portrayal of the Filipina character, Cynthia, in the film.

Almoradie explained: “We were forced to be activists because no one else was gonna speak for us.”

Luis H. Francia, the award-winning poet, nonfiction writer, and adjunct professor of Filipino language and culture at N.Y.U., also talked about what drove him to activism – the question, Why were Filipinos, our culture and people, invisible in the U.S.? He came to realize that it was because something as critical to our understanding of the relationship between the Philippines and the U.S. as the Philippine-American War was never taught in schools in either country. It was “basically forgotten, ignored, and marginalized. And so, when you marginalize the origins of the history of a whole people, then you marginalize them as well,” Francia explained.

For him, the pen has always been his instrument as an activist, whether it was “writing the wrongs” of the Marcos dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s or the current authoritarian regimes of Donald Trump and Rodrigo Duterte.

Indeed, Francia along with writers and academics Nerissa Balce, Neferti Tadiar, and Gina Apostol, are among the New York-based activists in the international Malaya Movement for democracy and against fascism in the Philippines (full disclosure: I am on Malaya Movement-Northeast’s legislative advocacy committee). Since 2016, the U.S. has provided over $550 million in aid to the Philippine military and police, not including arms sales – despite well-publicized documentation of state-sanctioned and politically motivated killings, mass displacement of indigenous people due to aerial bombings, the repression of press freedom, and the harassment of human rights defenders under the Duterte administration.

Malaya Movement (along with the Communication Workers of America, the Ecumenical Advocacy Network on the Philippines, International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines, Kabataan Alliance, United Church of Christ Justice and Peace Ministries, and United Methodist Church General Board of Church and Society; the full list of endorsers may be found here) have led the charge in lobbying Congressional representatives “to suspend United States security assistance to the Philippines until such time as human rights violations by Philippine security forces cease and the responsible state forces are held accountable.”

Advocacy and lobbying efforts have been met with significant successes. In July, 2019, the House foreign affairs committee held a hearing on Southeast Asia where attendees questioned the role U.S. taxpayer money played in human rights abuses. In January, 2020, Congress passed a bi-partisan resolution condemning the Duterte administration’s targeting of political opponents, including Philippine Senator Leila De Lima and journalist Maria Ressa.

In July, 2020, Representative Jan Schakowsky of Illinois initiated a letter that was signed by 44 other Members of Congress and sent to Philippine Ambassador to the U.S., Jose Romualdez, urging the Philippine government to rescind the newly-signed Anti-Terror Law. Most recently, the Philippine Human Rights Act (H.R. 8131) was introduced on the floor of the U.S. Congress in September by Representative Susan Wild of Pennsylvania and currently co-sponsored by 29 other members of Congress.

Documenting social injustices as they happen demands accountability in the present as well as in future historical records. Writing down our stories also makes the invisible and forgotten seen and remembered. For example, thanks to writers like Carlos Bulosan and Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, we know of the Manongs and have a sense of their lives and their struggles as migrant laborers on the West Coast in the first half of the 20th century. But, as Professor Francia related in his example of recently stumbling upon the story of Manong Pedro Penino, who enlisted in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War and also returned to the Philippines to fight against the Japanese in World War II, there are so many stories and layers of history, including the history of Filipino activism in America, that we have yet to uncover.

He advises the students in his language and culture class to interview their parents, to find out why they moved to the United States. Francia referred to a Tagalog saying (often quoted and attributed in the popular imagination to Jose Rizal), “Ang hindi lumilingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makakarating sa paroroonan. (If you don’t know where you came from, you won’t know where you’re going)”. It is an apt reminder of why Filipino American History Month is celebrated and also about what the work of activism is.

Today’s Filipino American activists stand on the shoulders of all who came before them. As many of the long-time activists emphasized, it isn’t about what any individual can achieve in their lifetime, but how an enduring movement can, over time, realize a more just, equitable world where we all can live with dignity and in radical joy and love.