While I was doing witness work around violence, I was also always living in a shadow space where I could be safer, where I could be protected, where I was known, where I could not be misread

June 16, 2021

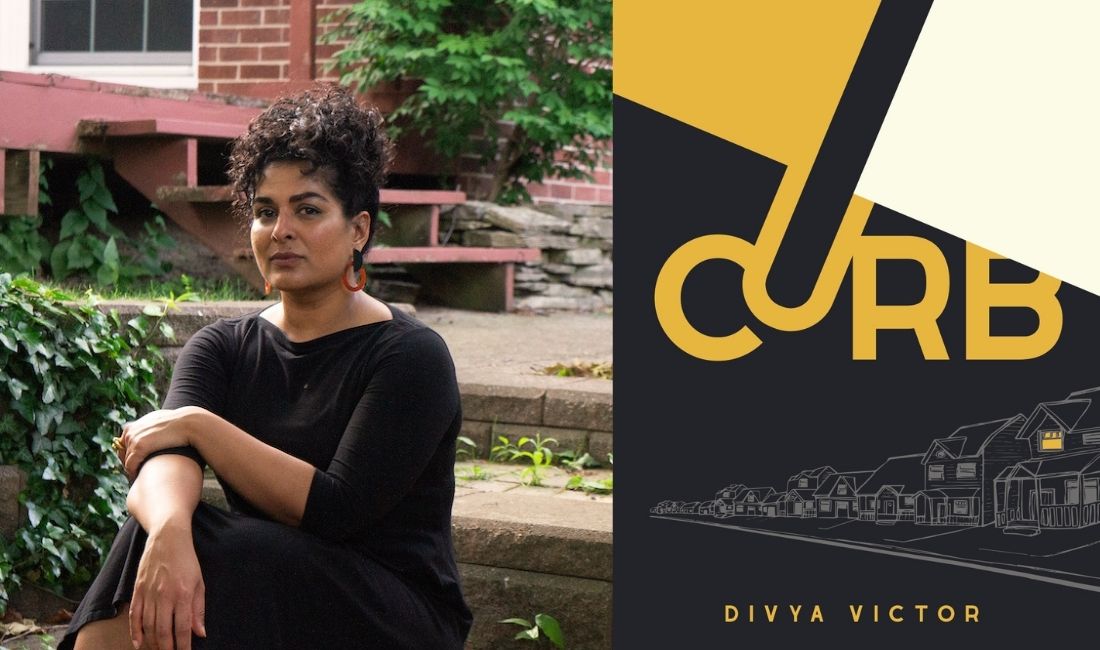

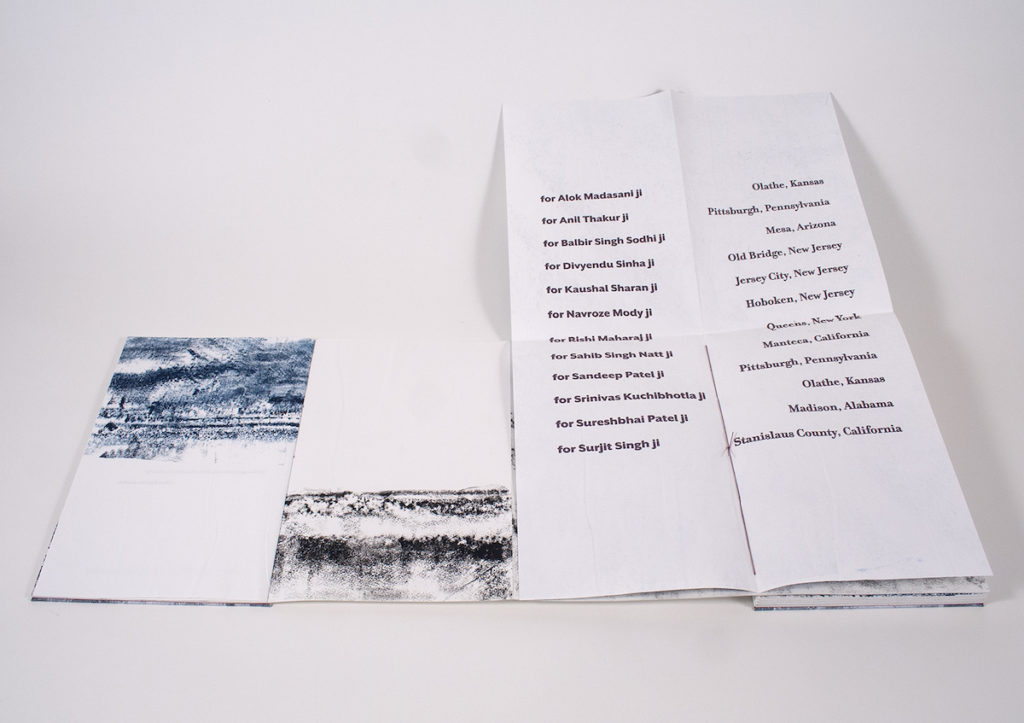

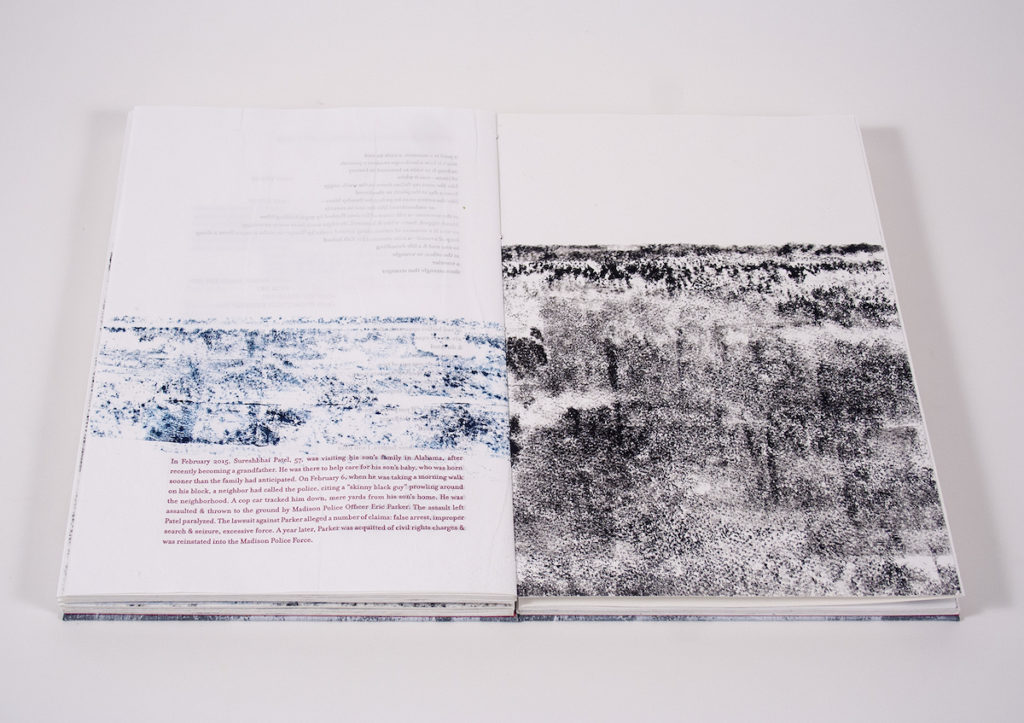

Divya Victor prefaces her new poetry collection, Curb, with four names—Balbir Singh Sodhi, Navroze Mody, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, Sunando Sen. By invoking the names of these four Indian American victims of racist violence in a post-9/11 America, Victor refuses to let their names disappear into mere statistics. In Curb, the South Asian immigrant becomes a subject of study through the speaker’s body (physical and conceptual) as an immigrant in Trump’s America.

While these names only appear again in the context of a few poems, they haunt Victor’s collection with their affect. The collection begins from the individual experience of the speaker and finds itself moving towards the exterior, collective experience.

As Victor explained to me over Google Chat, writing Curb was her way of remaining in the eternal cycle of debt to those she learned from; a debt that can never truly be repaid. This is also her way of creating coalition in the imaginary which, according to Victor, is a much needed coalition of the collective.

—Sanchari Sur

Sanchari Sur

Before Curb existed as a book, it existed as an art exhibit. And that was a few years ago. So, it evolved from artist’s book to poetry collection. Can you speak to that process of evolution?

Divya Victor

In 2017, the printer Aaron Cohick came to me with an idea. I’ve known Aaron since I was an undergrad. We spent a lot of time on stairways, smoking cigarettes and drinking beers and having these big plans for what we could do. And he kind of kept track of them.

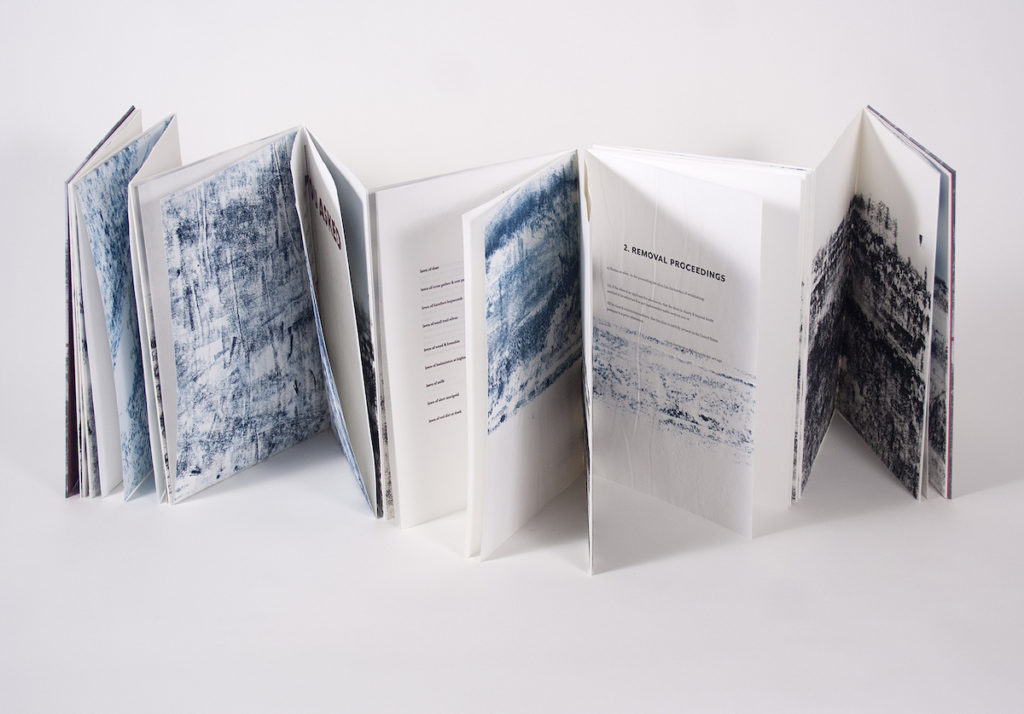

He came and said, I want to do a fine press edition through letterpress of something that you would make responding to where you are right now. And it was a really terrifying moment for me because we had just come back to Trump’s America [from Singapore]. And I had just become a mother. And so I was feeling a kind of twinned fear; one on my own behalf, and one on the behalf of my newborn child. And I said to Aaron, I don’t think you’re going to love the content because it’s just going to be very difficult. And he said, I think we should do it. And so, we started having conversations about the form of the book, and the foundation of Curb in many ways was laid in those conversations.

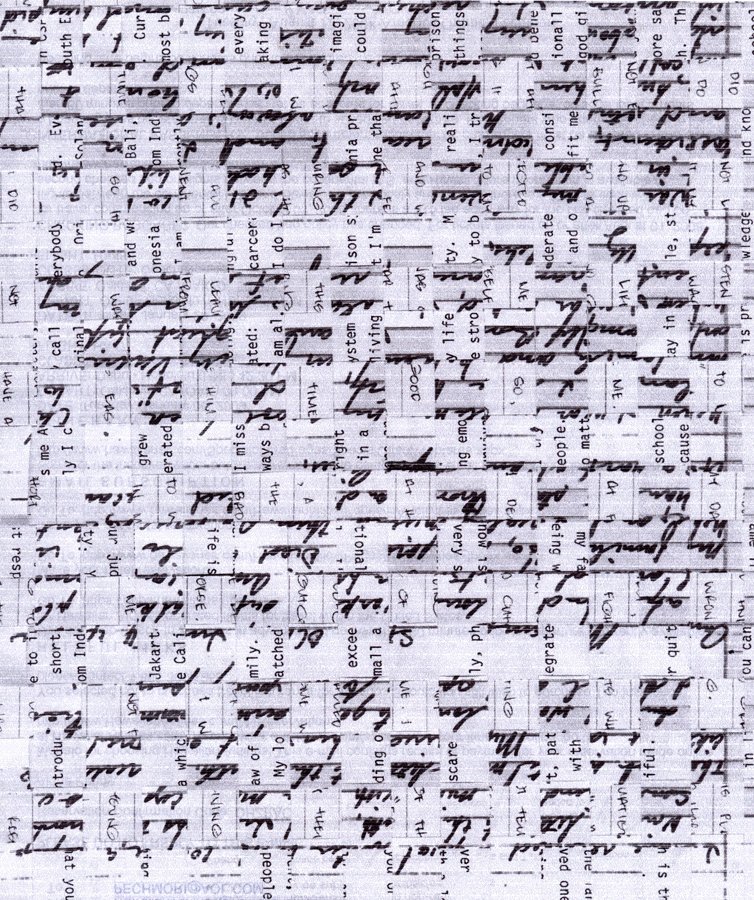

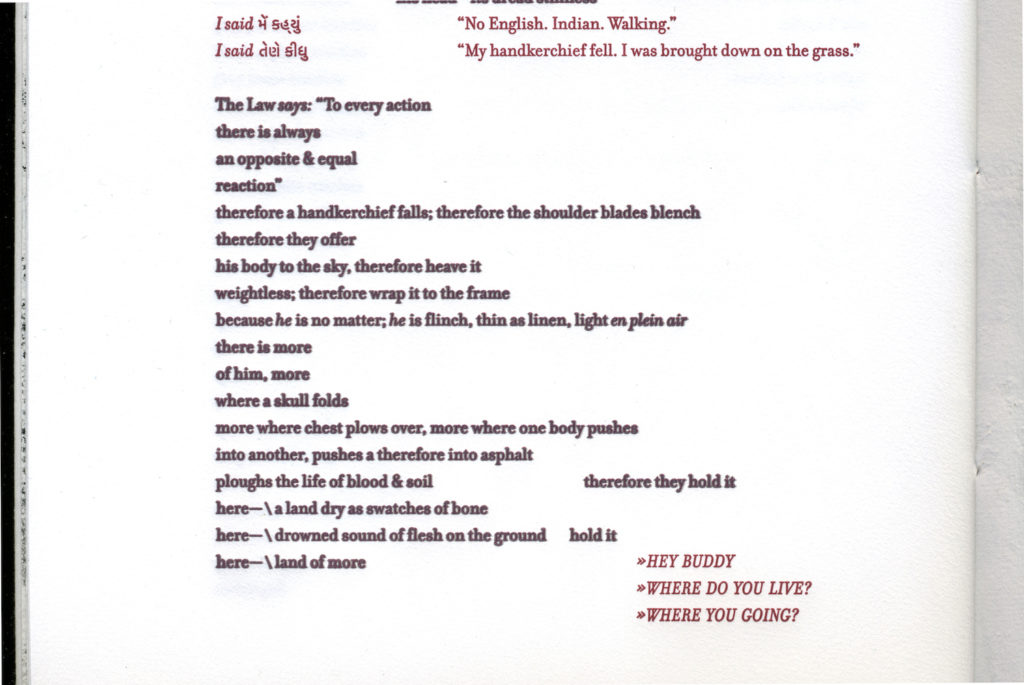

We wanted to make a book that would make the reader extremely alert to the work of reading. I was interested in how humans are read and misread all the time, particularly in public spaces, and how misrecognition is fatal. I was interested in how many cases there were of Indian immigrants, and descendants of immigrants, who are perceived as terrorists. And that was fatal. So, we wanted to make a book that was interested in misreading, difficult reading, effortful reading. And, we wanted to make a book that was very conspicuous and large.

The artist’s book is an accordion fold that has sections that open up vertically as well as horizontally. When you open it up, it can take up an entire dining table. These vertical sections open up like massive maps, because I was thinking very much about the post-1965 move to the United States that many South Asian Americans undertook, and how they would have to engage in map-reading all the time to find their way around everyday places. Reading maps in public spaces is one of the most pronounced ways before the digital era where you would announce your place as a stranger. It’s this conspicuous act of reading that then allows others to read you in that public spot. The book started enacting some of that conspicuousness and effort in navigating public space. So, [the art project] started as that.

The artist’s book was invested in public space, [and in] witnessing all violence in the public environment. But I hadn’t quite asked the question of them: How do they witness it indoors, and how do we move that witnessing to the interior? And so, I started writing the interior sections. And together, the interior and the exterior acts of witnessing and how those acts of witnessing shaped me, my consciousness, my subjectivity, my identity—that then became the Curb that you read.

SS

At the back of the book in your “Notes and Objects Cited,” you state that “A reader might find the location of any of the marked poems in Curb using the facility at www.gps-coordinates.net.” The coordinates inside Curb are a new addition—they were not part of the original project. It’s almost as if the book itself becomes another project for the reader. Do you want to speak a bit about the coordinates and their place in the book? What was your thought process behind including those coordinates specifically?

DV

It’s a good question, because one of the things I am most frustrated about in our current subaltern writing is how easy it is to abstract subaltern writing and experience, and to diffuse it into a kind of generalised trauma.

In the edition of Curb that you have, I wanted the particularities of the violence to be rooted in and anchored to location, because what I’m trying to write is a spatial theory of the nation that has been stained by blood, right? The coordinates pin us to the historical moment. They don’t allow us to abstract violence away from these particular bodies, these particular men who were assaulted or killed or apprehended by police. So for me, the coordinates were one way of saying, this happened here. And you are here now, and this is an act of witness.

The coordinates across the book take us to these sites of violence, but they also take us to sites of memory. And sites that move us between a site of violence and a site of memory. I wanted to show how as a poet, while I was doing the kind of witness work around hate crimes or violence, I was also always living in an erstwhile space or shadow space where I could be safer, where I could be protected, where I was known, where I could not be misread.

And so the book moves often between, let’s say, a site of microaggression on my front lawn, and then a front lawn in a place back in India where I was a child, where I felt seen or recognized and understood.

SS

So basically, you as a poet are setting up these memorials that readers can visit. The way I see memorials working is, I’m witnessing this has happened, and we’re also remembering this person’s life at the same time.

DV

Yeah. I think memorials are fascinating because they activate memory that goes beyond that event, right? It connects the particular events that we’re thinking about to a larger historical trend, that are set to the frequency of certain kinds of events happening again and again.

SS

Yeah, but I think memorials also have the tendency to allow people to forget. That would be harder to do with the book, I think, because the act of reading is far more active than visiting a passive memorial.

DV

The kind of tourism of a vigil is not what I am interested in, right? I am not interested in holding up candles in the middle of the night gazing upon the face of a stranger. That, to me, does not produce a shift in consciousness because as people who live in these privileged sites, I think our subjectivity is formed by the politics of pity, by saying ‘poor thing, what a brutal way to end a life and what a brutal way to go.’

Our survival is sort of a macro political pleasure, right? You’re like, ‘Yeah, not me, not me.’ And I think the [physical] memorial risks that kind of ‘thank god, it’s not me’ passivity.

SS

This allows me to segue into the structure of the book itself. I noticed that each part of your book has its own conceit, its own way of working. It’s almost like the different sections are these different art exhibits in one space. Can you talk to me about the structure?

DV

When one is assembling the book, one is really just trying to hold oneself together. And I often find myself feeling like I have to take an account of who I’ve been as a thinker and a writer for three years or so. It’s a real collisional experience for me.

But I was studying my book the other day as a reader. And it occurred to me that the book really starts with a kind of historical statement about settlement. It takes a full century view, in a one page summary, just through the interplay of the words “settle” and “settlement.” It begins with birth—my experience giving birth to my child in Singapore. And then, the book ends with the serial poem “Estates,” which is about funeral rites and practices of dying in a “multicultural” medical environment, which supplies so-called customizable funeral experiences in hospices and hospitals. And between these practices of birthing and dying is the work of living, as well as the efforts of living that are particularly taken up by immigrants.

And, we move further and further away from my context into exterior context. So, if the location of “Hedges” is my body, my abdomen, “Plots” takes us to the threshold of my house, my lawns, my yard. “Petitions (For an Alien Relative)” takes me further afield until we are in “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony).” The testimony is a courtroom scene in New Jersey, which to me is the farthest away from something like home. It’s a legal environment where we are abstracted into a series of precedents. Being legal subjects is the farthest thing from being loved.

That’s how I imagined [the book], as a series of distances from the self.

SS

You mentioned the poem “Settlement” earlier. I’m interested to hear and understand your conceptualization of South Asian immigrants as settlers. So, in my research as a doctoral student in Canada where I study Canadian identity in the context of Canadian multiculturalism—which I know is very different from the formation of American identity in the context of multiculturalism in the United States—there is a similar conflation, I think, when immigrants are called settlers.

DV

I don’t claim that South Asian immigrants are settlers, but I am also interested in the South Asian idea of settling down.

At the level of language, I’m interested in querying what settling down is and how it produces a complicity with settler desires in this nation. So, to settle down is a certain kind of heteronormative pursuit of private property, and I think that pursuit is very much complicit with a settler ethos that suggests that we have a kind of manifest right to this land. And I really want to emphasise that as immigrants, we don’t have a right to this land, and that even while displaced, and even while turned out or in exile from our so-called places of origin, we still cannot forget our roles as guests, as people who are very much here in a pursuit of a life way that is in direct conflict with the life ways of the Indigenous peoples who were on this land way before us. I think that is something where I am trying to hold intention.

SS

Okay, that was my misunderstanding because of the way the word “settle” was being used. But this leads very nicely into the second part of my question. It’s only in the past decade that some South Asian Canadian writers are trying to negotiate their relationships to the Indigenous peoples in Canada. In your poetry collection, there were two poems that seemed to refer to a similar negotiation. One was “Milestones: A Theory of Marking/ Being Marked.” You write about Lake Michigan and use the Ojibwe word, mishigamaa. And then in “Beds (Clay),” you elaborate on the Indigenous connection to “sioux quartz” in your citation at the end of the book. These were the only two points in the book where you refer to the Indigenous history and ties within America. In these poems, what were you negotiating, and what was your relationship to that negotiation while writing this book?

DV

I am interested in the names of places. I am interested in how the names of places change and become vehicles for hegemony. So, how is power represented in a certain place at a certain time? We see this all over in the resurgence of a nationalist identity in India (Chennai, not Madras; Mumbai, not Bombay). And that’s one thing that interests me because I think that our idea of identity is so connected to place names that it produces a kind of chauvinism or essentialism about our identities that is very silly. I mean, I think about why people call me Indian and Indian is such a recent construct, right? I’ve started identifying much more as a Tamil person because my attachment is to cultural practices and linguistic practices much more than to the idea called India.

I also think there is a lot of work to be done in creating imaginative bridges between Indigenous practices and South Asian practices that help us understand our obligations to the land. So, in the poems that you’re mentioning, in “Milestones,” I was trying to understand how I embody my guest-ness in this place. The process for that piece was, I would enter my study every day and actually shape myself into an abstracted shape of a milestone and face varying directions to these water sources—Lake Michigan, Kaveri river—to perform a kind of constant reorientation that feels very native to a guest status, right? So, the guest as compared to a nomad, or a guest as compared to an immigrant. And I think I have become more curious about how I can behave more like a guest, as compared to someone who is constantly insisting on my right to be here.

SS

This reminds me of your poem, “Gulf,” which talks about violence against land in another way. You write about uprooting the land to lay down cables so that people in India can watch the Gulf War, which is happening elsewhere, which is a very different way of taking land or using land, and not exactly the way we understand colonialism, but the poem has a colonialist underpinning. At the same time, you’re writing from a location of guest-ness in America. Can you talk about the relationality between that location and writing this poem the way you have?

DV

The whole book is interested in the construction of land, who it belongs to, how it’s represented, who gets to occupy it, how those constructions and those policies around it relate to the construction of a stranger, to someone who does or does not belong, who can and cannot be recognized. And I started asking myself, what were some of the earliest experiences I had where I did not feel like I had a naturalized or immediate unmediated relationship to my space? When did I first start feeling like everything that connected me to my space was starting to be mediated? And [the experience within that poem] was one of the earliest memories I have of feeling separated from what should have been my land. And, that was [through] CNN.

I think the consumption of the Gulf War separated me from my land. As I was querying that feeling, I recollected that our township at that time was actually being ploughed and opened up and cracked open for these cable companies. There was a kind of a conquest of the imagination, a kind of conquest that led to a compulsory production of sympathies with these alien empires.

As a child, I knew nothing about the contours of that war. And yet, I was convinced that the US was somehow doing the right thing, protecting civilization itself. And that kind of takeover of my relationship to land, I think that’s what “Gulf” introduces in the book. It’s the Gulf, of course, as in the Gulf War, but also the gulf between myself and my land, the thing I’ll never get back.

SS

We talked about language earlier. And maybe, we can go back to language. There are two interesting things that you do with language in the book. One, you use it to subvert formal language. For example, in “The Ankle,” you have the clinical structure of what seems to be a death certificate, but it overflows the balance as a poem because it tries to articulate a history of racist violence against South Asians in the United States. At the same time, you also have the written script of different languages such as Tamil, Gujarati, Hindi, Urdu, interspersed with English. Can you speak to the way you use language in the collection?

DV

I am very, very interested in the language of bureaucracy, and every time we encounter a bureaucratic form, it’s a scene of subjectivation for me, because you’re hailed in a particular way, you’re named in a particular way, and you have to see yourself in a particular way. So, the language of these forms becomes a kind of recurrent violence in my life—it’s like constantly writing autobiographies under duress. As you know, anyone who knows immigrants, this is such a part of our lives, constantly writing yourself into forms.

I engage with bureaucratic documents as a way to rehabilitate my attachment to their language, and to tell a story in the midst of my bureaucratic subjectivation. So, I’m always sort of interrupting these documents to offer something else.

In Curb in particular, I often use formal interruptions of cited language or typography in how I am reporting scenes. I am reporting someone else’s memory or reporting from my own last memories from sites I have departed from through these forms because of these bureaucratic structures that they uphold.

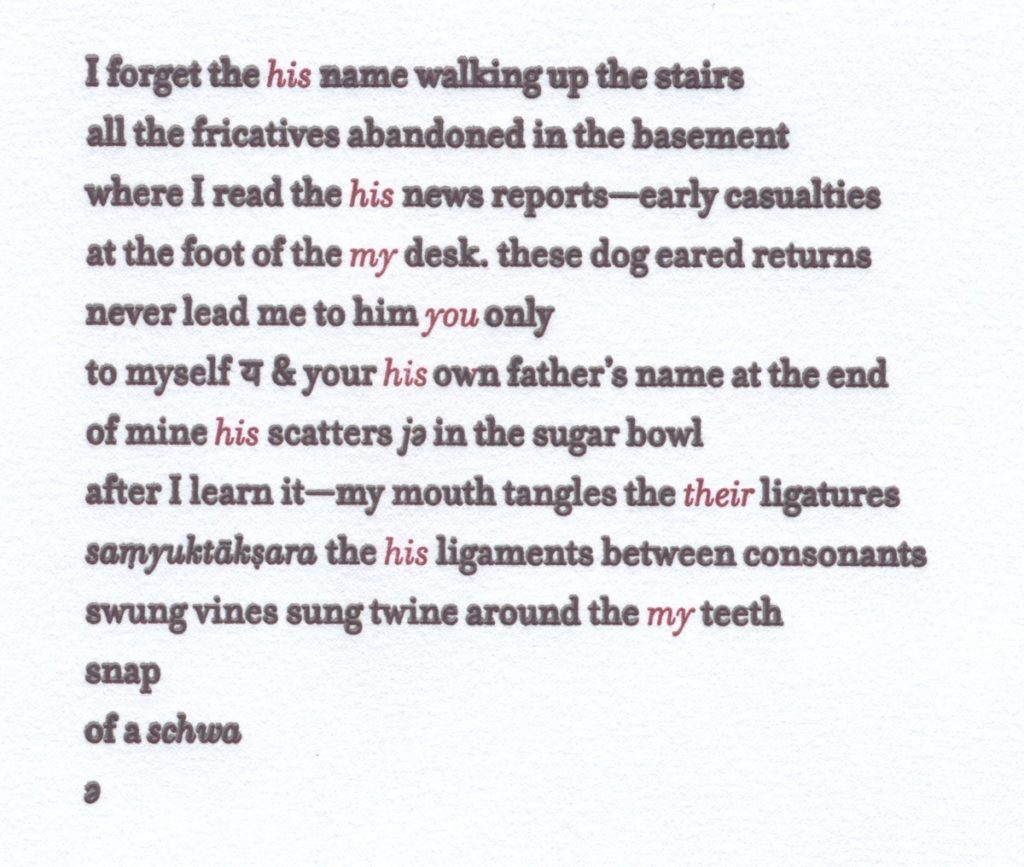

In terms of [the] tri-glossic, or quadra-glossic environment of Curb, English is one among many languages. And I’ve always encountered it as such in my life, as a Tamil speaker, as someone who knows Hindi and understands it and can read it very slowly, and also someone who grew up in these tri-glossic environments both in India and Singapore. It feels I am more at ease when I can think in multiple languages, across trans-linguistic puns or homologies between homophones in two different language environments. I think it’s the one place in which I can be boundary-less.

But in addition to that, I think in Curb, like in the Divyendu Sinha poem [“Pavement”], the particular relationship between a va and a ya [in] Hindi—that particular vya blend—is the only thing that connects me to Divyendu Sinha, because of my [first] name.

My alertness to that was my way of inscribing again and again in the poem that even though I’m writing about this man who is my kith, he is still resolutely a stranger to me. We ultimately have nothing in common but this blended consonant. That’s it. I know nothing about his politics, his values, his identity. So, I think language, particularly non-Anglophone languages, erupted when I was the most alert to the continued gulf between me and the people I was writing about.

I think I was producing a language environment that I can speculate that many of these men would have been comfortable in. I mean, if you’ve ever travelled in India, you know that every lorry driving by has twelve different languages on it. The highways are multi glossic environments. [Laughs]

SS

Let’s talk about the motif of water that shows up in your poems through boats, sailing, swimming. They seem to recur in relation to language almost as an act of transit, of fluid transitions that are always ongoing and never really complete. I am thinking particularly of the poems, “Milestone I,” “Locution/Location,” “Lawn,” and “Milestone 3.” Can you speak to the idea of using this motif? What is your relationship to water as a poet?

DV

Well, I’m a Pisces. So, water. [Laughs] Just kidding.

So, where I was born, Kanyakumari district is shaped by three water bodies: the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and the Arabian Sea. And I have very early memories of going down to the shore and being told by my family, this is who you are. And they would cup a handful of the soil and you could see the rust red, the kind of beige golden sand, and the black alluvial soil—to know that we identified as people from the Kanyakumari district because of the material exchange between water and land, the erosion of ancient formations that becomes our ground, right? That has always been a place of fascination for me. Even as a child, I spent the most amount of my time adding water to ground and making shapes sculpting, digging, making mud.

And when I became pregnant, I became uniquely aware of water in my body. And in “Thresholds,” I very much imagined what it means to contain the ocean as anyone who is becoming a parent through the relation to the amniotic. So, the oceanic and the amniotic are the two kinds of fluid engagements in Curb.

And you asked about my relationship to water. I am a coastal baby, I was born into a coastal community, and I lived on an island, Singapore, for so long. And my lineage hearkens back to those who identify as Mukkuvars. I was raised Catholic. I come from pearl divers, fisher people. So much of my early sense of myself comes from my grandmother’s stories about her father, who travelled between Kanyakumari and Ceylon, and making that crossing across the strait into Sri Lanka.

The notion of crossing water has been definitive for me. And I know that within the diaspora, particularly as it engages in the Caribbean, you have this fear of Kala paani [black water], which is rooted in the Hindu imaginary of purity. But for Catholics, the crossing of Kala paani is what gives us a certain kind of identity because of our missionary roots. And so, the fear is distinct, it’s different. We don’t share that fear.

SS

That’s interesting. I didn’t know about that distinction.

DV

It’s an assumption, right? I mean, growing up around Hindu friends and Hindu families who were very close with the suspicion around travel, is not something that was familiar to my family. The fear of travel was not foundational; it was more circumstantial or individual.

SS

Let’s talk about the “Notes and Objects Cited” at the end of the book. It seems to be very academic as it’s an academic practice to provide sources and explain ideas in detail.

DV

I can refer you to the quote by Sara Ahmed, “Citation is how we acknowledge our debt to those who came before.” And I began a practice of debt and how to stay within structures of debt, through citation practices in Kith. In Kith, I was returning to and referencing stories told to me by the matriarchs, and the sort-of feminists in my family, and I had no way of citing them in an academic position. So, I had to bring them into citational practices very explicitly so that I wouldn’t merely reproduce their stories without an apology.

And I continued that here as well. So you’ll see that sometimes I’m referencing personal narratives, sometimes scientific treatises, sometimes theory or news articles, and I really think it’s important to show our sources. I am moved both by certain rigors of what are now conventions of academic practices but I am also fascinated by debt, and how South Asians understand this eternal and ongoing structure of debt that we are in when we form collectives.

I will never be able to repay my debt to source X, Y, or Z, and to document that [debt] is my way of remaining in it. It’s also called gurudakshina, this idea of offering a fee for what I have learned.

SS

So, this is your way of offering your fee through these citations?

DV

I think so.

SS

What is urgent about your book in the current political moment? Why this book and why now?

DV

We are living in a time where the immigrant is seen as contagion, as threat, as a direct confrontation to what is imagined as America. [This country’s] nationalist and supremacist policies affect every single person’s life in the United States—[they] have produced agents for supremacy who are not only white, but who are also immigrants and folks of color, as is clear from the anti-Blackness in South Asian communities. These agents for supremacy are also Hispanic, Black, white [etc.] who imagine the immigrant as a threat to their life. We are living in a time where we have concentration camps at the borders.

And so, to write a book about the threat to the immigrant and about how white supremacy shapes citizenry, was absolutely urgent. [Currently,] awareness to hate is trending, but this book is entering a conversation that is at least two centuries old, about how we go from a place where we are loved and known, and entering a space where we are strangers and threatening. And that conversation is also about how anti-Blackness is produced, and about how anti-Asian and anti-immigrant sentiment is produced in this country. And all of those sentiments are in the service of supremacy.

When I think about ‘why now?,’ it is because we need to have coalitional efforts also in the imaginary, and in our relationships to each other that takes place within language itself. Yes, in protest, yes in policy, yes in legislative change, but also in the imaginary where so many of us live.