I want — Evanescence — slowly. After great pain.

“It was a year of brilliant water”

—Thomas de Quincey

I

Students of mist

climbing the stairs like dust

washing history off the shelves

will never know this house never

that professors here in glass sneakers

used window squares for crosswords

moving the weather from sky to sky

under their arms new editions of water

while mirrors left lying on coffee tables

tore the glare from the windows

and glued vanishing rainbows

to the walls the ceilings

will never know the sun’s quick reprints

2

It was a year of brilliant water

in Pennsylvania that final summer

seven years ago, the sun’s quick reprints

in my attaché case: those students

of mist have drenched me with dew, I’m driving

away from that widow’s house, my eyes open

to a dream of drowning. But even

when I pass—in Ohio—the one exit

to Calcutta, I don’t know I’ve begun

mapping America, the city limits

of Evanescence now everywhere. It

was a year of brilliant water, Phil,

such a cadence of dead seas at each turn:

so much refused to breathe in those painted

reflections, trapped there in ripples of hills:

a woman climbed the steps to Acoma,

vanished into the sky. In the ghost towns

of Arizona, there were charcoal tribes

with desert voices, among their faces

always the last speaker of a language.

And there was always thirst: a train taking me

from Bisbee, that copper landscape with bones,

into a twilight with no water. Phil,

I never told you where I’d been these years,

swearing fidelity to anyone.

Now there’s only regret: I didn’t send you

my routes of Evanescence. You never wrote.

3

When on Route 80 in Ohio

I came across an exit

to Calcutta

The temptation to write a poem

led me past the exit

so I could say

India always exists

off the turnpikes

of America

so I could say

I did take the exit

and crossed Howrah

and even mention the Ganges

as it continued its sobbing

under the bridge

so when I paid my toll

I saw trains rush by

one after one

on their roofs old passengers

each ready to surrender

his bones for tickets

so that I heard

the sun’s percussion

on tamarind leaves

heard the empty cans of children

filling only with the shadows

of leaves

that behind the unloading trucks

were the voices of vendors

bargaining over women

so when the trees

let down their tresses

the monsoon oiled and braided them

and when the wind again parted them

this was the temptation

to end the poem this way:

The warm rains have left

many dead on the pavements

The signs to Route 80

all have disappeared

And now the road is a river

polished silver by cars

The cars are urns

carrying ashes to the sea

4

Someone wants me to live A language will die with me

(once

spoken by proud tribesmen

in the canyons east

of the Catalinas or much farther north

in the Superstition Mountains) It will die with me

(Someone wants me to live)

It has the richest consonant exact

for any cluster of sorrows

That haunt the survivors of Dispersal that country

which has no map

but it has histories most

of them forgotten

scraps of folklore (once

in mountains there were silver cities

with flags on every rooftop

on each flag a prayer read

by the wind a passer-by forgiven all

when the wind became his shirt)

Someone wants me to live

so he can learn

those prayers

that language he is asking me

questions

He wants me to live

and as I speak he is freezing

my words he will melt them

years later

to listen and listen

to the water of my voice

when he is the last

speaker of his language

5

From the Faraway Nearby —

of Georgia O’Keeffe — these words —

Black Iris — Dark Iris — Abstraction, Blue —

her hands — around — a skull —

“The plains — the wonderful —

great big sky — makes me —

want to breathe — so deep —

that I’ll break — ”

From her Train — at Night — in the Desert —

I its only — passenger —

I see — as they pass by — her red hills —

black petals — landscapes with skulls —

“There is — so much — of it —

I want to get outside — of it all —

I would — if I could —

even if it killed me — ”

6

“I have no house, only a shadow”

— Malcolm Lowry

In Pennsylvania seven years ago

it was a year of brilliant water,

a resonance of oceans at each turn.

It’s again that summer, Phil, and the end

of that summer again: you are driving

toward the Atlantic, drowning in my

brilliant dream of water. I too am leaving,

the sun’s reprints mine. There are red hills

at the end of my drive through three thousands

miles of Abstraction, Blue — the Blue that will

always be here after all destruction

is finished. “Phil was afraid of being

forgotten.” But it’s again a year of water,

and in a house always brilliant with lights

I’m saying to a stranger what I should

have said to you: “I have no house only

a shadow but whenever you are in need

of a shadow my shadow is yours.”

7

We must always have a place

to store the darkness

but in your house all the lights are on

even during the day

The fluorescents you say

are like detergent

They whitewash the walls and the ceilings

Your vacuum sucks in half-shadows

from your carpets

and as you climb the stairs

the wax polishes the sound of your footsteps

What can I be but a stranger in your house?

My house is damp with decades in which

the sun was dark

I keep all my lights off

During the day I shut the blinds

No

Don’t even bring a candle when you come

8

You

sometimes suddenly

the son I’ll never have

Mediterranean boy

Icarus of the night

You drive your car

its wheel dying

on the platinum tar of tides

a highway on the sea

paved by the rising moon

Sirens whispering

on their lips the sinking

breaths of salt

whispering from Istanbul to Tunis

whispering their silver fractures

at the booths where your hand

rich with planets for coins

pays toll

your windows rolled down

the brine pouring its green change

into your car

9

“I want to eat Evanescence slowly.”

— Emily Dickinson

The way she had — in her rushes — of resonance —

I too — so want to eat — Evanescence — slowly —

in the near — faraways — of the heart. Like O‘Keeffe

also — in her Faraway Nearby — that painting,

this ghost-station — from where her Train — in the Desert —

at Night — will depart — its passenger — only I —

banished to the soul — of the desert — from its heart.

After great pain — a formal feeling does come — I —

the society — of that sheer soul. The soul selects

its own society: a formal feeling will come:

I want — Evanescence — slowly. After great pain.

So I refuse to be the only passenger:

I’ve bought tickets for us to Evanescence, Phil,

and you will be with me as we pass the ghost towns —

What views! Rock ruins of post offices. Brilliant,

Telegraph — we’ll pass them. There’ll be news from Carthage —

and then Tierra Blanca — the Train holding just us —

Immortality — and Fog — that blond conductor

who will ask — at Chance Village — for our tickets.

You come — punctual as a star! — to wave to the rich,

platforms across us stunned by their luggage. No god

would dare send them away empty, as usual

they’re inheriting everything, even hope. See,

there’s no end at the end, so you musn’t die, no,

not now, for our train has begun to move, wedding

the sky with a ring of smoke. The rich don’t see us,

though we throw roses at them, white and calico,

frail aristocrats of Time. It’s far behind now,

mere gold dust, the station of Faraway Nearby,

the rich invisible. And we are millionaires,

passing Pink and Green Mountains, painted just for us,

and other landscapes we own, Black Cross with Red Sky.

Black Mesa, Ghost Ranch Cliffs. Vast Nights of Lightning. Stars.

But your voice is choked, the whisper it was the last

time we spoke. “Let his voice not change!” I’d almost prayed.

You fall silent as I give our tickets to Fog.

When he leaves, we see Light Coming on the Plains,

the last painting we own. As it too vanishes,

you say, “You’re wrong. It isn’t that my voice has changed.

It’s just that you’ve never before heard it in pain.”

10

Shahid, you never

found Evanescence.

And how could

you have? You didn’t throw

away addresses from

which streets

departed, erasing

their names. Some

of these streets,

lost at junctions, were

run over by trains.

At stations

where you waited, history

was too late:

those trains

rushed by and disappeared

into mirrors

in which

massacres were hushed.

No reporters

were allowed

in. You waited to hear

the glass break,

but no train

came back. And then

on those mirrors

curtains

were drawn. You didn’t

throw away addresses,

and some

of these streets

were picked up

at exits

that took them

to cities miles

under the ocean

from where postcards came

with Africa washed

off them.

You didn’t throw away

addresses from which

streets

departed. There’s

no one you know

in this world.

11

“Phil was afraid of being forgotten.”

It’s again that summer, Phil, and the end

of that summer again. Good-bye, I am

saying to those students of mist, leaving

Pennsylvania with the sun’s reprints.

Ahead is a year of brilliant water —

there’s nothing in this world but hope: I have

everyone’s address. Everyone will write:

And there’s everything in this world but hope.

Reprinted from A Nostalgist’s Map of America: Poems by Agha Shahid Ali. Copyright © 1994 by Agha Shahid Ali. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

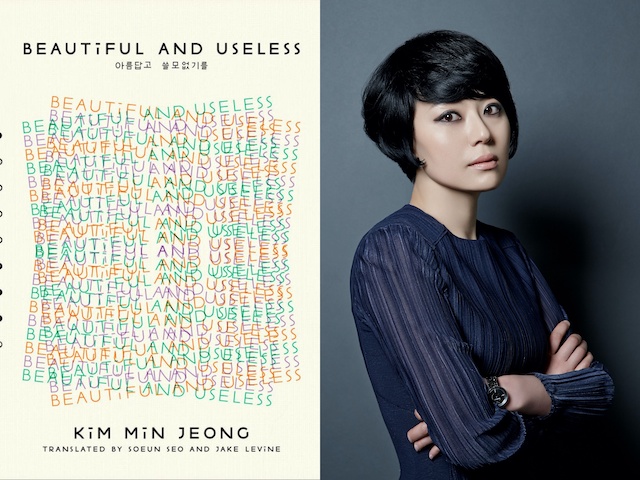

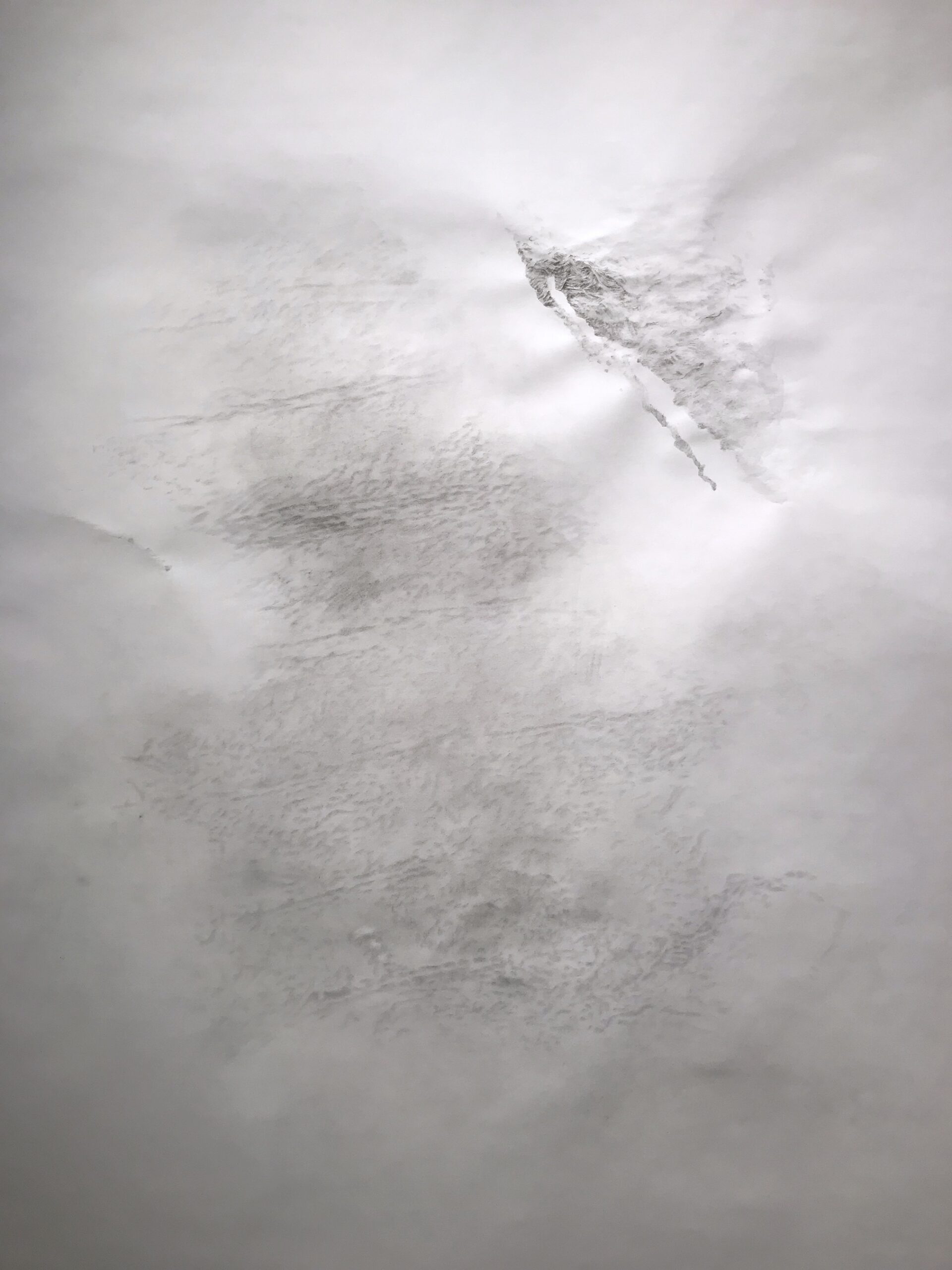

This piece is featured in the Climate notebook, which features art by Katrina Bello. Min Hyoung Song and Jennifer Chang discuss the poem in their correspondence “A Migratory Imagination.”