Former programs associate Nadia Q. Ahmad on work, rest, and AAWW’s fabled green couch

December 15, 2021

Editor’s Note: As the Asian American Writers’ Workshop celebrates its 30th anniversary, we invited current and former editors, writers, community members, and workers to make new meaning from the Workshop’s archive. Together, they have awakened AAWW’s print anthologies and journals, returned to the physical spaces of the Workshop starting from our basement location on St. Mark’s, and given shape to the stories from within AAWW that circulate like rumors, drawing writers back again and again. In revisiting the Workshop’s history, we hope for insight into the ever-changing landscape of Asian diasporic literature and politics and inspiration to guide us forward in our next 30 years. Read more in our AAWW at 30 notebook here.

In late 2020, I was watching a virtual AAWW event on YouTube and smiled when I saw a drawing of the Workshop’s couch in the corner. It was the exact shade of light green that I remembered, a color a bit reminiscent of pistachios, and almost invited the viewer to come and sit down, this fixture of the live events having found its way into pandemic-era readings. It had been drawn in what seemed like an easy, effortless movement—the oversized, spacious seat and a large, plush pillow on the left-hand side—which of course meant that it had probably taken the artist a substantial amount of skill and time to get right.

Maybe it’s because my work at AAWW had officially involved office administration and event logistics, or maybe I felt some weird stake in having this “insider knowledge,” as if having the scoop on the story might prove something about the value of my work, but I immediately thought about how the couch actually has not one, but two pillows.

At the time, I hadn’t realized the drawing had been designed by Britt Gudas, who was a colleague when we both worked at AAWW and who, like so many of us who have come through the Workshop, has become a close friend. I supposed that at the time Britt drew the couch (which was likely after I left—something’s always from “after I left” or “before my time,” isn’t it?), it only had one pillow. (The furniture’s provenance itself is a story I forget the details of but one that then-ED Ken Chen recounted a lot; something about how he got a bunch of expensive Design Within Reach pieces via donation.) I loved that in the logo, Britt added a smiley face where the second pillow was supposed to be; it made so much sense to me. It was what we did in the space: brought things to life.

I worked at the Workshop from 2012 to 2016, at first for a few months as an events intern and then as a staff member. So much of what we all did there will never go on any resume, and as such, I remember spending a lot of time looking for this second pillow. I don’t remember when it was exactly that I noticed that it was gone. It was likely to have been just before some event, and maybe we made do by either centering the remaining one or taking it off the stage altogether. After some retracing of steps, I gave up. There could only be so many places I could try finding it; despite AAWW’s outsized reputation, the West 27th Street space is relatively small. (Once, a former classmate who was thinking of applying to an internship but ultimately decided to switch tracks, wrote to me that it was okay, the organization seemed like it was so big that we’d probably not even see each other.) It was just a pillow, and we didn’t have time, the show always had to go on, something new had to be taken care of, and even though I’d end up feeling really bad for not finishing some tasks—even for a while after I left the job—certain things, however random, just had to be left unaddressed. If you know, you know.

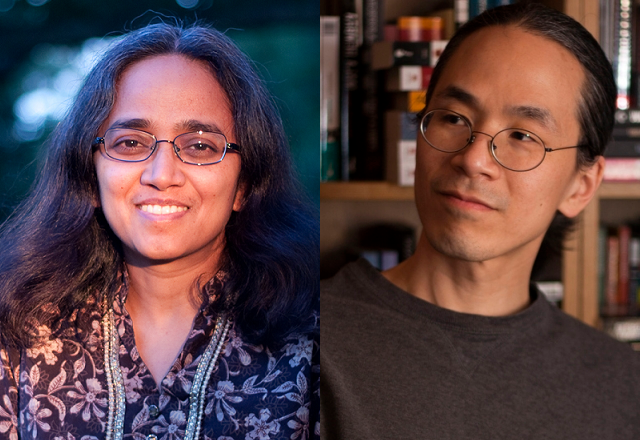

What joy, confusion, and hilarity, then, to find out that the pillow was in the adjacent office space that Ed Lin and another writer rented out as a shared writing studio. If memory serves, it was in there for a good several months at that. One of them needed to use it as a cushion for their uncomfortable office chair, though apparently it didn’t improve matters much.

As I reminisce now, I realize that if we found the pillow during my tenure there and Britt drew the couch after my tenure, then it must mean that at the very least I’d left it where I found it, or that others continued to borrow it. In the conversations that led up to my hiring as a staff member, I remember a colleague saying to me that I’d be a good steward of the space, a good caretaker of it. “Tenure” comes from the Latin “tenere,” meaning, “to hold.” The Workshop was where I first heard someone use the phrase, “to hold space.” I can’t be the sole judge of whether or not I was good at my job, but it was something I tried my very best to do there: make sure folks had what they needed.

A lot of people used the couch for comfort, especially interns: The main space of the 6th floor that morphed into audience seating in the evenings was their workspace during the day. The sofa offered a place to sit and read or talk. Other times I’d see writers in workshops stretch out on it on their stomachs during free-write time. My then-colleague Jyothi had needed one of the pillows to support her back after having slipped outside one winter.

It strikes me now that I myself rarely saw the couch that way; by its nature it invoked rest, but by design of the environment, it invoked work. I often saw it as a makeshift table on which to temporarily set down event equipment; or as a large, clunky stage prop that we had to angle a certain way to make room for a banner and projector screen; or as a way to cover some of the boxes of books that sat just behind the stage platform until I could return them to the distributor.

To me, having found a home in the space, and in turn becoming a host of it, the couch was a place for guests to sit and tell their tales during events. The raised platform on which the sofa sat literally uplifted these artists’ voices, but being on top of the stage, sitting on it was also always a little bit a part of a show—by its nature invoking one to recline, but by design of the environment, inviting them to sit up.

The spots I felt the most comfortable in, incidentally, were the margins of the venue—the edges of the stage; the long table in the back that had been fashioned by laying large wooden planks on top of a row of short black filing cabinets; leaning against the wall in the hallway with one eye on the door buzzer and another on my watch or phone, texting about camera chargers and five-minute warnings or live-tweeting inspirational quotes about how to make a writing life. Maybe when I got home I’d follow some of the advice. More likely when I got home I’d finally rest.

I’ve since worked other jobs, navigated and negotiated my time for work and rest in different ways. I’m going through the edits for this piece after the second week of a new job (a remote one, at a for-profit institution), a week during which I had to take a large chunk of time off to rest because I was sick. I felt a little guilty about it, I noticed, but not as guilty as I might have before.

Eight or nine years ago, I would’ve gone back to work after less time, chalked it up to some kind of “responsibility” or even “resilience” on my part. It would have meant I was a valuable worker. Of course, the imprudence of a decision like that has been made all too clear since the pandemic began, but it’s also true that too few of the arts nonprofit positions I’ve held or encountered ever offered paid time off. At a very deep level, it raises a question that now ultimately feels wrong for an employee to have to ask themselves: Can I afford to rest?

On three days this week, my answer to that question was “Yes.” I requested the time, turned off the computer, and moved from the sturdy chair to the softness of my bed.

When I look up the make of the Workshop sofa now, it’s listed as a sleeper sofa. I find that so interesting, especially in a time when rest and care for oneself has the potential to become something of a badge, an accomplishment to show off, seeming like an antithesis to the way Audre Lorde—many of whose words reverberated through the AAWW space in epigraphs or writing prompts—referred to it as “self-preservation.” I don’t think I ever actually unfolded the furniture to its sleeper state, but do know that Ed Lin had couch-surfed on it a few nights when Hurricane Sandy hit and AAWW offices still had power and water.

The single pillow made it yet another thing in the Workshop space that had its quirks—that cumbersome Dell(?) laptop that interns used for event tech or transferring A/V files; the piñata stick we had to use to adjust the position of the overhead projector; that hastily written email that asked me, the lone teetotaler on staff, to look into biodynamic wine for upcoming events; the old credit card machine we eventually replaced with a Square reader; the spotty Wi-Fi (oh, the Wi-Fi).

I’ve been fascinated by “institutional knowledge” of groups and organizations, especially arts nonprofits, since before I knew what it was called. In fact, I think I first heard about the term while working at the Workshop. It’s a mix of what happens when you combine vision, legacy, shoestring budgets, and mutual aid. Add to that the work of employees past, leaving a deep impression into the memory foam of this collective couch. The tips and tricks and absurd anecdotes you inherit, the lore you create, the myths you tell yourselves. Maybe sometimes they’re more important than the mission itself? And maybe engaging in their circulation and recirculation requires more labor than the job does. These are the kinds of stories you find yourself carrying: the absolutely random shit that you realize much later was holding more meaning than it needed to, that maybe you could’ve set down and dared to let rest, let be, let gather some dust before somebody else took it on. It’s like the second pillow—the couch actually turned out quite fine without it, and eventually someone found a way to fill out the “empty” space.