“It seems that reading Kim Hyesoon in English and from the United States entails a radical re-positioning of one’s reading perspective, from imperial center to the vanishing point.”

June 23, 2016

Almost a decade ago, Joyelle McSweeney came across a poem in Circumference Magazine written by South Korean poet Kim Hyesoon and translated by Don Mee Choi. McSweeney and her co-editor, Johannes Göransson, breathlessly contacted Choi to ask if she would work with them on an anthology of English translations of Kim Hyesoon’s poetry. Since then, Action Books has brought out four titles, the most recent one being Poor Love Machine, published in April 2016.

Below is a curated collection of critical essays, imitation of forms, treasury of dreams, written by a handful of poets after reading Choi’s translations. Their reactions to Kim Hyesoon’s words are vivid, ethereal, poetry in itself.

— Contributors —

i. Joyelle McSweeney / ii. Johannes Göransson / iii. Geneva Chao / iv. Carmen Giménez Smith / v. Kim Koga / vi. Jake Levine / vii. Janice Lee / viii. Ji Yoon Lee / ix. Francois Luong / x. Monica Mody / xi. Heidi Lynn Staples / xiii. Lisa A. Flowers

Joyelle McSweeney

The Radical, Collaborative Project of Translating, Publishing, Distributing, and Reading Kim Hyesoon in English

As I read the short testimonies collected in this project, I feel a thrill of recognition. Here is an array of US-based writers—from a variety of ethnic groups and ages and with a variety of immigration statuses and nationalities—who have discovered in Don Mee Choi’s English translations of Korean poet Kim Hyesoon a radical looking glass which reorients the world and recasts it in its true black light, a light opposite to capitalism’s, militarism’s, and neocolonialism’s white-lit screens. As Don Mee Choi remarks in her interview published in The Margins last year, “I was not opposed to joy; it wasn’t what I knew best.” It seems that reading Kim Hyesoon in English and from the United States entails a radical re-positioning of one’s reading perspective, from imperial center to the vanishing point. Once we readers are moved into the vanishing point, it becomes a zone; it becomes the zone of the Paridegi, Kim Hyesoon’s iconic abandoned princess who is radically de-privileged by her abandonment and radically reconfigured by her new vulnerability, her painful proximity, her hearing of lost souls. Kim Hyesoon’s poetry operates on its readers by gathering them into its own mobile and disarming zone.

Some readers who—due to their race or gender—might be expected to identify with American power find in Kim Hyesoon’s work a welcome demolition of that identification. Poet, publisher, and translator Jake Levine writes, “in order to meet the poems on their terms, I must become less American, less white—I must transgress and disappear. If we are willing to open ourselves to that inversion, an imagination that produces negation, we can understand erasure as a creative force and ‘be born as a new illness.’” On the other hand, writers with less access to the privilege of American subjecthood discover in Kim Hyesoon a strategy for revolt—and the means as well. Ji Yoon Lee describes Kim Hyesoon’s debilitated, non-human speaker as “a jarring and destabilizing force” which “manifests”.

*

But that’s only half the story, because the other half (or perhaps a second 100%) is the generosity and brilliance with which Don Mee Choi has labored to bring Kim Hyesoon’s oeuvre into English. When I first read Don Mee’s translations in Circumference Magazine nearly a decade ago, I turned to the then au courant digital media of message boards and list servs to try to track her down. Susan Schultz, poet and editor of Hawaii’s TinFish Press, finally acquainted us. Don Mee was receptive but possibly a little alarmed to hear how ardently Johannes and I, the editors of a new press, Action Books, wanted to work with her to bring a volume of her Kim Hyesoon translations to US readers. We have since brought out four titles, each featuring exciting selections of Kim’s work alongside interviews, prefaces, and essays—all translated, selected, and compiled by Don Mee Choi. In many ways, Kim Hyesoon’s body of work in English is actually a kind of double, a non-identical twin volatilely and unstably conjoined with her Korean body of work, constantly morphing in shape and tone, uncannily vivified by the double supply of artistry that runs between Kim Hyesoon and Don Mee Choi.

Since our first volume, Mommy Must be a Fountain of Feathers (2008), which was in fact proceeded by various journal and anthology publications and TinFish’s deceptively demure pink chapbook, When the Plug Comes Unplugged (2005) as well as a substantial selection in Don Mee Choi’s groundbreaking Anxiety of Words (Zephyr Press, 2006), Kim Hyesoon’s English influence has actively contaminated the zone of US poetry, finding fans across the spectrum from novice poetry students to US Poet Laureate Robert Hass. On the strength of Don Mee Choi’s translations, Kim Hyesoon has expanded her European and global readership. As a sign of her global prominence, Kim Hyesoon was invited to read with Nobel Laureates Seamus Heaney and Wole Soyinka during the Poetry Parnassus which preceded the London Olympics in 2012. On the strength of that performance, Don Mee Choi’s translations of Kim Hyesoon’s work are now available in the UK from the acclaimed imprint Bloodaxe Books.

*

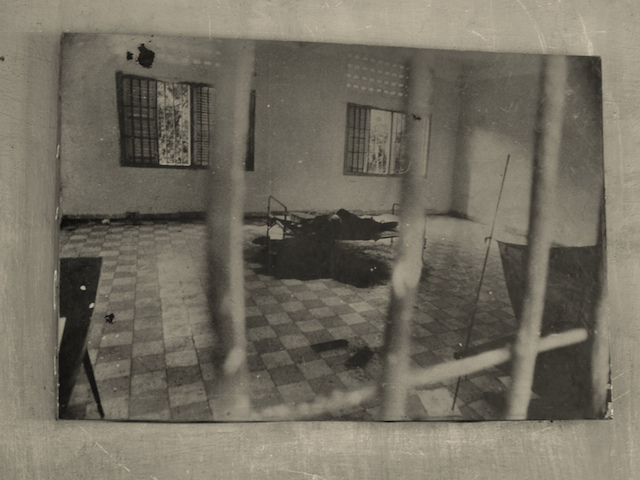

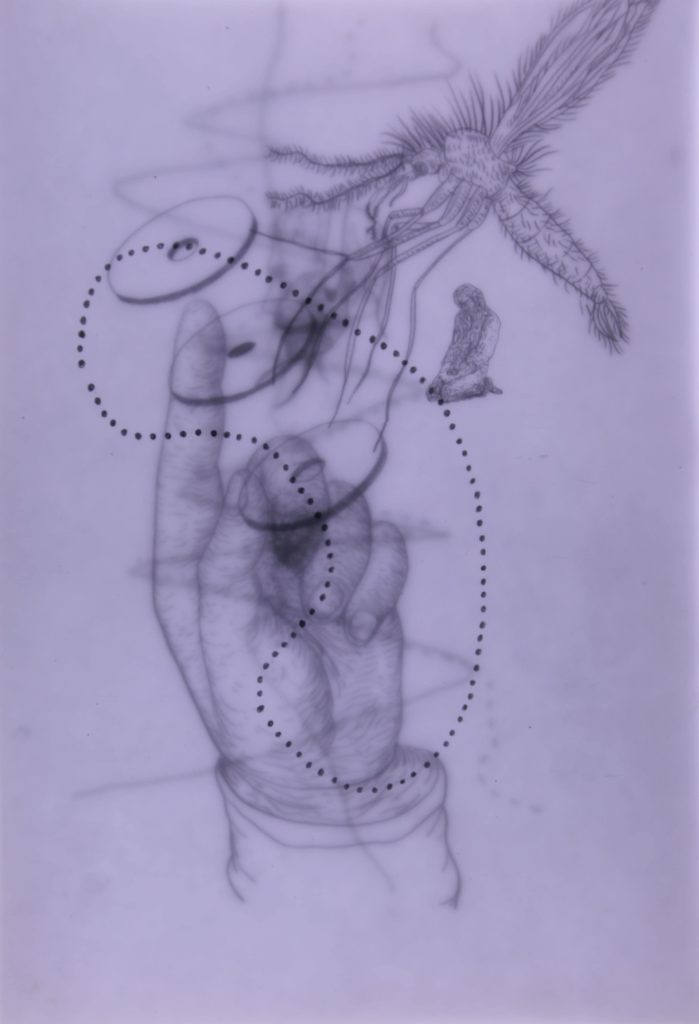

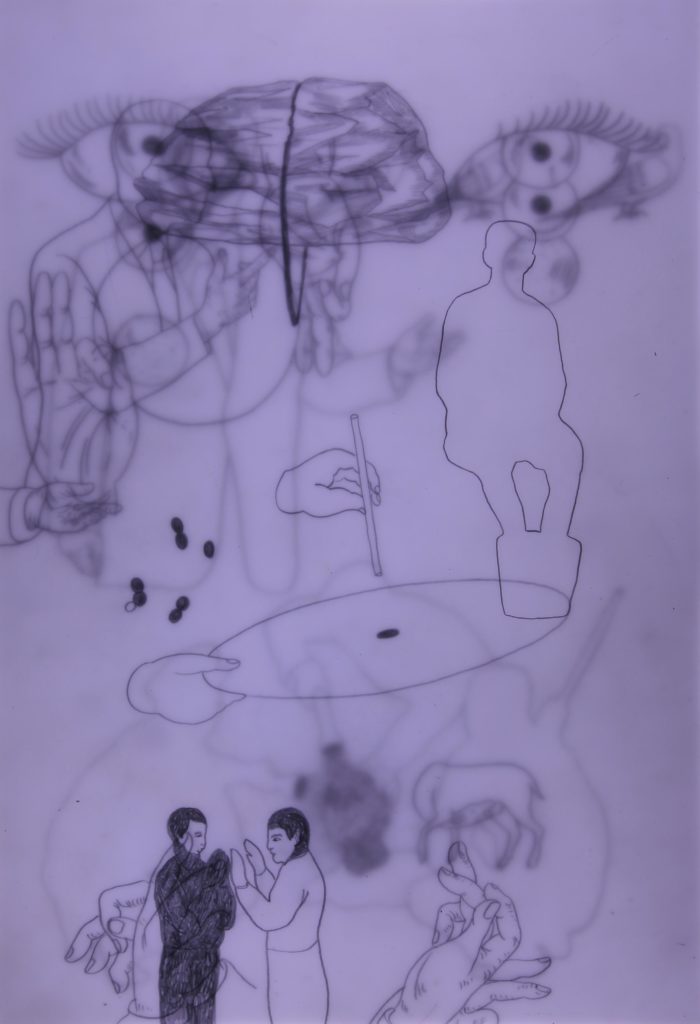

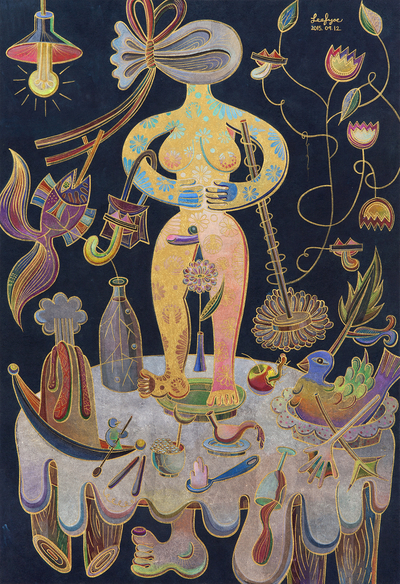

A further dimension in the dynamic collaboration among Kim Hyesoon, Don Mee Choi, and Action Books has been the books themselves as physical objects. Designers Eli Queen and Andrew Shuta have designed almost suspiciously inviting covers and layouts. Kim Hyesoon’s daughter Fi Jae Lee, an outrageously gifted artist and provocateuse who works in paint, sculpture, and performance, has graciously contributed her own protuberant and exuberant works to the covers of the second and third volumes. For me, obsession with Fi Jae Lee’s shape-shifting intelligence has formed a pliant, glittery orbital to my obsession with Kim Hyesoon. I’ve written essays and poems about this expectation-exceeding, category-confounding work. And I recently had the opportunity to visit Seoul, to drive up mountains and through tunnels I associate exclusively with the work of Kim Hyesoon, to scrutinize Fi Jae Lee’s synesthetically entropic studio, and to experience for a short time the very unique relationship that exists between these two endlessly productive geniuses, and between the women and the city itself.

Finally, the endeavor to bring Kim Hyesoon to English readers has been supported by a number of generous and committed organizations: Daesan Foundation; The Literature Translation Institute of Korea; The American Literary Translators Association (ALTA), which awarded Don Mee Choi their Lucien Stryck Asian Translation Prize; and finally the College of Arts and Letters at the University of Notre Dame, which has housed and supported Action Books for nine years. At Notre Dame a small and intrepid army of editorial assistants has cycled through the Action Books offices—poets Kim Koga, Paul Cunningham, Nichole Riggs, Zack Anderson, and Chris Muravez among them—constantly refreshing and redirecting the energies of the press.

*

This folio of essays for The Margins is a welcome chance to reflect on the resonances US-based poets experience when reading Kim Hyesoon through Don Mee Choi’s translations, and to recall that literature is not in fact the province of the individual but a zone of collaboration where it can be difficult to say where the artwork ends, or where it begins. Dislodged from the security of paternal power, Kim Hyesoon’s Princess Abandoned is a nomad, defined by the fact that she is always in transit; she forms by her motion the zone from which Art emerges. By assembling this array of voices, we hope to set in motion still more darkly radiant infernal emergencies we cannot yet apprehend. And it is our honor to be releasing at the same time as this folio a new Kim Hyesoon title in English—Poor Love Machine [Pulssanghan sarang kigye]. When this work was first published in 1997, Kim Hyesoon became the first female poet to win the prestigious Kim Su-y?ng prize for socially-engaged poetry. This major recognition, according to Don Mee Choi’s afterword, signaled a “major breakthrough and shift in the status of women’s poetry” in Korea; the parthenogenic emergence of Korean women poets in the 1980s could no longer be denied, even by a paternalistic poetry establishment. By returning to this watershed moment with the publication of Poor Love Machine in English, we hope to unleash a whole new flood of renovating, radical poetry-as-potential on new audiences, and to join it with subterranean surges and vivid upheavals already underway.

Joyelle McSweeney’s play Dead Youth, or, the Leaks won the inaugural Leslie Scalapino Prize for Innovative Women Playwrights and is forthcoming from Litmus Press in Fall 2014. McSweeney is the author of six books of poetry and prose, most of which also contain plays: Salamandrine, 8 Gothics (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2012); Percussion Grenade (Fence Books, 2012); Flet (Fence, 2008); Nylund, the Sarcographer (Tarpaulin Sky, 2007); The Commandrine (Fence, 2004); and The Red Bird (Fence, 2001). With Johannes Göransson, McSweeney founded and edits Action Books, an international press for poetry and translation.

Johannes Göransson

“What Do I Do?”: Kim Hyesoon’s Contaminated Measures

1.

Kim Hyesoon’s writing suggests a vision of the subject as constantly contaminated and contaminating, rather than stable and complete. When Ruth Williams asked her in an interview in Guernica magazine what inspired her to first write poetry, Kim replied:

In my childhood, I suffered from tuberculous pleurisy. I was brought up by my grandmother for many reasons. She was running a small bookstore in a small village near the East Sea.

As a sick kid, I always looked out the window. The objects of my observation were the sun, the seasons, the wind, crazy people, and my grandfather’s death. During my long period of observation, I felt that something like poems were filling up my body. They were in some kind of state and condition that made them difficult to render into words. As a university student, I tried hard to write them in Korean. It was at that time that I foresaw my death and the world’s death. I think my poems started at that time.

Kim entered poetry by being moved out of official culture, into a sick room—a space of isolation, of childhood—and she began to experience poetry in an altered state, when her sick and radically open body began to “fill up” with poetry—from the outside. This sense of boundaries and borders constantly overflowing is a key trope in Kim’s poetry. It’s not a liberational paradigm: the contamination doesn’t lead her to triumph over the world—instead she forsees her own death “and the world’s death”—but she is not afraid of dying, not afraid of her subjecthood being ruined or her body getting contaminated. Rather, there’s a recognition that poetry occurs exactly in the overflowing of boundaries.

2.

In her book On Longing, Susan Stewart discusses the tension between the miniature and the groteseque. The miniature—enclosed, perfect, timeless, exemplified by the dollhouse—becomes the model for a bourgeois interiority, while the grotesque—with its exaggeration and discombobulated body parts—signifies the ruination of that private space. Stewart notes

The miniature world remains perfect and uncontaminated by the grotesque as long as the absolute boundaries are maintained.. The glass eliminates the possibility of contagion, indeed of lived experience, at the same time that it maximizes the possibilities of transcendent vision.

But Stewart also recognizes that:

…the major function of the enclosed space is always to create a tension or dialectical between inside and outside, between private and public property, between the space of the subject and the space of the social.

Kim Hyesoon’s poems frequently take place in that space where the miniature world and its private space and interiority is overwhelmed, ruined by contagion or trespass, flood or sheer violence. The “social” inevitably explodes or seeps through the perfect glass wall. In the poem “Pinkbox,” the box arrives in the mail like a present:

Pinkbox that has just arrived. Pinkbox that waits to be opened. When I embrace the box, it smells of a faraway place. But no one who goes inside can escape. Ah adorable pinkbox. Pinkbox my first baby. Hello pinkbox. I want to rock pinkbox in a cradle.

The first sentence invokes that famous American anti-miniature poem, Sylvia Plath’s “Arrival of the Bee Box,” which is also ruptured by the social (invited into the box through metaphors), but while Plath’s poem moves fatally toward the inevitable liberation of the death-like sociality of the bees (slaves, a mob, etc), Kim’s poem moves back and forth in the space of the contamination. The tension of inside and outside is inherent: the enclosed miniature arrives from an outside—media punctures the speaker’s privacy even though the box itself is a perfect miniature. However, the box’s perfection is also bound for rupture. Rather than a mere dollhouse or doll, the pinkbox becomes a “baby” itself, gaining a flesh that always ruins the perfection of the miniature. Before we know it, the pinkbox has “two hidden breasts that pull on the chest painfully.” Suddenly the box is not only bodily, it’s part of the speaker’s (female, socially conditioned) body. And as soon as it has this female body, “[b]lood streamed down pinkbox,” suggesting a violence against miniature perfection. Soon enough, the speaker herself becomes the pinkbox (invoking another great poem of a miniature contaminated by the social, Paul Celan’s “Nachtstrale”): “I’ll become a boat with a pink light, foaming its way through the rainy night.” Suddenly we are out on the sea! The box may appear to be broken, but the poem repeatedly returns to the box, before concluding “It’s just dirty paper. Burn this box.”

3.

Burning or wrecking the miniature box is not the kind of liberation of the authentic, real life that American thinking tends to lend itself to; the flooding of boundaries is painful, it keeps happening. In On Longing, Stewart discusses the role of the body in attempting to make sense of the melee of the world (outside the miniature’s perfect realm):

When the body is the primary mode of perceiving scale, exaggeration must take place in relation to the balance of measurement offered as the body extend into the space of immediate experience. But paradoxically, the body itself is necessarily exaggerated as soon as we have an image of the body, an image which is a projection or objectification of the body into the world. Thus the problems in imagining the body are symptomatic of the problems in imagining the self as place, object, and agent at once.

Kim’s poetry often takes place in this vertiginous zone of the body: exploring its many shifts in scale, she explores what it is like to have a body in the world, what it is like to make art with this body in a social sphere where that body is never quite the authentic that so many romantic models of the body would have it, but where the body is always overrun with not just the social, but also necessarily distorted through the imagining of the body.

In Kim’s poetry, this sense of scale as applied to the body is constantly shifting. In “Pinkbox,” the speaker sometimes rocks the pinkbox like a baby, and other times she is inside the pinkbox, and at yet other times she is the pinkbox, but it is now large as a boat. In “White Horse,” we see these shifts happen quickly, from the very start of the poem:

What happens if a white horse suddenly enters my room? What if the horse completely fills my room? What if the horse shoves me into its huge eyeball and keeps me in there? A brightly lit train enters the horse and dark people get off. The sun fades and as the door of the deserted house of the dusk open, a dark woman clutches her torn blouse and runs out as the stars amass around her ankles…

After numerous permutations of the horse’s and the speaker’s sizes and the relationship of their bodies, we end with an impassé: “Here is my room, but I can’t enter or leave. The horse stands aimlessly in the room. What do I do?” In a large sense, the poem is the answer to that seemingly naïve question: What does one do when a white horse suddenly enters one’s private space and blows it up, setting one’s body in vertiginous experience of shifting scales? What one does is poetry.

4.

Kim’s US translator, Don Mee Choi, has stated that she think Kim’s poetry is “a poetry of translation,” rather than the standard US belief that translation is “impossible.” Choi’s translation of Kim’s work does arrive to us already contaminated by the social, but that does not mean that its force is diminished, as in so many dismissals of translations: like the pinkbox, it upends our sense of self, our imagined bodies. What does one do when Kim’s poetry suddenly enters one’s room?

One of the most satisfying things about running Action Books has been the powerful response to Kim Hyesoon’s books. The Internet is aglow with write-ups and reviews in blogs and Internet journals. Many of them seem very personal.

Olivia Cronk writes in Bookslut:

The book is absolute pleasure, though it is sometimes a pleasure of the sort you might reserve for peeing in a shower, eating liverwurst, fiddling with a hangnail. It is also the kind of pleasure related to the undetected watching of animals. It is also not unlike the excitement of realizing the self as a force for transgression.

Janice Lee writes on HTMLGiant:

Or I think of the strange dreams I have, dreams often so repulsive that I have to force myself to wake up somehow. Why is it so horrible even when I’m aware that I’m dreaming?

Allie Moreno writes:

As you make your way through, each poem is a little more delightfully terrifying and disgusting than the one before it. It’s gold. Or it’s garbage. Either way, it exemplifies what contemporary poetry should be: fresh, exciting, and unpredictable.

Sueyeun Juliette Lee writes:

The collection is indeed a cry for us to struggle against—while also dwelling and finding glory in—the minor corridors, abjected detritus, and mundanely overlooked interstices of life. In Kim’s vigorous hands, these spaces are ferocious, strange and gaspingly alive.

What all these very diverse reviews have in common is that they perceive the intensity of the writing: Kim’s poetry pulls them into a deformation zone in which the abject and the fascinating renders them radically vulnerable. Another thing they have in common is that they are on the Internet, the space that official culture fears and continually tries to discredit. But it’s in that tasteless sphere that poets from other countries or realms intermingle without the strictures of official culture. That’s Kim Hyesoon’s space: where the pigs murdered by profit-focused corporations come back to life, where the Korean war and its ensuing dictatorships come back to America, not as factual reports but as a zone which pulls us in, destroys us, puts us in touch with the dead.

Johannes Göransson is the author of six books (including the forthcoming The Sugar Book) and the translator of several books by Swedish poets, including works by Aase Berg, Johan Jönson and Henry Parland. He co-translated Cheer Up, Femme Fatale by the Korean poet Kim Yideum (Action Books, 2016). He edits Action Books and teaches at the University of Notre Dame.

Geneva Chao

Kim Hyesoon’s Sky of Guts: Occupation, Translation, Transubstantiation

Traddutore, tradditore: traduire, trahir. To translate is to betray. Our English betrays the resonance of those two words, the roundness of vowels, the alliteration. Sometimes nothing can be said that does not pass through the filter of another tongue, and another, and thus all declaration is mutation. A fish becomes a wound. A fruit becomes a severed tongue. Kim Hyesoon’s poems people the page with this mutation, grotesque not in its strangeness but in the malevolence and uncanniness of mouths, of guts, of mothers, of holes. The hole is the feminine space. This is gaping and true: feminine darkness, capacious uterus, void of sorrow, forever of water. In this generative and violent darkness Kim’s poems struggle for birth, open to receive, gag on the fleshiness of language. In the language of another colonizer, Kim’s poems are mizuko, water babies, lost children, lost mommies, caves filled with broken dolls and dead flowers, caves made “when the blue sea lets out a sigh, the sea turns inside out.”

Don Mee Choi, Kim Hyesoon’s English translator, writes of Kim’s work as itself translation, from the oral tradition of Korean women’s poetry into writing, from female identity into language. To translate translation: a game of Telephone, every motion a degree of loss. To erode form until the strawberry is meat and blood. Action is self defense; action is attack because the oppressive violence of control has spread like a smog through these poems, has translated the intangible into visceral, sky into guts. Choi asserts that South Korea is a neocolony. What are the marks of this colony?

This work assaults the eye with volleys of physicality: mouths, guts, litters, bodies. In it, the poem is a problem, a wish, a wound. The body is always present, deglamorized, stinking, bleeding, transforming, eating and being eaten. This is the effect of the neocolony: translation. This is the collateral damage of translation: betrayal. Words and bodies betray us. Space is confining or freefall. The stated rules are disingenuous, the existing powers are impotent, there is no way to unmask the unavowed power. Kim works in this maze: the seamy underbelly of consciousness grows disproportionate and filthy, the innocent becomes grotesque becomes innocent again because what, intrinsically, is more grotesque about a slab of meat than a strawberry?

In Kim’s work, there is no DMZ. It is language uttered under the eye of occupation. All stations are armed. There are only the struggles of tiny hearts and organs beating, blood flowing, and all of this sorrow and suffering, of a country, of a culture, repackaged as poem, recast as product. Heavy with nouns, her poems rain objects as thuds of meat from the sky, as colonies of swarming beasts. But woven in and out of garbage guts mouths tongues uterus cigarette butts rats babies are other nouns: love, intangible. Horizon, a thought. Dance, the gesture by which we the dark, the whiny, the unseen, the hairy, the hungry can take flight: “The hole is emitted nonstop to the outside. The mandala of rhythm floats up for a brief moment.” In this negative space: sky birthing rockets, holes birthing song, to sing a betrayal, a transgression, a redefinition, a transubstantiation itself, according to the colonial scaffold, a miracle.

Geneva Chao is a poet and translator interested in bilingualism, translation and its insufficiencies, post-colonialism and race, and sea chanteys. Her work has recently appeared in N/A and New American Writing, and she was a featured presenter at the August 2014 symposium “From Trauma to Catharsis: Peforming the Asian Avant-garde” in San Francisco. She teaches in Los Angeles.

Carmen Giménez Smith

On “Cinderella” from All the Garbage of the World, Unite!

Kim Hyesoon’s “Cinderella” highlights the tale’s sadism, the gloom fomented from the gendered and magical mutations the protagonist and her allies undergo to make her a suitable impostor in the king’s court. The poem is both icy fugue and liminal state where Cinderella is neither wife nor servant, and where her status dooms her to isolation. Although flattened by whiteness, the poem begins, in Don Mee Choi’s translation, with relatively cheery details:

Today is the day of the dancing ball

the ice bell rings from the ice palace

the ice chandelier descends like angels’ toesThe trees are surrounded by the bluestblue sparkling ice

My beloved iceman dances trapped in ice then leaves… (99)

Kim’s grotesquerie is paradoxically given life through absence—the maw of whiteness and purity—in this first-person version of Cinderella. Sterilized by ice, the poem’s landscape forebodes the emptiness of the tale-dream’s true ending and the uselessness of so much transformation in light of Cinderella’s class. As Cinderella continues to describe the scene, her world becomes “cold like the inside of a transformer”. Her self-awareness about her desperate situation quickly undoes the soft vision of the poem’s first two stanzas:

For us there is no future

only our vivid faces sealed in the ice

In our bosom the North Pole and the South Pole happily embrace

and my ice slipper falls down the steps and freezes… (100)

Ultimately thwarted by her stepmother’s “cold toenails.” Like a dream, the scene begins to fade away, and Cinderella is cast back into the dissolving carriage, which she rides back towards her enslavement:

The carriage speeds away and cries pour out like a snowstorm

Ice shoes melt, ice carriage melts

only the coachman holding a whip is left

The coachman asks, “Damn it, why won’t you stop crying?” (100)

The poem is imbued with sacrifice. Cinderella kills a rooster to offer to the kingdom, perhaps in exchange for her brief escape, but in experiencing access to the beloved, she deepens the wound of his absence and of her own miserable reality. Kim’s use of the ice serves the paradoxical purpose of representing both Cinderella’s emancipation and her exile, which works dynamically to counter the idealism of the problematic source text.

Carmen Giménez Smith recently co-edited the anthology Angels of the Americplyse: New Latin@ Writing (Counterpath, 2014). A Canto Mundo Fellow, she is the editor-in-chief of the literary journal Puerto del Sol and the publisher of Noemi Press.

Kim Koga

On All the Garbage of the World, Unite!

I don’t know what these anxieties are that plague me. But Kim Hyesoon takes me there. I am filled with holes, plagues, sadness, fluids, pinkness, phantoms, ghosts, and the anxiety of being. The ghosts that surround me are constant, successive, and unrelenting. The ghosts of geography, location—the ghosts of beings/peoples/things keep constant vigil so I am in a state of constant drowning. I’m taken to failure of flesh, the weakness/inevitability of holes. The moving dot where existence is the constancy of language and a hole that fills an I that is inconstant and mutable. The reflection of these structures/architectures color and fall pink, leafless, and so strongly situated against my life. Kim takes me to the hole that I am already in and sits on my heaving chest, pulls my string of maze thread, and cuts off my hands and feet. The limp, bloody, groping stumps take me through these anxieties and lives. And I’m again in a hole of holes, a journey of dot along a wave, inside the cat and ghost, phantom and water, Mr. Scream and Pinkbox, looking for something… looking for anything… looking…

Kim Koga is a frelance writer and editor. She is the author of Ligature Strain (Tinfish Press 2011). She lives and works in San Diego, CA.

Jake Levine

State of Absence: About Kim Hyesoon’s Popularity in America

Although Kim Hyesoon is considered to be a transformative figure in Korean literature, many Koreans are surprised when they discover the attention her work receives in America. A lot of that reaction has to do with hierarchal and institutional traditions that castrate and dominate taste-making in Korea, but also to do with Kim’s (un)conventions as a poet. I would venture to say that the majority of Koreans must imagine an American readership being interested in the type of Korean poetry indicative of traditional Koreanness—more male, more old, more translated by more male old men. Less fractal. Fewer holes. More seasons. In that vein, much criticism is written about Kim’s voice as a reaction against Korean society’s subjugation of women. Perhaps because of that friction, that history of subjugation and censure, American colonialism and patriarchy, that when I read Kim Hyesoon, in order to meet the poems on their terms, I must become less American, less white—I must transgress and disappear. This is a poetry that celebrates erasure—not of the self, but a world which oppresses and castes the self.

For instance, in the poem “Morning Greetings” she writes, “I’m a soldier of goodbye / I’m a body that produced a dead infant / I’m a minus producing machine.” If we are willing to open ourselves to that inversion, an imagination that produces negation, we can understand erasure as a creative force and “be born as a new illness.” And because most modes of oppression are built in the name of progress, it is liberating to be inside an architecture of contagion, disappearance, and of recess, when “the ghosts that have stayed up all night / drape a black cape over my poor shadow / I heard the subway station weeping in sorrow, its first train not yet arrived.” This absence, the point where Kim’s language abounds from, is not from a country, but from a state of being. This is why it is so successful abroad—because, as the Swedish poet Aase Berg says, “As garbage, love, and death accumulate in her poems, your world will be changed for real!” Because, like Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” what we share is not nostalgia for the world lost, but a hunger for a method to survive and thrive in the world in which we live.

Jake Levine is the author of 2 poetry chapbooks, The Threshold of Erasure (Spork Press 2010) and Vilna Dybbuk (Country Music 2014). A former Fulbright Scholar and currently a KGSP Scholar , he is currently working on a PhD in Comparative Literature at Seoul National University. He translated a book of poems, God/Thing (Vario Burnos 2011) by the Lithuanian concrete poet Tomas Butkus, and he is currently translating I Am A Season That Doesn’t Exist In The World by the Korean poet Kim Kyung Ju. He is from Tucson and is one of five editors at Spork Press.

Janice Lee

“Yes, poems are ways of saying you clearly remember the day of your death and your tomb. When I am writing poetry, I relive my days when a woman inside me dies many times. My body is full of graves. A sepulcher is dug up, and a young girl comes out of it with her dusty hands in tears. A lady who is a young girl and an old girl at the same time feels the presence of the young girl. I feel that the 15-year-old me and the 50-year-old me come out of the sepulcher through an illegal excavation. Time is not a straight line, but just a flat hell, like a desert. I am a tomb robber who is robbing my own tomb. Things from my tomb are exhibited under the radiant sun. Every time it happens I feel crude.”

—Kim Hyesoon in The Female Grotesque: an interview by Ruth Williams

The violence inherent in the extraction of different versions of a self becomes inevitable. A thousand lives and deaths trapped in the strange balance of a body, of the memory of a body, of the body’s absence, of the body’s ashes now scattered in the sea. I have said before that Kim Hyesoon’s books are tainted by my mother’s death. And at times, it feels that my mother’s death may be tainted by Kim Hyesoon’s poetry. Now, the most perceptibly changed landscape of death after a mother’s death, it is the ashes and rats that remain in the corners where her distinct vowels used to populate. What it feels like to read Kim Hyesoon’s poetry is to excavate the tomb of your own body. To dig deep with a well-worn shovel, to toss aside intestines and liver and fat and puss to expose the other bodies buried within our bodies. Inside, beneath the pregnant guts that spew new rat bodies, new needle pricks, tap tap tapping of rough, incessant rain, inside, there she lies, mother, waiting, remembering. Mother, dead and alive at once in the bowels of daughter, stares outwardly, blankly, like the poems that are birthed out of the same filthy, holy language, the same repulsive and affectionate words of living and disclosure and regret.

How are we haunted by poetry the same way we are by our ghosts? How do vacated spaces that become vacuums in the physical world, contract and protract within the realm of poetry to cause a reader to disconnect her own heart and head and body in the process of reading? While reading I reach for fingertips that are not there. I feel lost and scared. I feel in awe of ugliness. I feel filthy. I feel alive. I feel the size of a death in spaces. Who am I when I read this poetry? Who am I outside of the poem?

The words here are tremendous in their holiness. Let’s think of how many words overlap between those screamed in these texts and those sung inside of churches. Let’s think of how these words make us feel when we can imagine the corpses, the feeling of the corpse, that is, we don’t imagine we know what it feels to kill someone, we already know. Who here has not killed at least once? Who here doesn’t already have some bodies stacked up in their closet? Because of the killing, because of the filth, because, most of all, the loneliness, these words are utterly holy and sacred. And then, these holy words, they are clarified, understood, shattered, cannibalized, torn apart, and bunched together with other words. The words are insistent, like the 50 rats on my keyboard helping me to compose this text.

Here is what is true. Kim Hyesoon’s poems will make you think about death. You will think about the many times you have already died and were resurrected. Kim Hyesoon’s poems will make you feel then breathe. You will take a breath so deep, unlike any other breath you have taken so far. Kim Hyesoon’s poems will seem so ugly to you, so absolutely hideous and repulsive. You will then realize how natural it all is, this ugliness. You will feel at home. Kim Hyesoon’s poems will remind you of the most dead and beautiful parts of yourself. You have heard whispers in your ear, but today there is a hole in the ground and you only know how to curl up inside of it and sleep. Can I repeat myself again? I mean, if we were to rip out our intestines and forced them to talk, isn’t this exactly what they would sound like?

Janice Lee is the author of KEROTAKIS (Dog Horn Press, 2010), Daughter (Jaded Ibis, 2011), and Damnation (Penny-Ante Editions, 2013). She is Co-Editor of [out of nothing], Reviews Editor at HTMLGIANT, Editor of the new #RECURRENT Novel Series for Jaded Ibis Press, Executive Editor at Entropy, and Founder/CEO of POTG Design. She teaches at CalArts and can be found online at http://janicel.com.

Ji Yoon Lee

On Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream

I don’t think I can say it is a voice—as in the Voice which comes from a “narrator” or the “poet” or “human”—that speaks in Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream by Kim Hyesoon. Rather, the words in the poems are run by (or running away from?) a haunting structure that keeps breaking itself. Rather than delivering an image or “content” as a stable vehicle, words fall apart into scattering fragments, each turning into lurking shadows in the corner of the poems who weep, murmur, and echo. As the poems slip in and out of the body of the language-medium, rocking their bodies back and forth between binary systems and encoding themselves into tunnel-visioning numerical systems, the poetic “I” becomes a nonhuman stand-in for the constantly shifting medium/mode through which the poems operate. This “I” does not speak: alternating between absence and presence, conjuring disembodied body parts that are so palpable, only to dissipate them into thin air, this jarring and destabilizing force manifests, and it is only appropriate that, today (thanks to Don Mee Choi’s superb translation), it takes the form of a broken body that is translation, which brings out the intangible slipperiness of this ghostly “voice.”

Ji Yoon Lee received her MFA in Creative Writing from University of Notre Dame. She has two chapbooks: IMMA from Radioactive Moat Press and Funsize/Bitesize from Birds of Lace Press. Her first book is Foreigner’s Folly (Coconut Books, 2014). She co-translated Cheer Up, Femme Fatale by the Korean poet Kim Yideum (Action Books, 2016).

Francois Luong

On Rain of Mouths

“Do people know how much it hurts the darkness when you turn on the light in the middle of the night?”

—Kim Hyesoon’s “Rat,” translated by Don Mee Choi

I do not know Korean. Whatever I know about the language, its culture, or its poetry is either hyphenated or second hand. It is only fortunate that one of those hands is Don Mee Choi’s, opening the door, even so slightly. From another friend, I learned that hangul mimicked the shape of the mouth as it pronounced the syllable inscribed. Mommy Must Be A Fountain of Feather being the first book by a Korean poet I had read, I wondered about the relationship between Korean poetry and the body. A question of performativity. How complex the first sentence of “A Hen” is, all twelve lines of it in Don Mee Choi’s translation. I imagine the source text as a series of glyphs marking a choreography for the mouth. It must not look too different from Seiichi Niikuni’s seminal concrete poem, “?” (“Ame,” “Rain”). Rain of hammers, rain of rats, rain of hens, rain of hangul, rain of mouths. Hangul is neat. The poems are not. How I, and I suspect many others, saw Korean society and its poetry must not have been too different from a neo-Confucian chinoiserie. This is not so. Here is South Korea and its postmodernity, overflowing with commodities and the strangeness of the entrails of a Toshiba, a rice cooker, a kitchen, or a department store. The Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier once described the baroque as the manifestation of an élan vital seeping through the empire, the remains of the Aztecs, the ancient civilization of India, and others fusing with the architecture of their colonial masters. In Korean cinema, the tranquil landscape of a seaside town in Eo Il-Seon’s Plastic Tree, marked by prefabricated buildings and sexual violence, and the urban fluff of Kwak Jae-Young’s My Sassy Girl, that too are this élan vital. And all this too belongs to the poetry of Kim Hyesoon.

François Luong is originally from Strasbourg, France, and now lives in San Francisco. He is a poet, translator and occasional illustrator. He has translated from French the works of Esther Tellermann, Rémi Froger, François Turcot and other francophone writers. His work has appeared in LIT, Eleven Eleven, New American Writing, Verse, and elsewhere. He is currently working on a graphic poem and can be found blogging at francoisluong.tumblr.com.

Monica Mody

On Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream

Kim Hyesoon’s Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream is a companion for grief. It startles the wounds out of your own soul and you find yourself rubbing your collarbone in a spot a white bird has appeared. And rain.

The poet/translator/text/reader takes into her own body the wounds of the world or shoves her feet into the wound, small ribs break off, yet she continues to walk. The small pieces of cloth that make up the garbage quilt of this poem are never quite enough to cover us, and they are. “Are you vacant? I’m vacant.” These “dirty writings” hold the urgency of shadow, cold sweep of desolation, broken glass. How many are brave enough to stay in this room of loss outside modernity’s schedule, getting licked all night long? How many are brave enough to let these things enter them?

Kim Hyesoon brought to us via Don Mee Choi is willing to take the ice, the media of seeing into her mouth, and this lending of herself is what makes rain, water, sea, salt, so necessary to cry, this barking water that holds both our past and our future.

While you were typing

I couldn’t stop the rain

As Sobonfu Some puts it, grieving is a matter of life and death. Open to grieving and read Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream.

Monica Mody is the author of Kala Pani (1913 Press). Her poems and genre-experiments also appear in three chapbooks, and anthologies and journals including &Now Awards 2: The Best Innovative Writing, The Harper Collins Book of English Poetry, Boston Review, Eleven Eleven, PIX: A Photography Quarterly, Dusie, Postcolonial Text, Four Quarters Magazine, and Vayavya. She has been a recipient of the Sparks PrizeFellowship at the University of Notre Dame — where she completed an MFA in Creative Writing, the Zora Neale Hurston Scholarship at Naropa’s Summer Writing Program, and the Toto Funds the Arts Award for Creative Writing.

Heidi Lynn Staples

“Fill Us Up with the Outside”: Recuperating the Void in Kim Hyesoon

In my graduate course The Poem of Our Time: Garbage and Poetry at the University of Alabama, we consider the use of garbage as an imaginative and material resource for poetry. What are the poetics of garbage? What are the socio-ecological implications for demonizing waste? How might waste’s transgressive aspects prove generative? How might a new social contract inform poetic forms and processes? Our readings include Garbage by A.R. Ammons, The Wasteland by T.S. Eliot, The Garbage Eater by Brett Foster, Culture of One by Alice Notley, Malfeasance: Appropriation through Pollution by Michel Serres, and All the Garbage of the World, Unite! by Kim Hyesoon.

In Western thought, the material cosmic void is feminized and equated with the dark, excess, chaos, waste—opposite to the Abrahamic spiritual transcendent god. Kim recuperates the deprecated void into generative source, with emphasis placed on how that excessive nothing is responsible for poetic inspiration and all creation: “Hole, the heart of all things. Hole, my country, my matter, my toasty-warm god” (119). Kim Hyesoon’s work, most particularly “Manhole Humanity,” sings a song of the poet’s nonself, arises from the depths of fertile heat—that heap in which the seeming one becomes the steaming many—“I have come out of the hole, but my body is wearing a hole, the hole endlessly proliferates” (134). The void proliferates void. Avowing connectivity, “life sprouts from the fugue” (120).

Heidi Lynn Staples’ debut collection, Guess Can Gallop, was selected by Brenda Hillman as a winner of the New Issues Poetry Prize. She is author of three other collections, including Noise Event (Ahsahta, 2013), and her poetry has appeared in Best American Poetry, Chicago Review, Denver Quarterly, Ecotone, Ploughshares, Women’s Studies Quarterly and elsewhere. She teaches in the MFA program at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Lisa A. Flowers

On Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrocream

Ancestors seem to lie chipped, upon girls’ nails, all glitter and lurid crimson polish. The book appears to be narrated primarily by vivid and jaded matriarchs, some of whom have recently ascended to Ghosthood, and are adjusting to the transition much as their young granddaughters/descendants back on earth are adjusting to the onset of puberty, menstruation, etc. This book delights in constantly bashing itself open like a piñata and letting its images fly everywhere, with readers frantically scrambling to gather and savor its richly diverse candies. As in Kim Hyesoon’s previous collection, All the Garbage of the World, Unite! there is a swarm of birth activity and colors throughout. Infants come from sepia sonograms into alarming realizations of color. Souls fly out of the book in particles, embedding themselves into the reader’s eye or planting a lipsticked peelable cartoon kiss on their cheek. Scenarios play out like a snow globe of a film, flecked now and then with blood in the glass—sometimes gouts of it.

Despite all this, Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrocream is a serious, sophisticated, and blistering political and social manifesto. But, as with all of Kim’s work, reviewing it is always perilously close to being an exercise in visceral enchantment. This is both distracting (from the subtext) and perfect for it: a juxtaposition that forces us to keep paying attention. The book’s images come at us at so high a velocity that we can’t risk looking away: to drift off for even a minute is to find oneself covered in tar, menses, sequins, bone fragments, and the pureed consequences of the world’s actions: a triumph made possible not only by Kim’s brilliance but by the brilliance of her translator, Don Mee Choi, herself a stunningly original poet.

Lisa A. Flowers is a poet, critic, vocalist, the founding editor of Vulgar Marsala Press, and the author of diatomhero: religious poems. Her work has appeared in The Cortland Review, elimae, THEThe Poetry, The Collagist, Entropy, and other magazines and online journals. She is a poetry curator for Luna Luna Magazine. Raised in Los Angeles and Portland, OR, she now resides in the rugged terrain above Boulder, Colorado. Visit her here or here.

Kim Hyesoon is one of South Korea’s most influential contemporary poets. She has received numerous prestigious literary awards named after major modern poets such as Kim Su-yông, Mi-dang, and So-wôl. She lives in Seoul and teaches at the Seoul Institute of the Arts.

Don Mee Choi is the author of Hardly War (Wave Books, 2016) and The Morning News Is Exciting (Action Books, 2010), and translator of contemporary Korean women poets. She has received a Whiting Writers Award and the 2012 Lucien Stryk Translation Prize. Her other recent works include a chapbook, Petite Manifesto (Vagabond Press, 2014), and a pamphlet, Freely Frayed, ?=q, Race=Nation (Wave Books, 2014). She co-translated Cheer Up, Femme Fatale by the Korean poet Kim Yideum (Action Books, 2016). She lives in Seattle.