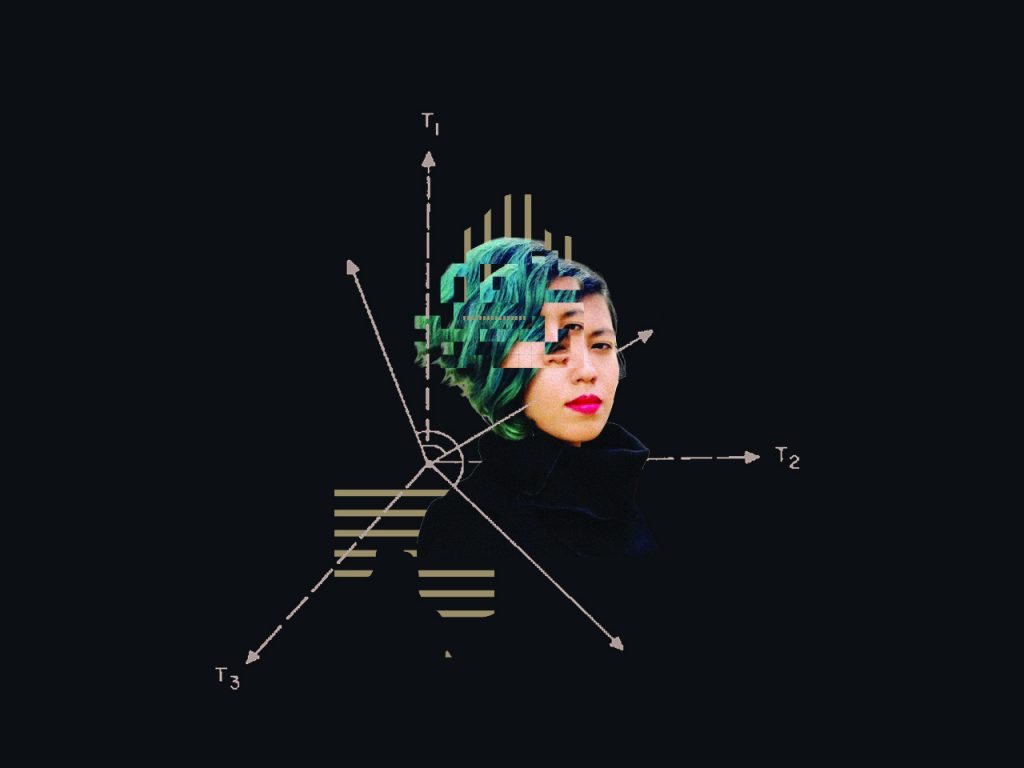

The author of An Ocean of Minutes talks the terror of time travel, immigrant fiction, and capturing grief in writing.

January 2, 2019

In Thea Lim’s debut novel An Ocean of Minutes, we meet Polly, a young woman living in Buffalo, New York in 1981. A pandemic flu spreads across the country, infecting Polly’s boyfriend, Frank. A time travel company, TimeRaiser, offers healthy people the option of traveling into the future as bonded laborers, in exchange for treatment for their loved ones. To save Frank, Polly agrees to travel to 1993 on a work visa, and they make plans to reunite in the future. But nothing goes according to plan, and Polly is thrust instead into a deeply unfamiliar country five years after her expected arrival date. The post-pandemic world of 1998 is unrelenting and terrifying, and Polly must struggle to survive—with her immigration status in jeopardy and no guarantee that her plan has worked.

An Ocean of Minutes flashes between tender romantic moments and dystopian cruelty, embedding the reader in Polly’s frantic brain as she maneuvers her way through the unknown. Thea’s rich scenes reveal a divided, oppressive society; her descriptions of abysmal living conditions and corporate control over everyday life are frightening and hit eerily close to home. In the novel, Thea asks us to imagine a world in which time travel can stop death, but also asks us what we would sacrifice for love. I spoke to Thea by phone about her love of science fiction, writing political stories, and creating community with other writers.

—Manisha Claire

Manisha Claire

An Ocean of Minutes has been called a science fiction romance. What books in the sci-fi genre did you look to as you were writing your novel?

Thea Lim

Many, many years ago I read The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin, which really got me thinking [about] how political [science fiction] can be. I think Le Guin was one of the masters of that and was always very inspirational to me. I never really thought that I could write science fiction. I was an “emerging writer” for a long time and in that time it just never felt like something that I was allowed to do. When I stumbled into it, it was very thrilling because many of the narratives that I really enjoyed—not just in text but also in TV—were sci-fi. One of the best compliments I get is when people say, “I’m a really big sci-fi fan and I was kind of skeptical about your book. But I enjoyed it!”

MC

In the novel, the America of the future is very different from our own, but it also has a familiar bureaucratic structure. How did you fit the fantastical elements of sci-fi together with the monotony of the everyday?

TL

Science fiction is interesting to me because of how much it does reveal about true life, which I think is why a lot of people like it. My background is more in writing realist fiction, so it is natural for me to try and think of it like, “Well, if you did time travel, what would it actually be like?” It might start out as one wacky inventor in his basement making a time machine, but it probably would very quickly become monetized and regulated the way any kind of travel is in our world.

I think anyone who’s ever had any experience with immigration knows that the bureaucracy becomes a character all on its own, and becomes so significant. That came from my own life experience, and I’ve had very positive and easy experiences with immigration, really, compared to a lot of other people I know. But, nonetheless, that endless filling in of the forms with the little boxes, the immense patience you have to have, the fact that the rules can change and you have no control over that, and that even the rules can change depending on who you happen to talk to—I definitely drew from all those things in order to construct that world. It was quite ironic because I had actually tried not to write something overtly political.

MC

Did you start out writing this as an immigration book or as time travel book?

TL

The book started as a time travel book. I was interested in grief and how irreversible change can be. And yet, we carry on, we just keep going and we keep managing. Grief is a very passive state and tends to be difficult to write about for that reason, and so I was trying to find a prop that could animate it in an interesting way. That’s how I came up with the idea of time travel. But, probably within the first few months of working on the book I was like, “Oh, this is about immigration.”

MC

It’s hard to imagine this as a book that was devoid of politics.

TL

All writers have crutches and in a way for me, writing things that were overtly political was a crutch. I had a lot of uncertainty about whether or not it was all right to be a writer because I had a lot of friends who were doing really meaningful work, who were social workers and immigration lawyers. I felt that it’s not enough to be a writer.

After my first book [a novella, The Same Woman] came out, I realized how you have to believe in the work. You can’t be apologizing for it. Nobody’s going to want to read it if you don’t even want to read it. I was trying to get away from being super political to validate the work, so it was a funny turn of events that it did become a political novel anyway.

I needed to find a more productive way into the politics. I think I did manage to do that. [The politics] made sense in the context of the story and I think it helps the story [that] it isn’t about me.

MC

The idea of privilege in this world is so interesting because in many instances, you see that Polly’s status gets shaped and taken away by those around her.

TL

Polly is mixed [Lebanese and white], and she was white-passing when she was in the North and in fairly good economic standing. When she’s living in the South, her economic status is much worse, and people assume that she’s not white. And I think that’s very shocking to her.

It was intentional on my part to not really show her coming to an epiphany about that, because I think that if you do have an ambiguous ethnic background there’s always an amount of uncertainty about how other people perceive you. Even if I strongly feel like something that happened to me is because someone was being racist, in the back of my head I’m thinking “am I overreacting?” or “maybe this person does not think of me as this race at all.” I always have to grapple with the boundaries of [my] racial identity.

MC

It seems to me that Polly has a hard time with relationships of many kinds. She’s suspicious of people by virtue of her circumstances, of course, but I’m wondering how you conceived of her journey in terms of how she relates to others.

TL

Even though she’s experienced loss, she’s had a pretty good life in which people behaved in ways that were predictable to her. Part of that is about privilege, where she understood the rules of the territory she lived in and was able to act within them. So, when she first arrives in the future in 1998 she expects people to just recognize that she has a right to be where she is and to allow her free movement. And when people don’t react that way, at first, she feels angry.

But there is another part of her personality that is always a little bit guarded. I do think of her as an optimist, but she doesn’t want to make a fool of herself. She doesn’t want to reveal a vulnerability that might be inappropriate. She’s the kind of person who’d probably always be worried that someone invited her to a costume party and she’d get there and nobody would be in costume.

That is partly why she fell in love with Frank, because he’s somebody who feels very much at home in any world he can conceive of. He is very warm and open, and she feels like he belongs to a warmer, brighter world. Through him, she learns how to access that world where people don’t feel lonely and afraid to warm to each other.

MC

Nostalgia plays an important role in the characters’ relationships to one another and to the company that oversees the time travel, TimeRaiser. We see how nostalgia can be manipulated and monetized. What power do you think nostalgia holds for us?

TL

We’re not good with things that aren’t in their prime. When someone dies, we have this idea that you have a certain amount of time to grieve this person. There’s obviously the first few weeks when you’re going to be really upset about this, and then maybe for a few months after. Say, three or four years on you’re still unable to get out of bed. Or, even sooner than that, like eight or nine months, if you’re unable to get out of bed, then people will think that there’s really something wrong with you, and that’s not an appropriate way to act and you’re messing with the way things are supposed to go. Culturally, we don’t have a healthy space for feeling an ongoing sense of loss.

I grew up in Singapore, where around August or September we do something called the Hungry Ghost Festival. Many other cultures have a time when everybody, together, can think of other people that they’ve lost and they do things to commemorate the fact that people have died. I think we need an outlet for that sense of loss—an outlet that is in some way public and shared.

MC

In the book, the nostalgia functions as a type of literal currency. There’s a character Polly meets, Norberto, who is hoarding all this stuff from history and hoping it will have monetary value later.

TL

When I wrote him, I was thinking about my spouse. He and his friends all still have all their baseball cards. Every time we move, I’m always asking “Should we keep these?” And he says, “Well, you never know!” That’s mostly what I was thinking on a smaller scale of monetization of nostalgia. But there definitely is a larger, more sinister corporatization of it that can be alarming.

When there’s no cultural outlet [for grief], when we’re saying that it’s not okay to continue to be sad about something that is irreversibly gone, that comes out in that interest in nostalgia. Then, of course, someone cleverly has figured out how to make money off of that need that we have.

MC

There are all sorts of things that get monetized and commercialized in the world of the novel. Feelings and vulnerabilities become a way for TimeRaiser to make money off of people, or at least take money and power away from people.

TL

We are more used to, within the realm of science fiction, the idea of an evil corporation. What I was most interested in was how much cruelty, negligence, and suffering is perpetuated by thoughtlessness, not by someone pointedly trying to deal out pain. TimeRaiser profits off of suffering, but I don’t think TimeRaiser would ever think of it that way, just as many of our corporations have all sorts of very wonderful rationale for their behavior. They see themselves as saviors. They look at it like, “All these people were sick and we found a way to get them well. All these people had no future and we found a way to solve their problems,” and they would never think of themselves as profiting off of people’s suffering.

They don’t really care about how people on the lowest rungs are treated, so they don’t put money into treating their employees well at those rungs, to liaise with those people in humane ways. In the book, if you eat in the cafeteria where Polly works, and you don’t finish your food, you have to pay for the food that’s unfinished. That detail came from a cell phone factory in China. When we hear that, it seems so dystopic but from the point of view of that company, they just want to cut down on waste.

But I do think that, generally, most cruelty in our world comes not from a desire to cause harm to other people but from a real focus on self-interest and a lack of ability to think through what those consequences are to other people.

MC

You’re not an emerging writer anymore! How did you make time to write this novel, and how do you organize your writing time more broadly?

TL

I wrote every day. I treated it like a job. The huge, tricky thing that a lot of writers have to figure out is how to work when you’re working on something that no one is anticipating, which was the case for me. I didn’t have an agent, I didn’t have an editor. The only person you’re accountable for is yourself, and sometimes “yourself” just walks back to the bed to sleep.

MC

Do you look for community with other writers?

TL

One of the greatest things that happened to me was that I did an MFA program—and by no means do I think that people have to do an MFA to become writers! But it was very transformational for me. I did my MFA at the University of Houston, and that was the first time that I ever was in the company of other writers who took it really seriously. It changed everything for me.

When I was further in the writing process, I would send drafts to my writer friends and that was incredibly helpful, though I also sent drafts to my reader friends. It’s important to have friends who are writers and friends who are readers, especially when you don’t have much recognition or much monetary reward for what you’re doing.

Then, after the book came out, knowing other writers who I could talk to was one of the most important things for me. I have good friends who had books come out this year, like Aja Gabel, who wrote The Ensemble, which came out in May, and Jessica Wilbanks, whose book When I Spoke in Tongues, came out a few weeks ago. I was lucky to meet Sharlene Teo, Clarissa Goenawan, Rachel Heng, and Kirstin Chen online, who all had books out [in 2018]. Publishing a book can be very, very psychologically challenging, so just knowing that other people were doing the same ridiculous thing as me was [so helpful].