He was nice to my father and his siblings. But still…

March 18, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following essay includes mentions of genocidal violence and torture. Please take care while reading.

Growing up, my imagination would run wild as my father would tell me about the hotel my grandfather owned in Cairo, Egypt called the Karnak Hotel. I was led to believe that one day I would stand to inherit it. To a six-year-old me, owning a hotel was such a glamorous prospect.

Being raised in a less than glamorous working-class family, I harbored romanticized notions of inheriting a hotel. Think Kevin McCallister running amok at the Plaza Hotel in “Home Alone Two: Lost In New York.”

At grade school back in Queens, all the immigrant kids would gather around the lunchroom table and try to impress one another by gloating about all the property our family owned back in our native lands. Not to be outshined, I would proudly exclaim, “Well I’m going to own a hotel that will make me a gazillionaire,” much to the envy of the other kids.

As the years went by, I would think less about the hotel, despite my childhood fantasies of owning it. Still, from time to time, it would cross my mind as more of a curiosity than anything else. I didn’t know much about it other than it has seen better days and it was nothing worth holding out for. But in a shocking turn of events in 2019, I would come to find out that my grandfather had a silent partner in the hotel venture who was none other than Aribert Heim – one of the most wanted Nazi fugitives in the world.

You see, last summer, during a family trip to Egypt, I would come to learn this family secret during the most casual of ways: over a seafood dinner at my Aunt Ranyah’s apartment in the ancient seaside city of Alexandria. In many ways, the trip was a homecoming for my father who hadn’t been back to Egypt in 34 years. Although my mother and I had been to Egypt three times before, it was the first time for my younger brother and sister to the motherland.

Besides the homecoming, Dad was also in Egypt to settle a financial dispute my grandmother was having with the other silent partners in the hotel. After my grandfather passed away in 2005, my grandmother was left to run Karnak single-handedly and it has since fallen into a severe state of disrepair.

During the dinner, my aunt and father discussed how much of a financial burden the hotel had become to the family. Even before my grandfather’s passing, it had been failing to generate a profit. To my surprise, I learned that it was far from the glamorous visions I had as a child. At the very least I thought it would be a hip, backpackers hotspot. Instead, the hotel was more like an old-school single-room occupancy hotel, catering exclusively to single Sudanese men in Egypt who provide cheap migrant labor.

As I struggled to keep up with the conversation, my father then began to discuss with my aunt one of the hotel’s former co-owners, his Uncle Tarek. My aunt then leaves the room and brings out a thick folder filled with beautifully handwritten letters and notes written in English and German belonging to Tarek. Excited with childlike enthusiasm, my dad then tells me that Uncle Tarek is actually Nazi Aribert Heim.

Seeing the look of disbelief on my face, my dad explains that he only found out that the man he called “Uncle” was actually a war criminal in hiding after The New York Times discovered in 2009 Heim was hiding in Cairo from the 1960s until his death in 1992. Apparently, my grandfather, Nagy Khafagy, had met Heim through a mutual friend and had become close friends. When it came to dealing with the autocratic Egyptian bureaucracy, my grandfather took care of anything that Heim needed.

Immediately, I had a ton of questions. Was he scary? Did you get any sense that he was evil? Were you ever suspicious of who he was? To my surprise, my father and aunt described a man that sounded quite wonderful.

“He was a very nice guy to us, nothing scary,” he said. “He was well-groomed from head to toe. He looked like a man who loved life.”

They went on to describe how charming he was when he came over. He would often bring them chocolates and buy them gifts. My father particularly remembers the tennis racquet Heim brought him as a present. They would look forward to Heim’s visits as his kindness was a stark contrast to my grandfather’s authoritarian grip on the household. The mention of his name instantly ignited a spark of joy in the room.

“Your grandfather was a tough man, but when this guy came to our house, we would get so happy,” dad told me. “For a few hours, he would take our father off our backs, and then when he left, your grandfather would be really nice to us.”

My father was most impressed with how well Heim presented himself. At nearly 7-feet tall, he was by far taller than the average Egyptian, and to say he stood out in a crowd would be an understatement. He would visit my grandfather dressed immaculately. Hiem’s personal experience affected my dad so much, growing up, my dad enforced a strict dress to impress philosophy. If he caught me wearing a sock with a hole in it, I wouldn’t hear the end of it.

“Everything about this guy was huge. He was a gigantic, athletic-looking guy who was always dressed in his best. I was impressed,” my father said.

Aunt Ranyah described how impressed she was about the air of authority he would exude. “Really, he was so confident in everything he did,” she said. “Just the way he walked made you impressed.”

Stunned by what I was hearing, I was consumed by both intense fascination as well as deep uneasiness in my stomach. Fascinated, I spent the next few days reading all I could find about Heim and became deeply disturbed by what I was to learn. Despite my family’s amicable memories of Heim, no one can deny the absolute horrors of Heim’s past that he desperately attempted to sweep into the dustbin of history.

After graduating from the University of Vienna in 1940, the newly minted doctor decided the military would be a good career move, enlisting himself in the Nazi’s most feared and notoriously brutal Waffen SS; after the war, the Nuremberg Trials considered Waffen SS as a criminal organization for its direct involvement in numerous war crimes.

Between 1941 and 1942, Heim bounced around several concentration camps throughout Europe, most notably the Buchenwald camp in Germany and Mauthausen camp in Austria. It was at these camps he would build his reputation for cruelty, which led to inmates calling him “Dr. Death”, and instilling a profound sense of fear to all those who were unlucky enough to cross his path.

Prisoners described in vivid detail the numerous experiments Heim conducted on his unsuspecting human subjects. Often, Jewish prisoners would see Heim for various ailments related to working in the hostile conditions of a forced labor camp, only to be subjected to hours of agonizing surgery without anesthesia, so Heim could observe how much pain his victims could endure, leading to hundreds of deaths.

Holocaust survivors also recount instances in which Heim would inject fluids such as gasoline into people’s hearts and remove vital organs from living victims just so he could see how long they could survive without them. In one particular macabre account, Heim was observed decapitating a victim, then keeping the skull, because it had a particularly good set of teeth, like a trophy that he used as a paperweight on his desk.

In 1945 he was captured by American troops and detained for two years but, incredibly, was released due to a clerical oversight. After the war, Heim settled in Bad Nauheim, Germany, established a gynecology practice, married into a rich family, and moved into a lavish villa. He also played in a professional ice hockey team ironically called the Red Devils. Until 1962, he lived a mostly quiet life but after a renewed interest in Germany to punish Nazi criminals, he fled, traveling through France and Spain, settling briefly in Morocco, and then finally moving to Egypt via Libya.

A few days after dinner, my father and I head out to visit my grandmother at the hotel in Cairo. On the four-hour train ride from Alexandria, all I could think about was Heim and how the hotel I always dreamed of inheriting was formally owned by a Nazi.

Arriving in Cairo I was overwhelmed by how different it was from the relative tranquility of Alexandria. Near the hotel, the crowd was as thick as motor oil. Masses of Egyptians, with their jarring energy, jostle one another for space as they make their way through the humid maze of booths hawking Chinese-made counterfeit watches and sunglasses. Personal space is a precious commodity in Souq el Ataba, Cairo’s largest shopping district.

The neighborhood is a disorienting kaleidoscope of faces. Despite arriving from New York City over a week ago, I’m completely unprepared for the sheer volume of people whose collective voices, reverberating off of the crumbling colonial-era high-rises, form an echo that could be heard for miles. Desperately, I try to stay close to my father but the flow of the crowd captures him like a rip current, carrying him deeper into the maze.

I’m stranded. Perhaps instinctively smelling my confusion, slim, skeletal men with gold teeth approach me every chance they get, attempting to lure me into their shops with the hope of securing much-needed tourist cash. But their fast-paced Cairo Arabic overwhelms my rudimentary knowledge of the language.

Suddenly, a warm familiar hand grabbed my shoulder. When I turn around, I am greeted by my father’s exhausted face. Dad hasn’t been back to Egypt since he first left in 1986. The streets he was once so familiar with have become as alien to him as it is to me.

“Stay close,” he commands, seemingly unaware that he lost me. “We should be nearby.”

Grabbing my arm, he pulls me through the maze, with the determination of a yellow-cab driver during rush hour. After several minutes we turn into a dingy, dead-end alley. Idle young men, congregate in front of doors, glare at us, seemingly aroused by the presence of a pair of lost, gullible tourists. Above one of the doorways, a weathered sign reads Karnak Hotel. I feel a knot in my stomach contort.

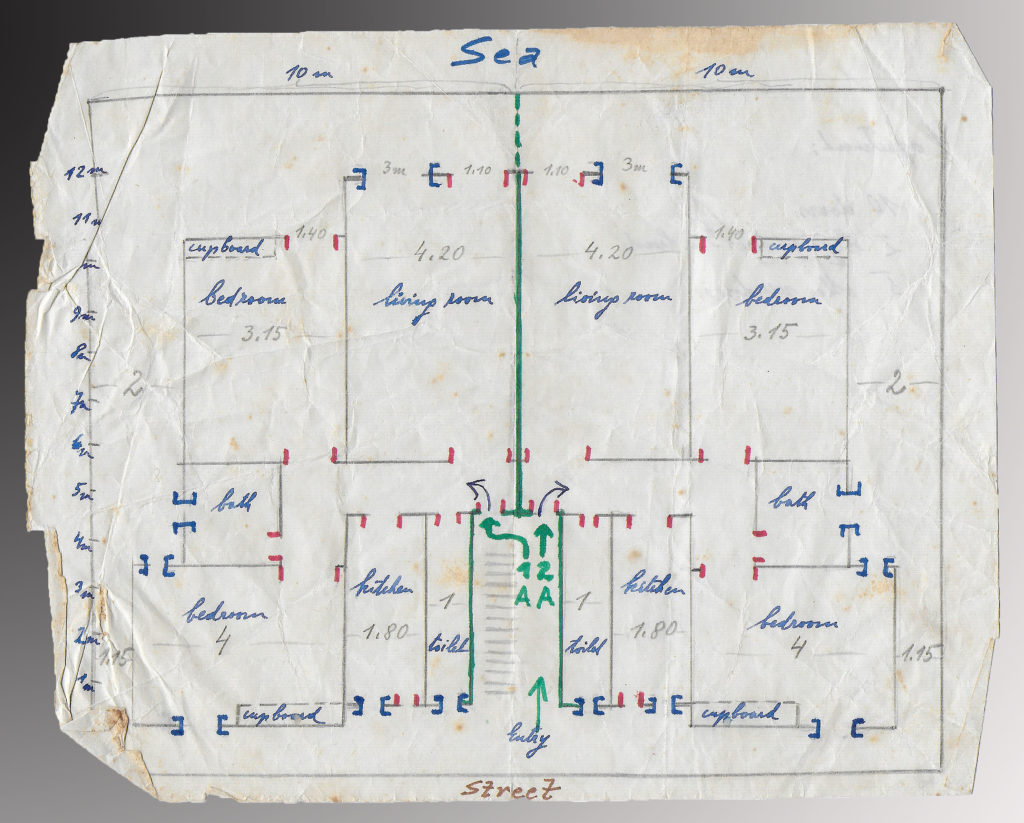

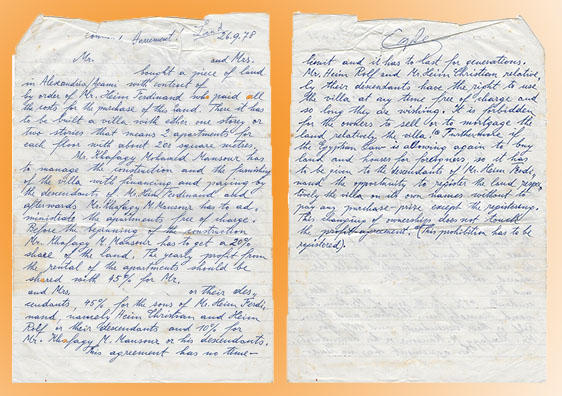

In Egypt, Heim took great pains to embrace his new home. Difficult as it may be for the physically immense German to blend, he did the best he could by converting to Islam and changing his name to Tarek Farid Hussein. Because of laws that forbid non-Egyptians from owning properties, Tarek purchased several properties in Egypt, including the Karnak, with the help of my grandfather.

In fact, according to my father, it was Heim who approached my grandfather about investing in the hotel with him. My grandfather agreed, and Heim would spend much of the remainder of his life living in the Karnak before selling his shares to my grandfather and moving to the nearby The Kasr el Madina Hotel where he would die in 1992.

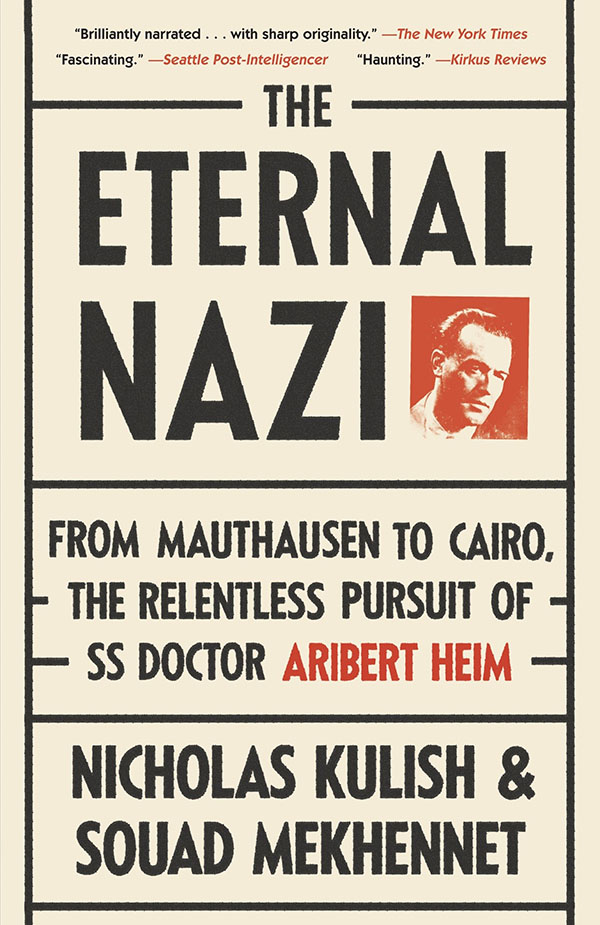

My grandfather, Nagy Khafagy, was mentioned in the book The Eternal Nazi, which chronicled the hunt for Heim. The authors, Nicholas Kulish and Souad Mekhennet, wrote:

“Herta had always done all she could to help her brother with anything he asked. When Nagy Khafagy, Heim’s Egyptian friend and business associate, needed assistance importing a Peugeot to be used as a taxi, she handled the European side of the transaction. In addition, she had always taken care of her brother’s bills, transfers of money, and taxes. Now tax officials had begun demanding either proof that she was sending the rent from the Tile-Wardenberg apartments to her brother or a payment of 10,000 deutsche marks. Given that her brother was a fugitive in hiding, he could hardly fly back to Germany, march into a courtroom, and affirm his identity.

“The family took great precautions to avoid divulging his location. Not only was mail sent to the Weil family, Herta’s friends, who handed her the plain manila envelopes, but they also used their own improvised code to identify people in correspondence. Herta was Gerda; their sister, Hilda, was Lyda. Heim was Gretl, and Friedl was Dora. On the Egyptian side, Rifat became Richard, and the suave Khafagy became the dashing Don Alfonso. The money itself was called pralines.”

The Karnak occupies the ninth and tenth floors of a decrepit building. Its elevator seems to be on its last leg, and the elevator cart is as narrow as a coffin. We take the stairs. Upon first entering the Karnak, we are greeted by a barrage of hugs and kisses from my grandmother, who has eagerly anticipated our visit. Her energy is warm and loving but I can’t help but notice the haunting Shining-like presence that the Karnak exudes.

Its walls are crumbling, and its long hallways are unlit. In the common room, a group of Sudanese men sits on worn-out sofas watching “Downton Abbey” on TV. The sight is surreal.

Desperate for air, I stick my head out of the window. To my surprise, I am greeted by a breath-taking panoramic view of Downtown Cairo. The deafening sound of thousands of shouting voices and piercing car-horns is reduced to a meditative ambient noise. As I enjoy the view, a chilling thought creeps into my mind. This must have been a view Heim had enjoyed countless times. I stare down into the pulsating crowd, uniform in its chaos, I can’t help but wonder how the hell could have Heim seamlessly hidden in plain sight for so many years without ever getting caught. Even I, who looks like any other Egyptian, draw countless stares and comments just because I carry the unshakable air of an American. After all, Israel, with all of its advanced military capabilities, lies right across the border.

Yet, in many ways, Egypt during the years Heim lived there was the perfect place for a Nazi to hide. At the time, Israel was Egypt’s mortal enemy. They had engaged in five bitter wars. When I was a kid, dad would recount the sounds of sirens blaring as Israeli planes flew overhead, forcing them to flee into underground bunkers.

During the 1950s and the 1960s, Egypt was a revolutionary place. It was the height of the anti-colonization movement and the Bandung Conference brought Egypt into the center of that movement. The handsome and charismatic Gamal Abdel Nasser promised to unify the Arab world, captivating the imagination of colonized people throughout the globe with his anti-colonial brand of Arab Nationalism and Socialism.

Culturally, Egypt experienced a renaissance in music, cinema, and literature. If the haunting voice of Umm Kulthum deeply moved the hearts of the Egyptian masses, the romantic and soulful melodies of Abdel Halim swept Egyptians off their feet. Halim’s sudden death in 1977 saw millions take to the streets in mourning and it was rumored that news of his death drove women to leap to their deaths. At the same time, writers like Naguib Mahfouz transformed Arab literature with such books as his Cairo Trilogy, ultimately winning the Arabs world’s first and only Nobel Prize in Literature.

However, with the humiliating Arab defeat in the Six Days War, resulting in Israel occupying great swaths of Egyptian and Arab territory, anti-zionism morphed into xenophobic anti-Semitism. Mass pogroms against Jews took place across the Arab world, with Egypt expelling most of its Jewish population. The fabricated anti-Semitic book “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” became required reading at public schools with my father continuing to cite it as proof of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. To this day, Holocaust denialism is widespread. Under that environment, it’s not hard to understand why Heim found Egypt an appealing place to hide.

After spending a few hours with my grandmother at the Karnak, I was ready to leave, but my father had a few more matters to take care of. As I waited, I explored the dark corridors of the hotel. Stray cats roamed the hotel as if they were long-time guests, running past me when I least expected them to. Some of the doors of the rooms were open and I could see the Sudanese men asleep in their beds. I could imagine that one of these rooms was once occupied by Heim. The thought was disturbing.

Later my grandmother would insist that we spend the night, but I begged my father to go back to Alexandra. This place that I dreamt about as a kid felt like a nightmare.

On the train ride back to Alexandria, I felt compelled to ask him what he thought of Heim, knowing fully well of what he had done, but I couldn’t spare the energy due to sheer exhaustion.

A few weeks later, we went back to New York. Months went by and rarely a day would pass where I wouldn’t think about Heim and my family’s relationship with him. How could he have deceived my family? When I ask my father now what he thinks about Heim, it’s difficult to hear. He doubts the truth.

“This man walked as if he had no sign that he did anything bad in his life,” he tells me over one of our many phone conversations on the subject. “If someone did something bad – that’s why I’m so shocked – he had no sign of it.”

I push back, reminding him that even monsters like Ted Bundy had people who loved him, but that it didn’t make his crimes any less true. I think of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust and the only Nazi to have been tried and executed in Israel. During his trial, Eichmann insisted that he was “only doing his job”.

“Maybe that’s all true and maybe it’s not,” he tells me. “All I can tell you about the man is what I knew. The man I read about was not the man that I met. The man that I met walked the streets like he wasn’t scared of anything. Anyway, he’s not alive now to defend himself.”

After our conversations, I’m still left with feelings of guilt. The idea my father has fond memories of Heim as others recoil at the very mention of his name disturbs me. It also disturbed me that I dreamed of inheriting something that he had once owned.

Then again, although it may be difficult to reconcile at first, why can’t I accept that both things could be true? Heim was a man full of contradictions. The kindness he expressed to my father was real. So were the horrors he inflicted on countless victims. Two things could be true at the same time, can’t they?