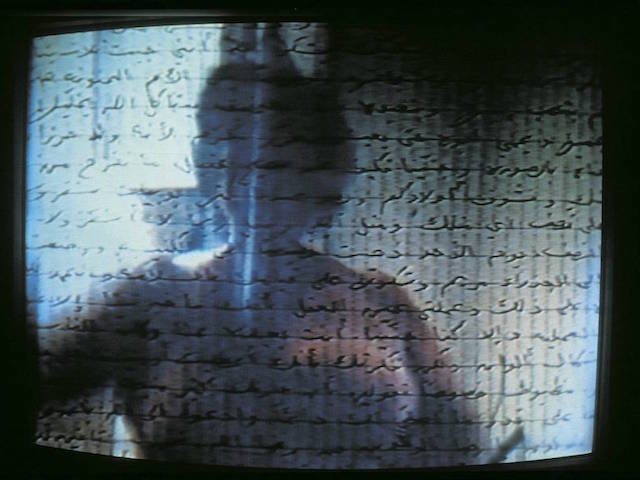

I look into the history; I circumnavigate—

This piece is part of the Wine notebook, which features original art by Su Yu-Xin.

Sandugo

noun 1. coalition; alliance

2. (historical) blood compact; possibly from Cebuano, “one blood”

In the beginning there was no land, only sky and sea, and between these two flew a great bird. One day this bird grew tired of flying, so it stirred the sea until the waters rose against the sky. To calm the sea, the sky rained down a multitude of boulders until the water no longer raged but flowed between the masses. The sky commanded the bird to leave the sea and sky in peace—to choose an island for its nest. The bird obeyed: flying down, it found its rest.

Then the sea wind and the land wind married and brought forth a child of bamboo. One day this bamboo was floating near the shore when it struck the feet of the bird, who stood on the beach. The bird became angry and pecked the bamboo violently until it cracked open. From one half of the bamboo emerged a man, Malakas, and from the other half a woman, Maganda. Then the island shook, and the earthquake called on all the fish and birds to ask what should be done with these two. It was decided they should marry. So they did, and they bore many children.

Malakas and Maganda, after some time, grew tired of having so many idle offspring. They wished to send the children away but knew of no place for them to go. The children grew more and more numerous. Their parents could have no peace. One day, in desperation, Malakas took a stick and began to beat the children left and right. The little ones fled in all directions. Some sought hidden rooms of the house, some concealed themselves inside the walls, some jumped in the earthen fireplace, and some ran far away across the island. Others still went into the sea.

Many years later, those who sought the hidden rooms became maharlika, chiefs of the islands. Those who hid themselves inside the walls became alipin, servants. Those who jumped in the fireplace became the dark-skinned Aeta and Agta peoples. And those who ran across the island became timawa, free men and women. The children who went into the sea were gone a very long time. When their descendants returned, steering great ships, their skin was white.

⁜

My memories of church are sunk in a greenish light, as though everything were underwater. Pews stained almost black, soft to the touch, the varnish worn low in the front rows, gumming up your hands, rolling into bits of tar as you rubbed your palms together. More vivid and more beautiful than the altar were two large stained glass windows near the doors, images of the Holy Spirit as a great bird—one white against panes of blue, the other flame-colored, anguished, against red. I often wondered why there were two depictions, whether one was good, the other evil. The central crucifix was life-sized, a dolorous nut-brown Christ screwed to a cross of red mosaic tile. Kind of terrifying for a kindergartener in dress uniform. Is a crucifix an effigy? I don’t see why not; it’s also a lot of exposed skin. At twelve, I try not to linger on the polished legs of the Christ, the thighs especially, which tend to merge somehow with the thighs of certain girls in class beneath their dark green plaid skirts. Amid the hum of peace, peace, peace be with you, peace, the priest breaks the bread at the altar and places a fragment of it in the chalice, saying quietly: May the mingling of this body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ bring eternal life to us who receive it. The organ breathes, lifts us into the final canto of the Mass, the lining up and shuffling forward, the snap and melt of the host, the long kneeling, then half-kneeling, then sitting. This curious hang time at the end of the Mass, everyone submerged in the aquarium light, joined in somnolence meditating, or else starting to wander back out to the world. The sacrament complete—the body of Christ within our bodies, the blood entering our blood. The priest stands to give the concluding rite. My father slips away to beat the parking lot traffic. I sense other people watching as he reaches the doors, the triple sensation of holy water, air, sunlight.

⁜

A blinding day; someone on the deck sights land. He doubts his vision. After three months and twenty days at sea, little perhaps seems real. But land it is—he alerts the captain. Three islands come steadily into view. The fleet of three ships sails toward the largest to gather provisions. But as they near, small swift boats appear, and the ships are suddenly infiltrated and robbed. The thieves make off with the captain’s personal skiff. The captain is incensed. He goes ashore with fifty men, burns dozens of houses, and kills seven people in retribution. The skiff is recovered.

The ships raise sail and continue their westward course. Ten days and three hundred leagues later, they reach an uninhabited island and make landfall. The crew spends two days recuperating. On the third day, a boat approaches bearing nine fishermen. The fishermen greet the crew joyously and offer gifts of fresh fish, bananas, coconuts, and palm wine. The captain invites them aboard his ship and gives them red caps, mirrors, combs, and ivory. Four days later, the fishermen return in boats heaped with rice, sweet oranges, more coconuts, more palm wine, and a rooster. Their lord accompanies them; his face is tattooed and he wears earrings of gold.

So, the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in Guam and the Philippines in 1521. The account comes from Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar and traveler who kept a detailed journal of the voyage. Magellan’s stated mission, as approved by the Spanish crown, was to find a trade route from Spain westward to the Spice Islands (the Maluku Islands in modern-day Indonesia). There he was to acquire a maximal tonnage of spices before returning to Spain by continuing west, thereby circumnavigating the globe. But for reasons unknown, when the expedition reached the Philippines, Magellan apparently adopted a new mission. Instead of completing the journey, he stayed in the archipelago for more than a month, traveling from island to island, Christianizing.

Why? I wonder. A genuine holy zeal? Perhaps it had something to do with the plenitude of gold he found in the Visayas, especially in the entourage of Rajah Kolambu, who ruled the Kingdom of Butuan—gold earrings and bracelets on men and women, daggers on hips with golden handles, food served on dishes of gold, gold in the very mouth of the Visayan king: three fine “spots of gold” set into each tooth. To bring these islands under the Church, and under Spanish rule, would be to subsume their riches and to glorify himself before the king and the pope.

But I also wonder about the long Pacific crossing. Sailing west from the southern tip of South America, Magellan expected to reach the Spice Islands in three or four days; neither he nor his cartographers could imagine the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. One hundred ten days at sea. What does that do to a person? The crew took in no provisions during that time. They ate biscuit powder, oxhides, sawdust, and rats. Who knows what visions Magellan experienced during that trial—what desperate prayers went up from his ships, what cries for salvation from that living purgatory escaped the mouths of those men. Perhaps the crossing transformed Magellan’s spirit. Perhaps he began to feel that he carried with him across the vast ocean the authority of his king, the Holy Roman Emperor, of God himself. And perhaps the Visayans, in their boats laden with fish and wine, seemed to him like perfect Christians, if only they were baptized.

⁜

Whatever his delusions, Magellan took pains to befriend the Visayans. Shortly after arriving, he undertook the local blood covenant, known as sandugo, with Rajah Kolambu. Pigafetta mentions this only in passing. He seems not to have witnessed the ritual firsthand. I wish he had; I want to know more. As sacraments go, none may be as primal or as strange as the blood covenant. In its simplest version, each person makes a cut on the forearm or hand, and the cuts are pressed together, sometimes bound. The oath is taken, the loyalty sworn, and the two are thenceforward consanguineous. Their blood runs in each other’s veins.

I look into the history; I circumnavigate—

In ancient tribes of the Levant, each oath-taking party would cut the forearm of the other, then drink the blood from the wound. In Syria this is known as M’âhadat ed-Dam (معاهدة الدم), the “Covenant of Blood,” and is considered one of the oldest customs of the land. Traces of the custom appear throughout the Hebrew Bible, where the verb used for the making of a covenant is karath (תרכ), “to cut.” After Abram cuts his covenant with God, shedding blood via circumcision, he becomes Abraham, or Ibrâhim al-Khalil (إبراهيم الخليل), “Abraham the Friend,” or simply Khalilullah (خليل الل), “Friend of God.” God, too, accepts an altered name, becoming the God of Abraham. The two are joined forever in name and identity; their very essence changes.

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead ( / rw nw prt m hrw), as transcribed in a coffin from the third or second millennium BC, the soul of the deceased says to the gods, “Give me your arm; I am made as ye.” The sun god Ra then cuts his arm and the deceased drinks the blood. Her soul is thereby made divine. When she comes to the gateway of light, she speaks of herself as “one who loves her arm” and is allowed to enter.

The Icelandic ritual of Fóstbræðralag begins with the making of an arch—a long strip of turf is gouged from the earth and propped overhead with a spear. The oath-takers stand beneath the arch, make the cuts, and let the blood flow into the ground, mixing it together. When they emerge, as from a shared grave, they enter a new life of fierce and unending allegiance. The gods Odin and Loki seem to be blood brothers in this manner. In the Lokasenna, when Loki is denied a seat at the gods’ feast, he says, “Remember, Othin, | in olden days / That we both our blood have mixed; / Then didst thou promise | no ale to pour, / Unless it were brought for us both.”

In parts of Central and East Africa, the practice is known as Kasendi. In addition to the joining of cut hands, small incisions are made to the stomachs, right cheeks, and foreheads. The blood from these points is collected with stalks of grass, which are then placed in separate pots of beer. Each party drinks the pot containing the blood of the other. Dr. David Livingstone was removing a tumor from the arm of a Lunda woman near the Zambezi River in 1855 when blood from one of her arteries spurted into his eye. The woman said to him, “You were a friend before; now you are a blood-relation; when you pass this way always send me word, that I may cook food for you.”

The examples are many and wide-ranging. These are but a few. What strikes me is not just the ancientness of the practice, but the ubiquity—as though the knowledge of it somehow circulates in the body. In practically all traditions, the blood pact results in a merging of life force, an interfusion of identity. The bond formed is stronger and more sacred than kinship. It guarantees a certain undying claim—to property, to nourishment, to eternal life, to whatsoever the other has.

⁜

The Catholic Mass, too, centers on a form of blood covenant, though a symbolic one without the ferric taste. The priest, lifting the chalice of wine before the congregation, says:

TAKE THIS ALL OF YOU, AND DRINK FROM IT, FOR THIS IS THE CUP

OF MY BLOOD, THE BLOOD OF THE NEW AND EVERLASTING

COVENANT, WHICH WILL BE SHED FOR YOU AND FOR ALL SO THAT

SINS MAY BE FORGIVEN. DO THIS IN MEMORY OF ME.

Here the priest lifts the chalice higher. According to the doctrine of transubstantiation, the wine in this moment becomes the actual blood of Christ—no symbolism—just as the bread becomes the actual living flesh of the fully human and fully divine Son of God. I won’t profane the doctrine with thoughts of cannibalism or vampirism. I just invite you into this mystery of faith.

The transubstantiation is a kind of climax, the holiest moment in the Mass. It’s usually accompanied by the sound of bells, a high crystalline ringing. The sound seems to come from nowhere, or from everywhere, or from God—unless you’re an altar server in middle school and ringing the bells is your responsibility. At the critical moment, as the sacrament ascends, you lift the little quadruple bell by its wrought handle and give it a lusty, wristy, sostenuto ring. As the priest’s hands come down, you let the note resound, then snuff the bells against the carpet.

Sometimes other sounds are substituted. At the Easter Sunday Mass celebrated by Magellan’s expedition on the shore of Limasawa, the transubstantiation was marked by the firing of all three ships’ artillery. The bread and wine were raised, the fuses of the cannons lit, and God spoke from the heavens. The explosions must have terrified the Visayan delegation in attendance. Some Filipinos believed thunder was the sound that came from the folds of the sky dragon’s body. Sulfur and smoke rising from the white men’s ships; there was the dragon in their midst.

After the Mass, Magellan brought a cross to the island’s summit to claim the region for Spain. No force was needed—the blood covenant, completed on Good Friday, two days prior, had already effectively rendered the territory to Spain. Enrique of Malacca, the expedition’s interpreter, enslaved by Magellan, likely explained the ritual, which he knew in Malay as casi-casi, “to be one and the same.” In the Visayas, sandugo means “one blood.” The oath-takers traditionally cut their forearms, dropped their blood into a cup of wine, and drank the mixture in turn.

The wine came from the coconut flower. Antonio Pigafetta was appropriately in awe of the coconut. He noted the way the Visayans refreshed themselves with its juice, ate its meat fresh with rice and fish, ground its dried pulp into flour, twisted its fibers into cord for their boats, and fermented and boiled and strained its contents to make vinegar and oil and milk. He estimated that a family of ten could subsist on two coconut trees for a hundred years. To make wine, the Visayans bored a hole into the unopened coconut flower and collected the sap in thick canes of bamboo fastened to the tree. The sap fermented naturally from yeasts in the air, yielding a white liquor that was sweet when fresh, bitter and strong when aged. The Visayans called the drink uraca.

I picture it cloudy, life-giving, in Kolambu’s cup. Was it the heat of the fire and moonlight on the beach that made the men start drinking? I wonder how fast they got drunk, the sand catching them as they stumbled, sending the cup around. I wonder if Kolambu, sensing something warm and amiable rising within him, stopped the revel, took Magellan by the shoulders, felt the flesh beneath the armor, and proposed the rite. How quickly did each produce his blade, his blood, as the cup was refilled? How deep the lacerations? A single symbolic drop from each, or a dram, a spill? The liquor turning pink as a shell. One of them surely drank first. One of them surely drank more. One of them drank the congealing dregs. Was the uraca fresh from the morning’s tap, and sweet? Or did it hum with the smell of iron and raw rubber, ferment in the gut. I feel it churning in my body now, I feel it pounding in my veins. Like many Filipinos, I have ancestors from Portugal and Spain. That’s my blood in the cup—

THE CUP

OF MY BLOOD BLOOD OF THE NEW AND EVERLASTING

SHED FOR YOU AND FOR ALL

DO THIS IN MEMORY OF ME