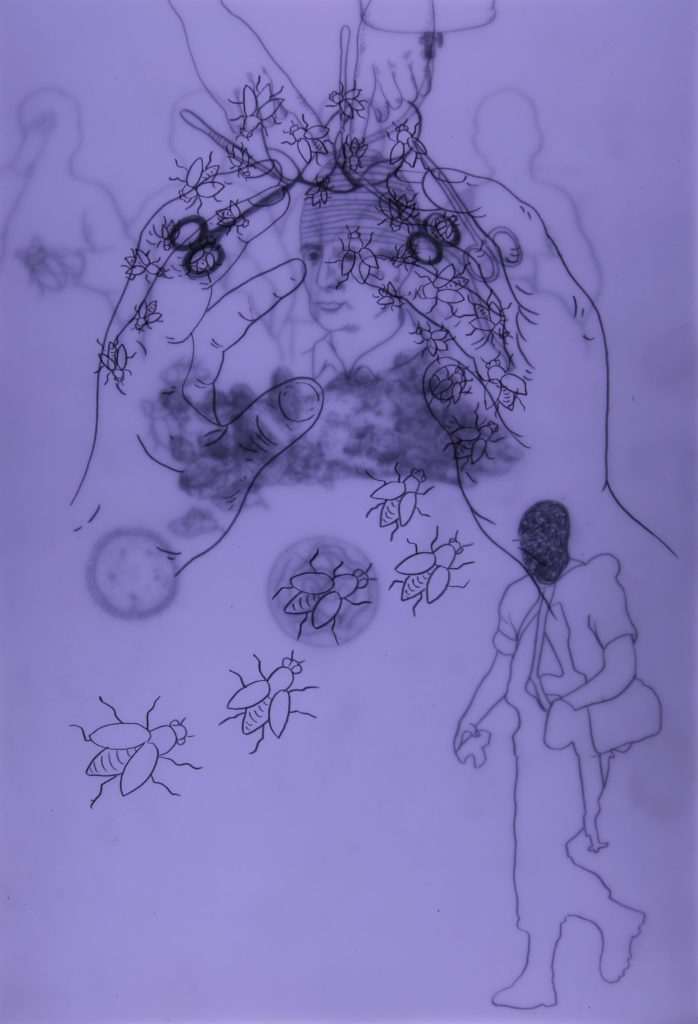

A visual counter-memory from the Alliance of South Asians Taking Action

October 22, 2021

We dedicate this article to the memories of inspiring ASATA members, social justice scholars, and dear friends Anantha Sudhakar and Birjinder Anant. We will never forget what they gave to us.

In San Francisco in 1917, the United States Justice Department indicted dozens of South Asian anticolonial activists for “conspiring to produce a mutiny to overthrow the British government in India.” These activists were members of the Ghadar Party, founded in 1913 on the West Coast of the United States. The Ghadar Party encouraged thousands of South Asian migrant workers to challenge British imperial rule across the globe and particularly in the Bay Area, in cities such as Berkeley, Sacramento, Oxnard, Stockton, and Fresno. Party members, or Ghadarites, hailed from many regions, regional, class, and caste backgrounds and they espoused working class solidarity as well as anti-war and anti-imperial commitments.1 As anticolonial political spectrums expanded, encompassing everything from protest to armed struggle, Ghadarites in North America maintained their commitment to freedom and racial equality.

At the 1917 San Francisco trial, the Justice Department presented evidence gathered jointly by United States and British officials, namely surveillance of Indian migrants collected for over a decade. Targeting Ghadarites in particular, prosecutors tapped into anti-immigrant sentiment throughout the United States in an attempt to link “aliens” (immigrants) and political radicals.2 The trials clearly reveal U.S. and British interimperial efforts to target progressive activists who challenged imperial power and built transnational solidarities by painting immigrant activists as ambiguous ‘others’ and ‘dangerous radicals.’ Moreover, prosecuting Ghadarites for conspiring to carry out a “military expedition” would set the stage for the Justice Department to prosecute activists from the 1910s through the 1970s. Following the trial, Congress passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts and the restrictive Immigrations Acts of 1917 and 1918. Decisions to remove any immigrants believed to have radical political beliefs empowered and expanded the Bureau of Investigation (today, the FBI), which became the strongest domestic intelligence agency with a specific mandate to surveil Japanese, Mexican, African American, and Indian “agitators.”

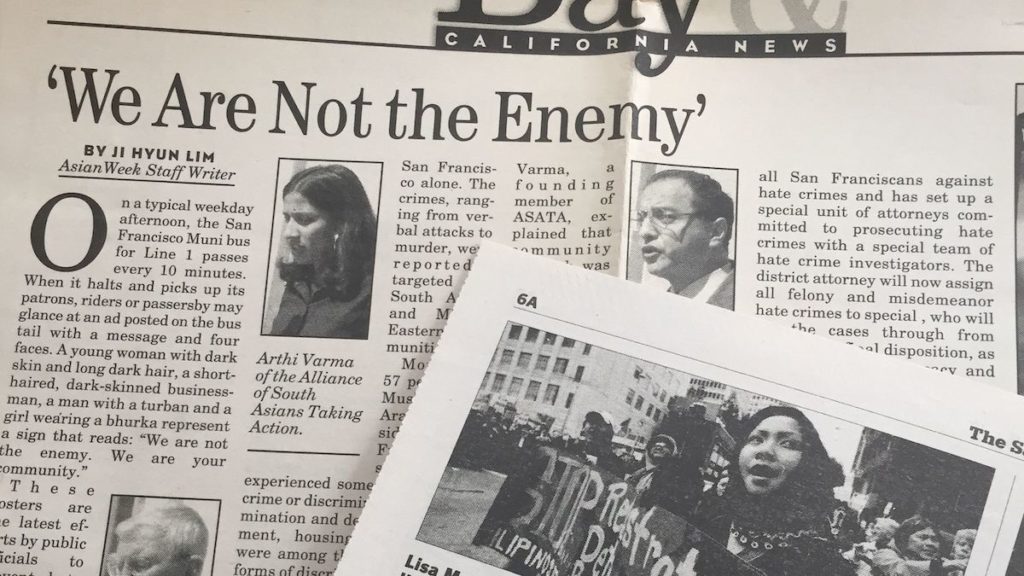

Inspired by the Ghadar Party’s rich history of radical activism, South Asian and South Asian Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area founded the Alliance of South Asians Taking Action (ASATA) in 1999 in response to a human trafficking case in Berkeley involving an upper-caste South Asian family engaged in labor exploitation and gender-based violence. At first organizing around gendered, caste, and state violence, ASATA expanded in the aftermath of September 11, maintaining its commitment to intersectional activism and broadening its left internationalist perspective.

After September 11, progressive South Asian activists in the Bay Area mobilized in solidarity with those struggling with demonization and discrimination, providing support and a sense of safety. Many Americans knew or came to realize the outpouring of jingoistic nationalism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, state targeting, and racist violence would affect the bodily and mental safety of anyone perceived as a “security threat,” an unsettling echo of the decade-long surveillance of Ghadarites in the early 20th century. The backlash was dramatically manifested in U.S. domestic and foreign policies in addition to everyday violence and discrimination, resulting in a prolonged “terror-panic” climate.3 It also launched a phase of renewed U.S. territorial empire, characterized by boots on the ground with the occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as neo-imperial warfare, including drone strikes and proxy wars in South and Central Asia and the Middle East.4 Afghans, in particular, saw the beginning of the longest war in U.S. history, whose tragic anniversary is also being marked this fall by the withdrawal of U.S. troops and the swift reemergence of the Afghan Taliban.

ASATA cofounder Anirvan Chatterjee reflects, “This was a moment for critical internal solidarities, with semi-impacted South Asians standing as ‘coconspirators’ with the most impacted communities.”

This photo essay, coauthored by ASATA members, documents the different approaches that emerged in post-9/11 organizing for South Asian Americans that laid the foundation for later activism. The campaigns we discuss here pivot broadly on two main, overlapping strands of organizing: (1) civil and immigrant rights activism, and (2) antiwar and anti-imperialist movements. Both forms of organizing have longer histories among South Asian communities in the United States than is generally known. This is not a comprehensive account, but rather a snapshot of key organizing moments representing a counter-memory to the official state archive. We hope this alternative history will be useful to activists, community members, educators, students, and media workers.

The history of the Ghadar Party illustrates how South Asian radical activism against imperial violence and racism has a long (if under discussed) history in the United States, particularly in the Bay Area. Starting a century ago and continuing today, South Asians who came to the United States as immigrants, students, laborers, and activists organized alongside leftist, anti-imperialist, and activists of color (notably Black activists) and navigated the intersections of anti-caste, anti-capitalist, antiracist, and feminist approaches.5

This organizing history is important to share, even in abridged form, given that repression of knowledge of post-9/11 experiences and state policies has led to its widespread erasure in educational curricula, within South Asian and Muslim American communities, and even in activist spaces.6 Repression is part of a strategy of imperial amnesia, a national forgetting that allows state and imperial violence to persist. We wrote this article collectively as progressive, California-based South Asian American activists and educators to challenge this deliberate forgetting, which we see in the lack of awareness among many of our students born in a post-9/11 world.

Post 9/11 Backlash: A Global View

September 11 fueled a surge of what Palestinian American scholar Steven Salaita calls “imperative patriotism,” a xenophobic and resurgent nationalist fervor that is heightened in moments of national crisis or war. The rampant suspicion of Muslims, and people perceived as Muslim, was sanctioned by the George W. Bush administration’s nationalistic framing of the War on Terror as a moral crusade in which people were either “with us or against us.” This moment was also a war on many living in the United States. White supremacists targeted turbaned Sikh American men such as Balbir Singh Sodi, who was believed to be Muslim and became one of the first victims of post-9/11 homicides on September 15, 2001.7 Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism stoked by jingoistic patriotism invoked the legacy of racial profiling that has conflated the “enemy alien” at home (a term used for Japanese and Japanese American people during World War II) with enemies abroad. Islamophobia re-emerged with Cold War-era shifts in U.S. foreign policy (particularly support for Israel) and was amplified after the Iranian Revolution and hostage crisis of 1979.

During moments of war and national crisis, racial fault lines are redrawn so new groups emerge in the bull’s-eye of white supremacy and empire. The intensified divide was that of Muslim vs non-Muslim, which deepened preexisting Islamophobia in South Asian American communities. This led some non-Muslim South Asians to distance themselves from Muslim community members in order to evade backlash. Some Indian American Hindus would wear bindis to differentiate themselves.8 This defensive racism recalled the buttons worn by some Asian Americans during World War II proclaiming, “I am not a Jap” and also shored up Hindutva sentiments (a form of Indian nationalism focused on establishing Hindu cultural, political, and social hegemony accompanied by Islamophobic, xenophobic, casteist, and sexist beliefs) in South Asian diasporic communities, further entrenching global constructions of Muslims as terrorists.

The PATRIOT Act that was rapidly ushered in by the Bush administration suspended civil rights in the name of national security for religious and national groups targeted by the counterterrorism regime. An estimated 5,000 Muslims were secretly detained and/or incarcerated in the months following 9/11. Given the secrecy surrounding these detentions, statistics were hard to come by, but some estimated that nearly 40 percent of the detainees in the first year after 9/11 were of Pakistani origin.9 As Muslim immigrant men began disappearing from their neighborhoods, fear spread in communities that saw fathers, uncles, and brothers picked up in raids and sometimes deported overseas on secret, nighttime charter flights.10

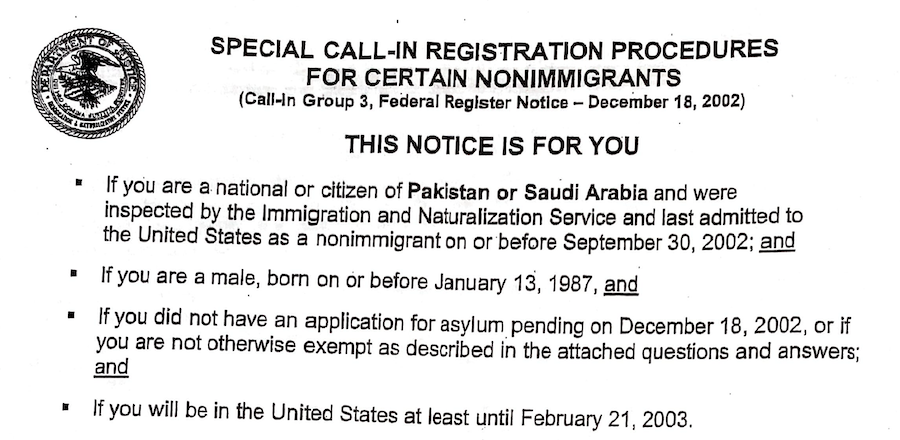

Lesser-known anti-Muslim programs, such as the National Security Entry and Exit Registration Service (NSEERS), established in 2002, enabled mass detentions and deportations.11 Euphemistically called Special Registration, the program required immigrant men between the ages of 16 and 25 years from 24 Muslim-majority countries to register at federal facilities and provide information on their social networks and mosque communities. India was actually not on the list of targeted countries for Special Registration despite its significant Muslim population, yet North Korea was included, underscoring the arbitrary underlying logic of NSEERS, which correlated with the Bush regime’s “Axis of Evil” (Iran, Syria, North Korea). This intelligence-gathering program resulted in the detention of approximately 3,000 men and the deportation of an estimated 14,000 men who had voluntarily complied.12 NSEERS continued a policy of mass incarceration, albeit without physical camps surrounded by barbed wire, as with Japanese incarceration during World War II. Notably, Japanese American activists were some of the most vocal allies of Muslim and Arab Americans, speaking out against the painful parallels between “terrorist-like” people and “enemy aliens.”

The resultant camps and secret carceral spaces were transnational, with Muslim men incarcerated in prisons such as Guántanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, as well as the less visible Bagram prison in Afghanistan. Between 2001 and 2011, activists, scholars, and lawyers began to question the legality and morality of these ghostly, off-shore U.S. interrogation sites and prisons, in addition to torture ships and internment camps. It emerged that many incarcerated people were neither “terrorists” nor “enemy combatants”—rather, they were innocent people picked up in sweeps here or handed over for bounty in Afghanistan or Pakistan. They could not provide intelligence on individuals or communities.13

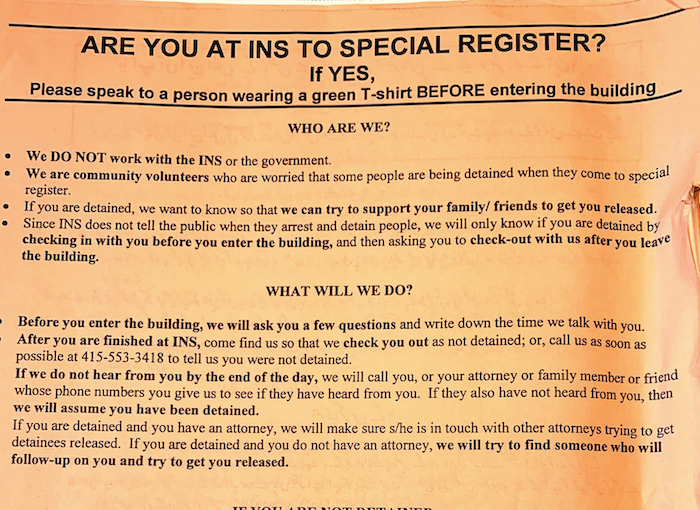

The horrifying specter of men being herded into federal facilities spurred grassroots organizing among immigrant and civil rights groups. In the Bay Area, ASATA members noted contact information of men standing outside the Department of Justice to register with NSEERS to notify their families in case they were detained or disappeared. Know Your Rights workshops provided information to community members about what to do if an FBI agent knocked on their house or mosque and if a family member was suddenly detained. ASATA members distributed multilingual Know Your Rights materials and provided legal support in collaboration with other activist groups such as the Arab American Anti-Discrimination Committee-San Francisco, National Lawyers Guild-San Francisco, Council of American Islamic Relations, and the Progressive Bengali Network. The movement that sprang up in defense of groups targeted by the surveillance-carceral state represents an important organizing moment because it provided a precedent for activism following Trump’s election, for example, non-cooperation with ICE and federal agents in the resurgent sanctuary movement of 2016-17.

Like the COINTELPRO program targeting civil rights and Black Power activists in the 1960s-70s, state surveillance succeeded in undermining collective solidarity. As suspicion and self-censorship intensified, political discussions felt dangerous and trust became increasingly precious. It is striking that even to this day, many in the general public remain unaware of “permanent surveillance,” which permeated the daily lives of Muslim Americans and furthered a racialized “surveillance divide” in U.S. society.14

ASATA members were involved in campaigns challenging racialized surveillance. For example, in 2013 the City of Oakland began planning a city-wide surveillance system called the Domain Awareness Center (DAC), comprising over 700 cameras throughout schools and public housing that used facial recognition software, automated license plate readers, and kept 300 terabytes of storage for all the data they anticipated. ASATA followed the leadership of local civil rights organizations to protest this program through direct action and engagement at city council meetings. Ultimately, the campaign was successful and the Oakland City council confined the DAC’s surveillance capabilities to only the Port of Oakland. It also prohibited the DAC’s use of facial recognition software and license plate readers. It also eliminated retention of any data. The council created an ad hoc citizens committee to draft a privacy policy that would govern the remaining components of the DAC, the first such body in the country to have this responsibility. This committee later became Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission, chaired by ASATA member Sabiha Basrai. These direct confrontations with surveillance programs are important for creating more awareness about the work of the military-spy state.

In later years, the precarity the 9/11 generation felt growing up Muslim American influenced their educational and career choices, propelling them to work in fields such as law or public policy. This shift challenged the long-standing, racially divisive stereotype of South Asian Americans as “successful” model minorities who were considered inherently upwardly mobile and politically docile. Rather, vulnerability, anxiety, and disenfranchisement, as well as opposition to U.S. state policies, led many South Asian Muslim youth to take strongly left political stances and become a new generation of leaders in social justice organizing.15 Their activism built on the political engagement of earlier generations of South Asian, Middle Eastern, and Arab American activists—a history that is only starting to be told.

New Coalitions & Internationalist Solidarities

The post-9/11 moment was significant because the redrawing of lines made “Muslim” a re-racialized category in the United States, as well as a growing site of social justice organizing around issues of civil rights, immigrant rights, incarceration, and imperialism. Activist coalitions created new labels to reflect these cross-ethnic and interracial alliances, such as AMEMSA (Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian) or MASA (Muslm, Arab, South Asian). None of these were entirely inclusive but nonetheless reflected attempts to connect the struggles of diverse groups. Importantly, new political categories laid the groundwork for later debates about uniting communities and redrawing colonial cartographies through new labels, for example, Global South.

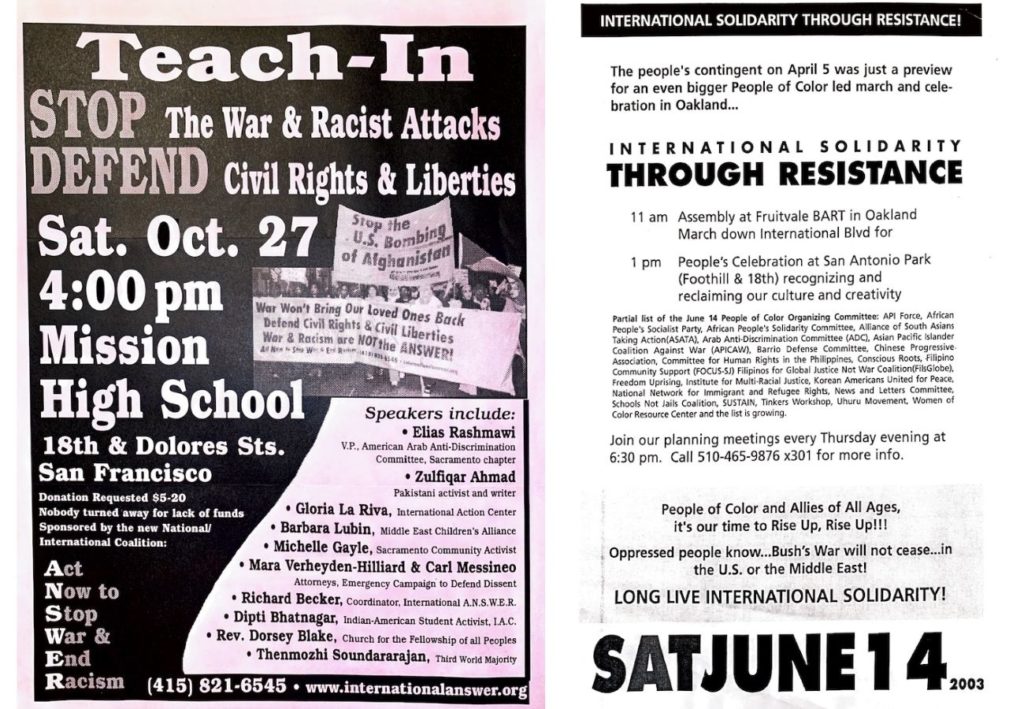

ASATA worked alongside other progressive immigrant rights, civil rights, antiwar and Palestine solidarity organizations that linked communities with shared experiences of criminalization, surveillance, incarceration, and deportation. Like many other progressive groups, it tried to meet immediate needs of vulnerable communities while standing in solidarity with other oppressed groups. After 9/11, one of the important shifts in ASATA’s work was adopting an internationalist framework of Third World solidarity, building on the legacy of anti-imperialist and anti-war movements in the Bay Area, starting with Ghadar and including movements against the Vietnam War and for Black Power. For example, ASATA participated in the Asian Pacific Islander Coalition Against the War (APICAW) based in Oakland, which was a revival of the Bay Area Coalition Against the War (BACAW) from the 1960s-1970s, and joined protests opposing U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq while calling for self-determination for peoples in the Global South.

ASATA members joined the Justice in Palestine coalition, which included an array of leftist organizations led by Palestinian activists from the Bay Area during the Second Intifada (2000-2005). Two decades later, progressive advocates of an ethnic studies curriculum for K-12 education in California have had to fight frustrating battles to include an Arab American studies curriculum that would not succumb to censorship of the Palestine question and erasure of Arab American movements by the Israel lobby and anti-Palestinian groups. ASATA members support activists and educators advocating for an ethnic studies consistent with Third World foundations of knowledge production embedded in social movements.

Current Struggles: “I have thought about 9/11 every day”

Immediately following Trump’s election, the city of Berkeley saw 14 reported incidents of hate in the first 15 days after the election, most of which were not organized by right wing groups. Berkeley local Asma Mohseni was walking with her toddler when a man began following her, screaming, “You don’t even speak English, go back to your fucking country, I’m going to kill you.” Mohseni pleaded for help, only to have a bystander yell at her and walk away. Other witnesses eventually intervened, but the man continued to yell more racial slurs, backing her up against a wall, and threatening to punch her head. Mohseni and her child escaped without injury. She describes this incident in Berkeley as the worst ethnically motivated aggression she’s ever experienced, far worse than what she faced living on the East Coast after 9/11.16 A poster campaign “Everyone is Welcome Here,” co-created by ASATA member Sabiha Basrai and artist Micah Bazant, featured a Muslim woman and accompanied a movement to officially designate Berkeley a sanctuary city.

By 2016, younger cohorts of activists in ASATA including a new generation of South Asian Muslim Americans were politicized in the post-9/11 era. In 2010, ASATA founded Bay Area Solidarity Summer, a summer camp for South Asian American youth focused on political education, organizing strategy, story-telling, and community building that built on the organizing of an earlier generation of South Asian left activists in New York. The “model minority mutiny” has subverted the “good immigrant/bad immigrant” and “good Muslim/bad Muslim” binary that plagued South Asian communities.17 Some of our college-age South Asian American students are undoing casteist, racist, and heteronormative frameworks in their own communities by recognizing their privilege, educating themselves on South Asian radical history, and supporting movements by other communities of color, such as Black Lives Matter and the Palestine solidarity movement. ASATA members have attended political education workshops on how the “Model Minority” status implicates South Asian and Muslim Americans in white supremacy, and participated in Black Lives Matter protests inspired by the activism of Asians 4 Black Lives.

ASATA is also one of several groups that has brought awareness of anti-Muslim policing and surveillance, as well as internationalist perspectives, to recent organizing against police brutality and anti-Blackness in the Bay Area. South Asian American activists have been involved in cross-racial and cross-movement solidarities, for example, by protesting the Muslim travel bans and the war on Yemen (alongside the SF Anti-War Coalition), and participating in the pivotal Stop Urban Shield campaign. Urban Shield, created by Alameda County Sheriff Gregory Ahern in 2007, was a regional, national, and global weapons expo and SWAT training that brought together law enforcement agencies from across the country and world to learn how to better repress, criminalize, and militarize. In 2014, the Stop Urban Shield campaign built upon Oakland’s rich history of organizing against policing and forced the City of Oakland to stop hosting Urban Shield.

More recently, ASATA, the Asian Law Cacus, and a diverse coalition of prison abolition and immigrant rights organizations succeeded in severing the Oakland Police Department’s partnership with the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF). Local law enforcement agencies collaborated with the JTTF to create an environment of targeted surveillance and criminalization of communities of color, especially Black, Arab, and Muslim immigrant communities.

9/11 was undoubtedly a turning point for the South Asian American community. While existing political divides and anti-Muslim sentiment deepened in some segments of South Asian America, progressive-left activists have built upon radical political histories that encompassed anti-imperialist and anti-war principles and deepened political relationships with other immigrant rights and anti-imperialist organizations. In moments of crisis, these coalitions mobilized quickly to wage and win campaigns together, resulting in a more complex political approach to left, transnational organizing that constituted joint struggles rather than simply strategic alliances. New campaigns in which ASATA has been involved have sought to understand the relationship between white supremacy, Zionism, and Hindutva, combatting the Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism undergirding Zionist-Hindutva alliances as well as transnational collaboration between US, Indian, and Israeli policing and counterterrorism regimes.

ASATA member Farah Mahesri points out that for many, 9/11 was a transformative event that launched a new era of South Asian and Muslim American leadership within communities:

I have thought about 9/11 everyday the past 20 years . . . It’s not just that my identity as an American has changed, but my identity as a Muslim has changed. To defend myself against Islamophobia, against the tsunami of backlash and hate and questions like, “Are you oppressed?” “Are your parents sorry that they had a girl?” “Are you parents okay with you being in college?” but also questions like, “How can you live in a Western country?” and “how can you support the enemy (America)?” I had to dig deep into my own history, into my own culture, my religion, my identity to its core. As a Muslim American, I have been challenged by both my identities to push to past the obvious and actually learn, to think, to understand in ways that continue to change and transform me. I learned to push past the noise and—after years—how to organize, lead, and live from a place of love and not a place of fear. That’s where I am 20 years from the day the towers fell.

Efforts to decolonize South Asian communities from casteism, racism, heteropatriarchy, homophobia, Islamophobia, class exploitation, and other forms of oppression must be coupled with efforts to dismantle global regimes that perpetuate violence, suffering, fear, and discrimination. As we reflect on the 20th anniversary of 9/11 while witnessing horrors unfold in Afghanistan as a result of the state of permanent war and ravages of U.S. imperialism, the call to share internationalist frameworks, educate new generations, combat violence and white supremacy, and build coalition-based movements remains urgent.

1 Maia Ramnth, Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire (Berkeley and Los Angeles: UC Press, 2011) and Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance, and Indian Anticolonialism in North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

2 Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveinence, and Indian Anti-Colonialism in North America, Ch 3, “Anarchy, Surveillance, and Repressing the “Hindu” Menace.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

3 TG Patel,“Surveillance, Suspicion, and Stigma: Brown Bodies in a Terror-Panic Climate,” Surveillance and Society Vol. 10 No. 3/4 (2012).

4 Shahzad Bashir and Robert Crews, Under the Drones: Modern Lives in the Afghanistan-Pakistan Borderlands (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

5 Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2011).

6 The South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) released a book called Our Stories: An Introduction to South Asian America in response to the dearth of information about South Asian Americans in K-12 education.

7 For more, see SAALT’s Post-9/11 Backlash “Acts of Hate” Database: https://saalt.org/policy-change/post-9-11-backlash/

8 Sangay Mishra, Desis Divided: The Political Life of South Asian Americans (University of Minnesota Press, 2016) and Aminah Mohammad-Arif, “The Paradox of Religion: The (re)Construction of Hindu and Muslim Identities amongst South Asian Diasporas in the United States,” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Vol. 1 (2007).

9 Stephen J. Schulhofer, The Enemy Within: Intelligence Gathering, Law Enforcement, and Civil Liberties in the Wake of September 11 (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2002).

10 David Cole, Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terror. (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2003).

11 “The NSEERS Effect: A Decade of Racial Profiling, Fear, and Secrecy.” Penn State Law Immigrant Rights Clinic (2012). Center for Immigrants’ Rights Clinic Publications. Book 11.

12 “The NSEERS Effect: A Decade of Racial Profiling, Fear, and Secrecy,” Penn State Law Immigrants’ Rights ClinicRights Working Group, 2012.

13 Anne McClintock, “Paranoid Empire: Specters from Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib,” Small Axe Vol. 13 No. 1 (2009): 50–74.

14 Sunaina Maira, “Coming of Age under Surveillance: South Asian, Arab, and Afghan American Youth and Post-9/11 Activism,” in Activists and the Surveillance State: Learning from Repression, edited by Aziz Choudry(London: Pluto Press, 2019), 79-96.

15 Sunaina Maira, The 9/11 Generation: Youth, Rights, and Solidarity in the War on Terror (New York: NYU Press, 2016). Tahseen Shams, “Successful yet Precarious: South Asian Muslim Americans, Islamophobia, and the Model Minority Myth,” Sociological Perspectives Vol. 63 No. 4 (2020): 653-669.

16 Anisha Chemmachel, Anirvan Chatterjee, and Anasuya Sengupta, “Is Everyone Welcome Here? A Poster Campaign Against Hate,” The Aerogram, 18 Deceomber 2016.

17 Alice Liou, “The Model Minority Mutiny: Whiteness is a Plague” (2018): https://aapr.hkspublications.org/2018/10/11/model-minority-mutiny-whiteness-is-a-plague/