What knowledge, beyond fluency, is required in acts of translation?

October 7, 2021

Editors’ Note: In her introduction to the Fall 2011 issue of the Asian American Literary Review, coeditor Rajini Srikanth writes of how quickly we can forget our communities’ milestone moments of political awakening. Commemorating the 10th anniversary of September 11, that issue of AALR, edited by Srikanth and Parag Rajendra Khandhar, attempted to fill in the gaps of official acts of mourning. The testimony, dialogue, essays, and art brought alive the struggles and resistance of Muslim, SWANA, and South Asian communities in the days, months, and years after September 11.

We asked a number of contributors to the Fall 2011 issue of AALR to return to their writing and speak into the space of the past 10 years. The following essay by Jennifer Hayashida is part of that series within the Living in Echo notebook. You can read Jen’s original piece from 2011 further down the page.

I thought I could organize freedom

— Björk, “Hunter”

how Scandinavian of me

—from Francis Marie Lo, A Series of Un/Natural/Disasters

something about the necessity of communicating

something about simply feeling proximity

I am in my kitchen in Stockholm. It’s August 15, 2021, and I can’t stop reloading the New York Times only to read and reread “AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT COLLAPSES,” a Black Hawk helicopter hovering above grayscaled buildings. I make the association so many others have made, to Saigon in 1975, then reload the page. This time the image depicts men with rifles protruding from car windows. I reload the page again.

Three days later, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven states, “We will never go back to 2015. Sweden will never end up there again.”

Löfven is signaling that Sweden will not again risk a rapid transformation into a multiracial and multilingual nation. In 2015, 1.3 million refugees made their way to Europe and more than 162,000 people sought asylum in Sweden from war-torn nations such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. At the time, Sweden accepted Europe’s highest number of asylum-seekers per capita, and in a speech on September 6 of that year, Löfven stated, “My Europe does not build walls, we help each other when the need is great.”

In 2015, I was still Director of the Asian American Studies Program at Hunter College, CUNY, in New York City. In looking back, my perspective shifts, in a solipsistic way, to “before”—that is, before a more mainstream understanding of anti-Asian racism and corrosive model minoritization emerged, before a firestorm erupted around the Hunter program’s institutional location and supposedly radical politics, before my contract was not renewed. In that “before,” I visited Sweden on a semi-regular basis and witnessed most of the demographic and political shifts secondhand through the media and friends. Some of my friends took in unaccompanied minors to live with them and, wittingly or not, thus became ombudsmen in the bureaucratic nightmare of pursuing permanent residency and/or citizenship.

Sweden’s generosity came to an abrupt end in November 2015 with a series of legislative measures seeking to curb and then end the flow of refugees to Sweden. Löfven stated that Sweden “simply could not do more” and needed “respite” (“andrum” in Swedish, that is, “breathing room”) from its purportedly generous stance. According to Löfven, the welfare state was full, suddenly bursting at the seams. That year, approximately 163,000 people from nations including Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Eritrea sought asylum in Sweden, of whom the vast majority were men. Seventy thousand of them were minors, and of those, approximately 35,000 were unaccompanied. Nine thousand unaccompanied minors from Afghanistan are still waiting to learn if they will be granted asylum.

In 2019, the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet produced the photo reportage “The Ones Who Came,” an important reminder that for many refugees, there is no “after,” that thousands upon thousands of refugees still live in a state of chronic anticipation and fear all across Sweden. According to the Swedish Migration Agency, all currently pending asylum and deportation cases concerning Afghan asylum-seekers are on hold due to the “crisis” there, as if the lived experience of war can be placed on hold by nation-state borders and the regulatory mechanics of passports, checkpoints, and concertina wire.

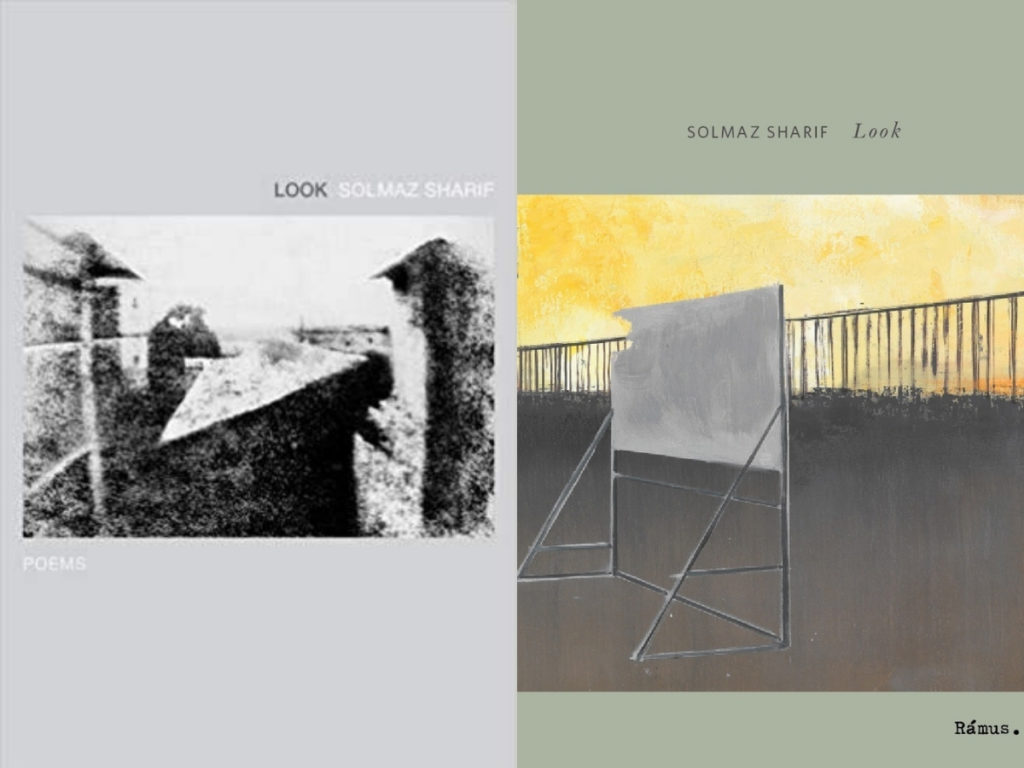

In 2016 and 2017, I co-translated Solmaz Sharif’s poetry collection Look to Swedish. I recall doing a reading with Solmaz and my co-translator, Ida Börjel, in the southern city of Malmö, one of Sweden’s most racially diverse and multilingual cities (more so than Stockholm, for example, which ranks as one of Europe’s most segregated). I remember passing a grocery store where an elderly white Swede stood outside holding a handwritten sign—ballpoint pen in careful script on ruled notebook paper, slipped into a plastic sleeve, and mounted on a slim stick—stating “No Sharia Law in Malmö.”

Through these scenes of encounter between “the refugee” and the Swedish welfare state, which I read against what Mimi Thi Nguyen terms “the gift of freedom,” I feel the need to resituate my original reflection for the Asian American Literary Review’s Fall 2011 issue. I feel an urgency to extend its scope across time and geography to encompass the impact of 2015—and now 2021—on the image of “the refugee,” how disparate refugee experiences and communities come together, and are allowed to diverge, via the intellectual and political work of Asian America.

This shift also speaks directly to my own move to Sweden in the fall of 2018, when I entered a PhD program in artistic research to pursue a project that synthesizes theory and methods from Asian American studies with translation as an artistic, performative, and political practice. Within the context of this project, I have thought a great deal about the crucial alignments, solidarities, and deviations between Asian American epistemologies and the experiences of refugees in Sweden in the aftermath of 2015. And so I feel more strongly than ever that translation needs to become a central question when we consider the transnational reach of Asian American literature and scholarship, not to reinforce a U.S. imperial gaze or order, but so that the echoes of forced displacement are made visible across and between histories, nation-states, and languages.

There is no Swedish translation for “War on Terror,” much like there is no Swedish translation for “Black Lives Matter.” The largest Asian populations in Sweden have their origins in Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan. The majority of Asians in Sweden are, in short, brown and have arrived within the past 10 to 40 years, and the vast majority were displaced as the direct and indirect result of the forever wars pre- and post-9/11. And yet, language that regulates post-9/11 racialization here remains anchored in anglophone linguistic and political regimes.

The absence of a Swedish translation for “War on Terror” or BLM does not mean that those frameworks are irrelevant here—to the contrary, Islamophobia and anti-Black racism drive far-right populist politics. U.S.–style “law and order” has become a central issue for Swedish voters, with calls for greater surveillance and policing of “kriminella,” a racialized euphemism for brown and Black people purportedly contaminating and depleting the welfare state. The Sweden Democrats, a far-right nationalist party with roots in 1980s neo-Nazi movements, could form a majority coalition with the ostensibly center-right parties Moderaterna (“the Moderates”), the Liberal Party, and the Christian Democrats in next year’s election.

Such an absence of translation speaks to the failure of Swedes, and many white Swedes in particular, to recognize in their own language their country’s particular racist ideologies and structures.

A central predicament for me in my research is to insist on the relevance of an Asian American studies intellectual framework while also taking into account the hazards of thereby imposing a U.S.–centric logic upon a northern European context. The relative absence of Asian American literature and scholarship in translation—in Swedish as well as in languages such as Arabic or Farsi—illustrates that predicament. When I ask students to read Lisa Lowe, Vijay Prashad, or Ronak K. Kapadia, I must also ask them to enter into an American academic English which, although applicable here, still situates the analyses there. All the while, many of the experiences chronicled and analyzed in Asian American literature and scholarship have a geopolitical kinship with the lives of refugees in Sweden, making translation a mechanism of solidarity rather than mere transfer.

I am currently teaching a creative writing course at HDK-Valand, the art school at Gothenburg University where I am working on my PhD, and the central question of the course is how to write across/between/through Swedish and Arabic. The here and there of the course thus becomes Sweden and locations including Syria, Yemen, Morocco, and Iraq. The course was developed by Syrian refugee and writer Khaled Alesmael and the Swedish poet and translator Jenny Tunedal, whom I have replaced. The students are for the most part newcomers, and just as there are many forms of Swedish in the group, there are a range of emotional, political, and aesthetic relationships to Arabic. Some students want to write primarily in Arabic, others in Swedish, and yet others aspire to write between or across the two—that is, to incorporate both into their projects.

Fortunately, I can borrow from friends’ in-progress Swedish translation of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée as well as my own co-translation of Look or Francis Marie Lo’s A Series of Un/Natural|Disasters—texts which all work with forms of what I (via Ronak K. Kapadia, Fred Moten, and la paperson, among others) would term insurgent, or fugitive, translation. Translation, here, becomes a method to deploy in opposition to linguistic regimes seeking to police the lived experiences of people of color and circumscribe, or fix, what constitutes knowledge. If the translator’s loyalty is akin to the loyalty of the citizen, what kind of translations can emerge from a disloyal, or insurgent, translator? If the translator-subject is also a refugee, what forms of knowledge can be mobilized in the act of translation—experiences and methods that antagonize liberal notions of borderlessness, fluency, or the purported generosity of Europe and North America? The teaching I do in this course, as well as in other artistic and pedagogical projects originating in my research, seeks to question the expertise of the translator who is fluent but has limited experience of forced displacement/liminality—the translator as missionary or anthropologist. It seeks to develop methods whereby the fugitive or insurgent translator can, together with others, mobilize her knowledge and experience—her “broken” Swedish—via a practice of insurgent translation. Here, perhaps, mutual aid as enacted in Francis Marie Lo’s A Series of Un/Natural/Disasters is a more useful model for the kind of linguistic resource-sharing and interventionist methodologies I have in mind.

In addition to presenting insurgent translation as a method by which students can both deploy and sabotage the languages that seek to regulate them, the course also proposes translation as a method for comparative analyses around experiences of war, displacement, and loss, as well as encounters with racist and xenophobic states and societies. Students in this course will translate—into Swedish, perhaps, or Arabic—excerpts from Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do and lê thi diem thúy’s The Gangster We Are All Looking For, in the hope that translation can provide a framework for considering political and literary solidarities. In a peculiar twist, Khaled recently participated in an online writing workshop through the Queens Library in New York, and I was struck by the strange but completely logical movement of incorporating Queens as a shared point of reference, that we of course should translate Bushra Rehman’s Corona. A key aspect of the course is that a “professional” translator not be part of the effort, that regimes of expertise be centered around collective experience and understanding rather than linguistic mastery.

This past August, Stefan Löfven announced that he will step down as leader of the Social Democratic party and as Prime Minister in November. Assuming that the new party leader will be accepted by parliament as prime minister, the Social Democrats will remain in power until next year’s national election. If that election were to be held today, polling indicates that the conservative block may win by a slim, but not slim enough, margin.

In March of last year, Jimmie Åkesson, leader of the Sweden Democrats, traveled to the border between Turkey and Greece, following Turkey’s Prime Minister Erdogan’s decision to open that nation’s borders to Europe, with a subsequent influx of refugees seeking to enter the EU. Åkesson roamed the crowds, distributing flyers that read, in English, “Sweden is full. Don’t come to us! We can’t give you more money or provide any housing. Sorry about this message.” I am reminded of the 1920s photo I’ve often used in my teaching, of a white woman standing beneath a banner on a porch in Los Angeles that reads, “JAPS KEEP MOVING – THIS IS A WHITE MAN’S NEIGHBORHOOD.” Students often assume this image originates in WWII anti-Japanese propaganda, whereas it actually reflects the normalized nativism 20 years earlier.

As I wrote in 2011, an Asian American studies classroom often asks that students see the arc between 1882, 9066, and 9/11, but we must also remember to extend that arc to non-U.S. borders, languages beyond English, other chronologies of “after.” After 2015 and now 2021, I will ask my Arabic-speaking students here in Sweden to translate that banner, and perhaps even Executive Order 9066. We will translate them into Arabic and Swedish, and we will see what knowledge, beyond fluency, is required in those acts of translation.

The following short reflection by Jennifer Hayashida was originally published in the Fall 2011 issue of the Asian American Literary Review, dedicated to commemorating the 10th anniversary of September 11.

From “Forum | On the Desi America-Asian America Split and New Alignments Between South Asian, Arab, Middle Eastern, and Muslim Americans”

The classroom is inevitably the space where I consider how Asian America is shifting and how I can respond to those shifts as an educator, artist, and writer. My initial move from the Bay Area to New York made me especially aware of the transmutations within conceptions of what was “Asian” and “American” about Asian America in the popular imaginary and then in particular as they were manifest among the students I worked with at CUNY.

My foundation in Asian American studies took shape in West Coast classrooms and was initially out of step with the students I encountered as an educator at CUNY. Coming from UC institutions where pan-Asian solidarity was more or less the norm, I was unprepared for the markedly uneven terrain where students identified primarily based on country of origin, language spoken, or, in some cases, whether they had attended Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech, or Stuyvesant. Those early firsthand encounters with young Asian immigrants—whom I would most likely have considered “Asian American” had I been in Oakland or Sacramento—were decisive in reframing my understanding of how Asian America cannot be rendered in relation to its West Coast center, but must be considered as a geographically and temporally specific phenomenon perpetually in flux. There was of course already significant excellent scholarship to this effect, but it wasn’t until I worked with Asian (American) students who seemed to feel that “Asian American” meant “American”—fluent in English, middle-class, with parents who stood out not for their race but for their profession—that I fully grasped the scope and complexity of the variance in that term.

Today, this particular slippage is less of an issue in my pedagogical practice, and I am instead increasingly aware of how rapidly notions of identity formation and belonging are changing on the ground, i.e. in the lives of the mostly 18-to-25-year-olds I have conversations with a few times a week. What I initially perceived to be geographic and historical particularities within a still-important political category of “Asian America” now seem to be subsumed by a broader movement towards a postracial humanism understood in the language of global capitalism, with resultant opportunities for individual self-determination. That identity is invented, not imposed, seems to be the general sentiment, and it is against this belief system that post-9/11 detention and deportation—or, as students frequently refer to it: racial profiling (eliding, for the most part, the subsequent juridical violence)—becomes a tough pill to swallow. As it should be.

For as much as the political history of Asian Americans points to longstanding and continuously resurfacing currents of foreigner racialization and exclusion/incarceration, contemporary ambivalence about how Asian Americans are marked as a racialized group (model minority still, or simply hard-working “immigrants”) makes Asian American experience a complicated framework for examining the decade since 9/11. Don’t get me wrong: students see correlations between 1882, 9066, and 9/11; the problem is that they are reluctant to make meaning of that arc and instead want to read race as archaic and exclusion as exceptional.¹ Some of them already seem to feel that West Asia is a dubious concept—few have heard of “wars in West Asia” or “dependence on West Asian oil”—and that Arab or Muslim Americans are shoehorned into the category of Asian America. They see the broader impact on South Asian Americans, yet this is frequently understood, again, as racial profiling with the implication that it is, as in a detective novel, a case of mistaken identity. Add to that the sense of an Asian American studies framework somehow making special accommodations for a marginalized group, despite the logic of such inclusion and solidarity, and I have to work even harder to emphasize that what we are looking at is not extraordinary at all.

As an educator, this is of course the work I want to be doing, but what I am hoping to emphasize here is the challenge of negotiating the rapidly changing terrain of the classroom when it comes to illustrating the presence of a racialized margin and center. One of the consequences of postracial discourse is of course that it has made the idea of structural racism seem almost archaic, a tattered artifact that will soon be overcome with the help of globalization, free-market democracy, or even miscegenation. When I point to the aforementioned trajectories of Asian American disenfranchisement, I am clearly making a case for racialized structures of exclusion; however, catalyzed by faith in a cosmopolitan and postracial self, students are often reluctant to agree that these structures implicate them.

One of the consequences of postracial discourse is of course that it has made the idea of structural racism seem almost archaic, a tattered artifact that will soon be overcome with the help of globalization, free-market democracy, or even miscegenation.

Furthermore, civil rights seem to frequently still be imagined along a black/white axis with contemporary public challenges to such thinking—anti-brown and yellow xenophobia and persecution, coupled with quotidian infractions of civil liberties and the Cold War resonance of “If You See Something Say Something”—seen as either globalization-induced ills or relatively benign, even innocent (and therefore of course successful) state surveillance. Awareness of “racial profiling” seems to fit somewhere in this scheme, but for those who experience this “profiling” most acutely, even violently, there is little incentive to step forward and identify as someone marked by the past as well as the present. As a slight aside, what kills me are also the students who seem so convinced of the incompetence of the state that they cannot imagine being successfully policed, never mind the fact that the effort to police needs to be interrogated in the first place.

I have no overarching conclusion, since these are simply notes on what I understand to be an ever-evolving process of working in the classroom. Let me stress, however, that my observations of “students” are not meant to imply that they are a naïve, ignorant, or homogeneous group. I interpret their wide-ranging belief systems as being reflective of a number of broader challenges: the inadequacy of K-12 treatment of Asian American history and experience, the illusion of personal reinvention vis-à-vis social media, family histories of sacrifice with a subsequent insistence upon personal triumph—to name only a few of the forces they are subject to as youth, immigrants, English language learners, workers, sons, daughters. This last point resonates most powerfully since I know that the vast majority of the students I work with come from immigrant backgrounds. As first- or second-generation immigrants from Bangladesh, the Ukraine, Tibet, Poland, Afghanistan—and then often first-generation college students (at least in this country)—my students face high stakes when it comes to believing that an education affords opportunity and that anything structural is meant to include, not exclude.

As I write this text, it dawns on me that the classroom experiences I had before 9/11 were as a student: only in the years immediately following 2001 did I come into my own as an educator. Consequently, my sense of past and present shifts in the field must be read through another “pre-” and “post-.” As a student—both similar to and vastly different from the undergraduates I work with now—I must also have wanted to believe that I had a say in the construction of my identity. At the same time, I also recall an acute sense of excitement and pride to be a subject on the margins with a growing suspicion of the center. The study of gender—in particular, then, repeated readings of Anzaldúa—was useful to my understanding of the provocative possibilities of locating my racial/gender/class identity on the margins in order to potentially displace or relocate the center.

The 2011 classroom is undeniably very different than its early 90s counterpart, but as the challenges are continuously shifting, so are, thankfully, the contours of Asian America. A number of critical and generous teachers helped me understand the possibilities of this generative dialectic between center and margins, and my hope is that I can do the same for the students I work with. By presenting “Asian America” as an unstable and open structure, I hope to make the broader point that identity—disciplinary, individual, collective—bears the same qualities of instability and contradiction where an understanding of the other always implicates the self.

¹The reading that has been most useful is Erika Lee’s “The Chinese Exclusion Example.”

A note about the art: The image that appears atop of this conversation is adapted from the artist Tomie Arai’s “The Shape of Me,” a silkscreen monoprint created in response to a national call to artists issued by the American Friends Service Committee for the 2011 exhibition entitled “Windows and Mirrors: Reflections on the War in Afghanistan.” We are grateful to collaborate with Tomie for our notebook Living in Echo. Find more of Tomie Arai’s work here.