“I have a mole on the bottom of my foot, and some of my more superstitious relatives told me that if you have a mole on the sole of one foot, you’ll always yearn to visit new places more than most.”

November 28, 2012

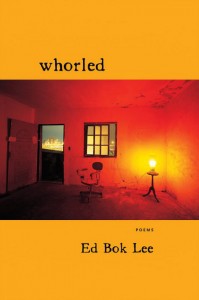

Ed Bok Lee is on a roll. When he’s not tearing it up at karaoke or traveling through gorgeously eroded landscapes, he seems to be pocketing yet another literary prize. His books, Real Karaoke People (New Rivers) and Whorled (Coffee House), have won a PEN/Open Book Award, a Member’s Choice Asian American Literary Award, a Minnesota Book Award, and most recently an American Book Award. Lee’s also won grants from the NEA, the Jerome Foundation, and numerous other fellowships.

All this with just two books of poems—from a man who never intended to be a poet.

Lee grew up in Seoul, was raised in the Midwest, and has since lived in the Bay Area, Central Asia, and New England. He lives in Minneapolis now, where he teaches and is a fixture in its writing community. His poems bear the trace of his travels and capture the complex dynamics between desire, memory, and dislocation that haunt most immigrant or transnational experiences. Where Lee’s work shines, though, is in his ability to draw grace from the most forlorn, even squalid, scenarios, and his careful attention to voice. The various friends, overheard strangers, lovers, and family members that populate his poems sparkle with the full roundness of life.

What makes this guy tick, and how is it that his poems are so good? I wanted to know. He was kind enough to field a few questions while combatting the flu.

—Sueyeun Juliette Lee

Sueyeun Juliette Lee: Firstly, congratulations! How badass did you feel when you heard you won the 2012 American Book Award prize for your second book of poems, Whorled? This is just one of several awards, too! Has being such a prestigious prize-winner changed things for you?

Ed Bok Lee: Thanks. The American Book Award folks are bona fide angels. You know, awards can help connect books and readers, and I’m told it’s helped with that.

You’ve wandered all over the globe, most recently spending some time in the deserts of the Southwest. Your poems often serve as postcards and snapshots from your travels, or are distilled from your experiences abroad. Are there any particular places that either break your heart or have entered your bloodstream?

I have a mole on the bottom of my foot, and some of my more superstitious relatives told me when I was a kid that if you have a mole on the sole of one foot, you’ll always yearn to visit new places more than most. I don’t know what effect that had exactly, but after high school, I traveled around the US, Canada, and Mexico for a couple of years, working temp-labor jobs. This was before the Internet or cell phones, and that was the most direct route to fulfilling some deep need to travel, without the possibility of having to officially kill someone.

More lately, I’ve ended up in the deserts of the Southwest and Southern California for months at a time. I love that region. I suspect the harsh but gorgeous terrain erodes things within. It erodes the wax buildup over the perceptions, for one. And clears the static buildup over the psyche. All travel does that, to some extent; it refreshes the senses, though in different ways. Sometimes it’s not via erosion, but fertilization of the imagination with new smells, sounds, sights, et cetera. But for something more than tourism to happen, I think you really have to be ready to embrace its “shadow” side. Just like all people and characters have shadow sides, so too do places. And “bloodstream” is a good word to use. You really get to know a body of water when you accidentally swallow some, preferably through the nose. Or a desert when thirty-seven microscopic thorns get lodged in your hand, and for the next few days you dream the same exact dream. I don’t mean to sound hippie-dippy, but I think you have to get beyond the beauty (and horror, which is always there too) of any real place, and that’s hard to do unless something breaks the seal of your separation from it.

I also like reading about geological history. Having lived in North Dakota, I love the Badlands, which were once an ocean, then swamps, then tundra, et cetera. Again, I suspect going there helps erode layers of one’s “civilized” mind; helps to get closer to that core, that beautiful wound at the center of what it means to be human. But, you know, every place is interesting, and heart-breaking in a different way. I found the Central Asian steppe to be consciousness-altering, and some forests in Russia, with woodland leaves so green they’re blue. I love cities too, like Paris, New York, Moscow, Istanbul, Taipei, Vancouver, Seoul, Mexico City, Berlin, Almaty, many others.

But to paraphrase Don DeLillo, there’s nothing so boring as a well-traveled person. First off, any international business employee has probably traveled more than I have. Secondly, as a kid, we went on exactly one family vacation, and it was to my aunt’s basement two states over. So I’m aware any travel is a great privilege. I’m re-reading Calvino’s INVISIBLE CITIES right now, and in one sense, it’s reminding me that in the past several years, almost every new place I’ve visited feels vaguely like an old scribbled poem I just found in the pocket of an old pair of pants I haven’t worn in years.

Your interest in deserts as eroded landscapes is really making sense to me now. You stated once that you started traveling when you were younger to basically sort yourself out—to find a consciousness that wasn’t imposed upon you or borrowed. Through your poems, you seem to have found a way to sit with anger, suffering, heartbreak—even ugliness and squalor—that lets you still see beauty and grace, too. What helps or has helped you get to this space?

The imagination is seething below all the constructs we inherit and accumulate. It’s the energy coming up through the earth and sand and red rocks and scars and ego and trauma (human, historical, geological). As I mentioned, eroding the accumulation of garbage over one’s senses and consciousness, I think, helps. Reading can help clear things away. Any form of concentrated awareness, actually. Imagine your head is a piece of hardened cheese and the outer world is a cheese grater. The Cheese Maker’s soul, if the cheese was made with love, is at the center of your head. You want to share its flesh and scratch its core. But what is at the center of the Cheese Maker’s head? More cheese? Or pure, blissful cheese-ness eternally? All I know is it’s easy to get caught up in the actual cheese sometimes, and forget the love with which it has to be made to be great, genuinely nourishing and lovable cheese. The opposite is weak cheese you eat and forget you’ve ever tasted a moment later. But a great cheese, made with love, from animal to final form…

Cheese! Wow. What is at our center anyway? I can see that question in your work. Your poems spin and un-spin the complex threads that compose us, showing us how we are living, real-time spirits who have to deal with a ton of crap, basically. For example, I was thinking about your poem “If in America,” a response to that shootout between Chai Soua Vang and some hunters over a deer stand in Wisconsin. I can see how your background in playwriting and journalism really reflects an overall interest in humanity. What surprises or fascinates you most about people?

One thing is that we always seem to be forgetting the essence of this Lorca quote: “The iguana will bite he who does not dream.”

Your poetry is so passionate without spinning out of control. For example, “Sweet Men” might be one of the most interestingly sexy poems ever. You move from a memory of your father disciplining you with a 2×4 to considering some surprisingly erotic, tender memories. I could say volumes about that, but I’ll restrain myself. What’s erotic to you about poetry? What turns you on?

Metaphor-making is pleasurable in any form. At the deepest sub-stratum of all poetry, it seems to me, aches the interconnectedness of everything. So fusing two or more disparate things together in new, enlivening, meaningful ways—whether they’re images or ideas or colors or notes of music or culinary ingredients or bodies or subtle moments in time—feels very erotic.

Tell me more about your interests. Are there any things that our readers would be surprised to hear you are into?

The first concert I ever went to was Iron Maiden? I love documentaries about animals?

I’m suspicious of anyone who doesn’t! Any particular ones?

I just saw “Animal Odd Couples.” It’s about special, cross-species friendships between animals, like between a tortoise and a goose, a deer and a dog, a cheetah and a retriever. There’s a goat that has more love and compassion than probably any human I know, with none of the ego. He guides an old, blind horse around for over a decade, for no apparent reason other than love and compassion. I experienced something like this in the desert. The animals look out for one another. And sometimes they ask you for help, as well.

What’s up next for you? What projects are you working on?

Poems, and a fiction manuscript.

Do you want to say more about this new project, or is it still too tender and dear to bring outside?

It probably still can’t yet speak for itself, so I better not try, lest it punish me, the vindictive bastard.

For my final question, I’d like for us to talk a bit about your title poem, “Whorled.” It opens “Dear speaker in a future age.” And you’re being literal when you say “speaker”—you are terrifically concerned about language extinction and what that might mean for the possibilities of human imagination and Being. I was interested in how this poem is basically an impossible missive—a letter whose receipt you can never confirm. Is that the heart of poetry? Of writing? How does “Whorled” speak? How do you?

Maybe all poetry is a dialogue with the impossible. With that poem, I was partly thinking about Pessoa’s notion of nostalgia for the future. Also, I’ve been contemplating for the past two decades the fact that the final living speaker of a world language dies every two weeks. By 2050, ninety percent of the 6,000-some living languages today are scheduled to have gone extinct, largely due to corporate and colonial advancement. And, of course, not just the languages are going extinct, but the corresponding cultures, with their speakers’ knowledge of cosmology, history, nature, health, psyche, myth, science, music, artistry, and ways of perceiving, thinking about, and assigning values within the world.

We work very hard to save the bison and certain kinds of endangered toads and flowers, as we should. Laws are created to protect the Aztec and Egyptian pyramids or save old, often defunct, Gothic cathedrals in Europe from being torn down when the land could easily be more profitable by erecting a McDonald’s or strip mall, because we value those monumental creations of the past. They help orient us, help remind us that the current way is not the only way, or even the best, and certainly not always the most beautiful or majestic or well-constructed way. And, yet, when an endangered language and culture—each one an invisible kingdom built over eons, speaker by speaker, word by word like a monumental, collective work of art—goes extinct, we call that “progress.”

I’m not sure how the poem speaks, but maybe because I write poetry, and believe language can so deeply shape and nuance a speaker’s reality and imagination, the increasing extinction of languages feels so tragic. How do you translate duende into English? Or han (a Korean word for something like deeply regretful, resentful, passive, yet not hopeless sorrow)? And every language and culture has a multitude of words and concepts that are untranslatable into another language. Where does that wisdom, that nuance and beauty, that oral and spiritual technology go when an eons-old culture’s language evaporates? It feels like dreams disappearing. Words are magic-making animators. But we are born into language, not the other way around.

Click through to read Ed Bok Lee’s poem, “Whorled.”