On Chinatowns around the world, writing about teen girlhood, and making music.

January 22, 2021

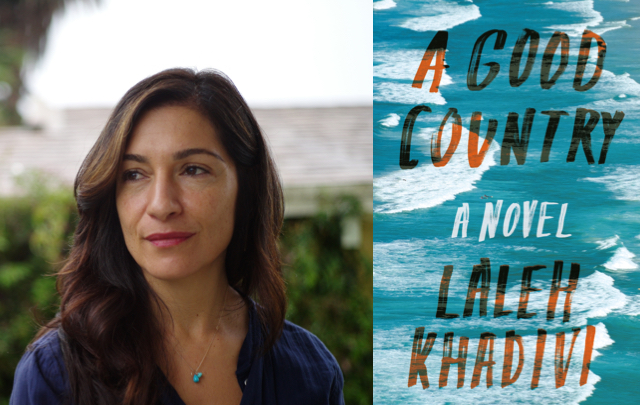

Jamie Marina Lau is a multidisciplinary writer and artist, which is apparent in her debut novel, Pink Mountain on Locust Island. It is my new favorite book about art scams and boasts lyrical prose, Technicolor scenes, and provocative characters, all through the lens of a fifteen-year-old Chinese Australian girl named Monk.

The world in which the acerbic protagonist experiences is grimy and unforgiving, yet rich and eccentric. Lau and I have never been to each other’s cities, but the Chinatown Lau writes about feels deeply familiar, from the sensorial descriptions of food to the characters who have immigrated and brought stories from the past to the present. Monk navigates the blossoming relationship between her washed-out former art professor father and her nineteen-year-old crush and painting protégé, who goes by the name of Santa Coy. Monk’s father becomes obsessed with Santa Coy’s work, which results in the two conspiring an art scheme run out of the apartment Monk and her father inhabit. Written in fragments as gut-punching and vivid as the writing of Weike Wang and Jenny Offill, Pink Mountain will give you a thorough tour of the tumultuous underground art world that Monk has to balance on her shoulders, along with the everyday problems she runs into as a young girl.

Although I am in my twenties now, my fifteen-year-old self felt empowered by Monk’s perceptive and visceral voice. I talked to Lau, who wrote the novel when she was nineteen, over a WhatsApp video call, in which we discussed the similarities between our countries and cultures. We discussed how this novel is an exercise for teenage girls to break away from feeling angry and confined at fifteen, as well as topics including city versus suburban life, interiority, the passive voice, and of course, astrology.

Pink Mountain, which was released this past September by Coffee House Press in the US, is just the beginning of Lau’s burgeoning career in writing and music (She also produces tranquil and layered music under the name ZK king.) Hachette Australia will be re-releasing Pink Mountain, alongside her sophomore novel, Gunk Baby, later this year.

Read an excerpt from Pink Mountain on Locust Island here.

—Ruth Minah Buchwald

RMB: I love this book. It’s so funny and I’ve heard many people describe it as cinematic, which I think is very accurate.

JML: Thank you, that means a lot. I don’t usually talk to many people who have read it recently because it came out so long ago. I wrote the book in 2016 and it was published here in 2018, so I’d be interested to talk about how it’s shaped my writing.

I was 19 when I wrote the book, and very different from where I’m at now at 23. During the 18-25-year-old time range, you just become a different person every few months, so it feels like a long time ago. When I talk about it, it really feels like I’m talking about a previous version of myself. It’s almost become a thought experiment rather than a book. It’s actually more personal than I thought it was.

RMB: I appreciated the setting so much in this. I’ve never been to Australia, but the setting of Chinatown in an unnamed Australian city felt so familiar to the diasporic communities I know in the States. I grew up in a community where there fortunately was an enclave of Korean Americans who had their own businesses and organizations in surrounding towns. How did you approach writing this world where an Asian population was at the forefront, as the Chinese diaspora is rarely represented in Australian literature and media?

JML: I grew up in three different East Asian-populated diasporic communities: one in Sydney and two in Melbourne. I never wanted to specify too much of this cultural hub in the middle of the city, although I feel like I did because it was easier to place globally and universally. The idea of Chinatown being within a larger city and it being a money-making business is very specific to Australia. The Chinatown here is just a whole bunch of East Asian restaurants, not even Chinese. The idea of a commodity of a commodity.

I’ve been to Koreatown in Los Angeles and Chinatown in San Francisco. It was really interesting going to those places and seeing how it felt the same because there were a lot of East Asian immigrants living there and that’s where they found solidarity. Chinatown’s always been an economic hub, whereas in Australia, it’s very orientalized and othered, but it is the only opportunity for Asian immigrants to be able to make a living for themselves. It’s an interesting comparison to make for me because I hadn’t actually been to the US until after I wrote the book. I was actually surprised at how it felt a bit more like the Chinatown I was writing in Pink Mountain than the one here.

[Koreatown in LA and Chinatown in SF] were the first places that I was in, in America. It felt very much like the suburbs I grew up in. It was really comforting, but at the same time, it was an alternate reality. I went to this claypot place in San Francisco Chinatown and it felt very homey, as if my Bobo was cooking me food. There were firecrackers going off because we were there during Chinese New Year and it was really cool. It felt very familial.

RMB: The protagonist, Monk, is a teenager with a unique perspective on the process of creating art. What do you make of inherent love-hate relationships people have with art, whether they be the artist or observer?

JML: It’s interesting that you bring Monk into the idea of creating and art-making because I always saw her as the observer. That’s an interesting point–that she is very much attempting to make art out of herself in the way that she presents herself. Now reflecting on it, I feel like there is often a blurred line between the idea of celebrity and the art that the celebrity creates. To be an artist now, you have to be the artist, as well as make the art. Monk is of a generation and age when you’re trying to create a character and persona for yourself anyway.

She’s very much taking the idea of being an artist as just being the artist and not creating art. She wants to create art, but she thinks that in order to create art, you already have to be an artistic person. The idea of the artist as celebrity has been something that has been happening over the years and continually happening, like how Instagram evolved into TikTok and all these ways of becoming art rather than creating art–it’s not a bad or good thing, just an observation. The idea of creating a profile and having the pictures suit you and you become the pictures. I wanted to personify and manifest that idea of that happening to our generation, Gen Z, and how that becomes a conflict as well.

RMB: In addition to that generational divide being a conflict, were there other conflicts that came out of her love-hate relationship with art? Perhaps divisions due to gender and race?

JML: I always like to think about the generational and the racial divides being personified through the characters of Santa Coy and Monk’s father. They’re both seeking to become artists. They romanticize the idea of artistry but come from different circumstances. If you bring other people of different racial and gender backgrounds into it as well, there are very deep complexities.

Here in Australia, there is a point system when you immigrate. In order to become a full citizen, you need to obtain a certain amount of points. Let’s say you move to regional Australia, out in the country, and you get twenty points, but if you stay in the city, you only get five points. If you’re of East Asian descent and you study STEM, you get twenty points, but if you study some sort of art, you get five points. I was talking to someone who had recently immigrated and they had to end up studying Biomed because they wanted to immigrate quicker and for the process to be easier to be able to assimilate.

With the [character of the] father, he has to sacrifice a lot more to become an artist even though he is a very hateable person in the book. You can understand his struggles if you were a person of color and/or an immigrant. It’s a different kind of struggle to Santa Coy’s struggle, as he is someone who is following the trends of being an artist without consequences.

It’s that difference between who can be an artist and who decides to be an artist, the latter of which would be Santa Coy. I’ve been thinking recently: Who do we need to become an artist when so much of our media and pop culture is dominated by white voices? With becoming an artist, there’s a risk of becoming tokenized and being completely used up.

RMB: It’s funny to me how Monk is described as “drifting through a monotonous existence” when I definitely see her as a modern-day flâneur. Did you envision her that way from the beginning?

JML: My next book is also written in first person. It’s interesting that we grew up reading The Catcher in the Rye and Jack Kerouac. There’s a passive aggression to the idea of these centralized male narrators of the book, and I found that really interesting because before I wrote this book, I had written four others as a teenager. I felt this need to make my female characters seem more passive because that’s how they would be treated if they were in another piece of literary fiction. Monk was really the first character that made me want to say everything that I was thinking, very stream of consciousness. I didn’t necessarily set out to write her in that very specific voice of being an active observer, but it just happened because I had almost replaced that passiveness with that flowy perception and receiving of the reality around her. A lot of the descriptions in the book replace that passiveness with poeticness because that’s the only way that I could unlearn envisioning myself, or in envisioning someone like myself, in a novel.

RMB: I’m really fascinated by the fragments and negative space in this book. Can you speak more about that and if there were any influences you referenced?

JML: I studied art history and I always thought that negative space in art is interesting, as well as the use of it increasing over time, especially in interior design. It used to be ornamental and now we take advantage of it.

I’m about to move into my own space for the first time, so I’ve been thinking of furniture and lack of furniture. It’s really interesting how we’re beginning to cut down in order to emphasize what we have. The idea of having negative space in literature gives us the opportunity to imagine for ourselves that we live in such a high content receiving generation and in order to receive content, we have to constantly be switched on. With the social platforms we have, we don’t necessarily get opportunities to exercise our imagination.

When I wrote this book, I wasn’t really thinking about that. It happened to be like that, but speaking now about it, I still believe in that concept of having negative space and fragments. I used to think that I did it because we don’t have the attention spans to read long novels anymore, but now I’m seeing it as an opportunity for us to give our very quick-moving brains a break and exercise to exercise imagination. I hope that comes across because I have been told that the book is easier to read and it does cater to how we read and consume things now, but I also like to think that it wasn’t just for that purpose. It also complements the psychology of consumption that we have nowadays and it can be a less negative and more positive thing.

I was also reading and studying a lot of poetry at the time. I was referring a lot back to this e.e. cummings book that I found in my house randomly. I was interested in his choice of indenting or not indenting. Also, his choice of every word being art itself was really exciting to me. [cummings] would isolate each word.

I was looking at artists that use space very indulgently. [Jean-Michel] Basquiat was very much a theme in this book because I was very interested in the commodity of him and how people used him and how he was often praised as the Black star of the art world. Obviously, growing up in a white space myself, it really interested me how people are attracted to an experience that’s different from theirs in a very perverted way. That’s what Santa Coy was about.

[Writing this book] was a very blurred period for sure. It was pretty much just YouTube rabbit holes. I wouldn’t even register what I was consuming. It was such a blur–I can’t even remember the things I listened to, which is such a shame because I wish I noted down everything I did. It was a mess. I feel like it’s represented in the book, how chaotic my consumption was during that time.

RMB: How did you come up with the title?

JML: That’s something that just happened. It happens with all my books. Originally, we weren’t going to keep it and I fought for it anyway. I just typed it out on a document. I started writing the book in a literature class at uni and I wrote the first chapter, “Panther.” I didn’t change it at all. It was a poem and on top of that, I wrote “Pink Mountain on Locust Mountain,” and I thought, “That’s nothing!” and it kind of stuck in that document. I kept adding titles and fragments of the black text. I thought it was going to be poetry and turn into a little zine or something. For a long time, it was just a zine, and I didn’t even really picture it as a novel until I had gotten halfway through. Obviously, when you title something, it becomes nostalgic and something that you want to view it through. I feel like the title actually made the book, rather than the book making the title.

RMB: It’s so great and visceral, and I’m reminded of what you said before about each word being art–that definitely comes across.

JML: I definitely am such an aestheticist. Is that a word?

RMB: Yes!

JML: I was definitely such a superficial person that way. A word won’t even make sense in a sentence describing something and I won’t care. I’m so snobby about it because I’m like, “It can!” Language isn’t clear cut. Maybe I’m just defensive because English was my second language, but it is my first now.

RMB: You have a second novel, Gunk Baby, coming out. Can you talk about your transition from writing about city life to writing about suburbia?

JML: I didn’t mean to do that! The second book came about when I was waiting for this book to be published. Gunk Baby almost feels like an honorary sequel, but it’s not really connected to Pink Mountain. It feels like they’re in the same world, but because I’ve changed as a person, Gunk Baby has evolved into this book that probably wouldn’t even be recognizable next to Pink Mountain. I don’t deal with the aesthetic themes that I dealt with in Pink Mountain. I didn’t use any special format to write it in. For me, it wasn’t even stream of consciousness.

I’m in the last edit and it feels like I haven’t put the two together yet because one of them isn’t entirely complete. Gunk Baby definitely deals with interior design, as we were talking about before. It also deals with art and intangible forms of career paths, like Pink Mountain does. Also religion, drugs, and people coming to things for reassurance, to reinforce their humanity in a world that is ruled by capitalist modes. Gunk Baby is about the other side of that. It’s how we come to material things to make up for who we are. We reflect ourselves in the way that we decorate our homes. We reflect ourselves in our rituals now. It’s very much about the tangible [rather] than the intangible.

I’ve never put the two books together like that, so it’s strange to talk about the differences because they are really different books. I wrote a lot of Gunk Baby over the last four years, whereas I wrote Pink Mountain in a few months. It definitely doesn’t feel like that burst of energy that I had when I wrote Pink Mountain. Gunk Baby feels really considered and I do make a lot of references that I’ve always been afraid to include in literature. I’ve always been sort of afraid to talk about my opinions, which is why I’m a fiction writer, but I feel like I’m sort of getting there and I’m learning through this book, how to implement my personal beliefs and ethics into a book, whereas Pink Mountain was an exploration of the state of mind that I was in when I was a teenager.

I saw someone tag me in a post about how my book uses the word “fat” a lot. I’ve been reflecting on how Pink Mountain is a lot more personal in that sense of talking about my experience with my body image and my experience of receiving that idea of an expected body unto me and how that influenced the way that you would even look at the space around you, so both books are really about space and shape, and how we receive the exterior of our bodies in our minds, and how we use descriptions of ourselves to describe the space around us. Pink Mountain was a lot more personal. Gunk Baby is definitely more of a traditional novel.

RMB: I’m interested in your creative practice when it comes to your music, as you are also an incredible music producer. Can you speak about how music intercepts with your writing practice and vice versa?

JML: It has been very conflicting, which it shouldn’t be. I’m slowly unlearning this idea that you have to be or embody the art. I’m trying to understand that whatever happens, happens, and whatever form my ideas take shape in, it’s okay.

I do have to be in very different mindsets if I’m creating music versus when I’m writing. I would say my Pisces rising is how I create music and my Scorpio moon is how I write, so I’m very introverted, judgemental, and critical. I wouldn’t say that Scorpios are inherently pessimistic, but that definitely comes out in me because I’m an Aquarius sun.

When I make music, I’m more dreamy and celebrating life. I’m feeling that life can be represented in the textures of the music I make, but when I’m writing, I’m like, “Fuck everything!” It’s just me being critical of everyone and being a nihilist. I’ve recently come to terms that I can be both, that there is this duality. I do draw influences from books for my music and I do draw inspiration from music for my writing. I’m not sure how it comes across to other people, but listening to my music and reading my work feels like I’m two completely different people, but that’s probably because I’m hyper-aware of the process of growth that I am.