Bangladeshi app-based delivery workers must turn to each other for safety in NYC

July 22, 2022

Outside of Madina Masjid in the Lower East Side, a pair of friends maneuver in lockstep through a blur of bikes, helmets, and bulky backpacks.

“We came together and now we go together,” grins Emon, twenty-three, nodding towards his roommate and fellow student, Mujahid, twenty-four.

Their exchange is rhythmic, Bangla bouncing back and forth and occasionally punctuated by quiet laughter. But Emon and Mujahid barely look at each other; their heads are tilted downwards, eyes fixated on their phones while their fingers tap to secure the next delivery.

In New York City, an estimated eighty thousand people, work as couriers for food delivery apps—enough to fill the seats of Madison Square Garden four times over. Among them, an understanding hovers in the air. To make the most of one’s shift, you’d better move fast. No time to dawdle when your wages rely on an algorithmic evaluation. However, to survive in New York City, food delivery workers must look out for one another. Traveling in packs, communicating on WhatsApp, monitoring each other’s bikes, and pausing a shift to help a peer in need are all communal practices for these workers who have come to rely on camaraderie for survival.

“My next order has already started—now is the best time because of the surge!” Mujahid calls out as his e-bike ejects him onto 11th Street.

Since the start of the pandemic, usage of on-demand delivery apps has proliferated. Hailed as lifelines for beloved restaurants, apps like DoorDash, GrubHub, and UberEats offered a way for New Yorkers to satisfy their food cravings without descending into the dangers of the city. As these companies broke records with billion-dollar revenues, numbers that continue to rise today, they also grew increasingly reliant on an immigrant workforce for their delivery operations.

Young men from Latin America, South Asia, and West Africa make up the vast majority of these laborers, who the apps classify as independent contractors. This status excludes them from standard workers’ benefits such as health insurance, workers’ compensation, sick time, and paid leave. For those who are undocumented, social safety net programs like Medicaid, food stamps, and unemployment insurance are not an option. In other words, they’re on their own.

Delivery workers from Bangladesh represent one of the largest demographics working for food delivery apps. They need not look far to find each other. Deemed the city’s fastest growing immigrant group, they tend to live in community with one another, sometimes in notoriously overcrowded homes. While the gig economy beckons workers with the promise of quick earnings, this South Asian community experiences some of the highest rates of poverty in the city. Recent reports show that Bangladeshi New Yorkers hold the lowest median household income of all Asian communities in the city. During the pandemic, a stunning 82 percent were classified as essential workers, making the decision to earn an income and protect one’s health a daily trade-off.

Muzammil Hossain first learned about the apps in 2015. At the time, bikes donning the branding of two-syllable tech companies were only lightly freckled across the city and Hossain was working for a pizza shop. Enticed by the promise of not having to report to a boss or stick to a rigid schedule, he left his job to pursue a more flexible lifestyle with UberEats. Today, he manages work across several apps, a common strategy for those seeking to maximize earnings.

Last summer, a grisly incident shifted Hossain’s perspective on the perks of the job. While delivering to a customer in Williamsburg, he noticed someone cutting the lock of another delivery worker’s unattended bike. When a scuffle broke out, Hossain watched in terror as the thief plunged a knife into the delivery worker’s torso.

“If you saw his pain yourself, you’d understand how dangerous this is. All blood,” he shuddered.

With street safety in New York City at a perilous low, the lives of Bangladeshi delivery workers seem to dangle in a ceaseless state of suspense. In a 2021 survey of 500 New York City delivery workers conducted by the Worker’s Justice Project (WJP) and Cornell’s Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR) School, participants reported being consistently exposed to violence while on the job.

The summer of 2021 was particularly gruesome for Bangladeshi delivery workers. Borkot Ullah, a twenty-four-year-old immigrant seeking political asylum, was struck in a hit-and-run in Lower Manhattan. Tarek Aziz was working a late-night shift when he fell into an unmarked construction site in East Brooklyn and suffered fatal head injuries. Salauddin Bablu, an immigrant also escaping political persecution, was killed by a bike thief while he rested on a park bench in Manhattan’s Sara D. Roosevelt Park.

“We really don’t have good measures to protect the workers,” explains Maria Figueroa, dean of the Labor Studies School at SUNY Empire State College and co-author of the 2021 research study. “The essential workers are precisely the ones that are most vulnerable to any safety issue.”

For many of these workers, navigating intractable danger is a familiar experience. The WJP and ILR School study revealed that app-based workers often exist on the fringes of their own ethnic communities. For instance, a large portion of Latin American delivery workers are indigenous and have been subject to violence in their homeland for centuries. Many Chinese delivery workers are originally from the Fujian province and have historically endured profound dangers to enter the United States. Among Bangladeshi delivery workers, education, income, and English proficiency levels are all significantly lower than those of their South Asian immigrant counterparts.

Ullah, one of the young men who lost his life on the job in 2021, had been a member of a grassroots community organization for low-wage workers, Desis Rising Up & Moving (DRUM). In lieu of what they viewed as adequate support from the city and apps upon his passing, DRUM set up a GoFundMe page and raised over $30,000 for a funeral and vigil, and to send his body home to Bangladesh. By the end of that summer, over 450 Bangladeshi delivery workers submitted requests to join DRUM.

“When they saw that we were supporting Borkot, they were thinking, ‘I’m also alone. If something happened with me, who’s going to help me?’” explains Kazi Fouzia, the organizing director of DRUM and lead organizer for the delivery workers. “That insecurity inside of their hearts is probably what causes them to join hundreds together.”

DRUM is somewhat of an incubator for immigrant organizers in New York City. For more than twenty years, the organization has brought together thousands of low-wage South Asian and Indo-Caribbean immigrant workers to fight for racial justice and labor rights. Through education on personal rights, election preparation, and alliance building with other communities, members learn the art of speaking truth to power. When hundreds of delivery workers requested membership last summer, however, Fouzia worried they had signed up with the wrong expectations. “Our twenty-dollar membership dues are not your life insurance,” she explains. “If you join, you have to be an active member.”

The expectations for members are simple—show up and stand up for each other. From marching to Albany to confront the governor to protesting wrongful convictions outside of courthouses, DRUM campaigns are vigorous and consistent. Earlier this summer, for example, prosecutors in Queens dropped charges against a young Guyanese immigrant whose unjust incarceration was protested for over a year and a half by DRUM.

“We have to have something to know ourselves. We need to have community, we need to have unity.” Hossain argued. “We don’t even know our rights. Before, I didn’t talk to the delivery guys, but now whenever I see anyone, I try to talk.”

In this line of work, which draws laborers to disparate parts of the city, DRUM also offers space for these workers to simply gather: “Everyday, I just talk to delivery workers about their experiences—how a customer or restaurant owner disrespects them, or how the apps stole their money or are not paying them,” Fouzia explains. “But I tell them, if you just talk about the problem, it will never be the solution—you have to fight. And when can you fight? When you are organized.”

Early last year, a labor organization of predominantly Latin American delivery workers was fed up with the city government’s inaction to protect workers and set forth a prioritized policy agenda. Los Deliveristas Unidos (“Deliveristas”) collaborated with the authors of the 2021 delivery workers’ survey to propose new labor standards and rights for app-based couriers. When the City Council signed a package of six bills into law last September, the first of their kind in the nation, labor activists around the country celebrated.

But the Deliveristas are not letting policymakers off the hook. The laws, which have been going into effect in installments, are largely considered common sense improvements, including access to restaurant bathrooms and transparency into payments. Even some app companies are in support. The Deliveristas’ next frontier will include sharper demands such as equitable minimum pay, stricter street safety measures, and building their independent labor union. To drive this policy agenda forward, they are turning to their peers.

“We can’t do this by ourselves,” declares Manny Ramirez, a delivery worker and organizer of the Deliveristas. “This started with a Latinx group but we need to get more united with DRUM, with African people, with Asian people, with English speakers. If we need change, then we need to have more power together.”

For the Bangladeshi delivery workers at DRUM, the invitation to work with the Deliveristas is welcomed. “We always believe that we need to create a multi-racial platform where we can see each other, who is also suffering, and who also has issues like me,” asserts Fouzia. “That way we can ask how we can fight together and hold these corporations accountable.”

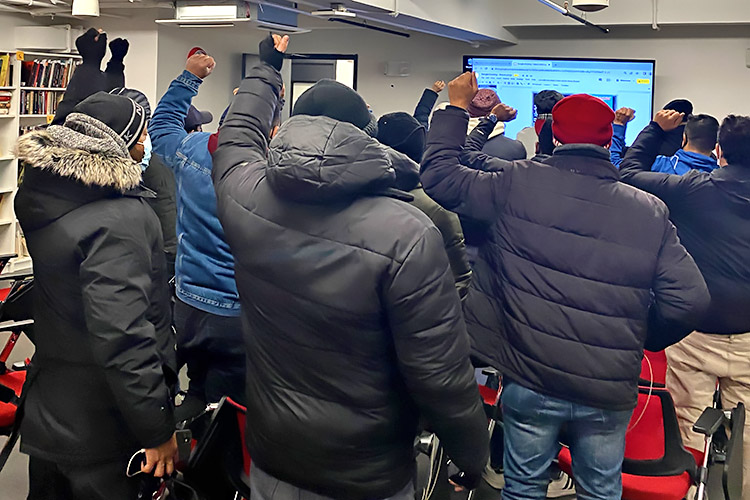

Every Wednesday, the Deliveristas hold an open invite for South Asian delivery workers to visit their Williamsburg office. Their offerings are extensive—like tune-ups, phone charging stations, safe areas for mid-day meals, fundraising, legal aid, trainings on workers’ rights, and the distribution of safety equipment. At a Deliveristas and DRUM meeting in April, the conversation flitted seamlessly between Spanish, Bangla, and English as the workers exchanged warm affections.

“This place is now your place,” announced one of the Deliveristas, stretching his arms out wide as if to embrace the collective feeling of safety. “And wave to me if you see me in Manhattan.”

The solidarity among New York City’s delivery workers embodies a broader revival of the labor movement across the country. In recent months, a flurry of union activity including high profile wins and an almost 60 percent increase in petitions for union elections has captured the nation’s attention. A Gallup poll found that public support for unions is at its highest peak since 1965. Despite these shifts, the responsibility to organize for better conditions continues to fall to the most vulnerable workers.

“This is a solidarity of working class workers,” asserts Shahana Hanif of the 39th District and the city’s first Bangladeshi American and Muslim councilmember. Forced to wade through bewildering systems and treacherous jobs to stay afloat, Bangladeshi food delivery workers remain staunch at the forefront of their movement. “These are not workers who’ve come from immense wealth and the ways in which they’ve migrated to New York City have been under very harsh circumstances,” Hanif explains. “There is a lot to learn from them.”

As 2022 contorts into the deadliest year for street safety since 2014 and with customer tips for service workers steadily in decline, delivery workers carry on, zooming through humidity and congestion to place warm meals into the hands of New Yorkers.

Unlike precarious workers in other industries, these workers do not toil away in the shadows but out in the open and in plain sight. Lingering outside of apartment buildings, pacing in restaurant foyers, and inching forward at traffic lights, the helmeted man atop his trustworthy e-bike has become a fixture of the post-pandemic city landscape. Despite their ubiquity, these essential workers are learning that they can only rely on each other.

For organizers like Fouzia, solidarity is the antidote to this isolation. “If we are together with the Latino, Black, and other delivery workers, and we make sure our number is big and our power is big, then they will listen to us.”