The author of ‘Deceit and Other Possibilities’ on mischievous writing, how journalism feeds fiction, and getting to that “good place” in a short story

November 3, 2016

I can remember exactly when I knew I’d found a new favorite writer in Vanessa Hua: the moment I read “Accepted.” It was in Crab Orchard Review’s West Coast & Beyond issue. I knew right away who the story was about, but it didn’t matter. Even if I hadn’t known about this case, I would have still have been charmed by the main character’s wiliness, by her pluck, by her despair.

Behind every one of Vanessa Hua’s stories is a moment of clarity: it may not help the characters, they may be just as messed up at the end of the story as they are in the beginning, but this singular moment, this recognition, is enough to seal the bond between reader and writer and make us participants in the unfolding of Hua’s universe.

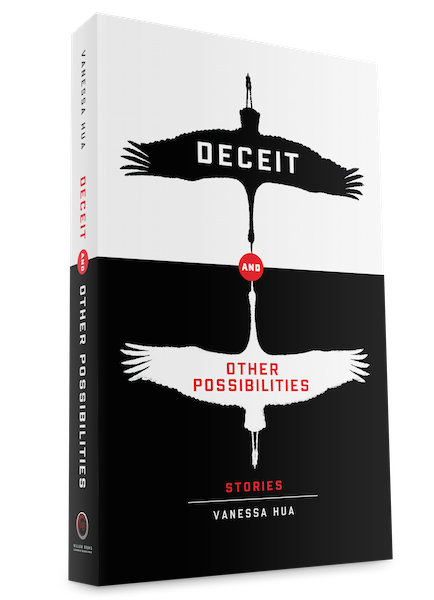

And what a sprawling universe it is! In her new collection of stories, Deceit and Other Possibilities, there’s tabloid Hong Kong and San Francisco’s Mission, there’s Mexico’s Morelia and Oakland’s Chinatown, there’s Big Sur and there’s Silicon Valley. There are delusional prophets and film heartthrobs, software engineers and grad students, snoopy girlfriends and mixed-up men. Most of us will never experience what happens in the stories—we will never have to lie about getting into Stanford, or about sexual preference—but our lives will be circumspect and dull, something Vanessa Hua’s characters definitely are not.

Come hear Vanessa Hua read alongside Janice Y.K. Lee at AAWW on Wednesday, November 9.

Marianne Villanueva: How do your stories originate? With a character, a memory, a line of dialogue, or an emotion?

Vanessa Hua: I don’t have a lot of patience, though I do an elephant’s memory, especially for embarrassing stories my friends tell me or that I witnessed! I have tried writing down story ideas, but ironically, I think I forget where I put those lists. What sticks with me is what will compel me enough to write later.

The stories may originate from a conversation, from something I read or see. At the time, I often don’t know it will spark fiction. But that inspiration lingers in my thoughts for weeks, months, years, shaped by whatever else I’m experiencing until at last I begin.

I majored in English, with an emphasis in creative writing, and got a Master’s in Media Studies. Journalism taught me the discipline of writing daily and on deadline, the freedom to observe and question and meet fascinating people. The media industry has cratered since I left daily journalism in 2007—a burning house, sliding off a cliff—but I can still highly recommend it. The funding models and platforms have changed, but the fundamental desire to shine on a light on untold stories remains.

Do you write in short bursts, or in one dedicated time period—a few hours, a day, several days, a week, a month? Do you write every day? What works for you?

During the week, I have time set aside when the twins are in kindergarten or when I have childcare. But I don’t have long hours of uninterrupted time to write fiction. I get tied up in meetings, or in an interview with a source, or something related to my book launch, or the mundane but necessary tasks related to my kids, taking them to a dental appointment, running a load of laundry, or making dinner.

I do what I can, and pick up where I left off the next day. I have to feed the weekly beast of writing a newspaper column.

The title of the collection isn’t Deceit: Collected Stories but instead Deceit and Other Possibilities. That is a wonderful title. The only story that has “Deceit” in it is “The Responsibility of Deceit.” Does this story have a personal significance for you?

When I submitted the manuscript to the Willow Books Literature Award, it carried the name of the story, “The Responsibility of Deceit,” which happens to be the first story I ever published. I began writing it in 2000 and it was published in 2005 in the Cream City Review. So, I’m fond of the story—you never forget your first!—and I thought it reflected the larger themes of the collection. It spoke to the ways that characters are deceitful, but with the best of intentions. And that deceit might be a strategy for survival, at least for awhile.

Who decided on the arrangement of the stories: you or your editors? What is more important: the first story, or the last story?

I decided on the order of the stories, subject to approval by my editor and publisher. For the first story, I’d been debating between “What We Have is What We Need” and “Line, Please” but I liked the idea of leading with the line “Perhaps you’ve heard of me?” for a debut collection. I also thought that story would set the expectation for the more comic moments in the collection.

First story, last, in-between—all important, for different reasons. I made sure the camping stories or the religious stories didn’t go back-to-back, to avoid seeming repetitive. They weren’t written back-to-back. I also considered how stories might build upon each other in terms of length or tone when deciding on how to arrange them.

For the first story, I hoped it would grab readers, compelling them to keep going, to buy it or check it out from the library. For the last story—if the reader makes it that far—I wanted one that reflects and amplifies the theme, as though the stories were building up to it, and leave readers with a final image that also alluded to the title. That image ended up being incorporated into the cover design.

Your plots skirt the edge of the absurd. How do you keep juggling so many balls in the air?

Sometimes (often?) reality is more fantastic and wild than fiction—so fantastic and wild that people in your workshop say, “That couldn’t possibly happen!” Where the story calls for it, I push the circumstances and the characters so that it dances at the edge but still has an emotional truth.

In terms of keeping the balls juggling, the deeper you get into a story, the more established your characters, the more the possibilities narrow until firebombs or bringing down a plane are all but inevitable.

I really enjoyed your stories’ pop cultural references. It makes reading them a lot of fun. Do those references appear on first draft, or do you add them in during revision?

Well, I tried to keep it to a minimum. Pop cultural references can be fleeting and cause readers to stumble in confusion, if they don’t catch the reference. Take name brands, for example. I explained to undergraduates in my fiction class that having their characters drink Grey Goose vodka doesn’t flesh out the character in a meaningful way. They’re repeating a marketing campaign! And such references can soon become outdated. When I asked my students if they’d heard of Clearly Canadian sodas and Saturn cars (discontinued brands from when I was a teenager), they stared at me blankly. Of course, such details can also situate us in a certain time and place. Jelly bracelets and acid wash Guess jeans are the essence of ‘80s fashion. And yet, I still feel the reference has to stand on its own—that is, with enough detail or description for the reader to figure it out. That said, I kept in my reference to David Hasselhoff because he’s withstood the test of time. And the phrase “out-Hasselhoff” also makes me laugh, and I hope readers will too.

Or do you mean references to characters and situations drawn from real life, from the pop culture universe? Though the protagonist in “Line, Please” was inspired by Hong Kong pop star Edison Chen, and the main character of “Accepted” is based loosely on a Stanford con, readers don’t have to know about those cases to know those characters, who are, in the end, of my own creation.

About “Accepted”: There wasn’t much in the official record, which gave me the freedom to invent. I didn’t report on it as a journalist, but noticed that case and other cases where Asian Americans had tried to deceive their parents rather than disappoint them.

Your stories have such different characters. But each story comes with an intricate physical landscape, and that gives the stories such a sense of realism. Have you visited all the settings? Sounds like you have.

Thank you. Setting can do so much to heighten conflict and also build out the characters, illustrating their world view. I haven’t experienced the same kind of desperate situations as my characters, but I’m glad to hear that you found the settings realistic.

As a reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle, I’ve had the opportunity to do extensive reporting in Chinatown. I also filed stories from abroad, including China and Hong Kong, where I visited factories and villages. I lived in the Mission District for years, I graduated from Stanford, and I have camped in the Sierras and on the coast, which gave me familiarity with those settings. For “The Deal,” I visited Korean mega-churches and a seminary. I’ve never been to East Africa, but I studied photos on Flickr, read church postings, watched many videos of mission trips, and discussed the story with a friend who is Korean American and a faithful Christian.

As a journalist, I traveled to Guangdong province, and visited the city of Guangzhou, where my grandmother grew up, but no family has lived there in more than half a century. There was no one to visit. The city has been transformed greatly since she lived there, so I can’t even be sure I walked the streets where she once walked. Still, I’d glimpse grannies and think of her, reminded by something in their manner. And I couldn’t help but wonder what my life would be like if my family hadn’t left, if I’d been born and raised in China and not in America.

Family has a very definite weight in your stories. There’s always family tension, judgment, it tends to be something that makes the characters lie or run away. Is this an Asian thing? An Asian or a generational thing? Or both? Is it culture-specific, or not? Again and again, your characters take enormous risks to avoid shame.

It’s an Asian thing, a generational thing, sure, but perhaps more broadly, an immigrant thing. Immigrants risk so much and give up the familiar to build a new life in this country, which can be less than welcoming. I don’t know if my characters—the immigrants and children of immigrants—are always risking it all to avoid shame. They see it as a means of survival, to hold together their family and their identity.

Is it hard to find a good place to end your stories? How do you know your story’s done?

As the story gets rolling and the possibilities narrow (after I struggle with false turns and dead-ends), it leads to that “good place.” That place with the feeling or image or moment that resonates with what’s happened and what’s to come in the lives of the characters, even after the story ends.

As my book goes through production and makes its way into the world, I’ve found sentences I want to fix, or wonder if I should have taken a different approach in certain scenes. I’ve heard that some authors never read their first books again, except for the excerpts they use at readings. It pains them too much. After all they went through to get published, it still fell short of perfection, and maybe they feel they’ve evolved as a writer, or moved on from those kinds of stories. I’ve also heard of visual artists getting caught sneaking into museums, trying to fix their paintings. It’s hard to let go.

How many drafts would you say, on average, per story?

At least four or five, often more, and then I’d submit, and get rejected, submit and get rejected by literary magazines. I think the most was 20 times or more.

I don’t think I’ve abandoned a story for being too “out there.” I have a story that I started in college that I revisit every so often, for almost two decades, and though it has never cohered, I keep thinking I need to get back to it. Another story, which originally appeared in Calyx—a great journal of women’s writing—I decided not to include. I can’t remember specifically why, maybe I was concerned there were too many stories involving camping in the collection, or something about the character didn’t seem complete. Later, I had second thoughts.

Fortunately, the orphaned story will be part of a cool project later this year: the Short Story Advent Calendar, a collection of 24 short stories that readers will open day by day until Christmas. If I write another collection, I can include it. I have started more stories.

When did you first realize you could write “funny”?

Around friends and family, I’ve always been mischievous, but on the page, for years, I took a more serious tone (with some moments of humor.) A few years ago, I was reading The Water Margin: Outlaws of the Marsh, a classic Chinese novel, which is full of rogues and whores and picaresque characters. I started pushing myself to go further into the absurd. I’ve come to understand how comedy and tragedy can heighten each other, and deepen character.

As for other Asian American satirists, I loved Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan, YiShun Lai’s The Misadventures of Marty Wu, and Leland Cheuk’s The Misadventures of Sulliver Pong. I haven’t had a chance to read Jade Chang’s Wangs vs. The World, but I’ve heard it’s hilarious.

I think there’s a starlet who plays a minor role Kevin Kwan’s books, and I’d guess that there are fictional portrayals in Chinese language novels about that industry, but I’m not sure, either.

What are your current writing goals?

My forthcoming novel, A River of Stars, started as a short story that was published in ZYZZYVA. Eventually, I expanded it and it became the first chapter. I have three stories I started in the spring while I was at the Hedgebrook residency that I’d like to finish, a pile of books about the Cultural Revolution to read for my novel, and a timeline of events for my novel I have to tackle.

Finally, trick question: how did you know how to disable an airplane entertainment system? How did you know so much about the Beretta 92FS?

I’d been on a flight where the airplane entertainment system kept cutting out, and the system warns you not to touch while it reboots. To get more details on how it worked, I e-mailed a friend of the family who is a longtime stewardess—but she never responded! Perhaps she was concerned about revealing airline secrets. I was also worried about seeming sketchy if I lingered by the entertainment console panels inside a plane for too long when I was flying. I came across a sales site for those consoles, and I gathered enough information for the story.

As for the Beretta, I also searched out information online from law enforcement and gun sites. Long ago, a friend took me to a gun range because I scolded him for having a handgun. I have to admit, it was fun (yet terrifying) to shoot a gun. Such power. The shooter next to me was spraying a paper target at close range with a shotgun and I think he mentioned he was in the sheriff’s reserve. As a reporter, I also spent six weeks shadowing the Los Angeles Police Department. I gained a sense of why some people are attracted to law enforcement.

Over the years, I’ve hit up friends and acquaintances with expertise in medicine, law, and psychiatry and more with many questions—“what ifs” in the name of research.