Amid a national conversation about preschool and poverty, low-income New Yorkers are fighting for dignified welfare-to-work and and child care. But will they succeed?

July 8, 2013

From the outside, Luz Duran’s building looks quite unlike public housing: a newly mortared structure tucked among midtown Manhattan restaurants, theaters, and high-price rentals. Inside, the hallways are narrow, the small studios tightly arranged.

When I visited in late March, Duran’s shoebox-size apartment was dark. She hadn’t had power in two months, but there were no signs of disorder, save the unplugged refrigerator pulled out from the wall. A low partition separated the kitchen from the living area, taken up mostly by an elevated full-size bed.

Duran is round-waisted and 50 years old, with long eyelashes and dyed red hair tied in thin braids. Sitting on her leopard-print bedspread, facing my Spanish interpreter Telesh and me, she offered some fruit she had bought from a grocer 139 blocks away. “People don’t take food stamps in this area, so I had to go all the way to 181st Street to do my food shopping,” she explained in Spanish.

Thirty-two years ago, Duran left the Dominican Republic, where her 19-year-old son and ex-husband now live. “In my country there’s no work, there’s nothing,” she said of why she emigrated.

In the U.S., she has worked all over: from garment shops in New York City to a Tyson poultry plant in Mississippi. She had never been without a job until, in 2009, she finally left an abusive man in Miami and returned to New York for a fresh start. It was the first time she needed public assistance.

Welfare has kept Duran housed and fed, but she longs to work again. She had hoped the city’s Work Experience Program (WEP)—which, like the federal welfare law, prescribes simulated work activities—would provide schooling and training, or place her into steady employment.

Instead, she has apprenticed in a massive bureaucratic atelier. The city’s welfare-to-work programs have made her clean streets and staff a senior center, sit at a computer to scan job postings, and go around town collecting business cards from hair salons and other shops that have no intention of making a hire.

She showed me the stacks of documents from city agencies that have shaped her days and weeks. The letters arrive in English, which Duran reads poorly, so she has relied on bilingual friends to get the gist. Like others on public assistance, she has learned to navigate a constant slew of WEP assignments and baseless disciplinary notices.

When Duran first arrived in the U.S., the landscape was altogether different. “I came here for work in 1981. I worked a lot and would send money home to my family. There was so much work that you could leave one job and get another job right away.”

—

In New York and across the country, welfare recipients must earn their keep: by working off the combined value of their cash assistance, food stamps, and shelter allowance. These welfare-to-work, or “workfare,” requirements were legislated in 1996 as part of President Clinton’s vow to “end welfare as we know it”—or, as Joan Didion wrote sardonically, his attempt to hold “welfare queens and deadbeat dads” to the standards of “those who paid taxes and raised the kids and played by the rules.”

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) radically changed the structure of welfare. It cut access for childless adults and most lawful immigrants, set requirements for participation in simulated work and “job readiness,” promoted “diversion” policies that discourage new applicants, and instituted a five-year lifetime cap on federal benefits—though some states, like New York, provide beyond this. PRWORA also began distributing federal cash assistance through a rigid, state-by-state block grant called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Any apparent harshness in the law was tempered by a public-facing message of hard work and self-sufficiency. Americans stuck in grooves of dependency would be lifted out of poverty and set on an incline toward a new, middle-class life. The system would help them get back on their feet, less through temporary cash assistance and subsidized child care than through education, training, internships, and job-placement services.

But in practice the “work first” philosophy under TANF and PRWORA spawned a regime of unpaid labor, punitive discipline, and ineffective, ritualized “job search” performances. Many New Yorkers on public assistance are placed in random, dead-end positions unmatched to their skills and background.

Meanwhile, because they are forced to work, those with young children receive public child care subsidies—costly, precious resources that could go instead to working families living a smidgen above the poverty line. Workfare participants lose out both as workers and parents, despite the first express goal of TANF: “assisting needy families so that children can be cared for in their own homes.”

These are not new complaints, particularly in New York City, where, just after the ’96 reforms, then Mayor Rudolph Giuliani put some 40,000 welfare recipients to work in unpaid maintenance and clerical positions, alongside—and, some argue, in place of—city employees. Lawsuits and political feuds stretched into the early 2000s, but the general principle of working off one’s benefits was upheld.

Last July, welfare reprised its role as a political football. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a memorandum and guidance “encouraging states to consider new, more effective ways to meet the goals of TANF, particularly helping parents successfully prepare for, find, and retain employment.” It invited states to apply for TANF waivers to experiment with their work-activity programs, so long as they could meet strict quantitative goals.

“When we first saw this waiver, we were so excited,” said Don Friedman, a welfare rights attorney at the Empire Justice Center. “We thought, here’s the first welfare-related thing where they’re trying to do something positive.”

No sooner did the HHS memo circulate than presidential candidate-to-be Mitt Romney attacked it as “a plan to gut welfare reform by dropping work requirements.” (His statement was rated “Pants on Fire!” false by PolitiFact.) Never mind that Romney had been among the group of Republican governors that requested greater TANF flexibility in 2005.

The GOP-led backlash was fierce, and effective: not one state has applied for a waiver, and, as a spell against future tinkering, the House passed H.R. 890, a bill prohibiting any and all waivers relating to TANF work requirements. This restriction ultimately did not make it, however, into the Continuing Resolution reauthorizing TANF, signed into law on March 26.

Despite the uncertainty of it all, advocates in New York City and state are pushing officials to apply for a federal waiver and lobbying for other changes by statute. Their main goals: to make the “work” more meaningful in welfare-to-work and to redirect child care subsidies to assist the working poor.

—

Inside the East Harlem office of Community Voices Heard (CVH), a weathered sign features a photograph of an African-American woman hoeing a field next to a present-day welfare recipient picking up trash. Ask any CVH member who’s been through WEP, and they’ll recite the caption: “End Modern Day Slavery.”

Community Voices Heard, a grassroots non-profit group of low-income New Yorkers, is one of the last in the country organizing for dignified public assistance. Last September I began following its Welfare and Workforce Development committee, which seeks to preserve the safety net, raise the minimum wage—which New York just did—and eliminate unpaid labor.

According to City University of New York Professor Frances Fox Piven, author of Regulating the Poor, welfare organizing is all but gone. “For the last three decades, the abuse heaped on welfare recipients by leading political figures makes it harder to organize,” she explained. The stigma seems to have sunk in. “Organizing by welfare recipients almost always involves a sense of entitlement—people have to believe they have certain rights.”

Troy Canty believes that he and other WEP participants deserve better. A lifelong resident of Morningside Heights, he initially felt hopeful when assigned to clean subway cars at Grand Central Station. “I figured they were going to hire me. I was excited that maybe I could have this job; it was something to look forward to,” he said.

But Canty soon faced an alternating cycle of unpaid work and job-search placements, his benefits constantly threatened by petty infractions—alleged “failures to comply” (FTC) beyond his control and often lacking a basis in fact. “I stopped believing there’d be a job. I said to myself that they gonna keep FTC’ing. Everybody was getting FTC’d.”

Sitting on a leather couch in an imposing Columbia University building that houses vocational programs, Canty and I opened a letter from the city’s Office of Administrative Hearings. He was scheduled for yet another “fair hearing” to defend his right to public assistance before an administrative judge—but he didn’t know what he had failed to comply with.

Julie Wickware and her husband, Felix Cancel, who live in a Bronx one-bedroom with their seven-year-old daughter, are no strangers to this system. “Every time you get an FTC,” she told me, “they want you to start all over with orientation.”

For parents like Wickware and Cancel, each FTC means a new work assignment and a gap in child care; even if you later “win” your case, you’ll find yourself at a new work activity, having to scramble for a child care spot.

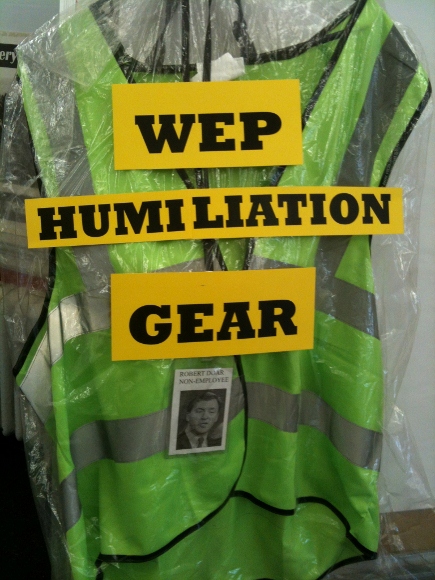

Welfare-to-work can vary significantly. New York City has dozens of different programs run primarily by private non-profits and schools. Depending on your luck, you could be assigned to anything from a subsidized job or skills-building program to an unpaid internship. You might plant sod in a park, do data entry, perform child care, surf the Internet for job postings, dispose of laboratory waste, hear a lecture on resumé-writing, or wipe down chrome in a subway station. You might wear a fluorescent vest or gather trash in a snowstorm; you might clean up vomit without gloves or a mask.

It’s the unpaid work, called “work experience” in the state’s Social Services Law, that CVH hopes to ban. The group has helped introduce a bill in the state legislature, sponsored by Assemblymen Keith Wright and Jeffrion Aubry and Senator Diane Savino, that would prohibit what too often looks like ordinary work but comes without a paycheck or a future.

CVH is also seeking reform at the city level—by putting welfare on the agenda of the mayoral candidates—and through the federal TANF waiver process—by trying to persuade the state’s Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance to apply. The agency would not comment on its view of the waiver opportunity.

Ann Valdez, a 46-year-old Coney Island native with curly hair and a deep Brooklyn accent, has received public assistance on and off since she turned 18, in the gaps between work and community college, while raising three children. (New York’s constitution mandates state-funded aid to the poor, called “safety net assistance,” beyond the five-year federal welfare limit.)

On welfare, Valdez’s assignments have ranged from fruitless, unpaid job-search stints to a decent, paid position in the city Comptroller’s office. It’s all a matter of luck: her sister, having been assigned to a subsidized public-sector job, managed to jump from welfare to a civil service career.

This kind of subsidized public employment recalls pre-1996 iterations of “work relief,” in which participants worked a low-wage job while continuing to draw some aid. In New York City, CVH has lobbied for more welfare-to-work slots in this vein, through partnerships with public-sector unions District Council 37 and Transport Workers Union Local 100.

Among the best subsidized employment options is the Parks Opportunity Program (POP). Last October, I visited Camelia Robinson toward the end of her six-month stint in POP, at River Run Park on the Upper West Side. She was earning $9.21 per hour, which counted toward Social Security. Her job was real, unlike WEP, she said, where “you’re not getting anything and working next to someone that is getting a paycheck.”

Most WEP participants live well below the “federal poverty level”—an outdated concept set at a mere $1,627.50 per month for a household of three. As Susan Antos of the Empire Justice Center explained, although this level is used to determine eligibility for some public goods, welfare cash assistance is “based upon whether your income is below the ‘standard of need,’ which is significantly below the poverty level in every New York county.” In New York City, the “standard of need” for a three-person family is set at only $789 per month.

As of December 2012, more than 581,000 New Yorkers were poor enough to qualify for cash assistance. This benefit, even when supplemented by food stamps, Medicaid, and housing assistance, permits only survival. “Welfare is a failure,” said Tim Casey of Legal Momentum. “Poor people don’t get the benefits they need, and TANF [the federal block grant that funds welfare] has a bad structure, a bad culture, and a bad history.”

Cash benefit levels are abysmal, and fewer families are being covered—even as the number of Medicaid and food stamp recipients increases. The Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies notes that, in 1996, before welfare reform and the TANF allocation system had taken effect, 68 percent of poor households with children were covered by cash assistance; by 2010, this figure had dropped to 27 percent.

In a weak economy, where even low-wage work is elusive, welfare becomes less a backstop and more a means of basic subsistence. The State Assembly concluded as much in 2006, well before the recession: “Without sufficient job opportunities available to welfare recipients, even the most determined individuals will not be able to achieve success in transitioning to self-sufficiency.”

—

There’s a fictive boundary between welfare recipients and the working class. Low-wage workers earn so little that they sometimes qualify for public benefits; those who don’t—especially those raising young children—are one illness, one blown-out tire away from the poverty line.

A full-time, minimum-wage worker in the U.S. earns less than $15,000 a year, below the poverty level for a single parent with two kids. But depending on where this family lives, they may not have access to cash assistance, public housing, or, critically, child care subsidies.

For Michelle, a single mother of two in Ossining, Westchester County, subsidized child care is the key to staying employed. At her steady but low-wage job in a dayhab for autistic and developmentally disabled clients, her hours are 7:30 a.m. to “anywhere between 4 and 5:30,” she said, “depending on what’s being demanded of me”—typical in the care sector.

Thanks to a public child care subsidy, Michelle, who asked that her full name not be used, pays just $65 per week, per child, for before- and after-school care at the Ossining Children’s Center (OCC), among the nation’s oldest, high-quality early educational facilities. Her two sons, ages 7 and 10, who have special needs and asthma, respectively, benefit greatly from the care at OCC. Without the subsidy, Michelle would have to leave her boys somewhere far less nurturing and safe.

A child care battle has raged in Westchester since 2010. The area used to be known for offering child care subsidies to families earning up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level, through a mix of federal, state, and local funds, as well as private donations; it’s now down to 200 percent, or $38,000 in annual income for a low-income family like Michelle’s. County Executive Robert Astorino had also sought to increase the family contribution, or co-pay, from a historic level of 10 to 15 percent, to 35.

“I have not one but two kids, and when you’re raising the co-pay, that becomes unaffordable,” Michelle said. “With all these cuts, you force parents back on welfare, whereas before you had them out there working. You’re saying ‘your good is not good enough.’”

Co-pays and waiting lists have grown, and eligibility criteria tightened, with cuts made to public child care budgets. As with the TANF welfare system, the federal government funds child care subsidies through a giant block grant on a state-by-state basis. Federal regulations require states to spend this money first on welfare-to-work participants—too often enabling dead-end job activities—and then on low-income families earning up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level. (States and counties can provide on top of that, as Westchester has historically, if they have the resources).

Child care subsidies are so critical and in such high demand, yet so underfunded, that states routinely use TANF and other social services funds to create child care slots—robbing a pauper to feed a beggar. In 2012, at least 23 states had waiting lists or froze intake for child care assistance, according to the National Women’s Law Center.

To free up child care money for the working poor, 25 states exempt parents and guardians receiving welfare from doing work activities if they have a child under the age of one. (Of these, Vermont, Washington, and California have more generous rules.) Such policies prioritize resources for parents with real jobs over welfare-to-work participants going through the motions of a “work activity.”

Senator Savino has sponsored several child care-related bills in the state legislature, including one, introduced last year, to bring New York in line with these other 25 states. The bill was recently reintroduced in both the Assembly and the Senate.

“We really pushed hard last year but faced philosophical opposition, particularly from the city of New York,” Savino said, referring specifically to Robert Doar, commissioner of the Human Resources Administration (HRA), which oversees city welfare programs.

HRA would not comment on either the pending child care or anti-WEP bills, but emphasized the centrality of its “Work First approach” for all aid recipients, including new parents: “The most defining element of HRA’s Cash Assistance program is the very rigorous work requirement… Through our Work First approach, which encourages quick engagement to the workforce supplemented by training and education, … [i]n 2012, HRA helped place a total of 86,947.”

According to Savino, “People think [a parental exemption] undermines the success of the welfare reform model—but we have limited resources now, and subsidized daycare should be available for working women who have managed to claw their way into jobs.”

Savino reported a lack of support from the women’s rights community. “Women’s organizations are missing a real opportunity here” she said. “It’s not just about reproductive rights and paid sick days.”

She hopes to force child care for low-income women onto Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Women’s Equality Agenda. At present, there is no mention of it in his gender platform, despite the fact that nearly 234,000 children in New York depended on subsidized care last year.

Safe, high-quality child care is more than a work support: it prevents child abuse and neglect, according to Billye Jones-Mulraine, director of Kingsbridge Heights Community Center (KHCC) in the northwest Bronx. “You want quality child care with somebody who’s licensed, who has materials, and is very protective of children, particularly for late night or overtime shifts,” she said.

KHCC, like the Ossining Children’s Center (OCC), provides care on par with facilities in far-wealthier neighborhoods. But, says Howard Milbert, OCC’s director, “So many families have been cut out of the program. At the same time, New York state is looking to improve the quality of its daycare. Unless there’s some support for salaries in the field and for centers, the working poor are just not going to be served.”

Due to budget concerns, Suffolk County on nearby Long Island has reduced eligibility for child care subsidies from 275 to 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Subsidized child care now goes more to parents on welfare, “so it’s not really meeting the needs of those who are low-income workers,” said Brian Lahiff, assistant director of the Child Care Council of Suffolk, Inc. “The idea of transitioning people into self-sustainability is not happening. They’re not getting the assistance they need.”

Although their daily lives unfold far from Washington, New York’s working poor are tracking national policies. There are opportunities to reform workfare, via the TANF waiver; there are cuts due to the federal sequester, including the loss of 70,000 Head Start slots; and then there’s President Obama’s early learning proposal, which would theoretically expand preschool access for needy families.

“The situation nationally is so contradictory,” said Kathy Halas, director of the Child Care Council of Westchester, Inc. “On the one hand, the administration is talking about early learning in a way I’ve never heard in my decades on the planet; and then there’s nothing in the budget. In general I think it’s going in the right direction. I just don’t know if there will be money.”

—

Lack of funding is a permanent feature of aid to the American poor. But existing funds are too often squandered: child care subsidies on unpaid workfare participants—and welfare funds on simulated work activities instead of training, education, and transitional employment.

It’s the false promise of real, lasting work that deflated Luz Duran. She looked stricken as we sat in her apartment, sifting through bills. My Spanish interpreter and I helped decipher a letter from her landlord demanding $353.50 in unpaid rent and threatening eviction.

“What day is it today?” she asked. The arrears were due in exactly a week.

Duran’s latest WEP assignment had her working sanitation three days a week, on the edge of the Hudson River near 14th Street. The other two days, she had to attend job search—“They just have you sitting in chairs,” she said.

In her continuing effort to find paid work, she was waiting for a drug test to clear: the first step in applying for work as a home health attendant. I asked if the welfare program had provided any help. She intoned a string of “no”s and brought out two certificates documenting her training as a personal care and home health aide.

“I paid $400 for this one. I paid $300 for that one. Welfare didn’t want to pay for it, and since I want to get out of this program, I paid for it myself.”

She had tried other things, too, like collecting recycling and selling bottled water on the street. But, lacking a license, her brief street-vending foray landed her in jail and produced a domino effect: she had to appear in criminal court, which froze her citizenship process and prevented her from showing up for WEP, which meant sanctions and a cut-off in benefits.

Duran is the only person I know who waxes nostalgic about poultry processing work. Years ago, she’d been a “breaster” 80 hours per week at a Tyson plant in Mississippi.

“When I was working at Tyson, I earned $9 per hour. I had everything—health insurance, vacation,” she said, but back pain eventually forced her to quit.

She didn’t mind her latest WEP assignment, in sanitation, except that it was unpaid.

“If they pay me, of course I’d stay, but I asked the supervisor, and they said they’re not hiring. If you hear of any home attendant jobs, please call me.”

Research and writing generously supported by the Ms. Foundation for Women Fellowship and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Spanish interpretation provided by Telesh Lopez of the Caracol Interpreters Cooperative and Kristina Marie Fullerton.