‘Wanting privacy in a police state was sheer stupidity’—to tell the stories of her family in China without the threat of censorship, Yang Huang had to look beyond Mandarin.

August 22, 2016

The Three Dialects

By age seven, I had lived with my grandparents and parents in two cities and spoken three different dialects. My earliest memory of language was the Wenzhou dialect that my paternal grandparents had spoken in a farming and fishing village in Zhejiang province. On the streets of Shanghai teeming with elegant people, my grandparents, uncles, and aunt would burst out into the Wenzhou dialect to prevent bystanders from eavesdropping on their conversation. I had a limited vocabulary. Even after having lived in the States for decades, a few words in the Wenzhou dialect bring back a rush of memories of my family and the boundless love that they lavished on me during my childhood. Although I have only visited the seaside village twice, I know I come from a clan of farmers and fishermen.

In daycare I learned Shanghainese. To me, it was akin to a dialect of the nobility. My parents worked and lived in Jiangsu province. I had lived with my grandparents’ family in Shanghai since I was 10 months old, blissfully unaware that my resident card was in Jiangsu province with my parents, who I didn’t really know. My grandma used to joke with me that the gas bill pinned above the sooty stove was my residence card in Shanghai, which would allow me to enroll in a neighborhood school. Alas, my dream was shattered when I had to return to my parents’ home in Jiangsu province to begin elementary school. I must have experienced a cultural shock when I learned the Yangzhou dialect, which sounded coarse and foreign, an archetypal redneck dialect, to the delicate ears of Shanghainese.

I picked up the dialect effortlessly but found it difficult to say the words “Mom” and “Dad.” My mother had fallen ill and sent me to my grandparents’ house when I was ten months old. I had only a few visits from my father during the seven years, while my mother had been busy with her job and with raising a son. It was common for Chinese families to enlist their parents’ support in childrearing, but it took its toll. I wasn’t able to say “Dad” until a month after my return. Another month passed before I could say “Mom.” My mother had resisted the burgeoning one-child policy to give birth to my brother in 1972. As a penalty, my brother couldn’t get his residence card or food ration for three years after his birth. The hard-won son was their hope to carry on the family name. Who was I to argue when he munched on a juicy apple? If I begged, I might get a shriveled tangerine.

Thus I was fluent in three dialects, each associated with a time period, a different set of caretakers, and distinct emotions and challenges. My experiences were not unique. If anything they were a proof of my ordinary existence during a time of momentous change in China. The terror and suffering in the Cultural Revolution culminated in the outpouring of grief over Chairman Mao’s passing. In 1976 children of all ages, myself included, wore black armbands and took deep bows at Mao’s portrait, paying tribute to China’s savior. The despair on millions of sobbing faces was a spellbinding scene that became an embarrassing cliché a decade later.

(Not) Writing in Mandarin

In elementary school, speaking in Mandarin, the official dialect, freed me from the three dialects that had made up my life experiences. As a child I learned to speak only the tip of the iceberg in order to be circumspect. These tacit rules intimidated me. Mandarin gave me a sort of anonymity, a license to speak my mind without the burden to be always polite and female. I dropped the dialects and used only Mandarin in intellectual conversations. As I grew older, writing became a revelation. My pen spilled out words I didn’t speak and divulged emotions that could make me cringe. I took to writing like a marathon runner lured by the distance.

I kept a journal in middle school. During recess I only had time to write poems, an outpouring of raw emotions in childish rhymes. Within a week, my then best friend pilfered my scribbled poems and shared them with a boy. They had a good giggle at my expense.

The boy asked me, “Don’t you like your brother?”

His face, mild and kindly, had pity for me. At age twelve I felt as if I were stripped naked in public. There was no safety at home, either. My brother read my diary. I swore never to write poetry again. Wanting privacy in a police state was sheer stupidity. To be spared of betrayals, I silenced my complaints.

Still, my parents were apprehensive about my scribbling. My father painted a bleak picture of someone who had to live by her wits. “There is danger in becoming radicalized,” he said.

In the Cultural Revolution, he had complained about the prevalent political prosecution. “There ought to be moderation,” he had said. He’d been exiled to a small town, where he met my mother. The happy family life was the saving grace. Many writers and intellectuals were not so fortunate. Lao She, rumored to be a front-runner for the Nobel Prize in Literature, had suffered beatings and humiliations at the hands of Red Guards. He later committed suicide by drowning himself in Beijing’s Taiping Lake.

My father was determined to shield me from political prosecution. He encouraged me to pursue science and technology instead. “Nobody can touch you, because knowledge is power.”

I was good at math. But more importantly, I was a good daughter who wanted to make her parents proud. So I studied physics and computer science, reveling in the abstract equations and computer codes. Having failed to write poetry or keep a journal, I was persuaded that writing was impractical as a career choice.

Writing like a Foreigner

I began to study English seriously in middle school. The reading included texts like “The people’s communes are good.” English was like another dialect in alphabets. By then, I had read enough Chinese novels to recognize the thinly disguised political propaganda, such as how communist heroes overpower lascivious bandits in Tracks in the Snowy Forest, or the scar literature that protested the Cultural Revolution, including the works of Wang Anyi and Zhang Xianliang. These genres made me feel claustrophobic: the former was predictable, while the latter made me feel powerless.

There emerged avant-garde writers using an arsenal of literary devices to tell larger-than-life stories in allegory, hyperbole, metaphor, satire, symbol, euphemism: Bei Dao, a “Misty” poet, and Gao Xingjian, a pioneer of absurdist drama who later won the Nobel Prize, both pushed the boundaries and ended up being exiled from China for the political overtones in their work. I admired their early works but found some texts hard to decipher. As an engineering student, I was logical and levelheaded, not nearly as excitable as my schoolmates majoring in humanities. I needed some other style to inspire me and free my imagination.

In the library I discovered the translated novels by Victor Hugo, Alexander Dumas, and Balzac. I discovered the new heights of emotion and hope that fiction could make a teenager feel. French writers didn’t have to negotiate with censorship the way Chinese writers did. Reading Les Misérables, I was shaken by the passion and folly of the French Revolution. I went on to read translated works by Russian, British, and American novelists. They introduced me to direct expressions for human experiences that struck a chord with me. I studied their word choices, emotional nuisances, and close personal narratives that defied the self-censorship entrenched in my upbringing.

Even the literature by authors from Taiwan and Hong Kong were bold and refreshingly personal and honest. In 2011, popular novelist Murong Xuecun blamed the mainland’s literary censorship for quashing writers’ creativity and sabotaging the Chinese language. A majority of writers in mainland China were held in contempt, “because [they were] already castrated while still in the nursery.”

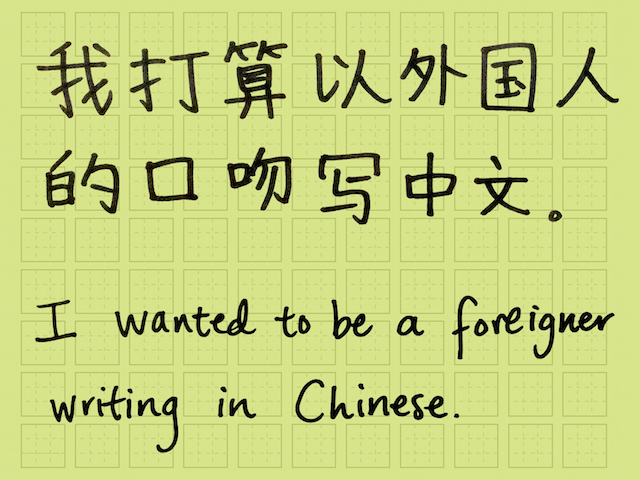

As a teenager in the 1980s, I was angry with my inability to use Mandarin to achieve the supple and fearsome effects that foreign writers did in their works. I rebelled against the pretentious writing in Mandarin. I stripped away adjectives and broke down my sentences, as an attempt to mimic the translated works that I admired and aspired to write. My teacher often asked me to “smooth out” the prose, but I flexed my muscle by striving for new perspectives and experiences. I wanted to be a foreigner writing in Chinese, to be freed from clichés and preconceptions and see the world with fresh eyes.

My Mid-Twenties Crisis

I arrived in the U.S. as a 19-year-old engineering student. Immediately, I set out to relearn English: my accent, vocabulary, and even the emotions I used. I was speaking a different tongue from the native speakers. The “Chinglish” I learned was more formal, without emotion, and often dishonest. Translating Chinese euphemisms into English was a waste of time. Using plain, factual words was more than a reeducation; I was to be stripped of my pretenses and reborn into a new culture.

I lived in the dorm and immersed myself in an English-speaking environment. I’m always helpless with grammar, in Chinese or English. To me, grammar is a crutch or an afterthought in learning a language. I decided to approach English like a child learning a new dialect. Every day I listened to the phrases and sentences and tried to memorize them verbatim. I forbade myself from inventing “Chinglish” in order to get by. Initially I was slower than my Chinese friends. Sometimes I looked so perplexed that my friend prompted me to speak Chinglish, but I was stubborn. I dove into the dictionary for sheer enjoyment.

I scored A’s in the engineering courses to compensate for the B’s in the humanities. My roommate, a Jamaican girl raised by a single mother, was the first black person with whom I had close contact. She was at times mischievous and inquisitive.

One day she complained, “Do you ever speak up for yourself?” and stopped short of pinching her eyelids to make slanted eyes.

“You know nothing about me.” I glared at her. “I’m not so quiet in China.”

She was so surprised by my outburst, it was as if she saw me for the first time. From then on we were friends.

She shared with me her Christian faith. I was puzzled that she, an engineering student, could be “superstitious.” We enjoyed each other’s company and quirks. At age 20 we both had our insecurities. I considered her “American,” because she spoke good English. She thought of me as “white” and “rich.”

It took me decades to realize that “white” was more than a skin color. In China, I belonged to the majority race and to the middle class. I was “white” in China and brought my pride to the U.S. Even when I had only $0.87 left in my checking account, I could get a student loan from my relatives, because “Knowledge is power.” My technical skills earned me a job despite my limited English. My roommate saw through my quiet exterior and recognized a middle-class person: hence “white” and “rich.”

After working a technical job for two years, I paid off my student loans. For the first time I had an apartment, so spacious I could hear the echo of my heartbeat. After every workday a new silence filled my life. So I had a midlife crisis at age 23. I went to a local church but I didn’t feel that I fit in with the white families there. I wasn’t just a computer engineer with a Chinese face. Deep down I was a person who had come from a clan of farmers and fishermen in a Chinese village. At church, the preaching wore on my nerves and gave me a headache. I remembered the madness of how China had worshiped Chairman Mao as the country’s savior.

An Immigrant Writer

Finally I came clean with my need to write. My Chinese friends were shocked: What possessed you to write in English? At the time Chinese memoirs and self-help books by expats were in hot demand. I could write in Chinese and reach an enormous audience. There was a bestselling memoir, Manhattan’s China Lady, about a divorced woman who starts a new life in America, marries a handsome white man, and has a gorgeous mixed-raced son. It might be obnoxious of me to critique a real life story, but I found the Cinderella story insipid and dishonest.

To me, telling a rags-to-riches immigration story was a way of saying, “Look: Here I am, and there you are.” My parents would have approved of me, and my old friends might be envious—all the more reason for me not to do it. I hadn’t come to the States just to live a “white” life; in fact, I could do so in China. I was a dreamer who wanted to challenge the status quo. In the States, I wanted to live a full life and claim the identity of a woman, an Asian, and an immigrant writer.

Now and then I tested writing in Chinese. Using English changed the way I wrote in Chinese. My prose became bolder, more direct, and even a bit masculine. I blogged on a site in mainland China, using metaphor, satire, allusion, and homophones in order to elude censorship. It was a race with a powerful enemy: the culture that had nurtured me. I could not transcend it. My article containing “sensitive” words was deleted within a day. I befriended other bloggers, who applauded my honesty and freethinking. Finally, I could write in Chinese with a foreigner’s objectivity, but I wanted more.

Writing in English, I could tell the stories of destitute people and social injustices, a subject matter I was not able to fully explore in Chinese. My emotional bond with my grandparents transported me to the impoverished seaside village. My tall illiterate grandma used to bustle from dawn to dusk, cooking and sewing, caring for children and elderly in-laws, feeding pigs and chickens, making rice cakes and dumplings, gutting and scaling fish, cleaning and preserving crabs. Her reticence haunted me, so I was compelled to tell the peasants’ stories. If Mandarin was my middle-class dialect, then English became my working-class language. Writing in English was both harder and easier than I had imagined. Easier because I didn’t carry the baggage, self-censorship, and cynicism. Harder because it was a foreign language, and I struggled to master it and find an audience.

I went back to school to study English and American literatures. I read Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Theodore Dreiser, Ernest Hemingway, Toni Morrison, Willa Cather, and Zora Neale Hurston, to name a few. I had read some of the books in translation before. As an aspiring writer, I discovered new insights rereading them in English. I learned how hard work and destitution could breed a noble and indomitable spirit. The theme of women’s work running through Austen’s novels didn’t show submission or fatalism but rather virtue, courage, and self-worth. Surely I could emulate the masters to give my fictional characters a chance at a better life that was deprived of them in the real world.

I encountered some unforeseen obstacles. I once wrote a personal essay about China. My teacher, a middle-aged white man, praised my essay in the class. I was encouraged. When I wrote about China in another essay, he felt he had to put his foot down and teach me a lesson.

He called me out in front of the class. “Another piece about China?” He forced a half smile. “What’s up with you? Are you homesick?”

I was too stunned to reply. In my mind I finished his thought, “Snap out of it!”

Perhaps my immigrant narrative invaded his white territory of dominance. In that sense, I could not prove my worth. I had to be careful and bide my time. Later, a physics professor told me that Joseph Conrad was the only author who wrote in his second language. His condescending smile only gave me minor annoyance. I learned to protect my ambition from the casual rejections. Time was on my side. In 20 years I could develop into a writer, after the professors had forgotten their dismissive words. So I staged my strongest protest: Silence.

I guard my writing time jealously. In my daily life, I am organized, reliable, and conscientious. I have to keep hundreds of computers running properly and cannot be one minute late to pick up my children from school.

My persona changes when I retreat into my writing life. On the weekend, I ignore the dirty dishes in the sink. I ask my husband to bring our boys to their baseball practices, so I can enjoy my lap swim and then sit down to write. If my goal is 30 laps, I usually go to 31 or 32 laps. This is a reminder that whatever my goal is, I always do a little extra, not something to show off, but a habit, a promise I keep between me and my work, that I can push beyond my physical limits every time I use my body or mind.

After living in the United States for 26 years, I rarely concern myself with not being a native speaker anymore. For one thing, I cannot imagine myself speaking one language, only one dialect, and living in the same community my entire life. I would be a different writer, not necessarily a better one. Since I’m used to writing realistic fiction in English, I can write in Chinese with the same discipline and passion. When I blogged in Chinese, I found myself conceiving a story in English and then translating it into Mandarin.

One cannot choose her parents or home country. But she can be married into another culture, a second language, and a new career. I’m grateful to have adopted English as my first language to write realistic fiction. Writing is a beautiful privilege. I often feel tired and overworked until I sit down at my writing desk. Then I shed my polite mask, tear off the layers of complacency, prejudice, and hypocrisy, to reach deep inside and feel the beating of my own heart, discover who I am and what I believe in, and then pour my soul into the characters and their stories.

My grandparents sat in the front row. My brother wanted to run away, so my grandma put him on her lap and held his hand. I was the good girl, furtively playing with my coat and exploring my pocket. Photo courtesy the author.