How an Asian American literary pioneer fell into obscurity

September 7, 2022

The first celebrated Korean American author, Younghill Kang 강용흘, 姜龍訖 (~1903–1972), believed only literature told the whole truth, and that it was the most permanent of the arts. “We were in Berlin when Hitler burned the books, but those cannot be destroyed,” said Kang to the New York City Post on October 2, 1937, while he was promoting his novel East Goes West. “In 221 B.C., a foreigner, Shi Huang Ti, conquered China and his first aim was to destroy all books. Two thousand scholars were buried alive, the aim being to leave people with the idea that he was their first emperor. A few years later some scholars who miraculously escaped set to work and from memory restored all the classical literature that had been destroyed,” he said. Eight decades since Kang gave that interview, East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee (1937), his original, hilarious, and irrepressible novel, has become a Penguin Classic. Yet his first novel, The Grass Roof (1931), remains out of print.

Between Kang’s first publications and his canonization today is a complicated story shadowed by politics. Considered “the father of Asian American literature,” Kang, ever visionary, understood that questions of power and race shape literary history. He set his sights higher—nothing less than “the immortality of the soul,” in his own words. The soul? He rubbed shoulders with the Lost Generation—bereft after the devastation of the First World War—the likes of modernists F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe in Manhattan. “Tom” was Kang’s closest friend. A fellow NYU professor, Wolfe introduced Kang to Scribner’s legendary editor, Maxwell Perkins, and the rest became history: Perkins acquired Kang’s first book. Kang and his poet-wife, Frances Stacy Keely (1903–1970), established themselves within New York City’s intellectual elite in the 1930s, living amongst bohemians and the “unchurched” in a building owned by the nearby St. Marks Church in-the-Bowery.

Dizzying international success came with Kang’s English debut, The Grass Roof. This first book “treated of the Orient,” he informed Yaddo in his project proposal for a second book he was undertaking in 1932. The Grass Roof introduces his fictional alter ego, Chungpa Han, as a single-minded, precocious child who treks to Seoul then Tokyo to further his education, looking to the West as the future. It is a story of the artist as a young man in rural Korea and the disappearance of the old ways due to Japan’s colonization. Praised effusively by British writers Rebecca West and H. G. Wells, The Grass Roof was translated into German, French, and Czech, and even became assigned reading for American GIs in Korea.

Kang left New York City for Berlin as the first Asian person to win a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. With wife and baby daughter Lucy Lynn in tow, they traveled through Rome, Berlin, Munich, and Paris from 1933 to 1935 while Kang worked on his second book that would “treat of Orientals in America.”

While the family lived in Europe, rabid fascism spread. Total war mobilization began in Kang’s native Korea, annexed into a Japanese colony in 1910. Kang wrote in correspondence, “In Germany I was more popular than the high-nosed American in the Hitler thirties, because I could be mistaken for a Japanese, the only race descended from the gods outside of the Aryans.” Ironic. In Korea, the Japanese government attempted to obliterate all vestiges of Korean identity, especially language and customs, and substituted Japanese for Korean family names. With paper and ink, Korean scholars, journalists, and artists tried to articulate how the future, their futures, seemed to disappear. (One episode in The Grass Roof portrays the excitement and tension of Korea’s March First Independence Movement, a mass, peaceful demonstration against Imperial Japan.) The intellectuals wrote not only in Korean but in Russian, Japanese, Chinese, and English and organized in Vladivostok, Tokyo, Shanghai, Hawaii, and D.C for national independence. And luckily for me, Kang wrote vividly in my dominant language, English.

I came to Younghill Kang’s words in my thirties through the Penguin Classic paperback of East Goes West published in 2019. After researching colonial Korea for my academic work, drawn to the possibilities and quagmires of a time before ideology split Korea into two nations, I read his lively New York novel with delight during 2020. The story is also told by Kang’s alter ego, the starry-eyed Chungpa Han, who comes to New York City with only four dollars to his name and a suitcase full of Shakespeare. East Goes West perfectly captures New York City’s glorious chaos, “the vast mechanical incubator of me.” In Han, I saw my grandfather and myself. Western science, mechanization, and efficiency collides with his deeply impractical dreams as a literary wanderer steeped in classical Chinese, Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist learning as well as the English canon. Hijinks ensue: Han takes on diverse jobs to survive—domestic work, factory work, farming, department store sales, selling Bibles—along the Eastern Seaboard. New York City, his adopted birthplace, is both frightening and thrilling. It’s rare to find a novel so alive, astute, funny, and poetic. I searched for so long. So why did I find Kang so late? Why did he become lost from public view?

Before East Goes West

Before it became East Goes West, Younghill Kang called his second novel “Death of an Exile.” Editor Maxwell Perkins and friend Thomas Wolfe suggested cheerier titles, such as “The Americanizing of Younghill Kang,” “Rebirth in America,” and “Yankee Out of Korea.” But “Death of an Exile” referred literally to one of the novel’s central characters, To Wan Kim, a heartsick Korean poet-scholar who lives in Greenwich Village. A product of a lost era and land, Kim dies alone. He serves as a foil to the idealistic Chungpa Han, who has a foreboding dream of his own death by fire. This was the second, symbolic meaning of the title, what Kang called, “the rebirth in the soul of the hero.”

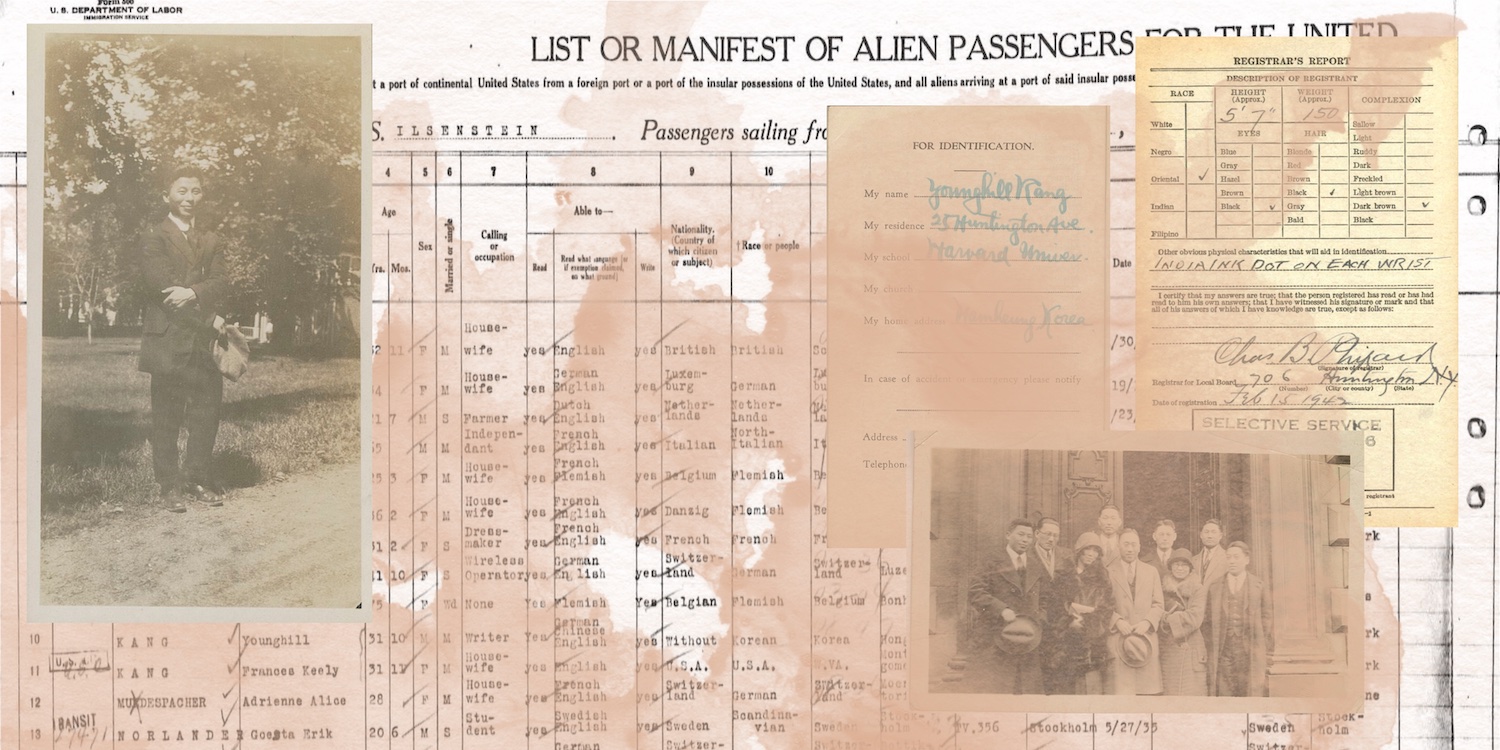

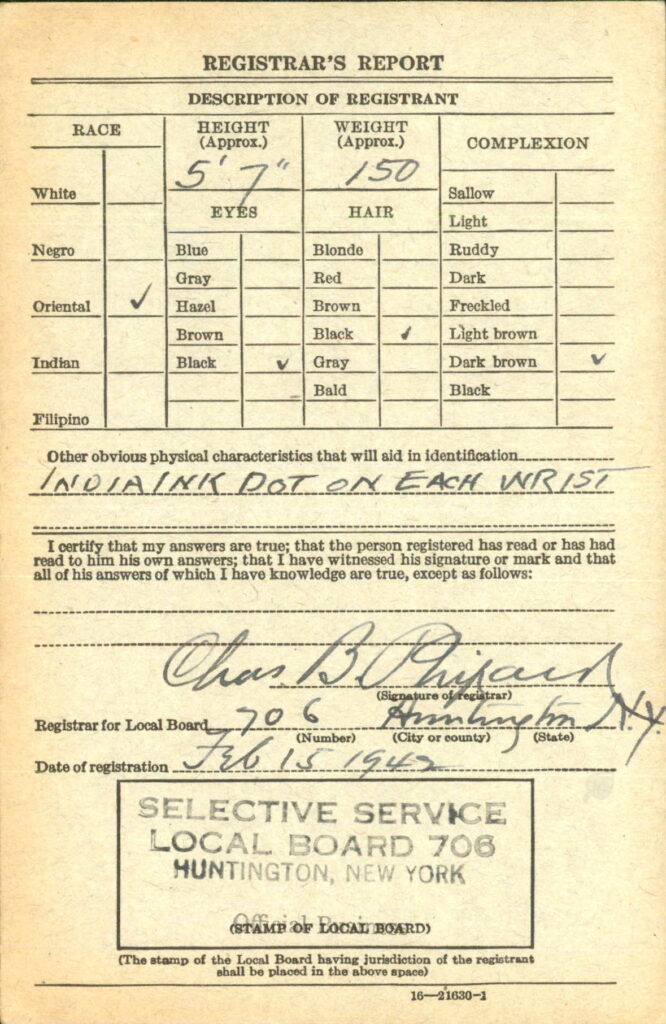

And Kang firmly believed himself “the hero,” if his first autobiographical novel, The Grass Roof, is any indication. Early in that first book, he describes a playful scene where a young Chungpa Han and his two best friends take thread and needle to their little wrists. “We are here to take binding vows,” Han says, “to be the three greatest men in the country.” He recants, “Not in the country, but in the whole world.” Like Chungpa Han, Kang wore a tattoo on each wrist—a black dot of Chinese ink—noted by immigration officers. “The sign which I still carry and shall have to carry for life,” wrote Kang, spoke to his lofty childhood ambitions.

Citizenship Precarity

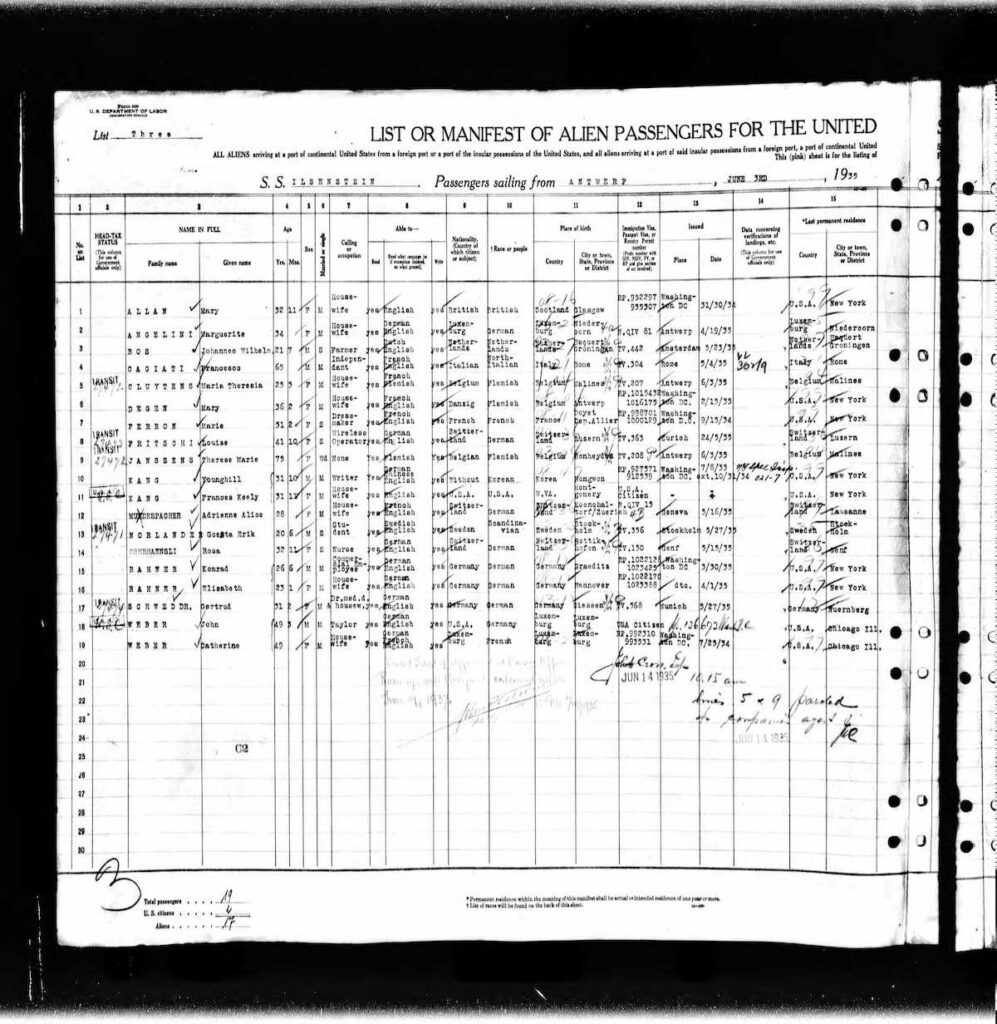

To be fair, Younghill Kang’s entry, let alone success, into the United States was an incredible feat. The Grass Roof makes that clear. Sponsored by Christian missionaries, Kang squeaked into the country just three years before President Coolidge’s Immigration Act of 1924 banned Korean and East Asian immigrants for nearly thirty years. He was ineligible for citizenship because of his race. Although interracial marriage was illegal, he married Frances Stacy Keely, a white, West Virginian woman of Irish descent in 1929. She lost her citizenship due to their marriage. Keely, a Wellesley graduate, shared a love for poetry and literature with Kang. (In the time-honored tradition of literary men who benefit from their wives’ labors, Keely served as Kang’s typist and first editor.) They stayed together at the Yaddo retreat for artists in August and September 1932 to work on East Goes West, which led to him receiving the Guggenheim Fellowship (his second try). Keely successfully petitioned for her citizenship in 1933 before sailing with Kang to Europe.

Unlike his wife, Kang was a man without a country for over three decades. He made citizenship bids to the U.S. Congress at the height of his literary career in 1939. Both bills were rejected. He only naturalized in 1952 with the passage of Immigration Act Amendments. Some of the most bittersweet archival documents are Kang’s immigration records. In his return trip from Antwerp to New York for his Guggenheim, under “Nationality,” among the Belgians, Germans, Americans, and Swiss, he is the only one listed “Without.”

The Mystery of Younghill Kang’s Decline

During the Second World War, Younghill Kang’s publisher, Scribner’s, stopped printing his books due to paper shortages and, one presumes, a lack of interest. (Later, his translation of poet Young-un Han’s Meditations of the Lover anda third novel, “Dragon Awakened,”were rejected by Scribner’s, too.) In 1959, the publisher Follett reprinted Kang’s debut, The Grass Roof. The publication meant Kang could go back on the road again, promoting the novel and lecturing on the Far East. He spoke, for example, with the Chicago radio legend and oral historian Studs Terkel.

To scrape together a living, Kang crisscrossed the continental United States in his car. He delivered spellbinding lectures in libraries, casinos, and churches. In his 2020 NYRB article, Ed Park describes how two strange sheets of paper that advertised Kang’s lectures fell out of his copy of The Grass Roof: the first advertisement orderly and professional, the second, “a shocking composition,” “the snapshot of a meltdown: a blizzard of text, in a dozen conflicting typefaces and angles, comprising shards of testimonials and invitations (‘LUNCHEON IN ALEXANDER DINING HALL’). It’s hard to know what’s being offered. The word ‘Vietnam’ ominously appears, unattached; then the eye makes out the tiny words ‘Or Negotiation?’” Local newspaper listings from Indiana to Texas show Kang’s frantic energy and jaw-dropping range. Given that he gained national acclaim in the 1930s and even worked for the nation during the 1940s, his steep decline in the 1950s and the 1960s seems especially tragic. “This feels like a higher order of defeat,” writes Ed Park.

Some have volunteered reasons for the decline of Kang’s fortunes, namely his misplaced faith that he might be the Asian exception to the racist rule of the United States or PTSD from the wars he did not fight but felt. But to me, Alexander Chee, in his foreword to the Penguin Classics edition of East Goes West, strikes at the heart of it: “the experience of seeing the country and culture you were born into destroyed, and of everything you loved seeming powerless in the face of this destruction.” In another word, war. Both of Kang’s sons were military men. His eldest, Christopher (Younghill C.K. Kang, born in 1937), was a major in the United States Air Force, and his youngest Robert Kang (born circa 1949) was a marine. They followed in their father’s footsteps. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Younghill Kang had volunteered to work for the U.S. War Department as “Chief of Publications” stationed in Korea. But their patriotism ultimately mattered little. As historian Erika Lee writes in The Making of Asian America, “the lines between [Good Asian Americans] and [Bad Asian Americans], however, were not always clear and could shift without warning.”

Anti-communist purges stretched from East to West. In his foreword to Bong-youn Choy’s Korea: A History (1971), published one year before his death, Kang wrote about the life-altering decisions by the U.S. military to prop up Syngman Rhee, the South Korean dictator, in the aftermath of the Second World War. “In those days, ‘not a communist, no, but an anti-Rhee man’ was a damning indictment even in America,” Kang wrote. Rhee’s rule, which lasted from 1948 to 1960, was the capitalist bulwark to Kim Il Sung’s communist one. The Rhee regime is now remembered for its police brutality, student uprisings, rigged elections, and suppressed free speech. Opposing Rhee, even in the United States, amounted to communist sympathizing.

In the United States, anti-communist paranoia against the Chinese and other East Asians ran rampant, and teacher denunciations occurred everywhere, including New York City. Kang wrote codedly in 1971, “The rule of Syngman Rhee lasted in Korea only twelve years. But it was long enough to ruin the careers of many Koreans in America for life.” According to poet Walter K. Lew, who interviewed Kang’s three children in the 1990s, Christopher, Kang’s elder son, accompanied Lew to the archive, pointed at a photograph, and said: “There’s that bastard at NYU who said my dad was a communist and ruined our lives.” Thousands of New York City public school teachers and professors were interrogated and dismissed from their jobs in the anti-communist purges of the 1950s. Some were actually communist, and some would desert the party. Documents from the Cold War era are still being released today. Further, careful research into the anti-communist purges impact on Asian Americans like Kang is sorely needed.

Kang passed away in Florida in December 1972, two years after his wife Frances Keely died, and it’s unclear where he was cremated or buried. More than a decade later, the Long Island Forum magazine writer Alonzo Gibbs remembered Kang as an old friend and local with fondness:

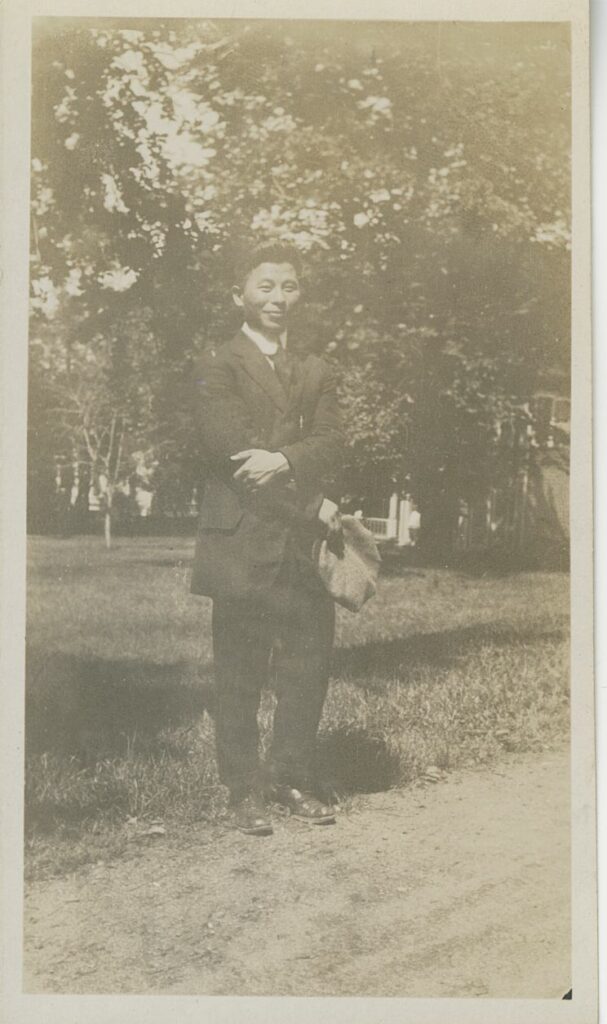

I have only to glance up at a picture . . . to see him again, so short and muscular, with a round sensitive face and empathetic eyes . . . All I can recall of his height is that when he became passionate in argument, he would rise on tiptoe to emphasize some truth he saw clearly and was afraid others had missed.

What truths have we missed? Kang was a metaphysical poet thrust into the Machine Age and crushed by the Cold War. How much has changed? “For in me has always burned this Taoistic belief in the continuity of living and of time,” wrote Kang in East Goes West.

What Remains

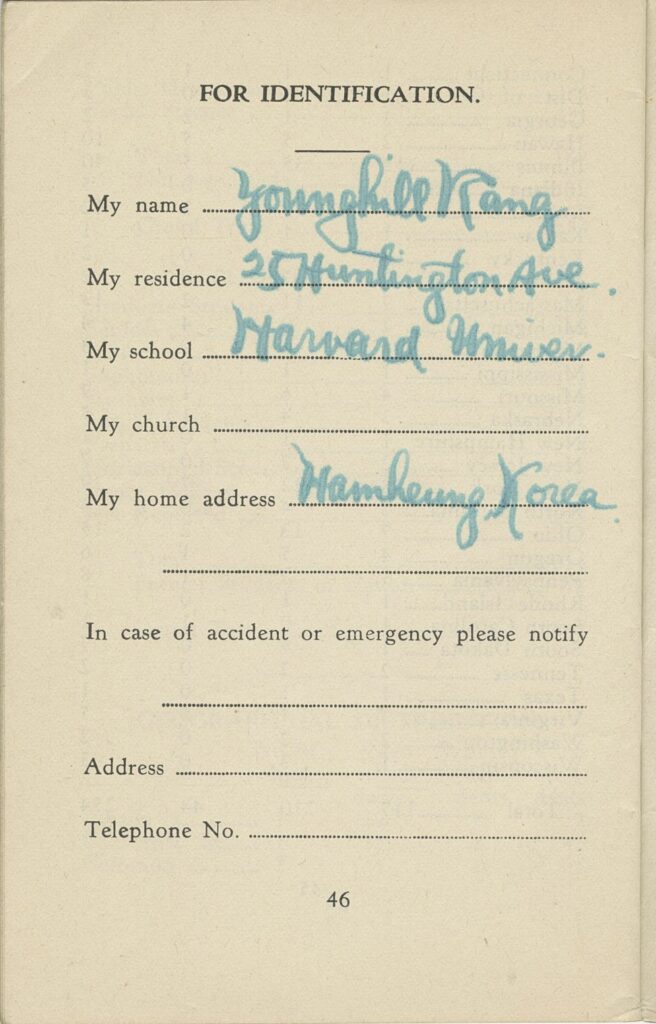

A forty-minute drive from New York City, the suburban town of Huntington retains a quaint charm today. Younghill Kang and Frances Keely lived here at 47 Creek Road for thirty-four years and raised their three children. The family lost the house; it’s since been demolished. In the massive parking lot behind the Panera Bread coffee shop stands a small blue-and-gold sign for poet Walt Whitman, another famous Huntington resident. And beyond the curve of Main Street lies the Huntington Historical Society. The Younghill Kang archive lives inside.

Motioning at two file boxes, archivist Karen Martin told me these papers and photographs were donated to the Society by a stranger who pulled them out of the trash heap on a sidewalk. The stranger thought they looked important.

Thanks to the efforts of such strangers as well as family members, archivists, editors, and journalists, among many others, Kang’s work has not disappeared. In love’s labors, immortality hasn’t eluded Younghill Kang yet.

Sources and thanks include: NYPL The Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room for Rare Books and Manuscripts; Karen Martin of Huntington Historical Society; Sara Ludovissy and Katie Lamontagne of Wellesley Archive; Walter K. Lew for Korean Culture and interview; Sunyoung Lee, Alexander Chee, et al. for Penguin Classics edition East Goes West (2019); Caitlin Hurst of Columbia UP; Ed Park for NYRB; Charlotte Brooks for blog Asian American History in NYC.

This essay is part of Sleeper Classics, a series in The Margins on under-appreciated works of Asian, Asian diasporic, and Asian American literature.