I embarked on this list with an assumption of scarcity. But I discovered an embarrassment of riches.

September 21, 2020

[Editor’s Note: This week, we relaunch our monthly Bookmarks feature with a five-part series on 100 essential books by Iranian writers available in English, researched and curated by Niloufar Talebi. Click here to jump to the gallery of nonfiction titles on the list.]

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Two impulses led me to compile this list: to resist the forces that stifle the publication and distribution of literature created by Iranians* and keep it off the world stage, and to celebrate the books that have reached readers of English.

The idea for this list originally came about as I raised these questions to myself:

What is this literature? What is (and is not) written and published inside Iran against pervasive state and self-censorship, cleverly reframed and filtered through tropes that elude the bureaucratic minefield and censors of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance? How and what can we, outside of Iran, with limited access, know of its diversity and aesthetic innovations? How do we overcome the barriers to international exchange? Are curators of the US book market willing to find ways to bring the creativity of literature in Iran to readers in translation?

Outside of Iran, what has been projected onto us by biased and often commodified productions, presentations, and consumption of our stories, that we in turn internalize—a different kind of censorship and self-censorship—and keep perpetuating in our literature? Are Iranians outside of Iran writing works against stereotypes enforced by the market that are not getting published? Can we write and publish beyond these stereotypes? Does this literature tend to repeat narratives whose fulcrum is always the 1979 Iranian revolution and historical events surrounding it that defined and disrupted our 20th century? Is there value in that repetition—how World War II and Holocaust narratives are reinforced—or does it limit our imagination and output? Where is the fine balance between turning our historical realities into literature and escaping the manner in which that literature is cast?

This list resists the following circumstances—ones that literature written inside and outside of Iran by authors of Iranian descent, in Persian, English, or any other language Iranian diasporic authors write in, faces to be available in English:

SUPPRESSION: The Shah’s regime before the 1979 Iranian revolution and the Islamic Republic after have both persecuted, silenced, and squashed writers and freedom of expression. Arbitrary arrest and detention of visitors and scholars from the West discourages unfettered cross-cultural dialogue that would support wider publication of Iranian literature.

LACK OF IRANIAN GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES: Though there is increasing support from individual and institutional patrons in the Iranian diaspora for Iranian/Persian studies programs in the United States, the government of Iran does not promote its literature within the United States’ publishing industry. That is, not beyond the limited attempts with lean resources of works that promote its ideology, or are deemed “neutral” (such as classical works), or present a revisionist packaging of Iranian literature and intellectual output, mostly executed in translations whose quality would not make them competitive for international distribution. There is no Iranian equivalent of the Alliance Française or similar institutions that help propagate European literature in other countries, for example. This lack of support to commission and publish original works or translations of books by Iranians means very few authors and translators can pursue the vocation professionally, or engage in sponsored cultural exchanges like those offered by the Fulbright Program. As for dedicated translation awards in the United States, I am aware of only one for translation from the Persian into English, the Roth Endowment’s Persian Translation Prize.

COPYRIGHT: Iran hasn’t signed the 1886 Berne Copyright Convention that protects literary and artistic works by providing creators with the means to control how their works are used, by whom, and on what terms. And because there’s no copyright treaty between Iran and the US (see, for example the United States copyright law, 17 U.S.C. § 104), works by Iranian authors first published in Iran fall immediately into the public domain in the United States. That leaves Iranian authors and publishers with no US rights to sell and little incentive to pursue US deals for already-published works. Iranian publishers freely translate and market books published in the rest of the world, leaving little incentive for formal and bilateral book deals. Furthermore, despite the law, for a translator, proving that a work published in Iran is in the US public domain is surprisingly difficult, which makes securing a publishing contract that much more complicated.

SANCTIONS: But even when US translators and publishers seek “moral” rights, like “authorization to publish” or “endorsement,” from Iranian authors and publishers, or when Iranian authors seek to publish their works in the US, there are very limited legal pathways for giving Iranian authors any compensation. Any service exported (directly or indirectly) to Iran is prohibited by US Treasury Department regulations, paid or not. The very fact of providing services such as translating or lecturing, for example, could pose a threat to even unpaid persons who may run the risk of prosecution. This risk is ironic because works by Iranian authors published in Iran are in the US public domain, so anyone could translate them without permission of the author, yet seeking permission could create a “service.” And, of course, permission is never required to lecture about a work. Not knowing the details of the sanction law, and not wanting to navigate complicated legalities, many choose to forego projects and collaborations. Financial sanctions and the Trump travel ban mean that no writer residing in Iran can independently or easily travel overseas to promote their work, nor can a translator easily and openly travel to research and work in Iran. Sanctions also mean that academic conferences get cancelled at a moment’s notice because attendees’ travel documents are not issued or revoked.

LIMITED INTEREST IN TRANSLATED WORKS: The US book market supports very few works in translation. Of that slim number, a tiny percentage has gone to literature by Iranians in translation—from the Persian and other languages its diaspora writes in. And in most cases, publishers’ and gatekeepers’ interest tends to peak during heightened political tensions and favor narratives of otherness, distress, and dissent against the Iranian regime. Even independent publishers dedicated to literature in translation have not published many (or in many cases, any) works by Iranian writers. More on this later during the release.

LIMITED NUMBER OF TRANSLATORS: Where Spanish and German literature, for example, have translators to spare, Iranian literature does not. With so few translators active and publishing opportunities so sparse, territorial tendencies narrow the supply still further and keep valuable works from the English-speaking public. My own experience of this while translating the Iranian poet, Ahmad Shamlou—included in Self-Portrait in Bloom—shows the costs this territoriality imposes.

APPROPRIATION AND COMMODIFICATION: An American reader will consume plenty of appropriations of classical Persian literature (reductions of the poetry of Rumi, or fabricated poems attributed to Hafez), productions that frame and reframe contemporary narratives that are written in earnest but are co-opted and sensationalized as dramas of suppression only to confirm the West’s demonized projection of the East and of itself as the savior of minds that it confers endorsements to (Nobel Peace Laureate, Shirin Ebadi’s Iran Awakening: One Woman’s Journey to Reclaim Her Life and Country, and as reflected in the choice of titles and marketing copy of most books, including some on this list), or projects whose native informant authors perform difference from and superiority to their own culture by aligning themselves with the values of the West, escaping the barbaric East to be saved in the West, thus further othering their own while serving the agendas of American Empire (Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran, and Marina Nemat’s Prisoner of Tehran). Western readers raised on this diet will only seek to understand the East through these lenses, and publishers will continue to produce what caters to that taste. At best, writers who wish to secure publishing contracts are subconsciously swayed to produce such narratives, or be comfortable with such framings of them.

This list also celebrates that despite challenges—which only show just how much further we can go to champion this literature—the abundance of literature by writers of Iranian descent, both at home in Iran and abroad, available in English is astonishing. Waves of migration out of Iran since 1979 have effectively resulted in the formation of a new literature. Since this list is a tip of the iceberg of the growing body of works by this subset, it is fair to assume that there is a significant body of literature here to warrant a major category and literary tradition of its own that contributes to the canon of world literature, however that canon is defined, its native environment the world itself.

I embarked on this list with an assumption of scarcity. But during the research process, I discovered an embarrassment of riches, and came to realize that what has always made this literature seem peripheralized to me is not in the quality or quantity of available works, but in their positioning—as a literature of other. Iranians at home and abroad have tended to look to cultural institutions and discourses of the West for validation of their writings and identity. And the West has largely failed us while enjoying its self-made and -maintained privilege. But the West’s marginalization comes with a gift: we must (re)center ourselves. I hope that this list helps to deliver us from our search for Western validation and urge us toward active self-regard, solidarity, and authority. Toward fiercely championing and lifting our own compatriots and work, on our own terms, to the world.

This list is by no means comprehensive. It includes books written inside and outside Iran by authors of Iranian descent, in Persian, English or any other language Iranian diasporic authors write in, and available in English. It omits theatrical, journalistic, sociological, and scholarly works. For the most part, these books have been published between 2000-2020. Many of the authors listed have written several books, but are listed by one title to allow this list to contain as many different writers as possible. The numbers on this list do not indicate rank. Each category is sorted by publication date.

________________________________________

*A note on the usage of “Iranian” versus “Persian:”

For purposes of this list, I’ll use “Iranian” for people born in the modern nation-state of Iran and their descendents outside of Iran. And I’ll use “Persian” for the language that many of them speak and write in. Not included on this list are authors from Tajikistan and Afghanistan, for example, where Persian is also spoken as a mother tongue, nor authors from Iran who write in all the other languages spoken in Iran. I’ve adopted this convention not from an exclusionary intent, and not because I am suggesting that there is something permanent or unchanging about the state of Iran or its borders or Iranian culture, but because more inclusive parameters would require a list much longer than this one. Even with these constraints, this list of 100 books mentions two and a half times as many.

That convention gets complicated when we’re dealing with writers active before the current nation-state of Iran existed. There were many political and cultural domains where Persian was the language of culture and literary production. And many writers in Persian lived in those states and are still read and still beloved in Iran. For example, Rumi was born in the greater Khorasan area of greater Iran, somewhere in present-day Tajikistan or Afghanistan, long before the current nation-state of Iran existed. Does that make Rumi Iranian? Not as I’m using the term. But his works are classics of Persian literature, widely read and studied inside and outside of Iran today.

For further Reading on this distinction, see Divided by a Common Tongue: Exclusionary Politics of Persian-Language Pedagogy by Aria Fani, Ajam Media Collective, October 5, 2015

I would like to thank my readers, Kaveh Bassiri, Aria Fani, Lida Nosrati, and E. Evans, whose input was instrumental in the writing of this introduction and list. And The Margins editor, Jyothi Natarajan, and her team, for taking this project on and ushering it through the many months it took.

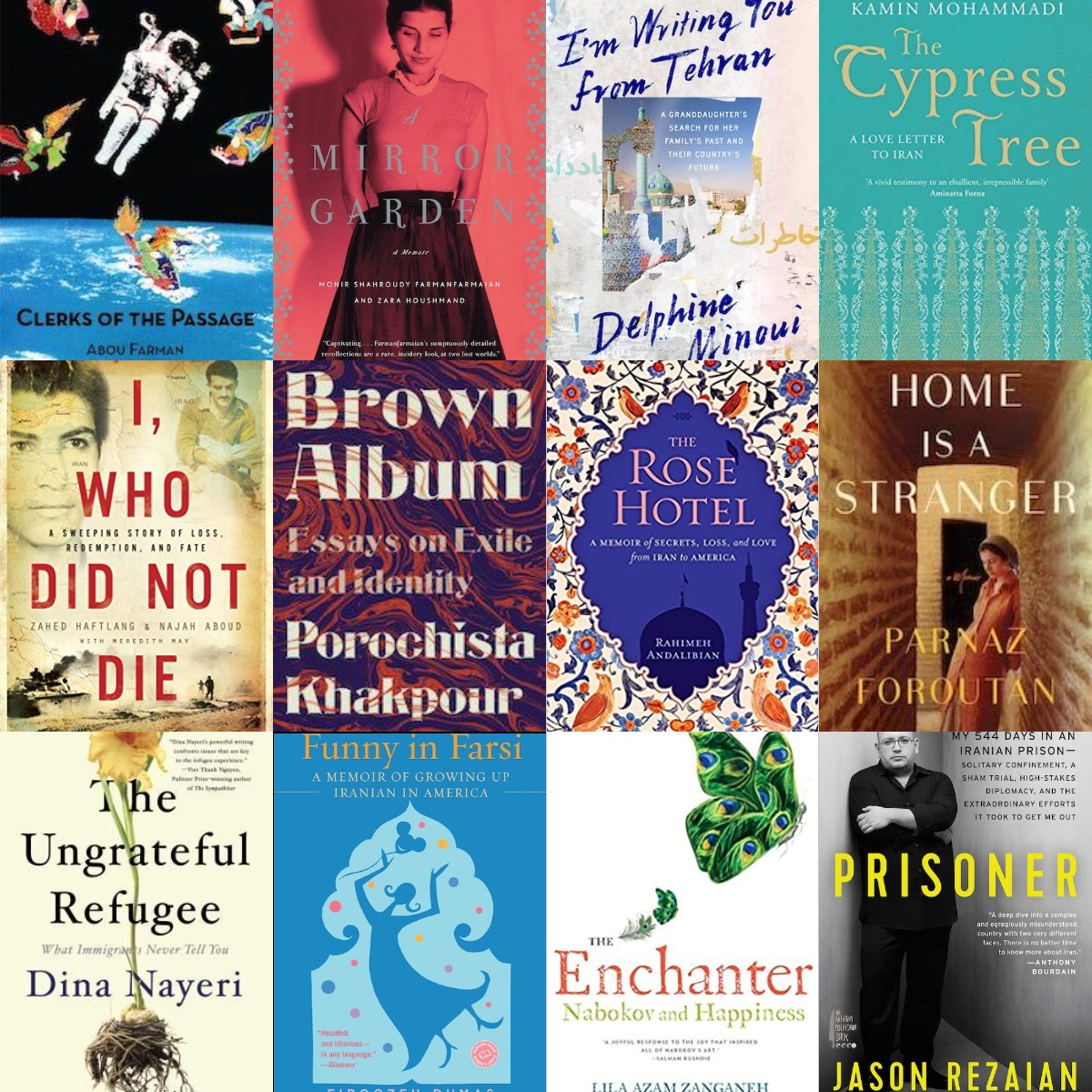

We begin our weeklong series of 100 Essential Books by Iranian writers with an imaginative array of twelve memoirs and essay collections.

1. Brown Album: Essays on Exile and Identity by Porochista Khakpour (Vintage 2020).

A collection of essays drawn from more than a decade of novelist Porochista Khakpour’s work and with new material included, Brown Album reveals the tolls of the immigrant life and the windy path to self-possession. These essays range between reflections on Tehrangeles and its most ostentatious salesman, Bijan, to travels to the American south, to life as a club girl in New York. Khakpour is also the author of a memoir, Sick, and two works of fiction, Sons and Other Flammable Objects and The Last Illusion.

2. Home is a Stranger by Parnaz Foroutan (Amberjack Publishing, 2020).

Foroutan returns to Iran nineteen years after her family fled, struggling to find a place for herself between the American girl she is and the woman she hopes to become in a world she only partially understands. Written with the same literary grace and passion as her novel, The Girl from the Garden, this memoir is about the meaning of desire, and the transcendence of boundaries.

3. I’m Writing You from Tehran: A Granddaughter’s Search for Her Family’s Past and Their Country’s Future by Delphine Minoui, Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan (Picador, 2020)

In 1998, then 22-year-old French Iranian journalist Delphine Minoui traveled to Iran for the first time since the revolution, and ended up staying for 10 years. Her memoir, written in the form of a letter to her grandfather who died in 1997, blends global history with stories of her family and narrative nonfiction from her early years as a reporter.

4. Prisoner: My 544 Days in an Iranian Prison by Jason Rezaian, (Anthony Bourdain/Ecco, 2020).

Half-Iranian and Northern-Californian Jason Rezaian made a life-changing decision to move to Iran to pursue journalism, reporting human interest stories and offering political analysis. He served as a guide for Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown. In July 2014, while working as a Washington Post Tehran bureau chief, he was arrested by Iranian police and accused of spying for America. Rezaian soon realized the impossibly high diplomatic stakes. Written with wit, humor, and a literary touch, Prisoner brings to life a fascinating story in all its complexity.

5. The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You by Dina Nayeri (Catapult, 2019).

Born in Iran during the revolution, Dina Nayeri writes of her refugee story, from living in an Italian hotel-turned-refugee camp with her mother and brother to gaining asylum in Oklahoma. Along the way, she pieces together the stories of other refugees and asylum seekers, reminding us of “the pain and horrors refugees face before and long after their settlement” (New York Times). Nayeri is also the author of two novels, Refuge, and A Teaspoon of Earth and Sea.

6. I, Who Did Not Die by Zahed Haftlang, Najah Aboud, Meredith May (Regan Arts, 2017).

In 1982, during the Iran-Iraq War, 13-year-old Iranian child soldier Zahed Haftlang was ordered to kill 29-year-old Iraqi soldier Najah Aboud, but decided instead to spare his life. Written with journalist Meredith May, the two men tell their story apart and together.

7. The Rose Hotel: A Memoir of Secrets, Loss, and Love From Iran to America by Rahimeh Andalibian (National Geographic, 2015).

Psychologist Andalibian’s memoir revisits her childhood growing up in a wealthy Iranian family. She uses her skills in clinical psychology to take the reader through her personal family trauma, which includes rape and murder, as well as the culture shock of displacement and assimilation that came with moving to the United States.

8. Clerks of the Passage by Abou Farman (Linda Leith Publishing, 2012).

This is a journey in the company of migrants, from the 3.5 million year-old bipedal hominids from Tanzania, to an Iranian refugee who spent seventeen years in the transit lounge at Charles de Gaulle airport, from Xerxes to Milton to Revelations, from Columbus to Don Quixote to Godot. Farman is also the author of On Not Dying: Secular Immortality in the Age of Technoscience (University Of Minnesota Press, 2020). Immortality has long been considered the domain of religion. But immortality projects have gained increasing legitimacy and power in the world of science and technology. Following a footnote on cryogenics that led him down a rabbit hole, Farman argues that secular immortalism is an important site to explore the tensions inherent in secularism: how to accept death but extend life; knowing the future is open but your future is finite; that life has meaning but the universe is meaningless.

10. The Cypress Tree: A Love Letter to Iran by Kamin Mohammadi (Bloomsbury UK, 2011).

This book is compelled by humanizing Iran and painting a true portrait of it in contrast to media portrayals, and by the author re-identifying with her Iranian-ness. Mohammadi’s family moved to the UK when she was 9 years old, after the revolution, where her childhood was filled with Christmas trees and royal watching. It wasn’t until her mid-twenties that she returned to Iran, where she found her roots. This moving and passionate memoir is a love letter both to Kamin’s extraordinary family and to Iran itself, an ancient country which has survived so much modern tumult but where joy and resilience will always triumph over despair. A travel writer and journalist, Mohammadi’s most recent book, Bella Figura: How to Live, Love, and Eat the Italian Way, chronicles her year in Italy.

10. The Enchanter: Nabokov and Happiness by Lila Azam Zanganeh (W. W. Norton & Co., 2011).

Nabokov’s creative reader Lila Azam Zanganeh lends life to this vision as she shares the joy to be found in reading the masterpieces of “the great writer of happiness.” Plunging into the luminous worlds of Speak, Memory; Ada, or Ardor; and Lolita, Azam Zanganeh seeks out the Nabokovian experience of time, memory, sexual passion, nature, loss, love in all its forms, and language in all its allusions, and shows us how literature can make us happy humans and better lovers. Azam Zanganeh is also the editor of My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes: Uncensored Iranian Voices, a collection that showcases the real scope and complexity of Iran through contributions by Azar Nafisi, Marjane Satrap, Reza Aslan, Shirin Neshat, Abbas Kiarostami, Azadeh Moaveni, and Roya Hakakian.

11. A Mirror Garden: A Memoir by Monir Farmanfarmaian and Zara Houshmand (Knopf, 2007).

A memoir of a fascinating woman who would capture the art world with her mirror creations. Revered by Iranians both in Iran and in the diaspora, her work has appeared in major museums and art fairs across the globe. Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s rich tales are drawn from a life split between Iran and the United States. Zara Houshmand is a theater artist, writer, literary translator, and co-author of several books on Buddhism. Her most recent work is Moon and Sun, a bilingual selection of Rumi’s Rubaiyat in her translation.

12. Funny in Farsi: A Memoir of Growing Up Iranian in America by Firoozeh Dumas (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2004).

A New York Times Bestseller, finalist for the PEN/USA Award in Creative Nonfiction, and an Audie Award winner in Biography/Memoir, Funny in Farsi is a hilarious jaunt through a series of misadventures by immigrants in the struggle for cultural understanding. Dumas is also the author of Laughing Without an Accent, and It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel.

Day Two: Poetry, Hybrid Works, Anthologies >

Day Three: Graphic Novels, Culinary Books, & Children’s/YA Literature >>

Day Four: Classics in Translation >>>

Day Five: Fiction >>>>

Introduction and List © 2020 Niloufar Talebi