Works of the classical period that appear in multiple translations

September 24, 2020

[Editor’s Note: This week, we relaunch our monthly Bookmarks feature with a five-part series on 100 essential books by Iranian writers available in English, researched and curated by author and translator Niloufar Talebi. Read the introductory essay to the series and the first list of books here. Below, find an introduction today’s installment and jump down to the list of classics in translation.]

◻︎◻︎◻︎

*The variations in spelling of names and titles arise from different systems of transliteration, one reflecting more closely the modern Persian parlance in Iran and the other closer to the romanization of Arabic.

Translated works are peppered throughout this list. To understand why more English translations of literature by Iranians are not available and do not appear on most literary and translation awards lists, I contacted several independent publishers of literature in translation that have not published works by Iranian authors to ask why.

The half that responded expressed that they were still looking for “the right fit.” One graciously attempted to qualify that elusive fit: “…writing we believe speaks to or against the best contemporary writing in English: we want our books to excite and challenge readers in the same ways the best new books in English do.”

The qualifier seems antithetical to the project of publishing translated literature, colonial to its very core. What does it say when literature from other cultures is ignored for its own native offerings, but rather weighed against literature in English, the Anglophone center? What happened to literature being our passport to the world?

Now on to the variables in the production of translations themselves, which result in a myriad of possibilities, the full discussion of which is beyond the scope of this introduction, but I will briefly mention a few factors:

The argument that translators without fluency in the original language do not produce or at least participate in producing valuable translations is invalid. This assumption is often conflated with another factor, that of producing loose renditions that veer too far from the original, which is an interpretive and formal choice, and not necessarily resulting from a lack of fluency in the original language and culture.

There there is a spectrum on which translators reference cultural elements. More flavor from the original culture moves the new reader closer to the author, while more flavor from the new reader’s culture moves the author to that reader. This used to be referred to as a dichotomy of foreignization versus domestication. Each approach has benefits and drawbacks, each engaging and constructing different versions and readers.

Given that these variables lead to infinite possibilities, the more and diverse translations that exist of a work, the more we can interact with it. Quality is key, but sometimes quantity has its advantages—not only do more translations increase the chances for high quality interpretation and translations, but also because collectively, they provide scaffolding for future readings, interpretations, and translations. Even unsuccessful translations have their function when they inspire the birth of new translators who aim to do better. There is great value and pleasure in comparative readings of translations. But such readings are only possible when multiple translations exist—a luxury the works of many Iranian authors do not have. Thankfully, some of the works of the classical period do appear in multiple translations. Here is a selection:

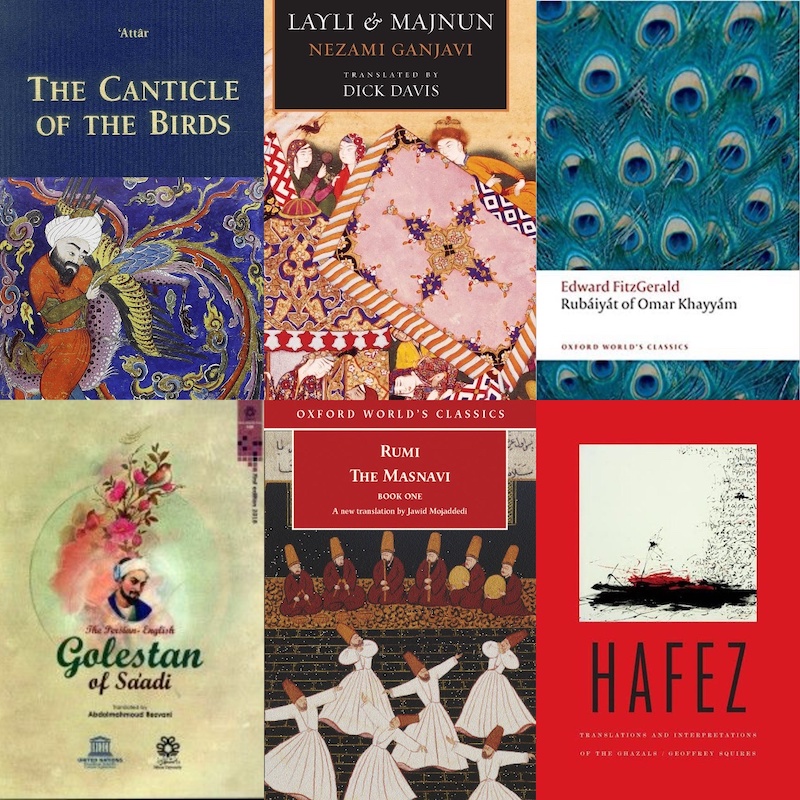

62. The poetry of Hafez Shirazi (1315-1390)

Hafez (also spelled Hafiz) is considered one of the greatest poets of the Persian language. The 14th century poet lived almost all his life in the southern city of Shiraz where he was involved in the court circles of various rulers and played an important role in the vibrant literary and spiritual life of the times. His poetry is collected in his Divan, which contains nearly 500 ghazals and some other verse. Hafez has been appropriated through various adaptations and productions not listed here. For further reading on this, see Omid Safi’s “Fake Hafez: How a Supreme Persian Poet of Love was Erased,” and Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee’s “Faking Hafez: Daniel Ladinsky and the Art of Translation.“

Translations include:

—Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (and Obayd-e Zakani and Jahan Malek Khatun), edited and translated by Dick Davis (Mage Publishers, 2019). This bilingual edition has the original Persian verses facing the English translations of its three contemporaneous Shirazi poets.

—Radical Love: Teachings from the Islamic Mystical Tradition, edited and translated from the Persian by Omid Safi (Yale University Press, Reprint edition, 2019). This is a collection of the love poetry and mystical teachings at the heart of the Islamic tradition in accurate and poetic original translations by leading scholar of Islam Omid Safi who brings together for the first time passages of the Koran sought by Muslim sages, mystical sayings of the Prophet, the poetry of several classical Persian poets including Hafez, Rumi, Sa’di, and Attar, and teachings of the path of “Divine love.”

—Hafez: Translations and Interpretations of the Ghazals, translated from the Persian by Irish poet Geoffrey Squires (Miami University Press, 2014). Squires, who lived in Iran for three years, captures the energy and depth of Hafez in contemporary English without archaisms or a predetermined interpretation, and gives powerful insight into the Persian culture. Based on 248 ghazals (just over half the Divan), this is one of the most comprehensive translations to appear and also one of the most varied, revealing aspects of the work—courtly, lyrical, satirical, mystical—that will surprise and delight many. Squires brings a poet’s ear to the task, capturing the energy, wit and beauty of the original which after all this time still speaks to us. He also breaks new ground in terms of translation strategy, using short interstitial prose pieces to punctuate and point the text. Detailed background notes are provided, and there is an extensive bibliography in Persian, English and French.

—The Poems of Hafez, translated from the Persian by Reza Ordoubadian (IBEX Publishers, 2005). Reza Ordoubadian’s translations make the poems of Hafez accessible to the English language reader, while remaining faithful to the nuances of Hafez’s language and thought in the original Persian.

—Wine and Prayer: Eighty Ghazals from the Divan of Hafiz (Library of Persia), translated by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. and Iraj Anvar (White Cloud/Caveat Press; 2nd Edition, 2019). This bilingual edition includes clean, modern translations, an afterword by Daryush Shayegan, a broad-ranging introduction, plus extensive and helpful notes to the translation. Hafiz was the unrivaled master of the ghazal, a lyric form roughly equivalent to the English sonnet in length, intensity, and complexity. In this volume, Gray has joined with Iraj Anvar, a scholar of Sufism and Persian poetry to present translations that capture the subtleties, paradoxes, and spiritual depths of the poet hailed by Persians as “the Tongue of the Invisible” and the “Interpreter of Mysteries.” Forthcoming from Gray is a new selection of Forugh Farrokhzad poems in her translation (New Directions, 2022).

—The Illuminated Hafiz: Love Poems for the Journey to Light, edited by Nancy Owen Barton (Sounds True, 2019). Vivid translations by Omid Safi, Coleman Barks, Robert Bly, Meher Baba, and others combine with Michael and Saliha Green’s stunning illustrations to bring the immortal poetry of the great Persian master to life.

63. The poetry of Sa’di Shirazi (1210-1291)

The 13th century Persian poet and prose writer, Sa’di (also spelled Saadi), a contemporary of Rumi, is one of the luminaries of the Persian literary canon. His works include the Bustan and Golestan (also spelled Gulistan), four books of ghazals, qasidas in both Persian and Arabic, quatrains, and short pieces. Sa’di is well known for his aphorisms, the most famous of which, Bani Adam, part of the Golestan, is displayed at the United Nations building in Edward Eastwick’s translation:

“All human beings are members of one frame,

Since all, at first, from the same essence came.

When time afflicts a limb with pain

The other limbs at rest cannot remain.

If thou feel not for other’s misery

A human being is no name for thee.”

Translations include:

—The Golestan, translated by Abdolmahmud Rezvani (UNESCO and Shiraz University, 2018) Though this title seems not to be available for sale outside of Iran, the creation of this high quality translation in Iran by an acclaimed Iranian professor of translation studies is noteworthy.

—The Gulistan (Rose Garden) of Sa’di: Bilingual English and Persian Edition with Vocabulary, translated by Thackston M. Wheeler (IBEX Publishers, 2017). The Gulistan, imbued with practical life wisdom, is a collection of moral stories divided into eight themes: The Conduct of Kings, The Character of Dervishes, The Superiority of Contentment, The Benefits of Silence, Love and Youth, Feebleness and Old Age, The Effects of Education, and The Art of Conversation. In this first complete English translation of the work in more than a century, Professor Thackston has faithfully translated Sa’di into clear, contemporary English.

—Selections from Saadi’s Gulistan (FARSI HERITAGE SERIES), translated with an introduction by Richard Jeffrey Newman (Global Scholarly Publications; First Edition, 2004). Newman has also translated a selection from the Bustan (Global Scholarly Publications, 2006). Both of the translations are accessible and of high literary quality. These translations were commissioned by an organization with ties to the Iranian government, the now-defunct International Society for Iranian Culture, and the selections to be translated were pre-selected by a committee in Iran. Both books are currently out of print, but available for download on Academia.edu.

There are more scholarly studies and translations of Sa’di’s Golestan and Bustan available, but no complete and contemporary literary translations of them, a vacuum to hopefully be filled.

64. The poetry of Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rumi (1207-1273)

Rumi was born to Persian-speaking parents in the greater Khorasan area of greater Iran at a time when it was a major center of Persian culture and Sufism. The exact place is unknown, but it would be in present-day Afghanistan or Tajikistan. When the Mongols invaded Central Asia sometime between 1215 and 1220, his family migrated westward and settled in Konya (in present-day Turkey), where Rumi eventually began a public life as an Islamic jurist and teacher, as his father and grandfather had been. Rumi’s shrine in Konya, where he died and is buried, has become a place of pilgrimage. A 1244 meeting with the wandering mystic, Shams-e Tabrizi, became a turning point in Rumi’s life. Shams challenged Rumi to question his scriptural education, debated the Koran with him, steered him to the idea of spirituality as oneness with God. Thus was Rumi transformed from an accomplished teacher and jurist into an ascetic. Four years later, when Shams disappeared one night, Rumi’s love for, and his bereavement at, the death of Shams found expression in an outpouring of lyric poems, which became Rumi’s Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi. Rumi’s other major works include the Masnavi-ye Ma’navi, a six-volume spiritual epic that holds a distinguished place within the rich tradition of Persian Sufi literature, and Fihi Ma Fihi, a prose book of 72 short discourses.

Rumi has been described as the “most popular” and “best selling” poet in the United States. Lifestyle gurus, Hollywood A-listers, and pop stars have appropriated popular offerings attributed to Rumi to spawn and celebrate their enlightenment. This popularity was perhaps sparked by new-agey renditions of Rumi by Coleman Barks after Robert Bly introduced him to Cambridge professor, A.J. Arberry’s literal and footnoted translations of Rumi, charging Barks with the task of “freeing them from their academic cages.” Barks would base his loose versions on A. J. Arberry’s and R. A. Nicholson’s earlier translations, and his collaboration with John A. Moyne. Often, critics of Barks’ renditions point to the fact that he is not fluent in Persian and works from previous translations. In my opinion, this approach to assessing a translation is problematic. Fluency versus access to the original text and its culture are two different matters. That Barks skips lines from the original and remixes poems to generate his aphorism-like morsels have less to do with his fluency or access to the original source, and more with his formal and interpretive choice. The criticisms likely stem from the erasure of the Islamic provenance of the original texts from the renditions.

One of the most common requests I get is to recommend my favorite translation of Rumi. I say: there are so many—indulge in comparative readings, particularly those by translators who provide the source from which the translation is drawn. Without this information, it’s close to impossible to compare translations or even be confident that the original was Rumi’s.

Translations include:

—The Masnavi of Rumi, Book One: A New English Translation with Explanatory Notes, translated by Alan Williams (I. B. Tauris & Company, 2020). In Book 1 of the Masnavi, the first of six volumes, Rumi opens the spiritual path towards higher spiritual understanding. Alan Williams’s new translation is rendered in easily readable blank verse and includes the original Persian text of the Masnavi edited by Mohammad Este’lami for reference, as well as an introduction, analysis, commentary, explanatory, and supplementary text by Williams. True to the spirit of Rumi’s poem, this new translation establishes the Masnavi as one of the world’s great literary achievements for a global readership.

—The Masnavi, translated by Jawid Mojaddedi (Oxford World’s Classics) (Oxford University Press, Book 1, 2008; Book 2, 2008; Book 3, 2014; Book 4, 2017). The Masnavi is widely considered to be the greatest Sufi poem ever written, and nicknamed “the Persian Koran.” Rumi composed his work to convey his message of divine love and unity, threading together entertaining stories. Drawing from folk tales as well as sacred history, Rumi’s poem is often funny as well as spiritually profound. Mojaddedi’s sparkling new verse translation is consistent with the aims of the original work in presenting Rumi’s most mature mystical teachings in simple and attractive rhyming couplets.

—Swallowing the Sun, translated from the Persian by Franklin D. Lewis (Oneworld Publications, 2013) This volume draws from the breadth of Rumi’s work, spanning his prolific career from start to finish. From the uplifting to the mellow, these polished translations will prove inspirational to both keen followers of Rumi’s work and readers discovering the great poet for the first time. Dr. Lewis is the editor (with Farzin Yazdanfar) of In a Voice of Their Own: A Collection of Stories by Iranian Women Written Since the Revolution of 1979 (Bibliotheca Iranica: Persian Fiction in Translation Series) (Mazda Pub; First Edition, 1996).

—Rumi’s Little Book of Life: The Garden of the Soul, the Heart, and the Spirit, translated by Maryam Mafi and Azima Melita Kolin (Hampton Roads Publishing Company, 2012). This is a collection of 196 poems by Rumi previously unavailable in English, translated by native Persian speakers. The translated works are referenced back to their original sources, and are accompanied by an index of first lines, how the original Persian poetry is indexed. Maryam Mafi has produced more Rumi books.

—Say Nothing: Poems of Jalal al-Din Rumi in Persian and English, translated by Iraj Anvar and Anne Twitty (Morning Light Press, 2008). Say Nothing captures the rich and varied tones of a mature voice that retains its youthful capacity for exaltation and revelation. This fully annotated, bilingual edition contains both short quatrains and longer ghazals, alternating forms that reflect the shifts in Rumi’s moods and inspirations.

—A Bird In The Garden Of Angels: On the Life and Times and an Anthology of Rumi, translated from the Persian by John A. Moyne and Richard Jeffrey Newman (Mazda Pub, 2007). This book is a Rumi reader for the general public. It contains a brief chapter on the history and doctrine of Sufism and mysticism, and a second chapter on the life and times of Rumi and his close associates. The rest of the book is divided into sections, each section containing an introduction and selections chosen and translated from the prolific writings of Jalaluddin Rumi and from a few other sources dealing with Rumi and his circle. Much of Rumi’s poetry and some of his prose have already been translated at various times and in various styles into many languages, including English. During the past two decades, there has been a surge of popular interest in Sufism and Sufi literature, and new translations in different poetic styles have been appearing. A few of the pieces in this volume were previously translated by Moyne and published jointly with Coleman Barks, but they are presented here in revised versions. Some of the prose and poetry in this book, however, has not been previously translated into English.

—Signs of the Unseen: The Discourses of Jalaluddin Rumi (Revised), translated from the Persian by Wheeler M. Thackston (Shambhala, 1999). A collection of Fihi Ma Fihi, Rumi’s lectures, discourses, conversations, and comments on various topics. Even in conversation Rumi expresses his spiritual insights in a style rich in allusion and figurative language. His themes include God’s beauty and beneficence, the continuum between form and substance, the here and the hereafter, and the centrality of love in the soul’s development.

—Rumi: Unseen Poems, translated and edited by Brad Gooch and Maryam Mortaz (Everyman’s Library, 2019). In this new translation—composed almost entirely of untranslated gems from Rumi’s vast oeuvre—Gooch and Mortaz aim to achieve greater fidelity to the originals while still allowing Rumi’s lyric exuberance to shine.

—The Rumi Collection, edited by Kabir Helminski (Shambhala, 2005). This is a selection from various works of Rumi. Translators include Camille Helminski, Kabir Helminski, Robert Bly, and John A. Moyne and Coleman Barks. To display the major themes of Rumi’s work, each of the eighteen chapters in this anthology are arranged topically, such as “The Inner Work,” “Praise,” and “Purity.” Also contained here is an index of titles and first lines, a biography of Rumi by Andrew Harvey, as well as an introductory essay by Kabir Helminski on the art of translating Rumi’s work into English.

For further reading:

—Rumi’s Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love by Brad Gooch (Harper, 2017), Rumi’s Secret reveals the unfolding of Rumi’s devotion to a “religion of love,” remarkable in his own time and made even more relevant for the twenty-first century by this compelling account.

—Rumi – Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi by Franklin Lewis (Oneworld Publications, 2014). Said to be a definitive study of Rumi in English, this book draws on a vast array of sources, from writings of the poet himself to the latest scholarly literature, this new anniversary edition of the award-winning work examines the background, the legacy, and the continuing significance of Rumi. With new translations of over fifty of Rumi’s poems and including never before seen prose, this landmark study celebrates the astounding appeal of Rumi, still as strong as ever, 800 years after his birth.

65. The Poetry of Fariduddin Attar (1145-1221)

Attar was a Persian-language poet, theoretician of Sufism, and hagiographer. Attar’s work has had enduring influence on Persian poetry and Sufism. His notable work in the English language is his Manteq-ot-Teyr (also spelled Mantiq-ut-Tayr), generally called The Conference of the Birds in English translation. Among other notable works are the Divan of ghazals, and the Tadhkirat Al-Auliya (Biographies of the Saints), a hagiographic collection of teaching stories about Muslim saints and mystics, culminating in accounts of the execution of the Sufi, Mansur al-Hallaj, who had uttered the words “Ana’l-Haqq,” meaning “I am the Truth” in a state of ecstatic contemplation, as well as the Elahi-Nameh (also spelled Ilāhī-Nāma) (The Book of Divine), a story in verse about a king who is confronted with the materialistic and worldly demands of his six sons. The Conference of the Birds is written in a masnavi form of rhyming couplets. In the allegorical tale about the soul’s search for meaning, the birds of the world gather to choose their sovereign. The wisest of them, the hoopoe (a bird often associated with King Solomon of the Bible), suggests they seek the legendary and mythical bird, Simorgh, who lives in the mountain at the edge of the world, then leads the birds—each of whom represent a different flaw that prevents humankind from attaining enlightenment—through seven valleys in order to reach the Simorgh. They learn the journey is not simple, and on the way, many of the birds drop out or die, only thirty of them arriving at the realm of the Simorgh. The word “Simorgh” in the Persian means thirty (si) birds (morgh). The lesson they learn is that they themselves are the Simorgh.

Translations include:

—The Conference of the Birds, translated from the Persian by Sholeh Wolpé (W. W. Norton & Co., 2018). Wolpé recreates the original Persian in a combination of English verse and poetic prose, and has adapted the poem as a stage play.

—The Canticle of the Birds (Éditions Diane de Selliers, 2014), based on the complete and further revised translation by Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (see below) and published by Éditions Diane de Selliers, it includes over 200 miniatures from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Persio-Afghan manuscript from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries as well as additional illustrations from Persian, Turkish, Central Asia, and Indo-Pakistani sources. The result is a tapestry of illuminated manuscripts with commentaries by Michael Barry and contributions by Leili Anvar that contextualize the art and the text in the history of eastern culture.

—The Conference of the Birds by Peter Sis (Penguin Books, 2013). This version for adults by illustrator and children’s book author Peter Sis, who consulted the Avery edition, is inspired by the Darbandi and Davis translation, but is ultimately stripped of its Islamic context.

—The Conference of the Birds by Alexis York Lumbard, illustrated by Demi, with a forward by Seyyed Hossein Nasr (Wisdom Tales, 2012). This version is adapted for children 4-8 years in both prose and verse.

—The Conference of the Birds, translated from the Persian by Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (Penguin Books, 2011). This book was originally published by Penguin Classics in 1984 and was revised in 2011 when a Prologue and Epilogue were added. Though the listing cites 1984 as the publication date, Dr. Davis confirmed that this is the 2011 revised edition.

Dick Davis has translated other classical works of Persian literature including Fakhraddin Gorgani’s Vis & Ramin. Davis is also the editor and translator of bilingual The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women, as well as the translator of discrete episodes from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (published by Mage Publishers, a US-based press dedicated to Persian literature and culture), and of the Shahnameh itself, a work that appears elsewhere on this list, but worth listing more translations of:

—Shahnameh: Persian Book of Kings, translated from the Persian by Dick Davis (Penguin Classics; Deluxe Edition, 2007). This prose and poetry version of almost the entirety of the work (excluding the exordium, the introductory portion of the oration), is so far the most complete English-language edition.

—The Teller of Tales: Stories from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, translated from English by Richard Jeffrey Newman (Junction Press, 2011). This book, which contains the only contemporary translation of parts of Ferdowsi’s exordium, covers the stories of the first five kings in the Shahnameh. The translations are based on the Warner brothers’ verse translation, as well as Ruben Levy’s prose version, The Teller of Tales realizes Edward G. Brown’s ambition to translate the Shahnameh into an alliterative verse form.

—In the Dragon’s Claws: The Story of Rostam and Esfandiyar from the Persian Book of Kings, translated from the Persian by Jerome W. Clinton (Mage Publishers; First Edition, 1999). The story of Rostam and Esfandyar is one of the most tragic episodes of the Shahnameh. It expresses a profound ambivalence about the demands of heroism, and is sharply critical of a monarch who exploits the courage and loyalty of his heroes to further his own selfish ends.

Back to Attar translations:

—The Speech of the Birds, translated from the Persian by Peter Avery (Islamic Texts Society, 1998). This is a complete and annotated translation in verse.

—Bird Parliament, rendered by Edward FitzGerald (free PDF linked here). According to the Encyclopedia Iranica, FitzGerald worked on the Bird Parliament, the third of his Persian translations, intermittently between 1856 and 1862. He probably realized it was his least successful translation, demonstrated by the fact that he did not attempt to publish it. He cut the poem so extensively (from roughly 4500 to 1500 lines) that the poem’s structure, on which he commented disparagingly, as he clearly did not understand its details, all but disappeared. He also made some glaring changes to the text. There are some fine passages of English poetry in the translation, notably towards the end when the birds meet the Simorgh, and in the beautifully rendered brief anecdote of the child sent out on a windy night with a lamp.

—Muslim Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat Al-Auliya‘ translated by A.J. Arberry (Penguin Books, 1990). This is an abridged English translation.

*In addition to my own research, I consulted Kaveh Bassiri’s 2014 essay, “The Gathering of the Conference of the Birds” as it appears in the Michigan Quarterly Review.

66. The poetry of Nezami Ganjavi (1141-1209)

Nezami (also spelled Nizami), considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature, brought a colloquial and realistic style to the Persian epic. Nezami is best known for a set of five long narrative poems known as the Khamsa (Quintet) or Panj Ganj (Five Treasures): Makhzan-ol-Asrâr (The Treasury of Mysteries), Khosrow o Shirin (Khosrow and Shirin), Leyli o Majnun (Layli and Majnun), Eskandar-Nâmeh (The Book of Alexander), and Haft Peykar (The Seven Beauties).

Translations include:

—Layli and Majnun, translated from the Persian by Dick Davis (Mage Publishers, 2020). Leyli and Majnun is a tragic love story about the 7th-century poet Qays ibn al-Mullawah and his ladylove Layla bint Mahdi. In the same way that Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet has become the archetypal Western love story, Nezami’s Layli and Majnun occupies an uncontested place as the iconic love story of the Middle East. Nezami collected material from various sources about Majnun and portrayed a vivid picture of the famous lovers. This story is passed to Persian, Turkish, and Indic languages from fragments in Arabic, most famously through the narrative poem composed in 1188 by Nezami as the third part of his Khamseh. Dick Davis brings Nezami’s classic to life for the first time in brilliant and moving English verse that captures all the extraordinary power and ingenuity of the original poem. Meanwhile, an introduction and copious explanatory notes shed a fascinating light on Nezami’s life and work, and the astonishing virtuosity of his poetic style, that help set the stage for the reader’s enjoyment of this tour de force of Persian literature. Many imitations have been contrived of Nezami’s work, several of which are original literary works in their own right, including Majnun o Leyli by Amir Khusrow Dehlavi (1299), and Jami (1484), Hatefi (d. 1520), and Fuzûlî (d. 1556), whose Azerbaijani language version of the story was adapted by the Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov as what became the Middle East’s first opera, premiering in 1908.

—Haft Peykar, A Medieval Persian Romance, translated from the Persian by Julie Scott Meisami (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.; UK ed. Edition, 2015). This volume contains an introduction, explanatory notes, a glossary, and a chronology of Nezami’s life. Completed in 1197, the Haft Peykar is an allegorical romance of great beauty and depth, its central theme of self-knowledge as the path to human perfection conveyed in rich and vivid imagery and complex symbolism. It tells the story of the Sassanian ruler Bahram V Gur and of his spiritual progress. He is guided towards wisdom and moral enlightenment by the seven tales of love told to him by his brides, the Princesses of the Seven Climes. Each tale depicts a love-quest which ends sometimes in failure, more often in fulfilment, as desire is guided by virtue. Haft Paykar means ‘Seven Images/Portraits/Beauties’, and it refers to the seven princesses, their seven tales, and the seven planets.

—Mirror of the Invisible World: Tales from the Khamseh of Nizami Ganjavi (English and Persian Edition) translated by Peter J. Chelkowski, (Metropolitan Museum of Art; First Edition first Printing edition, 1975). This book contains the stories of Khosrow and Shirin, Layla and Majnun, and the Seven Princesses (or Beauties) told in prose and accompanied by the classical illustrations of their scenes. The publication of this book coincided with the opening of the newly installed Islamic Galleries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This volume appears to be out of print, but a free PDF of its English-only edition is available through the link provided above.

67. The poetry of Omar Khayyam (1048-1131)

Omar Khayyam was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, philosopher, and poet born in Neyshabur, in northeastern Iran. The poetic output attributed to Khayyam was in the form of quatrains (ruba’i) that celebrated song and wine and lovers and doubted the afterlife. What became widely known to the English-reading world as the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is a loose rendering by Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883), first published in 1859. According to Louis Untermeyer’s preface in the 1946 Random House edition, FitzGerald was snubbed and decided to self-publish his rendering anonymously, which went unnoticed and unreviewed. Over his lifetime and through several editions of the work, he arrived at one hundred and one quatrains he considered the final version. FitzGerald’s effort was a combination of aspects of Khayyam’s original verses with his own poetic and editorial input. It was the Pre-Raphaelite poet and painter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who browsing bargains in penny boxes of old treasures discovered a copy and quoted from it wherever he went. Soon, there was a buzz about the poem. Some thought the mysteriously unsigned work was not a translation but a disguise, others argued that it was an extraordinary hoax.

Translations include:

—The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam: A New Translation from the Persian by Juan Cole (I.B. Tauris, April 2020), a modern translation, complete with critical introduction and epilogue.

—The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: First and Fifth Editions by Edward FitzGerald (Dover Publications, 2011) This edition has FitzGerald’s first and fifth editions, so readers can see the progression of his renditions.

—The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam: The Astronomer-Poet of Persia by Edward FitzGerald, edited by Daniel Karlin (Oxford University Press, USA , 2010). Daniel Karlin’s richly annotated edition focuses on the poem as a work of Victorian literary art, considering that the late-Victorian and Edwardian popularity of the poem rested on a shallow reading based on its shimmering surface, thereby doing justice to the scope and complexity of FitzGerald’s rendering of Omar Khayyam, who as FitzGerald put it, sang of what all men feel in their hearts but was not expressed in verse before. Karlin provides a critical introduction which documents the poem’s treatment of its Persian sources, along with its multiple affiliations with English and Classical literature and to the Bible. A selection of contemporary reviews offers an insight into the poem’s early reception, including the first attack on its status as a translation.

—The Ruba’iyat of Omar Khayyam, translated from the Persian by Peter Avery and John Heath-Stubbs (Penguin Books, revised 1981). This selection is accompanied by illustrations, and its translations of 235 ruba’i are based on selections made by Sadegh Hedayat, and Muhammad’ Ali Furughi and Qasim Ghani.

—The Wine of Nishapur: A Photographer’s Promenade in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by photographer Shahrokh Golestan, translator Karim Emami, and calligrapher Nasrollah Afjei (Mazda Pub; Reprint Edition, 1997). This photographic journey into Khayyam’s world of the rubaiyat is accompanied by new English translations by noted critic, editor, and leading Iranian translator, Karim Emami, and the original poems penned in calligraphy. In compositions of exquisite beauty, the plates are the fruit of extensive research into form and color.

< Day Three: Graphic Novels, Culinary Books, & Children’s/YA Literature

<< Day Two: Poetry, Hybrid Works, Anthologies

<<< Day One: Introduction + Nonfiction