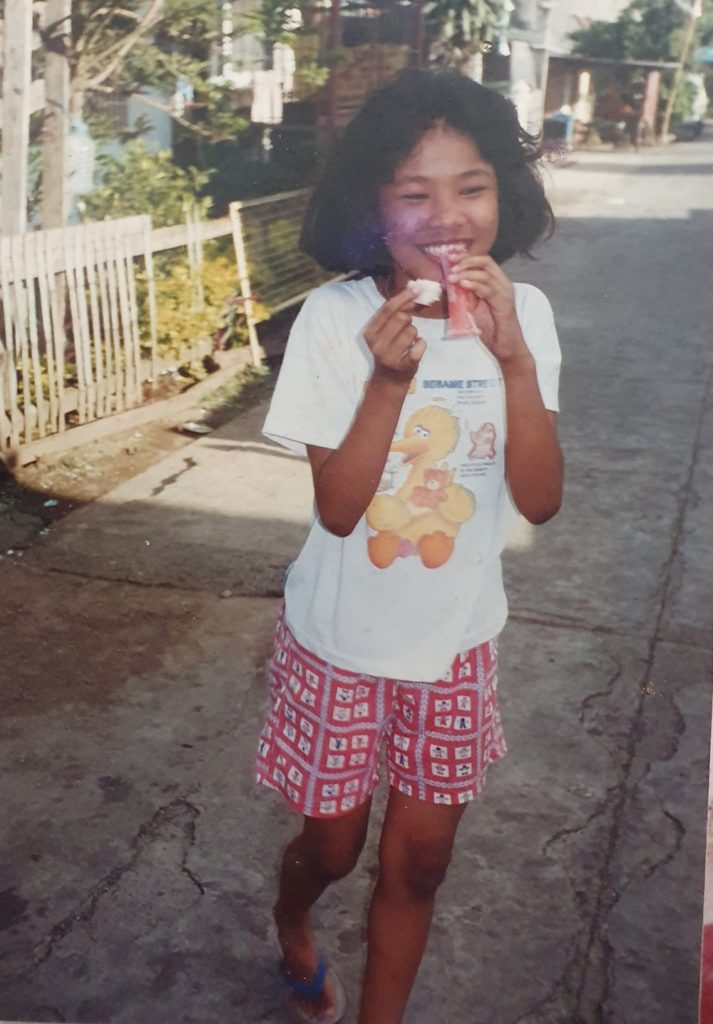

The morning I was hit by a bicycle was the last time Ma asked me to do an errand before she left us to work in another country.

Editor’s Note: The following essay by Romalyn Ante is part of a notebook of writing on the theme Nurse. Read other pieces in the collection gathered here.

Exhibit One

There is a keloid scar at the centre of my hairline, as big as my thumb, thin as a willow leaf. The remnant of a wound from when I was eleven and was hit by a bicycle as I walked to the panciteria eatery at the end of our street to ask the owner, Ka Marta, if she had some red chillies to spare.

A few days before my mother left our country to work as a nurse overseas, she was preparing a meal for the family. Chicken feet adobo. Ma said, “It’s more delicious when it’s spicy,” as she scrambled through a woven bowl for chillies, but found only a couple of tiny dry and desiccated ones.

The heat warped the road of our village and stitched the shadows of pandan trees and santan shrubs on the sidewalk. Perhaps it was the glare of the midday sun, but I did not see the cyclist coming. Just the blur of his shirt and his helmet as he sped past, knocking me over. The bright Batangas air flared with the rust-scent of blood.

I ran back inside our house not with a handful of chillies, but with my palm cupped over my forehead, blood streaming between my fingers.

I was awake when the doctor stitched my wound. I could not feel anything apart from the cold blood that ran down my temples, the occasional tugging of thread from my forehead. I looked at Ma’s face peering over the doctor’s shoulder. Ma’s gaze was steadfast, and somehow I felt a sense of comfort knowing she was there. Ma nursed my wound—she cleaned it with Betadine and dressed it regularly, and also cut and tweezed out the stitches when we couldn’t afford to go back to the doctor.

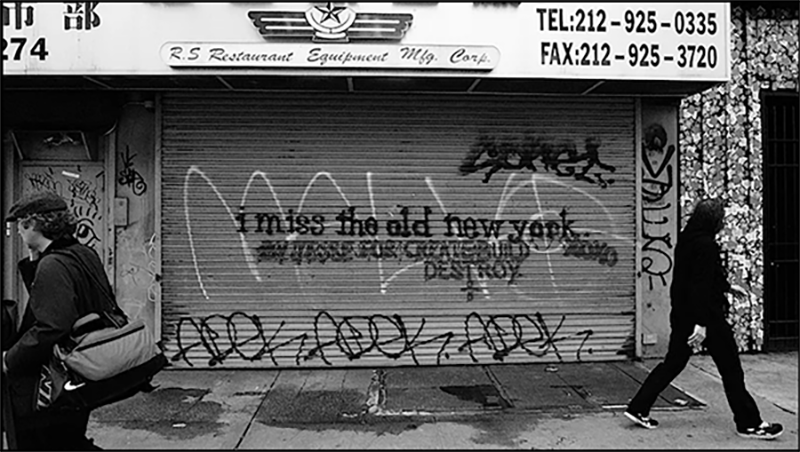

The word scar originates from late Latin eschara, eskhara in Greek. It means a “scab formed after a burn,” and literally translates as “hearth” or “fireplace”. When I look at my face now all I can see is an imperfect portrait: the keloid scar, a thick dab of copper-red acrylic, a burnt island seen from a bird’s-eye view. It breaks the middle of my hairline and no hair can grow from it.

I hated my scar. Whenever my school classmates pushed their hair back with pink polka-dot headbands or pinned their fringes away from their faces with glittering Jolina-butterfly clips, I would always part mine sideways to cover the mark. But from time to time a strong gust carrying waves of discarded leaves and grey rain would reveal the bald patch. No one can really hide a scar.

Exhibit Two

Scarification or intentional scarring has been practiced by many cultures around the world. When the Spanish colonizers landed on the shores of Visayas and saw the natives of our land, they named them Pintados, “the painted ones.” Ancient tribesmen pricked their skin with sharp wood and rubbed black powder in the wound to tattoo intricate symbols such as sea wave, fire, and curlicues of clouds. These patterns signified bravery and beauty. Each coil of black waves narrated the warrior’s journey, their trials and triumphs. The more tattoos a person bore and the more scarred their skin was, the more valued and revered they were.

The Maori and Pacific Islanders share a similar tradition of scarification to symbolize honor and prestige, while in the old Sepik region of Papua New Guinea (where it is believed that crocodiles created humans), young men were initiated into manhood by having their skin cut with bamboo slivers. The wounds solidify into scars that look like the bumps of crocodile skin, symbolizing their rebirth into “crocodile men.”

If wounds and scars symbolize growth and honor, then shouldn’t we all be proud of them?, I ask myself nowadays, two decades after I got my forehead scar, as I button my blouse in front of a mirror, ready for my day’s work as a nurse in my second home, England.

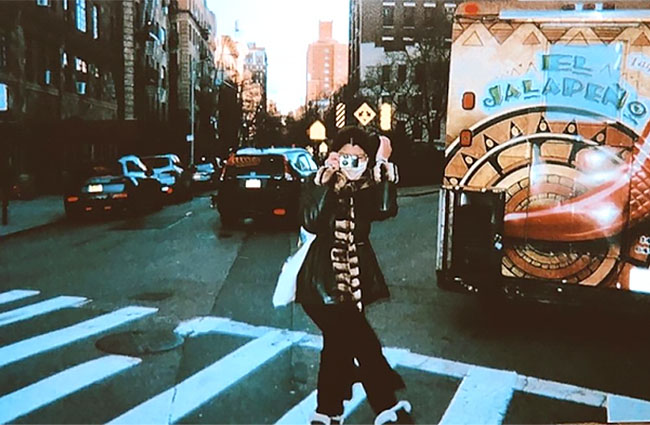

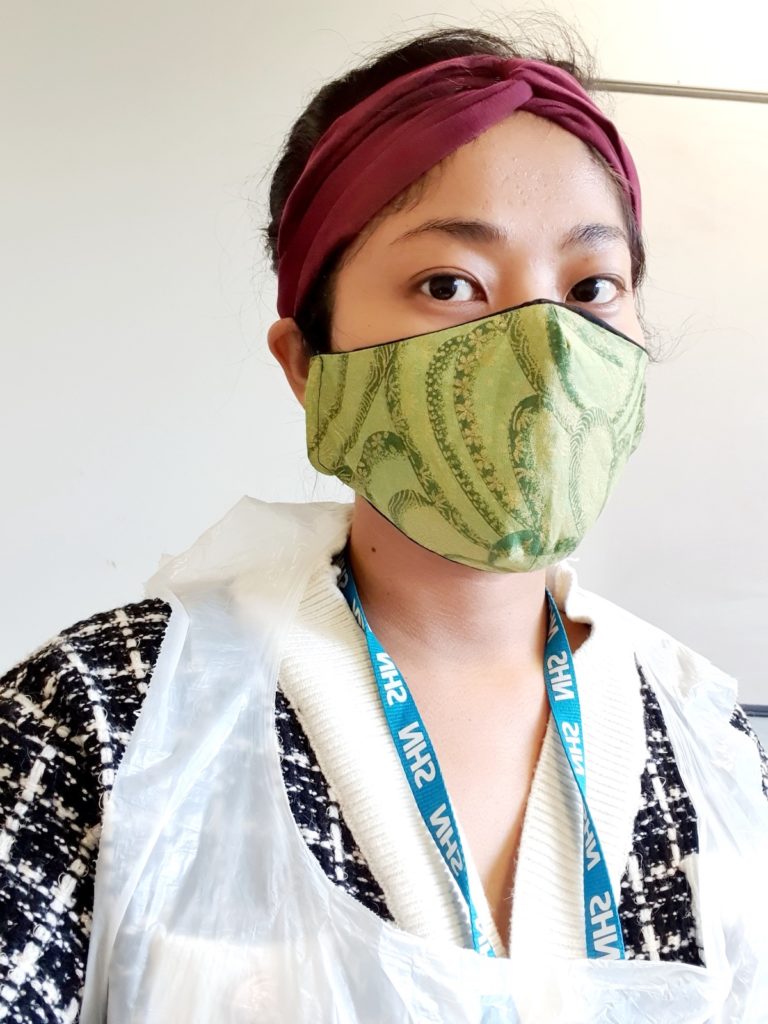

Ma is currently away, working as a frontline nurse somewhere in Wales where her agency has sent her. We sometimes send pictures of ourselves to each other in our PPEs, letting each other know how we are both doing at work. Once, Ma sent a picture of her with her nose bridge bruise-red, runneled like a battlefield’s trench in a dried landscape. Her cheeks sore-pink. When I zoomed in, I could also see her brows bombarded with beads of sweat; the edges of her hair-cap a darker shade of blue from the moisture.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the media has portrayed healthcare workers as “heroes.” This morning, I woke to the vibration of my mobile, my face illuminated by the LED light. On Facebook, Ligaya, a Filipino nurse who lives in the same neighborhood as me, had shared an endless scroll of articles about the first 11 doctors who died of COVID-19. All from Black and ethnic minority groups.

Soon, there is more news about deaths from the community of ethnic minority healthcare workers. Bughaw, a nurse who was recruited by the UK’s National Health Service from the Middle East only two months before the first lockdown, phoned my friend Masigasig who is a nurse himself to ask, “Paano ako tatakas?” “How can I escape?”

“Escape what?” Masigasig inquired.

“I’ve been through MERS and SARS,” he said frantically. “It is safer in the Middle East. The scarcity of PPE here would get us killed.”

Our day-to-day work scars our bodies; the illness scars our lungs and claims our lives. So much for the mark of honor and pride.

Exhibit Three

It was monsoon season and there was a blackout in our village. I was three years old; Ma carried me in her right arm as she tried to balance an umbrella in her left. She hailed for a tricycle to take us to the local hospital. The tricycle’s tin roof rattled in the downpour as thunderclaps drowned out my wailing. The faint motor beam barely penetrated through the mist.

Only Ma remembers that night. All I remember are the frequent chills, cough and phlegm. The recurrent hospital visits that stretched through three Christmases and New Years, and the pink linctus Ma would force me to drink every morning. Its nauseating after-smell still crisp in my memory.

In Batangas, whenever Ma had time off from her work as a nurse, she would walk miles to local hospitals and clinics as a Medrep, hauling blue holdalls on both shoulders, under the intense summer sun. She shared information on new drugs in the hope of a sale. During the Christmas and New Year holidays, she would wake up at four o’clock in the morning and walk into town, past the barking of rabid street dogs, to sell fireworks and cakes for extra cash. On fiestas, Ma would join local beauty pageants to win something: If not cash, at least a sack of rice, Ma once said. She always found ways to earn extra money. In case you get sick again, she would say.

Once, I woke up from another bout of whooping cough to find Ma kneeling over her shattered porcelain piggy bank. Paper money spread across the floor like pieces of once carefully folded origami.

Exhibit Four

In July 2020, The Net Gallery, a London-based digital arts platform, uploaded an online exhibition of 15 portraits of “NHS heroes”—their faces painted in confident strokes and bright colors. Their acrylic eyes are either looking at the artist or gazing at a future that is somehow out of reach.

The portraits look otherworldly, as if those healthcare workers in their blue uniforms and tunics got trapped in a busy but sun-filled moment of their days. Perhaps while they were walking along a corridor on the way to a ward call or while they were following the scent of steak bake from the hospital cafeteria.

But my gaze looks for someone more familiar among the portraits. I swipe the screen and the virtual camera pans right. I scan for a portrait of a woman who might look like my mother. Or my sisters, colleagues, or friends. A darker shade of skin, a different texture of hair, a shallower contour of the nose. I cannot find any Filipino nurses in the exhibition.

Shall I comfort myself with the thought that, out of those 15 portraits, at least there are two portraits of men whose skin is a similar shade to ours? Perhaps they (or their ancestors) have embarked on the same journey as my mother, as myself.

There are about 40,000 Filipino nurses in the UK. The current statistics may not even include the Filipino NHS staff who later acquired British citizenship. Why are their faces not illuminated in gold light?

If I were a painter, I would create impasto portraits of Filipino nurses. My steel would dab layers of fire-red paint on the contours of their cheeks, gum their noses dark beige, shade the jaws in carnelian streaks. When my canvas dried, I’d add another layer, in a darker shade: kobicha or coffee-brown, make their eyebrows stubbornly thick. I would finish with a thumb-smudge of dark garnet under their eyes to reflect tiredness: a metaphor for the penumbra of the past, a foreshadow of a bleak future.

Perhaps I am painting the most imperfect portrait of my mother. Perhaps this is how I’ve memorized her, when she comes home, once in two months, from her hospital in Wales, or Stockport, or Norfolk. Which corner of the United Kingdom is my mother in now? How long has it been since lockdown? All I know is that each time she comes home, I see a more exhausted version of her. Even if I use the brightest palette, the days are getting shorter. Even the birdsongs have begun to retract from the window.

Exhibit Five

Sometimes, Ma calls me from the hospital, “Have you seen the news about the Filipino nurse who just died?” Ma’s words escape between moments when she’s chewing cold pasta from Greggs. She is currently on her break. “You’re lucky you’re not in the hospital anymore.” Now, I work in an out-patient clinic helping children and young people who suffer from mental health problems.

Ma is right. I would have been ill by now if I still worked in the hospital. On the other hand, I don’t think as nurses we can ever escape the exhaustion of our work. Whether we are in the rush of Accident & Emergency, the long days of ICU, or the diary-packed tasks of a clinic, a nurse will always come home exhausted. From inadequate staffing and unexpected patient emergencies, to the disruptive and sometimes hostile working environment, there is always something that weighs us down.

But unlike my mother, I am no longer interrupted on my breaks at work. I can eat at lunchtime and go to the toilet when my bladder cannot hold. But most importantly, I am safe from the risk of collapsing or acquiring infections myself. I am safer at a community clinic than in a hospital.

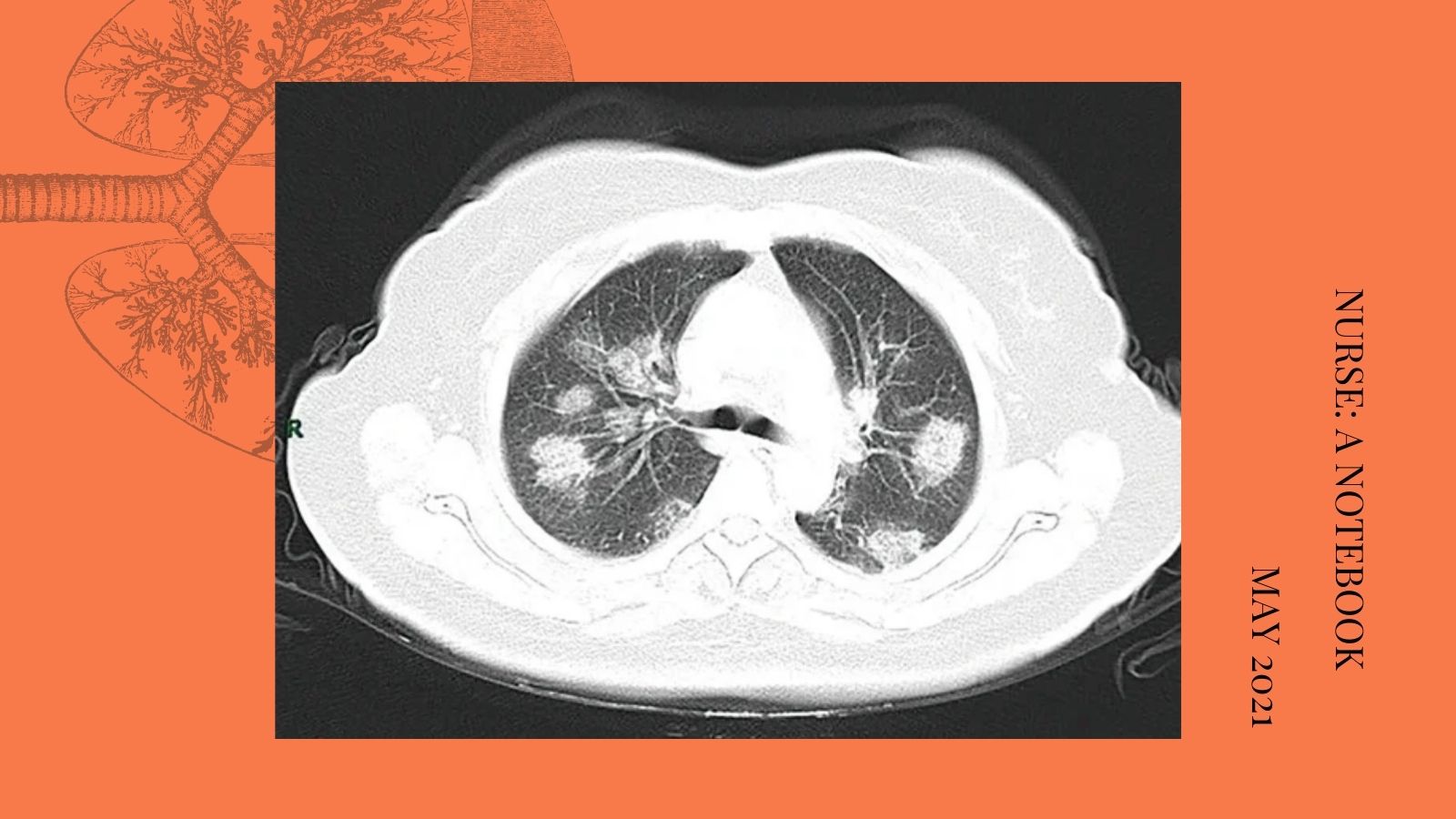

COVID leads to an increase in the risk of developing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a kind of lung scarring after the trauma of the disease. Whenever I think of this, I place a palm on my left breast, thinking of another scar inside my body.

In 2015, three years after qualifying as a nurse, while I was pushing a trolley filled with paraphernalia for my dialysis patients, I collapsed. My knees sucked me to the ground. The thud was so heavy I thought I’d cracked the floor. An MRI scan revealed a fractal-like scar in my left lower lung. Soon, I was diagnosed with bronchiectasis, a progressive, irreversible widening of airways or bronchial dilation in the lungs which leads to a build-up of excess mucus, making me susceptible to pulmonary diseases such as pneumonia or tuberculosis; this could lead to sepsis, a potentially fatal response of the body trying to fight an infection.

I did not know how or why I got that scar until Ma told the doctor that I had primary complex, the most common form of pediatric tuberculosis, when I was young and we still lived in the Philippines. It was monsoon season and there was a blackout in our village. The bedroom walls flickered in lightning; the world around me shook dark blue and violent-white. My lungs were rattling, my breathing was heavy as if there was a concrete block on top of my chest. As the tricycle bounced over potholes, ripping through layers of silver rain, Ma held me close in her arms.

Exhibit Six

I am learning to take these pandemic days as sharp as the sting of a needle in my elbow pit. I press a cotton ball against the prick.

A colleague says, “We will email you about the result.”

From our main hospital site, I rush back into my car and step on the gas to get to the clinic where I now work.

I am not so much thinking about the result of my antibody test, but instead of my colleagues around the country, the rolling news of deaths. I am thinking of my patient Clara, a Sixth Form student who has the shiniest and thickest brunette hair I’ve ever seen which she wears in any way she wants. Ponytail, curled, bunned up. Her Barbie-pretty face that distracts you from private scars.

“It’s a shame,” Clara told me when I last saw her at the clinic two weeks ago. She was fiddling with her red-and-black striped school tie. “It’s a shame our prom is cancelled, but I’ll be okay,” Clara smiled.

Today, Clara has relapsed to cutting her arms with a steak knife.

I step on the gas. The long road is clearer than it has ever been and the expansive sky is a smudge of baby blue.

The antibody test will later show that I am negative. After work, I will chop the claws of the defrosted chicken feet I got from a local Filipino shop. As my knife thuds onto the cutting board and the nails rocket across the worktop, I will remember Ma saying once that chicken feet are extremely rich in collagen, a key protein that plays an important role in wound healing and scar formation. Due to its chemotactic role, collagen is even used in certain dressings to nurse chronic ulcers. During the final stage of wound healing, collagen restructures itself to help close the wound and create a ‘new’ skin.

My knife will clip another claw, and I will also recall that just under the countertop, there are bottles of bleach. I’ll hear Clara’s voice again—scarred with something no one can see: “This lockdown… I’ve thought of drinking bleach,” she disclosed this morning.

Some nights, I come home without cooking or eating anything. Tonight, I throw myself into my bed as mounds of laundry on the floor reek with a pungent scent and the violet shadow of the room rises to drown me.

I think of Clara—how many slashes my fingers will feel down her arm next week. How many superficial cuts I will mentally note while gazing and nodding at her as she narrates her own wounds.

I pour vinegar into the pot of chicken feet, and my Facebook timeline glares bright with another news story: John Alagos, 23, the third healthcare worker and the youngest Filipino-British staff believed to have succumbed to the deadly COVID-19 virus, collapsed and died at home after an exhausting 12-hour shift.

Exhibit Seven

Tonight, Ma calls me on Messenger from Wales, as she walks back to her accommodation after a long day shift. “It was like I was in the oven,” she says.

The Brits are enjoying the August sun in their gardens, but Ma, a woman who is of menopausal age, is finding it harder to breathe in her mask, sweating as if she’s on fire under the paper-plastic-paper layers of her PPE. I think of how the origin of the word scar literally translates as fireplace.

“I really love coming out to this fresh air,” she tells me. The camera jiggles but I can detect a smile on Ma’s face. In Ma, I see a different kind of fire.

Exhibit Eight

The morning I was hit by a bicycle was the last time Ma asked me to do an errand before she left us to work in another country. Realizing she would be gone for years, I wanted Ma to have a delicious meal, so I stepped outside, heading towards Ka Marta’s panciteria, letting the midday sun burn me.

Ma never told anyone she was applying to work abroad, up until the very day when she had to book her plane ticket.

Ma reveals to me, “If I had told people that I was applying to work abroad, they might have told me reasons why I should not leave. They might have asked me: Who would take care of your kids when they get sick? Who would explain to your little girl about menses? You must stay! And I was scared I might believe them.”

Tonight, I am on an online call with her again. “It’s better I stay here in Wales and not go home,” she says. “If I go back, you might catch whatever virus I might be carrying.” As I suck the sour-salt tendons of chicken claws adobo, I realize that our past repeats: a mother leaves her family to take care of others. A mother protects her child from the distance. I’ve lived this story so many times before.

Exhibit Nine

Sometimes I don’t want to listen to the news about healthcare workers dying of COVID. I don’t want to listen to the statements of politicians who cannot even manage this crisis in a first world country. I have no energy. I am exhausted and I just want to nap. But I find myself cursing when I am suddenly woken up, as people step out onto their porches and the English air is scarred with the reverberations of their clapping. I don’t want them to see us as heroes. I want them to see us as humans. We are not just death statistics that keep spiking. I curse.

What does a body feel before it collapses? How much weight does a spirit bear before a knife is snatched out of the drawer and our own loneliness finally cuts deep? There is a scar that I hide underneath my hair. There is a scar hidden in my left lung. And there are scars that, although buried deep within us, continue to burn each waking day to ashes. Every nurse, every patient, every parent, every child in this time of the pandemic, in this era of endless packing and unpacking, when a touch can cure or curse, is tattooed with scars only they know the meaning of.

Tonight, Ma and I are on an online call again as we both cook in separate kitchens. When I look at Ma, I think of her as one massive walking scar. Something that is wrecked and ripped, but also alive. She helps me believe that something endures, after such intense burning.