A manifesto for the post-pandemic reemergence of ‘Old New York’

January 25, 2021

In early 2010, alleged ‘anarchists’ smashed the windows of a newly opened 7-Eleven on St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan, as New York Magazine reported on the convenience store chain’s plan to put local bodegas out of business. Two years later, Starbucks crept too far east into the Village, taking over a much beloved coffee shop and irking many a local who plastered the neighborhood with anti-Starbucks posters and glazed the store’s windows with eggs. That year, the 7-Eleven shut shop but the Starbucks still serves serpentine queues of customers.

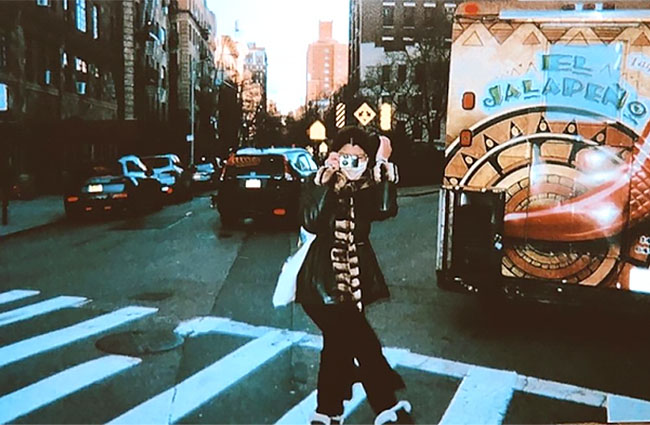

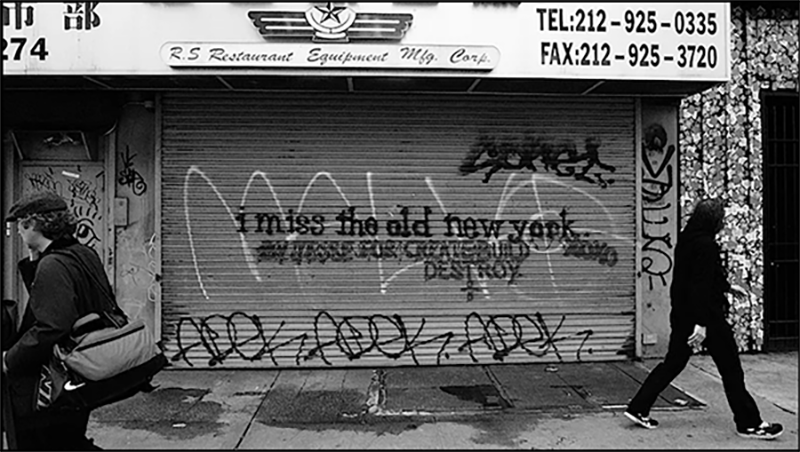

I first moved to New York City in 2017 to study for a degree at Columbia and lived at a friend’s boho-Mediterranean oasis-of-an-apartment in the East Village for the first month. Flaneuring through the Village during this time, I was struck by a signage splattered at multiple locations—in moldy bars and decrepit storefront walls: “I miss the Old New York”.

To an untrained eye, a gaping outsider, the question arose—what makes residents of the greatest city of the world pine for the past? What was ‘Old New York’ and what were its earthly dimensions? And most importantly, what is the problem with the ‘New New York’? It wasn’t until I moved to Morningside Heights — which old-timers still liked to call Harlem — that I began to scratch the surface of this great mystery.

The day I moved into a historic pre-war apartment owned by Columbia University, my old-timer super, who I became great friends with, sat me down in his basement office that doubled up as a guitar studio and carpentry workshop, handed me a mug of tea and told me the story of gentrification. Columbia was the biggest real estate tycoon of this part of the city, and I, therefore, was a gentrifier. Downtown, it was NYU.

There were, but a few genuine representations left of the real Harlem, he told me – illusions, more like.

“And jazz?” I asked.

“Jazz for the tourists, mainly,” he scuffed.

It had been a month since Whole Foods had just opened its first branch in the world’s most historic black neighborhood. They were calling it the final nail in black Harlem’s coffin.

Harlem moved me the way Midtown never could. It dawned on me swiftly, why some New Yorkers pined for an older, more crude, grittier, more ‘real’ time. I was an early convert to the idea too, coming from a bustling, raw, nerve-central metropolis equal in population but bigger and much older.

I’ve been in New York three of my most painful, thrilling, opportune and momentous years. The pandemic has sent the city spritzing from highs to lows and highs.

New York went from becoming the grave of the country to the safest city in America in the summer and back at being orange zoned in the winter. I saw trees turn from bare to lush green to sunset orange and resplendent yellows and then stark bare again, with crystalline droplets of water signaling the first signs of snow. Through this interregnum of the pandemic, undercurrent of change runs through the city.

Paeans have been penned on the death of New York. Crime rates have spiked in 2020, breaking the previous year’s records. Midtown Manhattan, for the most part, remains ghost town. The high-end real estate market is sucked dry. The rich fled the city in droves, and while some might come back, there is no surety of the fact. And while all this was happening, the rest of us who remained, finally got a breather!

Fiscal analysts and real estate watchers are spelling doomsday for the city. The MTA estimates a $16 billion shortfall over the next four years, the largest ever in its history. Between March and October more than 300,000 New Yorkers fled the city. The city is poised to face a $13.2 billion budget crisis over the next four years.

This August, during a fiscal budget meeting over Zoom, Governor Cuomo’s budget director, Robert Mujica, was seen drawing deficit parallels to the 70s. “Today, as a result of the global pandemic, the city’s financial position and the city itself faces perhaps its most severe crisis since 1975. And it may actually be worse than that,” he was quoted saying by NY Mag.

As if more signs were needed, the tallest residential skyscraper in Manhattan – New York by Gehry – reported that more than 200 renters have packed their bags and occupancy fell to 74 percent in September from 98 percent at the end of 2019.

And so, fiscal pessimists have proclaimed that the current crisis isn’t the same as a post 9/11 New York, not even post the global recession of 2008 New York. This New York is doomed for good. While reading multiple declarations of the death of the City, it dawned on me: New York isn’t dying. It is going retrograde.

□ □ □ □ □

Nostalgia, all around the world, appears to reach its peaks during times of especially high levels of immigration or catastrophe, or when the demographic composition of the city is changing most quickly. Canvases of the streets of New York have mutated at a breathtaking speed in the past 50 years. Generations have grown up not being able to draw coherent continuity between the past and the present.

While most go along with the omnipresent changes to urbanscapes, some are not entirely comfortable with the pace or direction of said change. These are the nostalgia-keepers of a city. A very important lot. A city that doesn’t have avowed nostalgia keepers may not be worth preserving in any case.

Old New York is a greatly controversial idea – and one that has been revered and caricatured with equal ferocity. A spate of nostalgia with its own time-space hermeneutics. Being nostalgic for the New York of the 1970s and 80s was common among some patrons of the city.

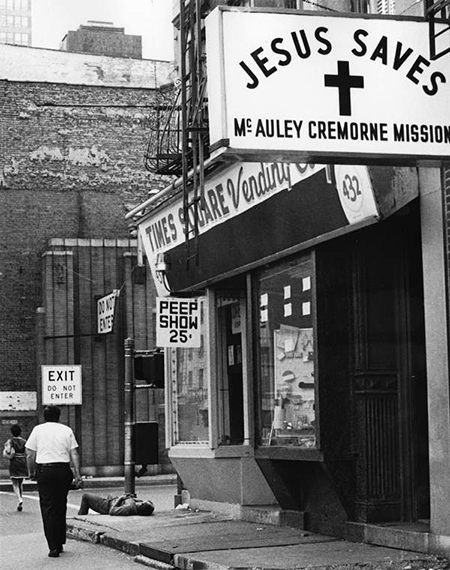

It is, in fact, this grungy, sweaty, feeling, thumping New York of “the people” and the working class, of music on the streets, of high emotions and equally high passions, of pimps, hookers, gangs, porn shops on Broadway – stuff that offends some as well as inspires others — that is embodied by the phrase ‘Old New York.’ If you don’t know Old New York, you are probably living in another city.

What also defines Old New York is the community, the mom-and-pop businesses that were driven out by corporatized, sanitized, airbrushed urbanscapes. A lot of the transformation of New York City into its contemporary version is marred by painful memories of racism, incarceration of black youths, and violence. And yet, in rising inequality and gentrification and lowering neighborly love, nostalgia keepers often pine for Old New York.

As the coronavirus tsunamies through the city in its second round of devastation, revisions and reimagining of the cityscape are needed. And among other changes needed is this: bring back the good of the Old New York!

□ □ □ □ □

Dualisms

Immigration and gentrification have defined and shaped New York forever. Everything — from dollar pizza, to yellow taxis; from the Statue of Liberty to Bronx hip hop — is, in some way, a response to these dualisms.

New York City has historically been a poster child for immigrants – when ICE hounds sniff across the city to detain and deport undocumented immigrants, New York gives them sanctuary and New Yorkers give them shelter – and work.

But it is only in the late 19th century that New York became a global city – when large numbers of poor immigrants from Eastern and South Europe arrived – a major departure from the original Dutch and English settlers that established New York. And even though it took a while for these new immigrants to become ‘white’, there was a marked difference between the second wave of immigration and the third one.

The third wave of the 60s were largely non-white peoples — Asians, Latin Americans, Indians, Africans. This global immigration wave left all binaries shattered – NYC, was, for the first time, neither an all-White or Black city nor was it clearly divided along majority-minority lines. It was becoming the ‘melting pot of the world’.

But the city changed in the past 50 years much more substantially than it did in the first 400. And this is the reason the Spanish Flu of 1920 could not spell as much socio-economic doom to the idea of New York, as COVID is currently predicted to. In the past 50 years, New York became a giant, pioneering cauldron of globalization and neo-liberalism – both of whose future in a post-pandemic world remain highly uncertain and surely volatile.

Immigration changed New York a great deal, but Old New York’s grave was set in stone through gentrification. The story of New York, like the story of many globalized cities in the world today, is the story of gentrification — and counter-gentrification and hyper-gentrification. Another synonym for which is Harlem, and Williamsburg, and Bushwick, among so many other neighborhoods. New York was a true pioneer in shaping and showing what gentrification looks like, and does to urbanscapes.

Take for example, Harlem. In the early 1900s, Harlem was home to upwardly mobile Italians and Jews who had freshly moved from downtown neighborhoods like the East Village, Chinatown and Jewish Town. By doing this, they were leaving behind dense housing conditions in search of better, bigger, more spacious housing.

In the second half of the 19th century, Harlem became the ‘black mecca’ of the city and the country, and went on to symbolize black revolution globally in the 1940s. In this phase, Italians and Jews moved away into the suburbs.

Professor Van Tran is deputy director for CUNY’S The Graduate Center’s Center for Urban Research. As an immigration scholar and urban sociologist, he studies, among other things, immigration, neighborhood gentrification, and urban poverty and social inequality, especially in New York City. After spending his early years in refugee detention camps in Northern Thailand, Tran’s Vietnamese family was settled in the Bronx as a teenager by the International Rescue Committee in 1998.

“In the 60s and 70s, cities in America were in a period of decline. There was a lot of urban decay, specifically crime rates were very high in New York City,” said Tran. Neighborhoods here were not seen as safe. This is when the second and third generation of European immigrants decided they needed to move out further, causing the suburbanization of 1970s, he elaborated. “This is when Harlem became 90 percent Black.”

Once again in the 2000s, Harlem was gentrified. Everyone – from upwardly mobile white professionals but also upwardly mobile minorities moved in. “Anybody with a full-time job and not deep enough pockets to live in hyper-gentrified downtown Manhattan”, said Tran.

Much like Harlem, in other parts of the city too, the concoction of immigration and gentrification had already birthed a spate of nostalgia for the past – and for Old New York.

□ □ □ □ □

Homogenized

The gentrification and homogenization of New York owe a great deal to the universal intermingling of real estate and politics. Back in 1982, Mayor Koch settled the discourse for the future when he said “We’re not catering to the poor anymore … there are four other boroughs they can live in. They don’t have to live in Manhattan.”

Since then, with a few minor exceptions, the trend has climbed upward. A lot of the current global capital flow into the city is attributed to the policies of the Bloomberg era. The uncontrolled advent of foreign real estate investment that folks in the business referred to as ‘vertical safe deposit boxes’ changed New York ruthlessly. That trend continued under De Blasio, even when he acknowledged the existence of, and claimed to fight, growing inequality in the city.

The policy choices that were made under the Bloomberg administration, opened up the city to the rest of the world and to hyper-capitalism. The logic was that the influx of foreign capital would have a trickle-down effect to the poor. We know how trickle-down economics has panned out in the globalization era.

The reality is that the influx of the wealthy elite, both domestic and international, has led to the development of luxury housing in formerly middle-class neighborhoods which, Tran in his work refers to as ‘hyper-gentrification’; distinguishing it from gentrification – the influx of professional middle-class people into hitherto poor neighborhoods.

“The gentrification we’re seeing above 125th Street is the direct result of the hyper-gentrification we’re seeing below 59th Street,” explained Tran. “That’s why the Bloomberg policy era has driven us to where we are today and there, I’m calling the trickle-down effect a hoax.”

The issue of reorganizing the cityscape raised the question of aesthetic – the architectural and spatial dynamics of urbanscapes — and of course, of social and community life.

A lot of the impact of immigration, for instance, is felt at the neighborhood level. Neighborhoods across the city became unrecognizable. Each, a 3D print of another. “Washington Heights and Flushing, which used to be Black and White only, became multiethnic — with Dominicans taking over the former and Chinese and Korean families making the latter home,” said Tran, as an example. Flushing, for instance, was a very middle-class Jewish neighborhood in 1960s and 70s. Today, the signage is predominantly Korean.

Perhaps one of the most immediate and indelible impacts of gentrification is also felt on the visual presentation of the city, which people across the world take to be a measure of their cultural identity.

Homogenization is part and parcel of multinational corporations taking over all over the world. New York is no exception to that. “However, the feeling is intensified in NYC because we are dense and so the visible manifestation is much more in-your-face,” explained Tran.

Another common lament against homogenization is the loss of cultural, artistic and entrepreneurial creativity within the city. The hardcore-punk band Agnostic Front, formed in 1980, who were at the forefront of the burgeoning New York hardcore scene in the mid-1980s, had a famous song, “I Miss the Old New York”:

New York City

The money sucked it dry

Pull the culture from out the streets

It’s all so gentrified

Alphabet city or down on 42nd street

Or the Lower East Side

There was violence in the streets

The greatest city of them all

But it just don’t feel the same

I miss the old New York

For many of those disenfranchised and pining for Old New York, there was an inherent contradiction: was gentrification, the lack of vibrancy, loneliness, and dullness the price to pay for a safer New York?

Between the years 1970 and 2014, homicide rate in New York City decreased by 95 percent Earlier, the city registered 3,500 homicides per year, that’s 10 people being killed every day on the streets. Before the pandemic, it was down to 300. The New New York, was clearly safer.

So, when I first moved here, wide-eyed and all, the corporate listlessness of midtown Manhattan made me swear never to visit that part of town again. And what could be said of the world’s greatest city—a city where being different should be the norm—when some its residents complained that they felt dull, uninspired, distant and most horrifyingly, lonely? A city that is not moving in any particular direction toward greater cultural emancipation and neighborliness, resting rather, at aesthetic complacency and social coldness?

A city that stops soul-searching and questioning the norm is a city that stops growing. Despite all of the cultural diversity accompanying the wave of recent immigrants, New York felt stagnant, unfriendly and homogenized in its most gentrified neighborhoods.

“There is no broad vision of a new and better future,” said Tran, a fellow immigrant. “That edginess and creativity of Old New York moved to other cities, like San Francisco, Austin and Boston.” He feels smaller cities are now carrying the torch for the future. In fact, Jersey City also embodies that edgy quality now; “a time machine to the New York I remember of the Eighties and Nineties,” according to him.

According to Tran’s work, New York City is a Future City Lab – a city that is secretly shaping the future of all world cities; a model and a global leader; grappling with the ever-familiar questions of space, expansion and creating a home for all. So, with the future of globalization in jeopardy, will the ‘New New York’ hold out through and after the pandemic?

Through the pandemic, the number of shootings was said to increase by 112 percent just in November. As for the year, shootings have risen 95 percent in 2020 vis-a-vis the previous year.

As of late November 2020, murders were up by 37 percent over the same period last year —the largest spike in decades. Burglaries rose 42 percent, car thefts 66 percent.

Old New York was drenched in high crime – where people were constantly mugged and fearful of their lives. It left a generation of black American males behind bars because of the differential sentencing that was imposed upon drugs possession.

On the flip-side, with the pernicious growth of inequality, present-day Manhattan boasts of the biggest gap between the rich and the poor in the United States: the richest households made 88 times as much money in 2017 as the poorest 20 percent of families. In fact, rising inequality is such a powerful conversation in New York, Mayor de Blasio runs his campaigns on these grounds.

Just this past year, the Manhattan Institute revealed that the disparity in income between the rich and the poor has remained essentially the same since De Blasio took office in 2014.

And the politics of the city is bound to change too. The pandemic serves as an opportunity to create a different world than the one in which we came into this room. November elections have given New York City a slew of progressive and even socialist elected officials. The New York Times predicts this could be the most progressive New York government ever. Already, the new insurgents have begun to crack the glass ceiling in Albany, with regular run-ins with old guard Democrats.

“There are many of us who saw the crisis of capitalism prior. And there are many of us who are seeing it for the first time,” said 29-year-old newly elected Astoria Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani. Part Indian and part Ugandan, he is one of the first two Indian Americans elected to the State Assembly and was a member of the DSA.

Mamdani said that big changes were coming to Albany, through the actions of newly elected, young Democrats. “Think about it through the lens of democratic socialist candidates that have won, and the fact that we’re going to have a socialist caucus in Albany for the first time in 100 years,” Mamdani said. “There is change in the winds.”

For Mamdani, the promise of post-pandemic change is not just highlighted by the exodus of the wealthy but “the exodus of the working class that happens every day in the city that are being priced out of their neighborhoods.” The former foreclosure prevention counselor called for sure-footed action aimed toward canceling rent, canceling mortgages, having an eviction moratorium and passing a framework for universal rent control. And with the new progressive in charge, “it’s not just a dream put up.”

In 2018, the State Senate showed progressive shifts and in 2020, the real shift has occurred in the assembly’s demographics. “We have a whole host of people coming who’ve been replacing politicians who have been there for 50 years.,” said Mamdani. “It is a time of possibility.”

□ □ □ □ □

Retrograde

Truly, it is only from the rich in Manhattan, and those that could afford the luxury of fleeing and abandoning the city, that one hears the doomsday cries of the death of New York. When one looks beyond Manhattan – things are moving. Even when Times Square was vacant, the neighborhoods across the boroughs were bustling. People are still working and living.

Manhattan has always been the playground for the wealthy and the rich. The rich were able to escape because they could move to a second and third home, they could afford to “travel” and take vacations. Most working-class New Yorkers don’t have the means to do so – they live paycheck-to-paycheck. And so, they stayed. And the city changed, a little.

“In some weird twisted way, I’m thankful that this gives the average New Yorker room to breathe because we’ve been through at least a decade and a half, if not two decades of the astronomical rise of housing prices,” said Tran. The last decade after recession was a turning point in the housing market and the rise has been significant. The pandemic has put a pause on it and made housing more affordable.

The other wonderful thing: New York pre-Covid was “getting out to control” said Tran. “We were so crowded, so dense. The 8.5 million who lived were compounded by the 8.5 million who visited every day. We were a city bursting at the seams and here we are in a moment of calm.”

Prior to the pandemic, the perception was clear and widespread that gentrification was pushing forward, and only certain parts of Manhattan were hyper-gentrifying. Post-Covid, the city is seeing diversification in terms of the frontiers of gentrification, a drawing back of gentrification, according to Tran.

“Manhattan will see a strong scaling back,” said Tran. However, that does not mean gentrification has stopped — it’s simply not being intensified. Residential gentrification will hold stable. Commercial gentrification will be halted. “Once the neighborhood is turned over – like Central Harlem – the forces of gentrification are already there,” explains Tran. “There, the wholesale upgrade of the neighborhood – fancy stores, restaurants, coffee shops – will be slowed.”

The trend of working from home will continue for a while and fundamentally change the future of work, predicts Tran. But the workers will come back, eventually. The companies will be back too. If not the same, new companies will come up.

“New York will be set back five years at least,” said Tran. “New York’s revival and survival is deeply tied to the fate and fortune of the cities and countries around the world. As the world recovers, New York will also recover.”

It is clear that the city appears to be going retrograde. And for some, it is a rather welcome time.

“I think this is an opportunity for the working class who have always been here,” said Tran. Their jobs are not affected by the office hours of midtown. They deliver food and work in the local pharmacy and healthcare– that is the core of New York – and those jobs are not going away, he explained.

“They must reclaim the city, that vibrant neighborhood local feel which was being erased… That is coming back.”