The 2022 cohort of Open City fellows talks about the challenges and triumphs of a year of reporting

December 22, 2022

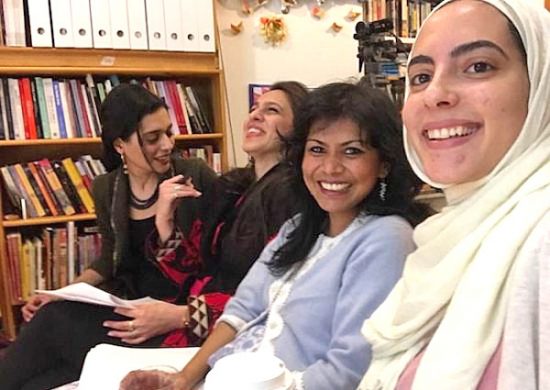

From a story about one of the last major newsstands in the West Village to pieces on the in-between spaces Asian Americans occupy across New York City, the 2022 Open City Fellowship cohort took on a wide range of topics this year. The six fellows—Dhanya Addanki, Asad Dandia, Sana Khan, Grace Jahng Lee, Vina Orden, and Sophia Tareen—hail from a variety of backgrounds but all share at least one passion: a desire to bring an ethical and supportive approach to community-based journalism.

It is clear that they cared deeply about their sources, and rather than shy away from bringing their own histories into their reporting, they used them to enhance it. Along the way, they learned that deep relationships with sources take a lot more time to develop than some so-called traditional journalism requires.

Administered by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, the Open City Fellowship is a unique opportunity for emerging Asian American, Muslim, and Arab writers to publish narrative nonfiction in The Margins on the vibrant East Asian, South and Southeast Asian, Arab and West Asian, and North and East African communities of New York City. Over the course of nine months, the fellows sharpen their editorial skills under the guidance of Noel Pangilinan (AAWW’s senior editor) and Lily Philpott (AAWW’s director of programs and partnerships), attend talks and conversations with publishing and journalism professionals, and help one another develop and workshop their stories.

As their fellowship term was coming to an end, the 2022 Open City Fellows talked about their experiences throughout the year. It is a thoughtful, generous, and informative conversation about power dynamics, working while reporting, and their desires for the future. And there’s even a cameo from one of their moms!

□ □ □ □ □

Could you each speak a little about your own background and how, if at all, it informs what you have done at AAWW?

ASAD DANDIA: I was born and raised in a working-class Muslim community in Brooklyn. I still live there, in my parents’ rent-stabilized apartment that I will probably “inherit.” I am not speaking as an outsider when I write about the communities I write for, and I appreciate that AAWW gave me this platform to tell our stories.

VINA ORDEN: I was twelve going on thirteen when my family immigrated to New York from the Philippines in 1992. A few years later, my father and I stumbled on the AAWW on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. There, I found my home as a reader, for the first time discovering books by Filipinx American writers such as Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters and R. Zamora Linmark’s Rolling the Rs. I’m so happy to see the growth of Asian American and Filipinx American writing in recent years, and especially happy that Workshop OGs like Christina Chiu, Curtis Chin, Luis Francia, Marie Myung-Ok Lee, Ed Lin, Bino Realuyo, Monique Truong, Eileen Tabios, and Barbara Tran continue to write and publish. I still pinch myself that my writing about the Filipinx American community in New York City has appeared in The Margins, that I’m now part of a network of fellowship alums, and that I’ve also gotten to meet and befriend my literary heroes as I’ve grown my relationship with AAWW. For all of this, I’m deeply grateful!

GRACE JAHNG LEE: I’m the biggest Ed Lin fan! I got to take a workshop with him at Giant Robot in L.A. ages ago and was so excited to meet him. And I also attended Kundiman when R. Zamora Linmark was faculty. Writers who have come out of the Workshop are great inspirations to me. I was born stateless in Seoul on a U.S. military base, moved around constantly (I’ve lost count!), and always felt like a foreigner wherever I’ve lived. A sense of place and home are critically important to me, and I’ve always loved reading stories about local communities, especially all the brilliant stories published in Open City.

SANA KHAN: AAWW must have been an incredible teenage sanctuary. In some sense, I think Hyderabad was my sanctuary at that age. I lived in Mumbai and often visited my grandfather, great-grandmother, and other relatives there. It was an escape from challenging experiences, and they had no shortage of romantic tales to spin about days gone by. When I met Mohammed, a Hyderabadi man, in a shop full of stories in New York, it felt like serendipity.

Lily also introduced me to Aaisha Bhuiyan, a former Open City Fellow, and we co-led a workshop on intergenerational creativity. We traced creative genealogies beyond institutions, foregrounding feminized forms of creativity. My mom, who is querying a historical novel set in Hyderabad right now, joined from Mumbai. After having me at twenty-one, she poured her formidable talents into being my biggest advocate. When I was twenty-two, she returned to writing. It was deeply, deeply special that my mama and I could discuss intergenerational creativity in a wider community as part of the workshop.

SOPHIA TAREEN: I am fortunate to have access to a trove of archival content and photos of my family. These images of South Asia contrasted dramatically with my immediate surroundings in Philadelphia and consumed my imagination as a child. As an AAWW fellow, I had hoped to contribute to an archive for future generations and write nuanced stories that may help build solidarity within immigrant communities in the United States.

□ □ □ □ □

Why did you apply for an Open City Fellowship?

VINA: I began pitching and publishing stories about the Filipino American community in New York City to The Margins in 2020. I had been hesitant to apply for the Open City Fellowship since, like most of the other fellows, I had a job and wasn’t sure if I had the capacity to attend the bi-monthly meetings, let alone take the time to research, interview, and write multiple reported stories. However, having downshifted to a part-time job to pivot to a writing and editing career, I was excited about the opportunity to hone my community reporting skills, to meet and learn from mentors Noel Pangilinan and Lily Philpott, guest speakers, as well as the other fellows, and gratefully accepted a spot among the 2022 cohort.

ASAD: I’ve had my eyes on the Open City Fellowship with AAWW since at least 2016, my final year as an undergrad. This was before the Muslim Communities Fellowship was offered by Open City. I applied because I saw it as a wonderful opportunity to be in community with a locally rooted publication that illuminates the stories of the everyday communities making up this city. It’s very hard to break into writing in New York if you’re working-class and/or don’t already have connections in the industry. This fellowship levels out the playing field for people like me. I had to apply!

SOPHIA: I wanted to explore how today’s digital technologies are serving South Asian New Yorkers and how we are serving them. Upon moving to New York, I immediately noticed how technology like tap-and-go turnstiles, city-sponsored high-speed internet, and online access to public services had evolved to play a central role in daily life. I also observed how communities of South Asian New Yorkers took on a different role in the city’s tech scene, many enduring low-wage service jobs. I wanted to find and explore stories about these dynamics.

SANA: Like Asad, I came across AAWW as an undergrad. In class, I was drinking up books like Dictee, Rolling the R’s, Dogeaters, and Native Speaker, and finding The Margins showed me what my essays could look like. As I thought about being a writer, AAWW was a dream that I could only half-breathe into. Some years later, living in New York, I decided to apply. Plus, I had just met Mohammed at Casa Magazines.

DHANYA: I wanted a space to tell the stories of my community with the dignity and respect they deserve. AAWW was a phenomenal opportunity to delve deep into these stories in NYC. I knew that this fellowship would offer me the hands-on editing that I needed with the sensitivity and grace that can only come from communities that have learned from their unique lived experiences. This was a true grassroots, community-based reporting fellowship, and I think the media landscape needs these kinds of stories more than anything else.

GRACE: I attended AAWW’s Page Turner fest over a decade ago when I was visiting NYC from L.A., and it was the most thrilling experience. I’d never met another writer and suddenly, here I was in a room filled with highly accomplished Asian American authors! Almost immediately, I decided to move to NYC to take advantage of the literary resources offered by orgs such as AAWW. I loved the stories published in Open City, its focus on local Asian American immigrant communities in NYC, and was greatly inspired by the work of many previous fellows such as Tanaïs, Sukjong Hong, E. Tammy Kim, and Hannah Bae. I eyed the Open City application for years before getting the courage to apply (my friend Sarah put me in touch with former fellow Cristiana Baik, who took the time to talk to me about her fellowship experience). I wanted to build community with other Asian American writers, develop journalism skills by writing about communities I was invested in, and have a home for the stories I’d cover.

□ □ □ □ □

What topics did you plan to cover during your fellowship? Why these topics?

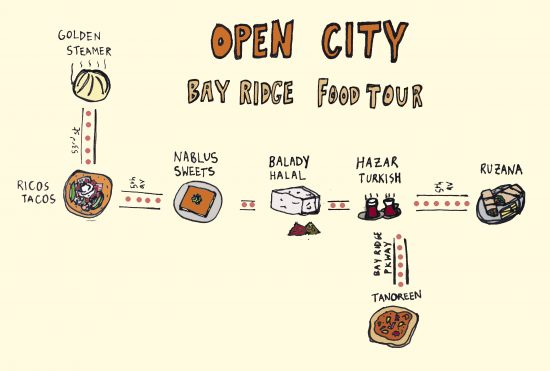

ASAD: I wanted to share the story of a new Muslim community center in Sunset Park, which I believe is central to the religious tapestry of Muslim Brooklyn. This community center has two large prayer rooms, a catering hall that can host three hundred people (you can book the space for just $500), an indoor basketball half-court, and a number of other amenities and services. I was drawn to this story because I’ve witnessed the evolution of some of the people behind it, and I wanted to share that with the AAWW community.

VINA: I planned to work on a portfolio of stories that surfaced underreported stories of the pandemic and its aftermath among low-income, immigrant communities that remain invisible or occupy “in-between” spaces in New York City, which is a bit of a departure from typical Open City stories that focus on specific neighborhoods. Some examples of the “in-between” spaces I wanted to explore were college students and recent graduates facing housing and/or food insecurity, pop-up vendors, and in-home care workers. I didn’t want to only focus on the challenges these communities face, but also on how they empower themselves through mutual aid and advocacy for policy changes.

I also wanted to debunk some myths and misperceptions about the Asian American community, for instance the persistence of the model minority myth, the profits-over-people business paradigm, the scarcity mindset, and the lack of data collection about Asian Americans/disaggregated data on specific groups of Asian Americans, which obscures the needs and policy solutions for our communities.

DHANYA: I wanted to cover Dalit and Dalit-adjacent communities in NYC. This is my community as well, so it was an easy choice for me to delve deeper into the nuances of my own people.

SANA: I wanted to profile Casa Magazines, one of the last remaining newsstands in New York City. One day I overheard Mohammed, the manager, speaking in Hyderabadi Urdu on the phone. Hyderabadi is my ancestral tongue, and I had already spent some years exploring the city’s literature. We began talking, and I was struck by how the store creates an entrepôt of literary activity in the city, a lot like an old Muslim coffee house. It also affords the shopkeepers—two Muslim men—a spontaneity and playfulness that is rare in the United States. Finally, I work in publishing, and hoped to consider some of the overlooked ways that people of color anchor the publishing industry.

GRACE: I had two main topics in mind: mental health and Asian Latinos. I’d lived in Latin America in my teens and early twenties and have a grad degree in Latin American studies. I am fascinated by Asian diasporic communities, as I grew up moving around a lot and found it curious and reassuring that my family was always able to find other Koreans no matter where we lived. I’d previously done research on Korean Brazilians and wanted to expand upon that work, but found that it was much harder to find Asian Latinos in NYC than I anticipated.

SOPHIA: I work in tech, an industry where we increasingly see headlines about the rise of the South Asian American CEO. There are thousands of immigrants from South Asia and other countries, however, who work for tech companies as independent contractors, lack worker protections, and experience wage theft. I wanted to explore these stories (the “in-between” spaces!) that are often excluded from the mainstream narratives of Asian American prosperity in tech.

□ □ □ □ □

Were you able to achieve your goals?

VINA: For the most part, I was able to pursue the themes and stories I set out to cover. I appreciated hearing from guest speakers such as the poet Vincent Toro, who spoke about bringing the Lower East Side of New York City in the 1990s to life on a page, and Jazmine Hughes, who spoke about the different editorial expectations and techniques of being a metro reporter for the New York Times and a long-form culture writer for the New York Times Magazine. Since I don’t have a background in journalism, I think more training during the workshops or from guest speakers in skills like working with data and statistics, writing different kinds of ledes, e.g., anecdotal and scene-setting, would have been helpful.

ASAD: One of my goals in entering the fellowship was learning the process and style of journalistic writing. I come from the background of an organizer and graduate student, both of which offer different skill sets that don’t necessarily prepare one to write journalistic stories. This fellowship was a process towards reaching my goal of doing that better, and I think that process is still unfolding.

SOPHIA: While I feel lucky to have been able to build relationships and write stories with community-based organizations, organizers, and gig workers, I feel like I have only scratched the surface. There are thousands of stories of Asian immigrant communities in New York that are ignored by the mainstream media. It would be my privilege to continue exploring and amplifying these stories.

DHANYA: I achieved one goal that I set: to amplify a specific Dalit community in NYC that isn’t always given the attention it deserves. I immersed myself in this community and was fortunate to make the connections with sources that are necessary for a nuanced story. Beyond the story, I was able to build a more intentional community in general. Even though my other stories did not come to fruition, I am assured that the research and time I put into building out those outlines will lead to a story in the future.

GRACE: Given my previous experiences in ethnography and interviewing, I thought it’d be pretty straightforward to generate the stories. But I found it was more difficult than usual to develop rapport with individuals since most of the interviews were conducted remotely due to the pandemic. Still, I was grateful to find people willing to be interviewed.

SANA: There were days that I went to Central Park and wrote until the grass crosshatched my arms, untangled spiky ethical questions with my cohort, and had long conversations with Mohammed and Ali at Casa Magazines. There were also days that I was precious about my writing to the point of solipsism. When it comes to quantifiable goals, it is easy to come up short. But I do feel fulfilled by what I have learned about myself and my communities. I am especially gratified that I could record the shopkeepers’ stories and situate Casa in Asian American New York City. Dipping into these stories, I am inspired by the vastness of the lives around us.

□ □ □ □ □

Other than reporting and writing stories, were there other high points for you during your fellowship?

VINA: A few events went above and beyond my expectations for the fellowship. We had an opportunity to introduce ourselves and our work to editors at Viking and a literary agent at Ayesha Pande, and I was able to pitch my current book-length project, a YA time-slip novel. Then, in September, Noel and Lily approached me about contributing a written piece for the Against Forgetting notebook.

I also curated a signature event for AAWW featuring readings and performances by writers in the Philippines and the diaspora in remembrance of the fiftieth anniversary of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Sr.’s declaration of martial law and the subsequent reign of terror. I cherished making connections with an international, intergenerational group of writers and artists and was pleasantly surprised by the immediate positive responses to our invitation. I dare say this has been the most important project I’ve worked on in my life thus far.

SOPHIA: The Open City Fellowship is an incredible opportunity to join a community of Asian American changemakers, and I still have so much to learn from this community. I plan to keep engaging through my writing, AAWW events, and community relationships.

DHANYA: I was able to host a historic book event with the workshop for Thenmozhi Soundararajan. I was also able to attend many events that continue to be helpful for my writing career.

SANA: I loved the pitch event, including the chance to prep with the Margins Fellows beforehand. It was fascinating to hear how everyone would translate their concerns into books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Gathering as a collective, thinking and making together, consistently felt generative, true, and exciting. I hope to build on this foundation by continuing to be involved with AAWW in the long term.

ASAD: I could have done more to maximize my fellowship but this was a challenging year for me personally. If anything, I’ve learned that maximizing something means minimizing other things. I wish I had minimized those other things so that I could maximize this fellowship!

GRACE: I really appreciated the opportunity to learn from the other fellows through our meetings as well as through reading and providing collaborative editorial feedback on their work. I’m also grateful for the speaker events that Lily organized for us, like the Viking panel. I really wanted to curate some events and publish many more pieces but as others have said, I think the relationship with AAWW will continue beyond our fellowship year.

□ □ □ □ □

What is your biggest takeaway from the fellowship?

VINA: Building trusting relationships with the communities and individuals you plan to cover is critical work. I had to be creative in identifying interviewees—reaching out to people I knew for recommendations, attending community events, and even putting out a call on social media for my story focused on students and recent graduates. It usually took at least an email interview and an hour-long follow-up video call or in-person interview to get the information I needed to write the story. Then, I made sure to share a draft of the interviewee’s section(s) of the story for review and verification before going to print. In a few instances, I had to go back and excise information or replace a photograph to honor the interviewee’s privacy and security. Taking seriously your ethics and responsibilities as a community member sharing others’ stories for a publication like The Margins was an important lesson I learned.

SOPHIA: My greatest takeaway is that one must be deeply considerate and attentive when telling stories about Asian Americans. There is no single Asian American story; we hail from an enormous range of countries, religions, classes, and circumstances and are the country’s fastest growing minority group. As a fellow, I had many conversations with interviewees, other fellows, guest speakers, editors, and friends about the responsibilities that one carries and does not carry when telling stories. Context matters, and it was important for me to ground myself in my own privileges. When writing about gig workers, I was able to edit and cowrite directly with subjects, a practice that is not conventional in journalism. I am grateful that the AAWW editors not only allowed but encouraged me to pursue this approach.

ASAD: One major takeaway is the need for patience and empathy, especially when you’re working with or interviewing marginalized communities who may be reluctant to speak to journalists. It takes a long time—sometimes months—to build trust with communities.

DHANYA: I agree with Asad, Vina, and Sophia! Working with communities that are hesitant to talk to journalists (for good reasons) is tricky ground. I learned that sometimes it is not my place to tell certain stories, even about my own communities, because of safety risks or general mistrust. My biggest takeaway was to not count the stories that didn’t pan out as a failure, but a way to move forward and create a world where people can safely tell their stories.

SANA: As everyone expressed, our stories were predicated on community. AAWW defines and facilitates community in a way that is not common in media. Noel and Lily prompted us to center mutuality with interviewees, as participants with our own complex backgrounds rather than as detached observers. As a result, we were able to take the time we needed to get to know our sources and craft narratives that did them justice.

GRACE: Yes, many of us are from the same communities that we wrote about, which makes it even more important to consider issues of ethics and privacy.

ROJA: A couple of you mentioned working closely with your sources on the finished project. As Sophia mentioned, this is often a discouraged practice. It brings up the question of who gets let into the process and when. And do you think that it is a journalist’s right to make that decision? For example, if the PR man for a Catholic Church diocese accidentally gives you the (very large) number of people who have reported sexual abuse, do you go back to him to fix it? But when a marginalized worker who is speaking against power says something, do they get the chance to reconsider what they’ve said on the record? Should the power dynamic affect a journalist’s relationship with the source?

ASAD: This is a great question. I think holding yourself to a high ethical standard should be consistent across the board regardless of source, but I know that in practice, the marginalized are often denied these chances at offering corrections. I think the way to equalize the terrain is to allow everyone to have the chance to correct facts and figures.

So let’s go with your example: If the PR agent for the Catholic Church told me that a certain number of people reported sexual abuse, and it turned out that this number was false or inaccurate, I would definitely get that fixed. I don’t think we need to embellish numbers to speak truth to power. The injustice of abuse, whether it was one person abused or a thousand people, would speak for itself. I would just make sure that this grace extends to reportage on marginalized groups as well. I hope this makes sense.

VINA: In terms of my own process, I usually ask to record interviews, which I later transcribe. I do this to ensure I’m accurately quoting my sources but also to refer to if there’s a dispute about what was said. Transparency is key to trusting relationships, and that includes my relationship as a community journalist with the people whose stories I’m shining a light on. Allowing sources to review what I’ve written about them is part of that transparency—I note where I’ve corrected dates and figures that sources have given me off the top of their heads, and I give sources the opportunity to point out factual inaccuracies or misinterpretations on my part. I also give the caveat that I work with an editor on multiple drafts, so what they are seeing may not necessarily be the version that gets published.

In a broader context, journalists and media outlets have a responsibility to check their sources and report as accurately as they can—especially in the age of social media and disinformation and the reading public’s challenges with media literacy. I think a more considerable ethical challenge for the media establishment is the standard of “objectivity” or “fairness” on the one hand and the “larger truth” on the other hand. In a politically polarized climate, it seems reasonable to present “both sides” of an argument. However, there is a danger that, in upholding the standard of “objectivity” or “fairness” over everything else, journalists and editors begin creating false equivalencies or missing the larger story or “truth.”

For instance, if you fear being accused of editorializing or “taking sides” and fail to point out that one side is lying outright, then I think you’re actually doing injustice or harm. I’ve seen Western journalists shudder when they hear Philippine journalist Maria Ressa say, “In a battle for facts, in a battle for truth, journalism is activism.” But what she’s saying isn’t so different from what we in the United States invoke when referring to journalism as the “fourth estate” (after the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government). Journalists aren’t just passive reporters of news and events—they have the agency and responsibility to provide the context and framework for them, and more importantly to hold the most powerful institutions in our society to account.

DHANYA: As a human rights journalist/editor that has recently pivoted to political journalism, the way I operate between groups that have traditional power and those that may not has to be different. When speaking truth to power, as a lot of journalism does, we cannot co-create with those in power. When working with marginalized communities, there is power in co-creating a story together to make sure they are represented with the dignity and respect that is so often missing when covering these kinds of stories.

SOPHIA: I pondered this question during my fellowship and can recall a particular conversation with my dear friends and fellow writers Ria Kalluri and Sagarika Gami on the topic. We discussed how different groups experience reality differently, and so journalists must consider power dynamics when working with sources. In the world of academia, Black feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins writes about the myth of an impartial “view from nowhere” and how social thought “reflects the interests and values of its creators.” This concept is relevant in journalism too—there is a level of objectivity that is unachievable given our personal experiences and ideologies. This is why organizations, like AAWW, that expand the types of voices and perspectives we hear from are so crucial to understanding social conditions and shifting power to historically marginalized communities. I love how Dhanya described the power in co-creation, and I am filled with gratitude to the sources who trusted me and agreed to be actively involved in the writing process.

SANA: Journalists are arbiters of power dynamics. Sources often take cues from you, and it’s up to you what kind of authority you embody. Does your authority come from being allied to those in power? Or from a commitment to integrity? The job of journalists is to quickly contextualize events, and I think this is impossible unless you are able to critically assess the past. There is a difference between understanding history and resolving a story prior to reporting it. I would love to have more settings to mull over the possibilities in journalistic co-creation. I do think that it can take different forms beyond a final sign-off, ranging from oral history to friendship.

As an Indian American, my background shapes my relationship with journalism. The urgent human rights situation in India compels my work, and geopolitical privilege and personal stubbornness let me be impertinent regardless of censorship or retribution. When governments go rogue, writers must embrace their power.

□ □ □ □ □

What’s next after the fellowship?

ASAD: I don’t think I am going to be a full-time journalist. I think journalistic writing will form a part of what I do, but it won’t be the entirety of it. I am too attached to being an educator and organizer. While I love telling stories, I love being a part of stories just as much, if not more so.

VINA: In October, I unfortunately got diagnosed with breast cancer and also learned I was BRCA-1 positive. In the immediate term/the coming year, I’ll be focused on beating and healing from cancer (thankfully, it was caught early and my prognosis remains good). I hope that in this quieter time, I can focus on finishing my YA novel and sending it out to agents in the next year or two. I’ve been reading Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals and take to heart her entreaty for women to transform our “silence into language and action . . . to establish and examine her function in that transformation, and to recognize her role as vital within that transformation.” Given what I know of myself, I will find a way to write about this challenging time and will feel compelled to fight for policies that continue to protect the health (including economic well-being) of women and of patients with cancer and other pre-existing conditions. I hope to return to community reporting (as well as hopefully working with AAWW on more events and public programs) once I’m fully recovered from chemotherapy and surgery—hopefully by summer or fall 2023.

DHANYA: I’m currently a managing editor for a political journalism platform in D.C. and hope to continue co-creating stories with and for marginalized communities.

SANA: I plan on writing more nonfiction, while exploring fiction and comics, as part of the AAWW community. I’m also excited to develop more AAWW workshops with Aaisha next year.

GRACE: I’m trying to finish writing my book and continuing to work as an editor at Hyphen. I hope to publish some additional journalistic pieces. And to learn to write faster! I want to continue to engage with and learn from my cohort and AAWW.

SOPHIA: I hope to continue writing, learning, and creating work that contributes to collective liberation. And of course, I want to stay connected and engaged with the incredible AAWW community.