ياق، توختاڭلار! بۇ بۇغداي سېلىقى توغرىسىدىكى سۆز ئەمەس، مانا بۇ يەردە باشنى يە، دەپتۇ |

“No, stop it! This isn’t talking about a tax on wheat, look, it says bashni ye here, that’s ‘eat your head.’”

March 21, 2023

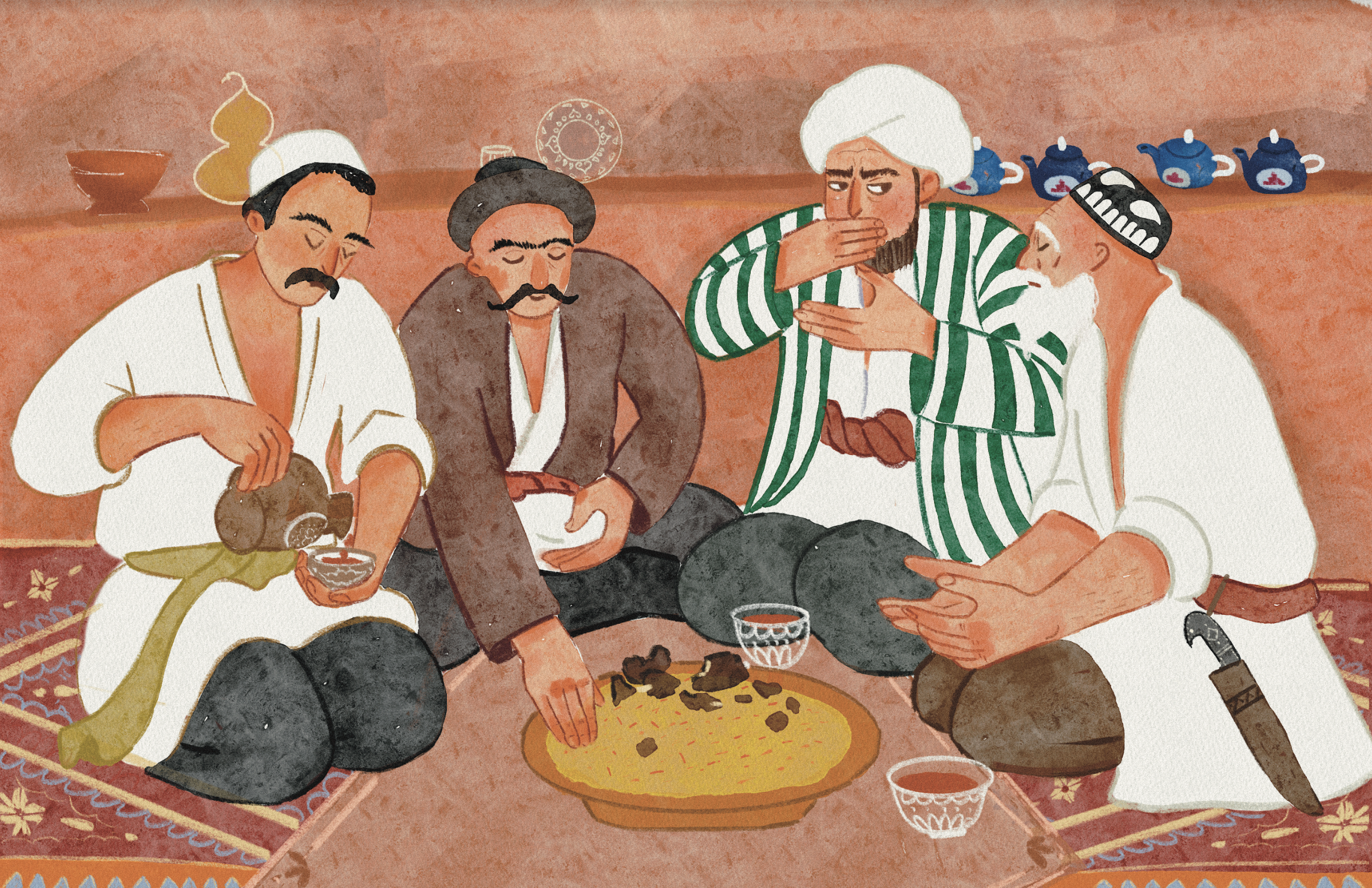

The following short story and its translation are part of the Spring Will Come notebook, with art by Efvan.

پەرمان

بار ئىكەن-دە، يوق ئىكەن، ئاچ ئىكەن-دە، توق ئىكەن. بىزنىڭ يۇرتىمىزدا تۇيۇقسىزلا «باشقان» دېگەن بىر ئىدارە پەيدا بولغانىكەن. ئۇنىڭ باشلىقى ئەخمەق ئىكەن. خەلق بىئارام ئىكەن.

– «باشقان»، بۇ نېمىدېگەن سۆز؟

– مەن نېمە بىلەي، ئۆمرۈمدە بىرىنچى قېتىم ئاڭلىدىم.

– سەن بىلەمسەن؟

– سەنچۇ؟

خەلق تېخى شۇ بىر سۆزنىڭ مەنىسىنى چۈشىنەلمەي ھەيران بولۇپ يۈرسە، بىر كۈنى باشقاننىڭ رەئىسى:

«ھەر بىر كويلۇرىنىڭ چالىشىپ بىردەن بۇيرە ياپىپ باشقا نىيەگە گېلدىرمىشىن بيۇرۇيۇرەم…» دېگەن مەزمۇندا پەرمان يېزىپ دېھقانلارغا چىقىرىپتۇ. لېكىن دېھقانلار ئارىسىدا بۇ پەرماننىڭ مەزمۇنىغا چۈشەنگۈدەك بىرمۇ كىشى تېپىلماستىن نۇرغۇن غۇلغۇلا بوپتۇ.

– بىزچە خەتتەك تۇرىدىغۇ بۇ، سەن نېمىشقا ئوقۇيالمايسەن، ھە؟

– پەقەت چۈشىنەلمىدىم.

– ئېسىت، سىلەرنىڭ مەكتەپتە ئوقىغىنىڭلار! – دېدى بوۋاي، خەتنى ئۈچىنچى ئوقۇغۇچىنىڭ قولىدىن جۇدۇن بىلەن تەرتىۋېلىپ، يەنە بىرسىگە سۇندى.

تۆتىنچى ئوقۇغۇچى:

– ھەر بىر كويلۇ…لەك… لىرىڭ…

– نېمە، نېمە دەيمەن، يەنە كۆڭلەك؟

– نېمە دېسەڭ بولىدىكىن – تاڭ، بىردىن كۆڭلەك دېگەندەك قىلىدىغۇ.

– ھەر بىر… كولەر… لىر… لىرىك… چالىق، لىشىپ، بىردەن، بىر بوير…كورە…

– ئەستاغپۇرۇللا، بۇ نېمە گەپ، زادى نېمە دەيدىغاندۇ؟

– چار ئارىلاشمىغان بىر دادەن بىر كۈرىدىن بۇغداي بېرىسىلەر دېگەنگە ئوخشايدۇ.

توپلىشىۋالغان دېھقانلارنىڭ مېڭىسىدىن تۈتۈن چىقىش كەتتى. يەنە ئاز-تولا ئەرەبچە سۆزنىڭ مەنىسىگە چۈشىنىدىغان بىر كىشى:

– ياق، توختاڭلار! بۇ بۇغداي سېلىقى توغرىسىدىكى سۆز ئەمەس، مانا بۇ يەردە باشنى يە، دەپتۇ.

– توۋا، زادى شۇ باشنى يە دېگەن نېمە دېگەن سۆز.

– باشنى يە، ياق بۇلار يە دېمەيدۇ، يەر دەيدۇ.

ئالاھەزەل قىياس جىق ماجرا بولدى. دېھقانلار بۇ پەرماندىن ھېچنەرسە ئۇقالماي، ئەنسىرەپ ئاخىر شەھەرگە كىرىشتى. شەھەردە خەنزۇچە تىلدا يېزىلغان خەتلەرنى ئوقۇپ چۈشەندۈرگۈدەك ھېلى كىشىلەر ئۇچرىسىمۇ، تېخى بۇ خىلدىكى غەلىتە يېڭى پەرمانلارنى ئوقۇپ بېرىدىغان «مەلۇماتلىق» كىشىلەرنى ئۇچرىتىش ناھايىتى قىيىن بولدى.

دېھقانلارمۇ شۇ پەرمان چىققان باشقاننىڭ ئۆزىگە كېلىپ، قەستەن شۇنداق تىلدا سۆزلەيدىغان كىشى تېپىپ تەرجىمە قىلدۇردىمۇ، يا بولمىسا شەھەردە شۇنداق بىرەر كىشى ئۇچراپ قالدىمۇ، ئۇنىسى بىزگە نامەلۇم، ھەر ھالدا پەرماننىڭ مەزمۇندىن ۋاقىپلانغان بولۇشسا كېرەك. «ھەر بىر دېھقاننىڭ باش ئىدارىگە بىردىن بۆرە تۇتۇپ ئەكېلىپ بېرىشى» بۇيرۇلغانمىش.

دېھقانلار ھېچقاچان مۇنچە سەرگەردان بولۇپ ئازاپ چەكمىگەن بولغىدى. ئەر-خوتۇن ھەممىسى تاغۇ-تاشلارنى كېزىپ مىڭ بىر بالالىقتا بىرنەچچە بۆرىنى تىرىك تۇتۇشتى؛ ئۇلار تاياق-توقماقلار بىلەن قوراللانغان ھالدا قورقۇنچ ۋە دەخشەت ئىچىدە بۇلارنى سۆرەپ يۈرۈپ ئاران دېگەندە باشقانغا ئېلىپ كېلىشتى.

باشقان رەئىسى ئوردىسىنىڭ بۆرىلەر بىلەن تولغانلىقىنى كۆرۈپ ناھايىتى قورقۇپ كەتتى. ئۇ شۇنچە ئېغىر نەپەس ئالاتتىكى، ھەر تىنىقىدا ئىككىلىك ئورۇقلاپ كەتكەندەك بولاتتى. بىردەمدىلا ئۇنىڭ ئۇزۇن ئىنچىكە بوينى ياغاچتەك قېتىپ قالدى. ئاقارغان چاچلىرى ۋە قىسقا قىرقىلغان ئاق بۇرۇتلىرى يېڭنىدەك بولۇپ ھەر تەرەپكە تىك تۇرۇپ كەتتى. دېھقانلار ئۇنىڭ مۇردىدەك قېتىپ قالغان سۆرۈن قىياپىتىگە قاراپ، چوڭقۇر سۈرۈت ئىچىدە جىم تۇرۇشاتتى. بىر ھازادىن كېيىن رەئىس جان كىرىۋاتقان مۇردىدەك كۆزىنى لاپ قىلىپ ئاچتى-دە، جېنىنىڭ بارىچە:

– ئاھ، ۋەھشىلەرنىڭ پالاكىتى!! – دەپ غەزەپ بىلەن ۋارقىرىۋەتتى. ئۇ، بۇ ھادىسىنى باشقان رەئىسىگە بولغان قارشىلىق دەپ چۈشەندى-دە، دېھقانلارغا قاتتىق جازا بېرىشنى بۇيرىدى.

دېھقانلار بىرنەچچە كېچە-كۈندۈز تارتقان ئازاب-ئوقۇبەتلىرى، ئاچ ۋە ھارغىنلىقلىرى ئۈستىگە يەنە بىرقانچىدىن تاياق يەپ، ھاقارەتلىنىپ ئىككىنچى بۆرە تۇتماسلىققا توۋا قىلدۇرۇلدى. ئۇلار بۆرىلىرىنى يەنە دالىغا ئېلىپ چىقىپ، قويۇپ بېرىشكە پەرمان ئېلىپ، ئاران قۇتۇلۇپ چىقىپ كېتىشتى. ئەسلىدە پەرمان: «دېھقانلار تىرىشىپ بىردىن بورا توقۇپ ئېلىپ كەلسۇن» دېگەن مەزمۇندا ئىدى. خاتالىق تەرجىماندىن بولدىمۇ ياكى يۇرتىمىزنىڭ خەلقى ھېچ ئۇقمايدىغان تىلدا پەرمان يازغان كاتىپتىنمۇ، ئىشقىلىپ ئۆتكەن. توغرىسىنى ئېيتقاندا، قەستەن شۇ تىلدا سۆزلەشنى تەشەپپۇس قىلغان رەئىسنىڭ ئۆزىدىن ئۆتكەن. ئۇنىڭ ئۈچۈن مۇنداق سۆزلەرنى ئۇقالمىغان بىچارە دېھقانلارنىڭ شۇنچە جىق ئازاب چەككىنى ۋە جازالانغىنى ناھايىتى ئوسال ئىش بولدى.

1948-يىلى، غۇلجا

“پەرمان” was first published in 1948. The version reprinted here is taken from Zunun Qadiri’s short story collection Chéniqish (Exercise), Xinjiang People’s Publishing House (Shinjang Xelq Neshriyati, 新疆人民出版社), published in 1991.

The Edict

Maybe it was and maybe it wasn’t, it was empty but it might have also been full1This is a traditional opening line for folktales in Central Asia, something like the “Once upon a time” which I inserted at the beginning of the second sentence.. Once upon a time, an office called the bashqan suddenly appeared in our hometown. The official in charge of that office was an idiot. The people were unhappy.

“Bashqan—what does that even mean?”

“How would I know? I’ve never heard the word before in my life.”

“Do you know?”

“What about you?”

While the people were still muddled in uncomprehending surprise at this unfamiliar word, one day the chairman of the office issued an edict to the peasants, which said, “Her bir koyluliring chaliship birden büyre yapip bashqa niyage géldirmishin byuruyurem…”2This sentence is written in late Ottoman Turkish. The author is perhaps referring to the influence of the Pan-Turkic movement of the mid-twentieth century, which might have led enthusiastic local authorities to promote the adoption of Turkish for use in official communication in their region.

But, as no one could be found among the peasants who could understand what this edict meant, considerable commotion ensued.

“It looks like the kind of letter we might write to someone, why can’t you read it, huh?”

“I can’t understand it at all.”

“Pshhh, all that studying at school you all do…” said an old man, ripping the document out of the third student’s hands and offering it to another.

The fourth student: “Her bir koylu… lek…lirin g…”

“Whatever we say is fine, I don’t know, it seems to be saying something about birdin könglek, that means ‘each shirt.’”

“You don’t know, either. Here, you try reading it!” said the old man.

A hunchbacked person who made a living by helping people write letters and submit written complaints started reading: “Her bir koler…lir…lirik. Chaliq, liship, birden, bir boyr, kore…”

“Good grief, what is it? What exactly does it say?”

“It seems to be saying that we have to hand over ten out of every hundred bushels of pure threshed wheat that we produce.”

The peasants gathered there racked their brains. Another person, who knew some Arabic, said, “No, stop it! This isn’t talking about a tax on wheat, look, it says bashni ye here, that’s ‘eat your head.’”

“Oh, come on, what is ‘eat your head’ supposed to mean?”

“‘Eat your head’… no, it doesn’t say ye, it says yer. That means ‘place.’”

There was no little argument about this. Unable to understand anything from the edict, the worried peasants finally went into the city. Although they met a number of people who could read and explain Chinese, it turned out to be very difficult to find any “educated” people who could read this sort of strange new edict.

The peasants came to the bashqan office that had issued this edict. It is unclear to us at this point whether they intentionally found someone at the office who could speak the language the edict was written in and had them translate it, or whether they just happened to meet such a person in the city, but somehow or other they became aware of the edict’s meaning.

What was mandated, apparently, was, “Her bir déhqanning bash idarige birdin böre tutup ekilip bérishi.” In other words, “Every peasant must capture one wolf and bring it to the head office.”

Never before had the peasants suffered the hardship of being vagabonds like this. Men and women alike tramped about the hills and rocks; after a thousand disasters they managed to capture a handful of wolves alive. Armed with sticks and clubs, dragging the wolves in fear and terror, they barely made it to the bashqan.

When he saw his palace full of wolves, the chairman of the bashqan was terrified. He blew out breaths that were so heavy, it was like each one was a weight-loss plan in and of itself. His long, delicate neck stiffened in fear. His graying hair and short-trimmed white mustache stood up vertically in every direction like needles.

Seeing his cold, corpse-like appearance, the peasants fell into a profound silence. A moment or two later, the chairman opened his eyes suddenly, like a corpse come to life, and shouted in a rage, “Ahhhh, what a disaster, you savages!”

Interpreting this incident as an act of resistance against himself, the chairman of the bashqan ordered the peasants to be harshly punished. Thus, on top of the several days of pain and suffering, hunger and exhaustion they had already endured, the peasants were now subjected to a good number of beatings and insults, and were forced to swear that they would never go out and catch wolves again. Receiving an edict to take the wolves back outside and release them, they barely escaped with their lives.

What the first edict had actually said was “Déhqanlar tiriship birdin bora toqup élip kelsun,” or, “Let the peasants strive to weave one reed mat apiece and bring it to the bashqan office.” Whether there was an error in the translation, or whether a mistake was made by the secretary who wrote the edict in this language that none of the peasants had ever encountered before, at any rate an error happened3Comparing this correct translation of the edict with the erroneous one given earlier in the story, the mistake happened in the phrase birdin bora toqup, “weave a reed mat,” which was rendered as birdin böre tutup, “capture one wolf.” As many of Zunun Qadiri’s original readers would have known, in the early twentieth century, a single letter was used to write the sounds o, u, and ö; the letter a was often used for the sound e (though a separate letter for e did exist); and t and q could possibly have been confused for each other if the handwriting was sloppy. It is indeed plausible that, without any context for the purpose of the edict, even a person who understood the language it was written in could have accidentally read böre, meaning “wolf,” for bora, meaning “reed mat,” and tutup, meaning “capture,” for toqup, meaning “weave.”. To tell the truth, though, it was the fault of the chairman who deliberately promoted the use of this language. That was the reason this terrible injustice happened, in which the unfortunate peasants who couldn’t understand such words were made to suffer such hardship and punishment.

This translation came out of the Advanced Uyghur course Michael Fiddler took at the 2022 Central Eurasian Studies Summer Institute (CESSI) at University of Wisconsin-Madison under Akbar Amat.