Tôi phải ở lại trong ngôn ngữ này, như đã trong một cơn mơ bổng, như đã trong một cú kéo chìm, một tự trói buộc, nhọc nhằn và vẫn ở đó, chút lửa nhen. | I have to reside in this language, as in a flying dream, as in a sinking down, a self-bound, burdensome and still there, little fire.

April 19, 2021

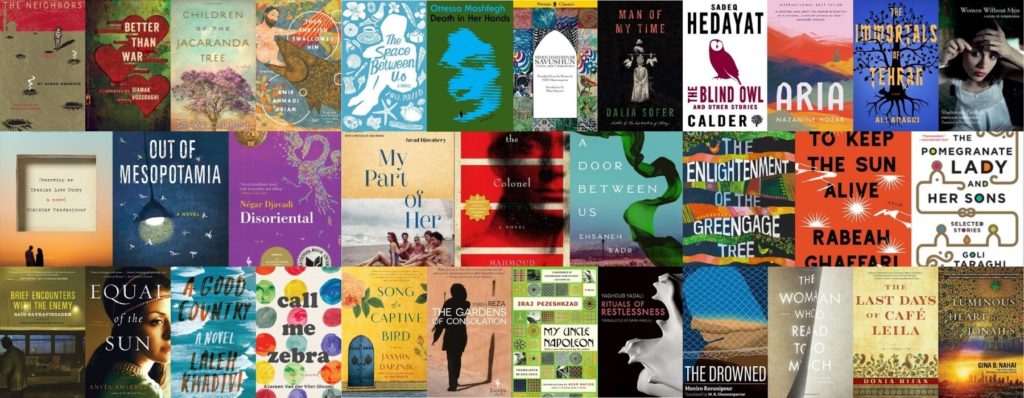

Editor’s note: This essay by Nhã Thuyên opens a notebook of experimental and experiential Vietnamese poetry, the collection of which is gathered here. The pieces of this notebook, having transformed across time and space as well as various material forms, are presented here in their digital bodies as reproductions of the print edition tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) (AJAR, 2021) and its art exhibition in Hanoi. We encourage readers to click on any images of text for enlargement. Print copies of tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) are available for purchase here.

Read the English version of editor Nhã Thuyên’s opening essay here.

Vài ghi chú về tôi viết (tiếng Việt

tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) tượng hình một triển lãm của các sinh thể, vật thể chữ, tạo ra từ sự chơi giữa văn bản và hình ảnh, âm giọng trên nhiều chất liệu và phương tiện, kèm ấn phẩm thơ của những người viết (tiếng Việt) và người trẻ làm nghệ thuật ở Việt Nam.

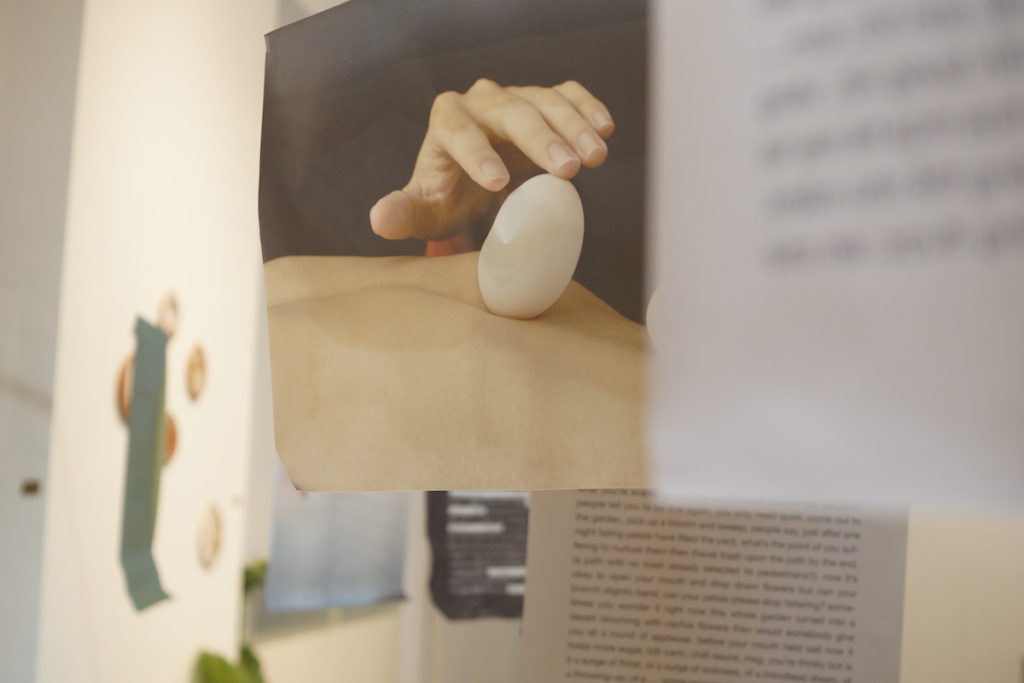

Khi nghĩ về từ, về chữ như một vật thể hay một sinh thể, hiện diện đó liệu có thể là một hữu thực-động đậy hay chỉ là một tưởng tượng thơ? Chữ viết phẳng dẹt trên giấy trên màn hình có thể cọ quậy, hít thở, được tay ta cầm lên, đặt xuống? Chữ, có thể là một thứ gì, không dính chặt với các tiền giả định về nghĩa để tạo nghĩa bằng hiện diện sinh-vật thể? Và cái “đẹp” của các sinh-vật thể chữ bày ra ấy được nhìn thế nào để không bị bó buộc trong cảm giác về tính trang trí của vật liệu?

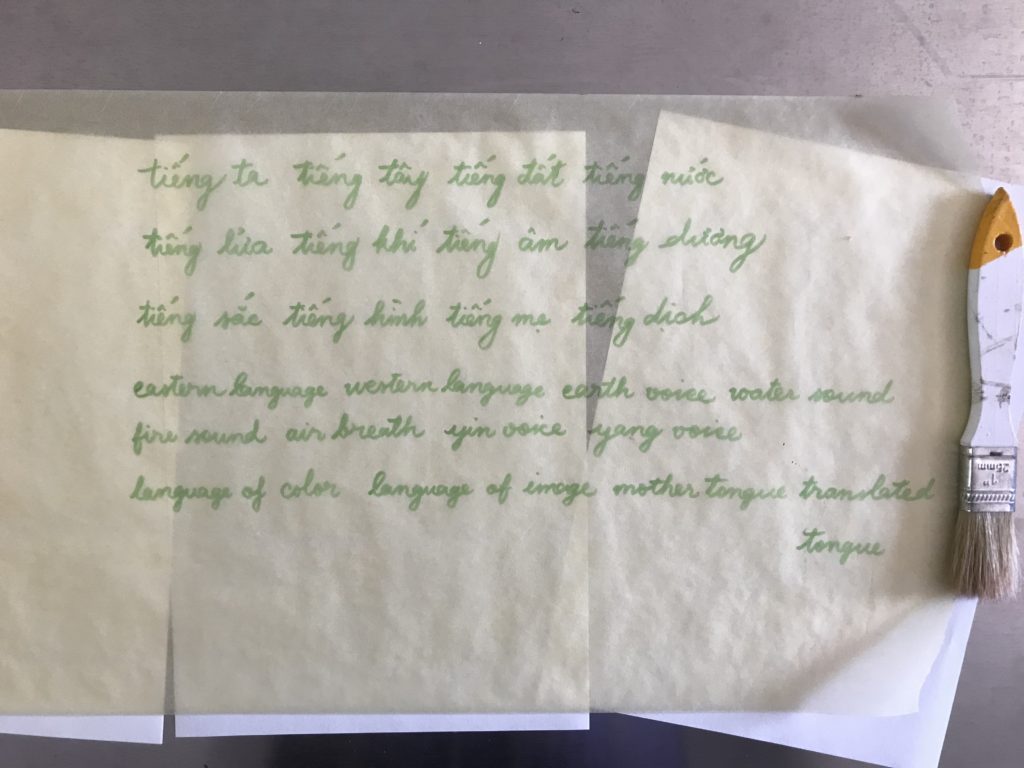

Quá trình làm việc của các tác giả, dịch giả và nghệ sĩ trong dự án này, cốt lõi và xuất phát điểm là hành động viết. Viết chữ và chữ hiện, biến, sinh, hóa, tan, loãng, được, mất; viết chữ dịch thành viết họa, viết hình, viết âm, viết giấy, viết đất, viết nước. Những sinh-vật thể chữ ở đây là quá trình tìm, thử, thử sai, dịch và tự dịch giữa các vật liệu và các phương tiện, để quay lại câu hỏi ban đầu: tôi có thể viết một thứ tiếng (Việt) nào, và thế nào? Câu hỏi này thiết thân đặc biệt với những người viết trẻ, những người viết đã-đang dùng không chỉ tiếng Việt trong đời sống và viết, những người viết tiếng Việt không bắt rễ địa lý, những người viết không có lựa chọn nào ngoài tiếng Việt, những người muốn ăn đời ở kiếp với tiếng Việt… Một câu hỏi về rễ, nguồn. Các dòng chảy vừa chảy vừa xa nguồn. Rễ mọc ngược hút khí. tôi viết (tiếng Việt) tự thân là một lưỡng lự, lưỡng nan, tiến, thoái. Chỉ hành động viết của người viết, như hành động chảy của nước, như hành động tìm chất của rễ, nhẫn nại, tẻ nhạt, miệt mài, chập chững, len lỏi, cuốn trôi.

Tại sao tiếng Việt, và một cái ngoặc?

Cuối năm 2019 đầu năm 2020, tôi phác thảo vài ý tưởng tôi (cùng) đọc thơ tiếng Việt. Tôi đã e dè gửi một lời mời trong những ngày tháng đóng cửa lảm nhảm nói chuyện với tường của mình: tôi sống và viết tiếng Việt (thế) nào? Đây cũng là sự tiếp tục, trong một cách thức lẻ hơn, cụ thể hơn, câu hỏi lúc phác thảo một hình hài AJAR: có một cộng đồng nào của những người viết (tiếng Việt) và cá nhân nương dựa, tham dự trong cộng đồng ấy thế nào? Từ lời mời mở đó, một nhóm nhỏ người trẻ yêu mến chữ nghĩa hình thành. Vừa ấn định ngày gặp tại một thư viện riêng, Hà Nội bùng dịch. Một vài người quyết định không đến, nhưng hầu hết chúng tôi vẫn gặp nhau và ngồi cạnh nhau trong căn phòng nhỏ, rì rầm tập thơ Bến lạ của Đặng Đình Hưng và trong một khoảnh khắc, quên đi khung cảnh bắt đầu trở nên hỗn độn hơn của thành phố. Ba tháng dập dềnh các cuộc gặp on-offline, chủ ý và ngẫu hứng, đứt nối thời gian và xáo trộn không gian, xoay quanh các tác giả, tác phẩm, các chủ đề thơ tiếng Việt, thơ dịch – dịch thơ, người xưa kẻ nay, Đặng Đình Hưng, Phùng Cung, Phạm Công Thiện, Hoàng Cầm, Tô Thùy Yên, Đinh Hùng, Tản Đà, các tác giả AJAR đã xuất bản và của chính những người tham dự mang tới. Mỗi người bày ra một sự đọc, cùng những băn khoăn về đọc và viết, cụ thể hơn, đọc và viết thơ tiếng Việt.

tôi viết (tiếng Việt) nối dài chuỗi thảo luận nhiều cảm hứng đó, và/để đối diện câu chuyện khó và khó san sẻ hơn. Những mặt và mặt nạ dần thân thuộc và thêm đôi ba mặt xa lạ thân thuộc khác nữa, nghe và nói qua màn hình Zoom, lúc mau lúc thưa, lúc hào hứng lúc vô vọng, lúc kéo dài tới khuya, lúc ngắt giữa chừng. Mỗi tuần một câu hỏi được xới lên, viết hay không viết, tiếng mẹ hay tiếng người ngoài, ta hay tây và những từ đó thực sự có ý nghĩa gì, trong và ngoài, (kiếm) sống và viết, chuyên-nghiệp dư, các chủ đề dễ lọt tai bắt mắt, các nhóm phái, các tạp chí, các mô hình xuất bản, quá khứ và hiện tại, tính chính trị của viết… Mỗi người tiếp tục đọc, gợi ý đọc, không nhất thiết các văn chương tiếng Việt, và nhiều hơn là theo mối quan tâm của từng người, bất kể comics hay Đường thi. Những cái tên được nhắc nhỏm, xếp hàng dài trong ký ức đọc: M.Rilke, M.Duras, L.Borges, Charles Olson, Sylvia Plath, Linda Le, Đinh Linh, Phạm Thị Hoài, Dương Nghiễm Mậu và những nhà văn tôi chưa từng nghe đến. Đọc “văn mẫu”, để nhớ và quên, để viết sự đọc, để viết cùng người sống và người khuất, để nghĩ về mình như một người đọc, “đọc dở và đọc nốt” (chữ dùng của Phạm Thị Hoài, một nhà văn viết tiếng Việt xa xứ các bạn thường nhắc), đọc trôi dạt và đọc neo đậu. Những tiếp cận cá nhân về viết giữa các nghệ thuật được đề xuất dưới dạng những thực hành ở thì hiện tại hoàn thành tiếp diễn: những di sản, những thể nghiệm viết đã và đang xảy ra như thế nào và ta có thể viết thế nào từ đây? Làm thế nào để bền bỉ thơ sống thơ, theo nghĩa rộng rãi nhất của từ này, và làm thế nào những ý hướng viết không dễ thỏa mãn thị trường sống sót được? Mỗi người cũng “mò” vào nháp viết và dịch của nhau, chấp nhận nỗi sợ hãi bị nhìn thấy để bàn thảo các chuyện kỹ thuật bếp núc, chuyện viết rồi/để mà xóa, các bài tập về cấu trúc, cách biên tập, việc giữ hay bỏ những bài thơ đầu tay, cả việc viết thơ (thất) tình thế nào. Họ tự nhiên xây dựng các kết nối, cùng làm các dự án riêng chung.

Cấu trúc 12 tuần đọc viết ban đầu thành một sự đi dai dẳng hơn. Nhìn lại bản lưu các giờ đọc viết, dằng dặc các tác giả tác phẩm, các bản thảo đọc dở, các nhật ký ngỏ, tôi ngợp trong năng lượng của những mỏ quặng ẩn lộ kho báu nơi những người viết trẻ còn bẽn lẽn với danh xưng “người viết”. Mong muốn vị kỷ của tôi phần nào hiện thực hóa: tôi nhìn thấy những người đọc, người viết tươi mới, đang ấp ủ các dự định viết, vỡ vạc các thực hành chữ, dù hướng tới viết như một chốn riêng hay một việc, một nghề, một nghiệp. Những cái tên đang ủ nụ và đã nở trong tập sách và triển lãm này mong sẽ dần trở nên thân thuộc với bạn đọc, trong những phấp phỏng đọc viết của riêng họ.

Câu hỏi về cộng đồng trở nên riết róng hơn với riêng tôi sau một chặng đường đủ dài, từ những bước háo hức với sum vầy, kết, tụ, mắt mở, đến những bước chao đảo vì tản mát, chia, lìa, khép cửa. Một cộng đồng không làm sẵn mà luôn phá vỡ và biến đổi. Không có cách nào tuyệt đối không nhọc nhằn cọ xát. Không có cách nào tuyệt đối cô độc, khi còn mơ cái cộng đồng của hai tồn hữu-biểu tượng của Maurice Blanchot: “How not to search that space where, for a time span lasting from dusk to dawn, two beings have no other reason to exist than to expose themselves totally to each other- totally, integrally, absolutely- so that their common solitude may appear not in front of their own eyes but in front of ours, yes, how not to look there and how not to rediscover the negative community, the community of those who have no community?” (Maurice Blanchot, Unavowable Community, bản dịch tiếng Anh của Pierre Joris) [Tạm dịch: Làm thế nào không tìm kiếm không gian đó, khi từ hoàng hôn dùng dắng tới ban mai, hai hữu thể không có lý do tồn tại nào khác ngoài việc phơi trần hoàn toàn trước kẻ khác – hoàn toàn, nguyên khối, tuyệt độ – và nỗi cô độc chung của họ có thể hiện ra không phải ngay trước mắt họ, mà trước mắt ta, phải, làm thế nào không nhìn ra nơi đó và làm thế nào không lần lại cái cộng đồng âm bản trống không này, cái cộng đồng của những người không có cộng đồng?”]

Mỗi cá thể đọc-viết đang trở thành là một cấu trúc khép phải mở ra, lần nữa, lần nữa nữa. Mỗi người viết luôn là một giữa những người viết người đọc khác, những người đã viết và những cuốn sách đã ra đời cùng những người chưa viết và những cuốn sách chưa ra đời. Mỗi cuộc gặp một gương soi. Tôi luôn là tôi số nhiều. Thuộc về và không thuộc về. Mắc kẹt và không tự huyễn

(Nhiều) tôi muốn ở lại trong ngôn ngữ này, trong tiếng Việt, sau những rời rụng, những tàn phá, những hủy hoại, những chia cắt, những kết nối lại. Tôi phải ở lại trong ngôn ngữ này, như đã trong một cơn mơ bổng, như đã trong một cú kéo chìm, một tự trói buộc, nhọc nhằn và vẫn ở đó, chút lửa nhen.

Tháng Hai, 2021

Some notes on tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese)

tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) imagines and constructs an exhibition of word-objects and letter-beings born from a play between texts and images and sounds in various materials and mediums, along with poetic prints of young (Vietnamese) writers and artists in Vietnam.

When thinking of a word, a letter, as an object or a living thing, can this presence possibly be a wriggling being, or does it only exist as a poetic imaginary? Is it possible for letters, lying on the flat surface of a paper or a screen, to jiggle, breathe in and out, be picked up and put down by our hands? Could a letter be something that does not stick tightly with presumptions of its signification, but instead connotes the presence of its object and being? And how can the “beauty” of these exhibited word-objects and letter-beings be seen without being constrained in the decorative effect of the materials?

The core and starting point of the authors, translators, and artists in this project is the writing action. Writing letters: they appear and disappear, are born and transform, melt and dilute, are lost and are found; writing letters translates into writing pictures, writing moving images, writing sounds, writing paper, writing earth, writing water. The word-objects and letter-beings here are a process of searching, experimenting, failing to experiment, translating and self-translating, between different materials and mediums, to come back to the initial question: which (Vietnamese) language could I write in, and how?

This is an intimately significant question to the young writers gathered here: writers who use languages other than Vietnamese in their ordinary and writing lives, writers who write in Vietnamese and are not yet geographically rooted, writers whose only choice is Vietnamese, and writers who want to commit their whole lives to Vietnamese. It is a question of root, of origin. As streams flow away from their origin when forming their existences. As roots absorb nutrients from the air to grow upwards. tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) is by itself a hesitation, a dilemma, a going back and forth. What apparently exists: the act of writing, as the act of water flowing, as the act of roots absorbing nutrients, patient, boring, resilient, tiptoeing, creeping, and floating.

***

Why Vietnamese, and a parenthesis?

By the end of 2019 and the start of 2020, I had sketched some ideas for a workshop series tôi (cùng) đọc thơ tiếng Việt | i (with you) read Vietnamese poetry. I was hesitant to send out an invitation to people whom I didn’t yet know after the months and days I had closed my doors for soliloquy, speaking to my own walls: How could I live and write in Vietnamese, and in which Vietnamese language? The project continues, in a more private and concrete way, the question asked when cherishing an AJAR being: Is there a community of (Vietnamese) writers that each individual can rely on and participate in, and how?

As a response to my open invitation, a small group of young word-loving people formed. Our first meeting was set at a private library during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hanoi. Some decided to stay home, but most still met and sat together in a small room, murmuring the words of Đặng Đình Hưng’s Bến lạ (Unfamiliar Landing) into each other’s ears and for a moment, forgetting the growing chaotic scene of the city. For the next three months, we would hold meetings online and offline, intentionally and improvisationally, un-chronological and spatially mixed up, we worked around the authors, literary works, and subjects of Vietnamese poetry, we discussed translated poetry and the act of translating poetry, writers of the past and the now, poets such as Đặng Đình Hưng, Phùng Cung, Phạm Công Thiện, Hoàng Cầm, Tô Thùy Yên, Đinh Hùng, Tản Đà, as well as AJAR’s new authors, and the writings of the participants. Each participant exposed their personal reading selves, full of wonder for reading and writing, specifically reading Vietnamese poetry and writing poetry in Vietnamese.

***

tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) continues these inspirational reading and writing workshops, and/in order to face a more difficult issue that is more difficult to share. These gradually familiar faces and avatars, and some other familiar strangers met, spoke, and listened to each other through the Zoom screen, frequently exciting and occasionally hopeless, discussions sometimes lasting for many hours, and sometimes being disrupted. Every week, a new question was asked: to write and not, the mother’s tongue and the others’s, east and west and what these words could even mean, inside and outside, writing and (earning a) living, professionalism and amateurism and professional amateurism, catchable subjects of the “contemporary worlds”, literary groups and movements, literary magazines, publishing modes, the past and the now, the personal politics of writing and of the writers, and more. Each continues to read, offering a shared reading list of (not necessarily) Vietnamese literature; while also calling in more personal interests, inviting comics and Tang poetry alike. Many names began to appear in a long queue of reading memories: M.Rilke, M.Duras, L.Borges, Charles Olson, Sylvia Plath, Linda Le, Đinh Linh, Phạm Thị Hoài, Dương Nghiễm Mậu, and many others I had never heard of. Reading “good samples”, to remember and to forget, to write the act of reading, to write with the dead and the living, to think about oneself as a reader, to “read partially and read completely” (“đọc dở và đọc nốt”, a quote from diasporic writer Phạm Thị Hoài), to read adrift and to read anchored.

The participants’ personal approaches to writing in between various art forms suggest a practice in the present perfect continuous tense: what are the ongoing legacies of world literature and literary experiments, and how do we write from here? How can we make poetry live poetically, in the most extended sense of the phrase, and how are the writing intentions which do not easily satisfy the market’s desire able to survive? These young writers also “scoured” each other’s drafts of compositions and translations, accepted the fear of being seen to talk more in depth about techniques, about writing and/in order to erase, exercises to build a writing structure, and practices of editing, what to do with their “first” poems or how to write a broken (hearted) poem. They naturally built their own connections and worked on individual/collaborative projects.

***

The initial structure of a 12 week workshop has since transformed into a more enduring journey. Revisiting the archive of reading and writing folders, the long list of writers and books, the drafts of compositions, some open writing diaries, I become overwhelmed and energized by the ores with hidden treasures in these young writers, who are still reluctant to identify as “writer”. My partly selfish desire has been visualized: I can now see fresh readers and writers in their incubation of writing and reading ideas, who are enthusiastic to plunge into not yet defined practices, though each looks toward writing differently, as a hobby, as a private room for expression, or as a job, a profession, a career. The budding and blossomed voices in this notebook hopefully soon become familiar to our readers, with their swaying paths of reading and writing.

The question of community has become more urgent and heavy to me personally after a long enough journey of AJAR, from the wide-eyed gatherings with open hearts to the wobbling steps of separations with closed doors. It’s never a ready-made and stable community, but communities that are always changing, transforming into others. There is no way to completely not crash into others. There’s no way for absolute solitude. With the persistent dream of Maurice Blanchot’s community of two: “How not to search that space where, for a time span lasting from dusk to dawn, two beings have no other reason to exist than to expose themselves totally to each other—totally, integrally, absolutely—so that their common solitude may appear not in front of their own eyes but in front of ours, yes, how not to look there and how not to rediscover the negative community, the community of those who have no community?” (Maurice Blanchot, Unavowable Community, English translation by Pierre Joris).

Each becoming-personality of reading and writing is a closed structure that needs to open up, once more, once more again. Each writer is a different one among other writers, among their readerships, the ones who write with books already born, and the ones who are not yet writing, with their books still waiting to come to life. Each meeting each mirroring. I am always a plural I. Belonging and unbelonging. Being stuck and not deluding oneself about it.

(Plural) I want to reside in this language, in Vietnamese, after falling apart, after the destructions, the devastated attempts, the separations, the reconnections. I have to reside in this language, as in a flying dream, as in a sinking down, a self-bound, burdensome and still there, a little fire.

February, 2021