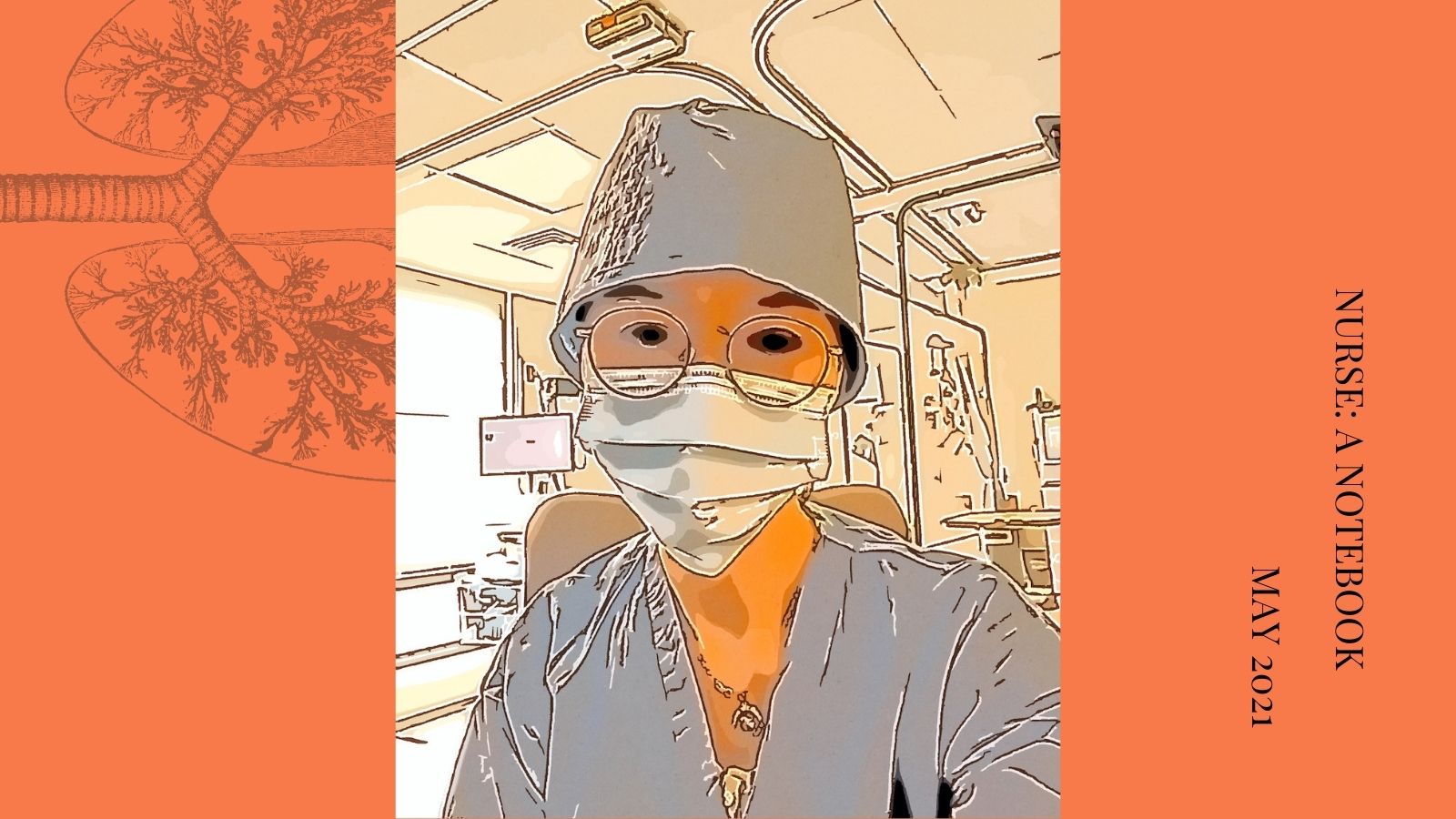

“It feels like you have crossed a river you cannot cross back again”

May 24, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following conversation between Jack Jung and his mother, Susan Jung, was originally conducted in Korean, and has been translated into English by Jack Jung and edited for length. This feature is part of The Margins’ notebook of writing on the theme Nurse. Read other pieces in the collection gathered here.

Son

What I want to talk to you about first is—you were not always a nurse: What was your life like before becoming a nurse? And how did you decide to become a nurse?

Mom

So—so, when I was in elementary school, I always had this vague notion that I will one day become a writer or a journalist. But, your uncle—my elder brother—he was very sickly as a child. He had a bad case of asthma, and he almost died many times. In Korea in the early 1960s, treatment for asthma was not commonly available. The only place at the time that had asthma treatment was Severance Hospital of Yonsei University. Your grandfather took your uncle to Seoul to that hospital.

There was no certainty that the asthma treatment available at the Severance Hospital would work. So, when your grandfather was taking your uncle there, he made us say our final farewells to each other, just in case, because it seemed likely that my brother would never return.

After he got his treatment there—and I assume it must have been steroid treatment—my brother went into anaphylactic shock. My father thought he was dying, so he got him back into the E.R. right away, and the medical staff saved his life. Soon after, asthma treatment became more available in Korea, and your uncle was able to survive and have a life but, because of his condition, our family lived in constant gloom. Always gloomy, and your grandmother was a Christian, and she was always at church. I remember how she prayed in tears for my brother. That is what I saw when I was a child, and that was my life.

Anyways, my brother was constantly going in and out of hospitals, and my parents did everything to take care of him. He was the firstborn son of the family. And I watched, and as I watched I think this vague idea formed in my heart. That I needed to help.

However, by the time I was in middle school and high school, my family lost most of its money. I was trying to decide if I wanted to become a writer or find a job to support my family.

I thought about going into the medical field for the first time, becoming a nurse perhaps, to help others as well. But, by the time when I graduated high school, there was no way for me to afford college, so what I could do was to take the civil service exam to become a civil servant.

I was 18 when I started working as a civil servant, and it was not easy. My first appointment was in the town of Sabuk in 1977, which is a coal mining town, where some years after I left there was the infamous Sabuk Uprising.

When I arrived at Sabuk, it was a dark place. Everything was the color of coal. Now, when I look back on that time, I think it was kind of a divine blessing. That time helped me look at myself at my lowest point. I was so powerless, and my future was shrouded in darkness. I was a junior clerk with an endless workload. I was at the bottom, and I remember thinking, is this all I am capable of?

One day, I think it was a weekend, I was in another city visiting my family (who had moved there), and before getting on a train to return to Sabuk, I went into a bookstore. And it was at that bookstore where I truly discovered books. Suddenly, it was like my eyes opened again. I remember buying so many books that day. I read them rapturously. I think that was the first and the last time that I read so many books so intensely in such a short time. From then on, my childhood and my adolescence, I think, was over, and I was born as who I really am.

Son

What were some of the books that left lasting impressions on you at the time?

Mom

The first writer who left such an impression on me was Saint-Exupéry. His Little Prince was a big shock for me, every single word of it. Then I read his Night Flight and Wind, Sand, and Stars. Of course, I read them all in Korean translations. Later, I started reading books of philosophy, like Erich Fromm’s Escape from Freedom.

Whenever I was sent on a business trip from my office, I would be on trains and buses all day. While waiting for my transportations, I went to a small country café and I read Erich Fromm’s and other books printed in tiny fonts, and every one of those small words pierced my heart.

As I read more and more, I felt I could no longer stay where I was. I wanted to get out and leap toward something else. But my family’s situation was not good and finding an opportunity for something new seemed impossible.

Yet I still wanted to do it. I had to do it. And if I didn’t do it, I thought I was going to go mad. In that state of mind, two years passed (1977-1979), and I was transferred to the city of Wonju from the coal mining town of Sabuk. Once I was in a city, I decided I had to study if I am to live altruistically. I started studying on my own in the evenings. I took a small English class, too. Working and studying like that, it was my small war—my battle against myself.

At the end of all this, after many trials and errors, even though I initially wanted to study medicine, that was out of reach for me financially. If my family’s financial situation was manageable and if I could have had one year more, perhaps I may have studied medicine.

Son

When you say medicine, you mean medical doctor?

Mom

Yes. So, I studied for what I could afford, and that’s why I decided to go to nursing school.

I was in Wonju for two years (1979-1981) while I was studying, but I was also always reading books, and those books were like my compass. I would browse the books and if I could afford it I would buy one. And one of the philosophers I met then that influenced me so much was Dostoyevsky.

Son

In what way?

Mom

Dostoyevsky suffered through all sorts of persecution. And he wrote about things we do in life when life is at its most challenging. I think our ‘codes’ matched in that sense. I also found Kierkegaard during that time.

Son

And you were reading those books while also preparing to apply to nursing school?

Mom

Yes, that’s right. I think in some ways I was very much of an idealist. I think I wanted to choose a path that would allow me to live for others—truly altruistically. I just believed that that was what I had to do. (She laughs) Now that I look back on it, I am amazed by how innocent I was. Anyways, I was accepted into a college in Seoul.

Even though I had hopes to achieve something bigger and build my career as a nurse, and live a life for others, things did not work out that way. I ended up getting married. And after a while, you were born (1988). I closed the book on much of my idealism during that time. I became more focused on my new family, and even more so on my newborn child. And it was during all that that I began to feel like all of it was suffocating. I was still searching for something more. I wanted to find it, and I thought that if I went out into a wider world, then I would be able to.

And so, that was when I began to think about coming to America. This was around 1991-92. But, being married, I couldn’t make such big choices on my own. So, I gave up going to America at the time. Still, life didn’t turn out so easy, and I eventually chose to live on my own (Interviewer’s note: my parents were divorced in 1999).

And as soon as I decided to be my own person, I chose to come to America, and I brought you with me here.

When I arrived on this American land—of course, there were friends and colleagues who had come to the States before me as nurses, and I heard from them about all the hardships they went through, so I hardened myself to be ready for all the difficulties I knew were coming my way when I came here.

What I feared so much when I decided to immigrate was the possibility that I would have to start all the way from the bottom again. To live and work by myself all the way from the bottom again—I was already past 40 when I came to America, I felt small and weak. There was this nameless fear.

But, you know, as they say, “There is nothing stronger in the world than a mother.” And the fact is that I had a child to take care of, and it gave me an almost unconditional, blind courage.

Son

What kind of nursing work did you do when you first arrived?

Mom

Because I had to get permanent residency to be a nurse in the States, what made it possible for me to immigrate here was the legal sponsorships by medical services companies. There are not enough registered nurses in rural areas in the Midwest, so the sponsors would bring foreign immigrant nurses like me to those areas, and we would work there for about two years, or until we got our green card (permanent residency). While I was working as a nurse, I had to pass an English exam to get my green card.

Son

That was an English exam for medical professionals?

(Interviewer’s note: The Michigan English Language Assessment Battery, or MELAB. It was a standardized test used to check English language proficiency for entry-level nursing practice. The test was designed for advanced level users of English as a second language who will need to use English for academic and professional use.)

Mom

Especially for nurses. As far as I know it is not required for doctors. For those nurses who come here on sponsorship contracts, they study to pass the exam in two to four years. But until you pass the test, you must work at the hospital (or for the medical service provider) who is sponsoring you. Contractual obligation and all that. So that is how we ended up in the town Butler.

Son

In Missouri.

Mom

Yes, Butler in the state of Missouri.

Son

That was in 2001.

Mom

Yes, 2001, near autumn or so. And where I first worked was a nursing home there. I was put into the night shift. You were starting seventh grade. And while you slept, I went to work.

Son

Do you have any experiences from that time you want to share?

Mom

Well, around that time, my English needed a lot of work. I could read and write, but I was a beginner in speaking. When I began my night shift at the nursing home, one of the first things that happened, which I can never forget, was when I was making my round to give the patients their prescribed medications. Only RNs (registered nurses) can do this, so that was my job. I knocked on one patient’s door and opened it to give her pills prescribed to her. The patient was an old American lady, and this lady started screaming.

She screamed so loudly and kept screaming. I couldn’t stay in the room, so I left, and an LPN (licensed practical nurse) ran over and calmed the patient down. It turned out that this patient had never seen a person of a different skin color before.

She had gone into a shock at the sight of me. I never went into her room again. So that was my very first experience as a nurse in America. I realized that having a different skin color manifests such things. But I don’t think I was as sensitive in my reaction to what happened then as I would be now. I simply thought then that, “Well, I guess that can happen.” And it was also right after the September 11th attacks, and in that rural town in the Midwest, I accepted it as something that can happen to me.

Son

You were able to deal with it, in a way.

Mom

Yes, at the time, I accepted it. Also, it wasn’t like I could file a complaint to someone in that situation. And I wasn’t about to get into that patient’s face and demand she explain herself.

Son

You worked at the nursing home from 2001 to 2003?

Mom

Yes, from 2001 to June 2003 (She had passed her MELAB exam in June 2002). I decided to come to the East Coast for your education.

I had just gotten info that there might be positions available out here. I interviewed at New Haven, Connecticut. New Haven had those gorgeous gothic architectures of Yale University Campus, and I could see you falling in love with it.

Son

And once in New Haven, you started working at a hospital there?

Mom

Yes, and I worked there for 4 years. (2003-2007)

Son

Throughout my high school years.

Mom

Yes.

Son

How was your experience there?

Mom

The staff there, my coworkers, they really welcomed me, and they were so warm. I think of them like family even now. But it was usually the patients who had a problem with me. There was this one male patient, he was from Maine I think, and at the time I had a hard time understanding his accent, so I asked him to speak again a few times. And the patient was sort of known as a bully among the staff, and he yelled at me saying, “You need to study English more!” So there were things like that. Another time, there was this old white lady. She was fine at first, but as she continued her treatment, her mental condition got worse, and one day she started to use profanity at me when I was treating her. Saying, “Chink! You chink, get out of here!” But at the time, I honestly didn’t know what “chink” meant. I googled it later, and then I learned that it was an ethnic slur.

Son

It sounds like you experienced more discrimination and racism in the East Coast than in the Midwest.

Mom

Yes, I started experiencing more of them. But even then, compared to now, I don’t think the real bad core of it rose above the surface level for most people. It [racism and bigotry] was lurking beneath everyone. Yes, right beneath people’s skin but I don’t think it was coming out in broad daylight just yet. People who still hadn’t lost their minds kept it hidden inside their hearts now that I think back on it.

Son

When I was starting college in Boston, you worked different jobs before starting at a hospital in Boston, right?

Mom

Right, I didn’t know anything about Boston or know anyone here, and I had difficulty finding work. And the way you and I have lived (as Korean immigrants) has been a little different than most, so we didn’t have a connection to Korean American community here or anywhere in the States. We’ve always figured it out on our own.

Son

At the time, rather than staying in New Haven, did you feel that it was more important for us to stay together as family?

Mom

Yes, that is what I thought. And I didn’t think there was any other choice. There’s no other family beside us in this big land after all. And it made sense economically as well for us to live near each other. So I came up here and worked.

Son

Living and working as a nurse here in the States for 20 years now, how has your relationship been with your relatives back in Korea? Were you able to maintain it?

Mom

No…who was it, that Nobel prize winner, Orhan…Pamuk? Is that right?

Son

Yes, Orhan Pamuk.

Mom

Yes, he described it so well in his writings, about what it is like for people who left their country and immigrated somewhere else. How it feels like for them to return to their old homes—those feelings of the distances, the strangeness, and the differences. It feels like you have crossed a river you cannot cross back again. When I read Pamuk’s novels, I empathized with those emotions that he described deeply. And the reason why I couldn’t help but feel that way was because whenever I returned to Korea with you, I felt like I was becoming an ‘other’ to my native country.

And during that time. My older brother—

Son

The one who was sick.

Mom

Yes, the one who was sick. He was suddenly killed in a car accident. After that, all those connections that I had to my home country and family—they broke, or they faded. (Interviewer’s note: my mother’s parents both passed away when she was in college within one year from each other. Her father passed away from illness and her mother was killed in a car accident)

Those feelings have grown into a larger pile inside of me for the last twenty years. This loneliness from being separate from the society over there, and this loneliness from not being fully accepted by the society over here.

Son

You became a veteran nurse in the U.S., and despite being a minority person you now deal with your colleagues and patients very skillfully and naturally. You are a highly skilled nurse at the top of her level. And then, and then, one day, COVID-19 happened. Could you talk about what it was like for you as a nurse to see it happen on the ground level?

Mom

When the pandemic arrived last year, nurses were on the frontlines. Even now. This past year has been very surreal. I still remember very clearly when the pandemic really started here in Boston. The news broke about this big, prominent company having some conference or something and that the virus was beginning to spread from there.

The event had just happened when I was leaving the hospital after my shift. At the hospital, the ambulances never park in front of the main lobby, but I saw a fleet of them there as I was leaving that day, lining up there—the ambulances were carrying everyone from that conference to the hospital and were testing them. That’s when the pandemic really started to hit Boston. The situation continued into March. I was constantly in full pandemic gear while I was working. And everyone worked in those same conditions in the hospital.

And then, the hospital administration sent out an email: that some Asian doctors, when they were leaving hospital late at night, were being harassed by people using slurs and profanities telling them to go back to their country. The administration told us to be careful. And of course, I used to always walk home from hospital, because I love walking. I could not do that anymore.

But when I was still walking home early on during the pandemic, the city streets were completely empty. It was an incredible sight. And I was feeling so many things—I felt like this society had been abandoned.

And at the start, as everyone was dealing with the pandemic, I don’t think I was consciously thinking about myself as a minority and as a person of color. I really couldn’t work and think of those things at the same time.

Nowadays, after I transferred from my old unit to my current one, I treat somewhat more healthy patients. Many of these new patients, I can tell they are very wary of me when they see me. One old patient, in her 70s, who seemed so frail, I tried to help her walk after treatment and supported her arms, but she immediately said, “Don’t touch me! Please!” And I could tell that she didn’t even want to deal with me.

Son

Do you think those kinds of outbursts and interactions from people—did that get worse over the last year?

Mom

Initially, when everything was so frantic at the onset of pandemic, I wasn’t very aware of it, but as soon as things became a bit more manageable—I think Trump really pushed people toward revealing something that was lurking within them. And I started seeing more.

In my previous unit, I was dealing with extremely sick people, so usually there was little interaction between me and the patients. But, once I was dealing with the patients in my current unit who are much more aware and conscious, I can see it in their eyes that they see me differently, that my skin color is not the same as them. A lot of them ask right away without being prompted, “Are you Chinese?”

Son

How do they react when you tell them that you are Korean?

Mom

They just say, “Oh, I see.” And that’s all. When a nurse with fair skin who speaks English without an accent comes to them, they become so comfortable.

Son

Your English is fine, mom.

Mom

These interactions aren’t always the case—but it is how it feels three out 10 times. And of course, you meet amazing patients from time to time.

Son

During the pandemic, has the workload gotten so bad that it really started to push you to your limits?

Mom

Mmhmm. I mean, I don’t look it, but I am strong. And when I can’t cut it with my strength I push through with my spirit, but recently I feel myself getting tired more often. The patients are returning by the droves now as the pandemic seems to be waning, and you can tell that the hospital is leaning on its nurses to deal with this sudden influx of patients. I can feel this happening, and it feels like I am being squeezed, like I am being squeezed to the last drop of my blood.

I know some immigrants who were people with high positions back in their home country. And sometimes they hate being treated in a certain way here. Most immigrants end up having to start all over again from the bottom. And that leads immigrants like me to accept a lot of things, be okay with a lot of things. And I think it was John Adams who said something about first generations having to suffer certain things—so that they can put their roots down in a new place—and perhaps second generations will be able to do something and achieve more. But I had to make the foundation on this new earth—

Son

I think John Adams’ quote is something like…I must learn war and government, so that my child can learn economics, so their child can learn poetry and art…

(Actual quote: I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.)

Mom

Right, something like that.

Son

It looks like your son skipped a few steps there. (Mom gives me a look) (I start laughing nervously) Haha, sorry. Uhm, anyways—

What do you think—beyond the pandemic—what do you think you will want to pursue in the future?

Mom

…well, at some point I will retire. And I think I will want to live for myself.

Son

I will try my best to make that come true.

Mom

(Laughs)

Son

I love that you are still thinking of doing things that you may have had to give up before as you lived this life of helping others. I am grateful.

Mom

Even if I don’t get to live as a writer, I keep reading and I keep thinking about how one is to live as a good person in this world. I want to maintain my sensitivity and stay alert, and I think that is really important to do.

Son

Mom, thank you so much for this interview.

Mom

Thank you so much.

Son

Is there anything you’d like to add?

Mom

Well, I recently read this: when a person flies a plane to reach their destination, they must first reach their highest altitude. Some can reach that height, but many end up running into a countercurrent of air or a storm. They are not able to fly through the path they plotted.

So, they fly lower and lower until they reach a certain point, and that becomes their life—Despite all the effort to reach the height, many people reach somewhere much lower than that. When I read that, I thought, yes, that’s it—when I was young, I was certain I would reach so high and that I would not stay at the bottom. I believed that I would always jump higher for my goal. But now, when I look at where I am, even though I did not fall completely, I have reached a certain middle point. And I think, if I had not tried to reach that height at all, where would I be now? So, this might all be nonsense, but it is important for me to think about.